Parliament House: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The Council House

A

Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Chakshu Roy, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

Chakshu Roy on the 97-year-old building whose corridors and columns stand witness to a vast arc of history – from the time that it was the Council House of British India to when it became Independent India's first Parliament House, from the chaos of argumentative debates that shaped the world's biggest democracy to the consensus marked by loud thumping of desks that shaped many a legislation.

Roughly a century ago, when the foundation stone of the original Parliament House was laid, the building was an afterthought. In the new capital city of Delhi, the focus of finance and attention was the Governor-General’s (President’s) House.

The Council House was built to accommodate a newly created legislature. Legislative institutions have a long history in India. Under the charter given by the British government in 1601, the officers of the East India Company had the power to make laws. A council of the company’s senior officers carried out the corporation’s administration in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. These settlements were independent, each with its committee, and their meeting venue was a room called the Council Chamber in the respective cities.

The company’s fortunes would wane, and in 1833, the British, through law, would strip the company of its trading rights. This law would also separate the executive and law-making functions of the Council and set up one Legislative Council for all British territories in India. Another legal change in 1861 would form a “central though rudimentary” legislative body. The venue for this legislative body’s meetings was the Council Chamber on the first floor of the Government House in Calcutta. The Indian Penal Code of 1860, which defines crime and punishment in the country, was discussed and passed in this Council Chamber. The British constructed another Council Chamber in the viceregal residence in Shimla for the legislative council meetings when the government moved to the hill city in the summers. In 1911, King George V announced that the capital of British India would move to Delhi and laid the foundation stone for a new capital city. The move led to adding a Legislative Council chamber in the government secretariat building in old Delhi.

It also raised a question of whether there would be a separate building for the meetings of the Legislative Council in the new capital city. Till then, the Legislative Council was a unicameral body, and the strength of its membership had risen to 60 in 1909. Its meetings were held in the large council chambers in Calcutta, Shimla and Delhi.

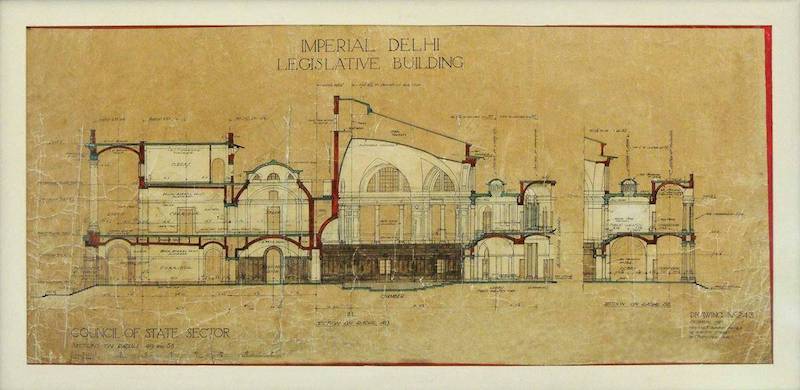

Ideas for New Delhi’s Legislative Council Chamber

During the planning phase of the construction of the new capital city of Delhi, the British had no intention of having a separate building for the Legislative Council. In 1912, a House of Commons MP questioned this move. In his reply, the under-secretary for India, Edwin Montagu, stated that the Legislative Council would meet in a hall in a separate wing of the Governor-General’s official residence. However, Montagu favoured a separate building. Jane Ridley, the great granddaughter of British architect Edwin Lutyens, writes in his biography that both Lutyens and Montagu had urged Lord Hardinge, the first Governor-General of India, for a separate building for the Legislative Council. Hardinge had refused, stating, “No – I, as Governor General with my council, govern India, so it must be in my house!” As a result, in 1913, when Lutyens and Herbert Baker signed on to be the architects for the new capital city of Delhi, their brief only included the design of the ‘Government House (the present President’s House)’ and ‘Two principal blocks of Government of India Secretariats and attached buildings (North and South Block)’. As part of the Government House, they were to design a Legislative Council Chamber, a library and writing room, a public gallery and committee rooms.

Six years later, constitutional reforms recommended by Montagu (and Lord Chelmsford, the Governor-General who succeeded Hardinge) led to the passing of the Government of India Act 1919. This law envisaged a bicameral legislature with a 60-member council of state and an elected legislative assembly with a strength of 140 members. It presented the planners of Delhi with the problem of finding a suitable building where the bicameral legislature could hold its deliberations. The administration in Delhi made two proposals for temporary accommodation for the newly created institution. The first was outlandish, which was to house the legislative assembly in a shamiana (tent). The officers deciding the matter, however, rejected the proposal.

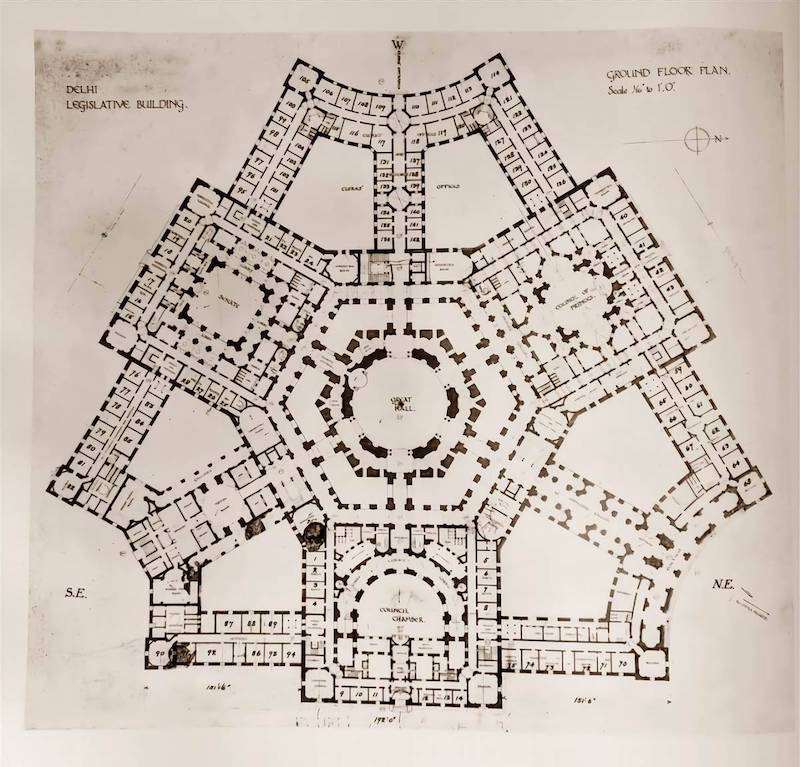

The other suggestion was to refurbish an existing building to house the legislature. The administration accepted this proposal and constructed a larger assembly chamber in the secretariat building in Delhi, and the Legislative Council held its meetings in the nearby Metcalf House. These were temporary arrangements, and Baker was tasked with designing the new Council House. The new building had to accommodate three legislative chambers, the assembly, the council and a council of princes (Narendra Mandal), which a royal proclamation established after the 1919 Act.

The Original Plan

The committee responsible for the construction of the capital city of Delhi decided that the new building would be located at the base of Raisina Hill, below North Block. The plot of land for the new Council House was a triangle in shape. The need to accommodate three chambers and the form of the plot led Baker to design a triangular building. His design showed the three legislative chambers as the three wings of the building connected by a central dome. By this time, the ongoing dispute over the road gradient leading to Government House had deteriorated the relationship between Lutyens and Baker. And, in 1920, when Baker presented his triangular design for the Legislative Council building to the committee, Lutyens bitterly opposed it and wanted a circular structure.

In a letter to his wife, he described the proceedings as: “I gave Baker no trust and the design he put forward did not fit the site… One façade was a dreadful untidy arrangement and his excuse was that he had not worked on it but that it would be all right. I went for him and told the committee that Michelangelo could not make anything of it nor could God himself unless he worked by miracle and against the laws that govern the world.”

Baker submitted a lengthy memorandum to the committee, defending the triangular design. He also suggested an alternative site away from Raisina Hill for the Legislative Council building. He wrote, “The criticism of the previous triangular plan was that its form had been dictated less by the nature of the buildings than by the geometrical limitations of the site. The criticism applies with equal, if not greater, force to the present circular plan… and it is a matter for consideration whether this circular form of building, however beautiful it may be made in itself, will give distinct impression to the sentiment of the national Parliament which India will look for in this building.”

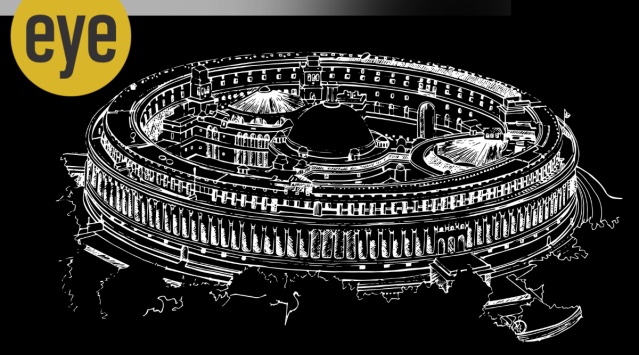

In the end, Lutyens convinced the committee for a complete redesign from a triangular to a circular building. A jubilant Lutyens wrote, “I have got the building where I want it & the shape I want it.” A dejected Baker using a cricketing metaphor told Lutyens that the committee had given him “out” and recast his winged triangular design to fit a circle. The final design had three semi-circular chambers and a big central hall for the library.

The Duke of Connaught, Prince Arthur, laid the foundation stone of the Council House building in 1921, and excavation of its foundation started a year later. The completed building has a diameter of 570 feet. It has a base of red sandstone, which is 22 feet high. On this base stands a colonnade of 144 columns, each 27 feet tall.

The construction required 3,75,000 cubic feet of stone quarried from Dholpur in Rajasthan and brought to Delhi by train. A circular track around the building brought the stone closer to the site. Inside the building, the marble used came from Gaya (Bihar) and Makrana (Rajasthan). The timber is from Assam, Burma and the southern part of the country.

Baker also gave special attention to the acoustics in the legislative chambers. A collaboration between architects, academics, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist and an engineer of Spanish origin brought acoustic clarity to the building. Forty thousand acoustic tiles were imported from the US and attached to the roof of the legislative chambers.

While the Council House was coming up in Delhi, a smaller building was also being constructed in the summer capital, Shimla. It was meant for the Legislative Assembly sessions held in the city in the summer months. The building was inaugurated in 1925 and is now the home of the Himachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly.

The New Circular Building

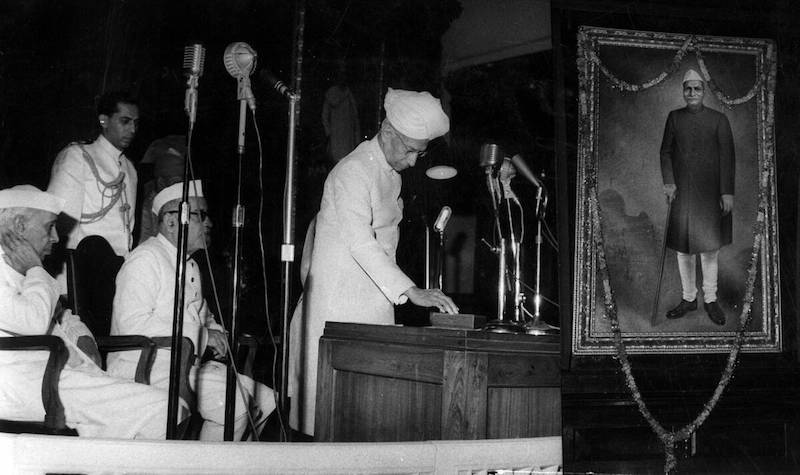

The much larger circular building in Delhi was inaugurated in 1927 by Governor-General Lord Irwin, who read a message from King George V. It stated, “The new capital which has arisen enshrines new institutions and a new life. May it endure to be worthy of a great nation and may in this Council House wisdom and justice find their dwelling place.” Baker presented Irwin with a golden key to open the building door at the inauguration. And the day after the inauguration, the Legislative Assembly started functioning from this building.

The newly constructed Council House would run out of space in less than two years. An attic storey made from plaster (to save money) would be added to the circular building for offices for the growing assembly staff. The animosity that Lutyens had for Baker would raise its head again after the inauguration of New Delhi. Lutyens’ biography mentions that he would take revenge on Baker by manipulating publicity back home.

A young travel writer Robert Byron was hired by two influential British magazines to review the Delhi buildings. Byron, who was neither an architect nor an architectural historian, would severely criticise Baker’s design of the Council House. He described the building as “a Spanish bull-ring, lying like a mill-wheel dropped accidentally on its side”.

New Names for the Old

When India started on the path of Independence, the Council House became a hub of activity. The library in the centre of the building was renamed Constitution Hall. Benches were added to it to accommodate the 300-plus members of the Constituent Assembly, who would draft the country’s Constitution in this domed hall. In the legislative assembly chamber, the members of the Constituent Assembly legislative met to enact laws for a newly independent India.

The birth of a new nation requires space for its institutions. The chamber of princes was converted into a courtroom, and the Federal Court, and afterwards, the Supreme Court, would sit there till 1958. The Federal Public Service Commission, the predecessor to the Union Public Service Commission, also functioned from the circular building for a few years before moving out in 1952.

Independence also meant a change in terminology, and the Council House became Parliament House. There were other changes. After the Constituent Assembly completed its work, the Constitution Hall became Central Hall, a venue for MPs to interact and hammer out differences over tea and coffee. And, in 1954, the presiding officers of the two Houses changed the name of the House of People to Lok Sabha and the Council of State to Rajya Sabha.

Portraits on the Wall

When the Council House was built, its walls were bare as there was hardly any budget for its decoration. The first Speaker of Lok Sabha, Shri GV Mavalankar, appointed a committee to recommend a scheme for the decoration of the building. The committee recommended that the ground floor walls of the building be painted with murals depicting events from the country’s rich cultural heritage.

As part of its discussions, the committee also considered placing the statues of national leaders in the 50 or more niches on the ground and first floors of the Parliament. Following the committee’s report in 1953, work started on the murals. Artists from across the country painted 58 murals showcasing the idea of India from its inception to independence.

Parliament House is also full of portraits and statues of personalities who have shaped the country’s history. In the Lok Sabha chamber, facing the Speaker’s Chair, is the portrait of Vithalbhai Patel, the first Indian presiding officer of the Central Legislative Assembly. Similarly, the Rajya Sabha chamber has one of Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the first chairman of the House. The lobbies of both Houses display the pictures/portraits of the presiding officer of the respective House.

The Central Hall of Parliament also doubles up as a portrait gallery. The first portrait to adorn it was that of Mahatma Gandhi in 1947, and the last in 2019 was that of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee. All the paintings are gifts from individuals or associations who collected money for this purpose. For example, MPs contributed money for the portrait of Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru, painted by the Russian artist Svetoslav Roerich.

There are 50 statutes in the Parliament complex, possibly the maximum outside of a museum in the country. Before 1993, only five statues (Motilal Nehru, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, B R Ambedkar, Lala Lajpat Rai and Sri Aurobindo) were in its precincts. In 1993, during the term of the minority government of Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, Lok Sabha Speaker Shivraj Patil revived the earlier plan of placing statues in Parliament. He announced that a committee of senior parliamentarians had recommended the installation of figures of “the great sons and daughters of India.” The first one to be unveiled in 1993 was that of Mahatma Gandhi. This 16 feet statue of the Mahatma in a meditative pose is the preferred venue of protests by MPs during a parliamentary session. Since then, the statues of leaders from across the political spectrum have been installed in Parliament.

Update, Upgrade

In addition to the artwork and statutes, after Independence, the Parliament building also got a technological upgrade. A new sound system and brighter lighting were the first things to be installed. And, in 1957, the two Houses were equipped with an automatic vote counting machine. Because of the proximity in the seating of MPs in Parliament, the system was designed in such a way that MPs had to use both their hands while voting, the idea being that MPs should not be able to press the voting buttons of their colleagues who might not be present.

Before the new voting machine could be put to use, a problem was highlighted to the Speaker. One of the MPs was differently abled and had only one hand, and the machine required the use of both hands. The solution provided by the Speaker was that an officer of the House would help the MP vote. In this instance, much to the Speaker’s displeasure, rather than wait for the officer’s assistance, fellow legislators helped the MP cast his vote.

The iconic circular building gets the most attention. But it is not the only building in the Parliament complex. After Independence, there was an increase in legislative activity, and the Parliament needed more office space and committee rooms. In response, the Parliament Secretariat started the construction of a new building called the Sansadiya Soudha (Parliament Annexe).

The new building was positioned north of the Parliament House across Talkatora Road. President VV Giri laid the foundation of this building in August 1970. Speaking on the occasion, the Minister for Housing and Urban Development, KK Shah, recalled that Speaker Ganesh Vasudev Mavalankar had first mooted the idea of a new office building in 1952.

Shri Shah said, “His [Shri Mavalankar] was an imaginative plan for three separate buildings on three plots adjoining the Parliament House — one for the Parliamentary Parties/Groups and individual Members, second for the Parliamentary Library and Auditorium, and a third for housing the Committee rooms and their offices and the Secretariat for the two Houses — all of them forming part of the Parliament Estate.”

In his vote of thanks, Speaker GS Dhillon revealed that during the design stage of the Annexe building, there was a plan to build a subway underneath Talkatora Road and connect it to Parliament House. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi approved the proposal. The planners also investigated the feasibility of having a monorail or a mobile walk within the subway. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi inaugurated the Annexe building in 1975. The subway plan never materialised, and MPs had to cross the busy road to access either building. After the 2001 Parliament attack, the section of Talkatora Road that separated the two buildings was included in the grounds of Parliament.

In 1987, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi laid the foundation stone of the next building in the Parliament complex called the Sansadiya Gyanpeeth (Parliament Library). President KR Narayanan inaugurated it in 2002. The Parliament Library, located in the circular building, shifted to a modern purpose-built space in this new building. The original calligraphed copies of the Constitution, kept in airtight nitrogen-filled cases in the circular building, were also moved to a special room inside the library building. When office space in the Annexe ran out, an extension was built, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated it in 2017.

Signs of Age

The Parliament building is now in its 97th year and has started showing visible signs of age and neglect. For many years, there were unplanned changes to the structure. Empty spaces were converted into offices, claimed for storage or became dumping grounds for unrequired material. The condition was much worse on the upper floor of the building, away from the public eye. Former Secretary General of Rajya Sabha, Vivek Agnihotri, said he was “dumb-struck by the conditions in which several lower-level officers and staff members were accommodated on the second floor of the main building.” He stated, “The total ambience looked somewhat vandalised on account of various ad hoc additions and so-called improvements made to the structure within.”

Lack of proper maintenance has also contributed to the distress in the building. In its 1986 report, a Parliamentary committee was scathing in its criticism of the Central Public Works Department, which is responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of the heritage structure. The committee observed, “In a period of less than 60 years, which is a short span in the life of a historical and prestigious building of the stature of Parliament House, the edifice has developed ugly scars when viewed minutely. Though the imposing massive structure still looks very sturdy from outside, it has been shaken to its very foundation by the inexplicable and inexcusable neglect, apathy and carelessness shown by the CPWD in its proper and much needed maintenance.” The committee then went out to detail serious issues related to the building.

But what was known only to insiders started coming out in the open after a series of mishaps. In June of 2009, a part of the ceiling of the ground floor office of Petroleum Minister Murli Deora collapsed. Storing LPG cylinders for the canteen on the floor above the office caused the incident. This newspaper reported that the Deputy Chairman of Rajya Sabha observed, “It is a matter of grave concern and carelessness that in the Parliament House, a heritage building, this kind of incident was allowed to happen.” He went on to state, “Similarly, the damage of the structure due to water seepage is also a serious issue, and if immediate action to shift the canteen and wash area is not taken, it may have serious implications, including the safety of the occupants in the offices on the ground floor.”

Over the years, there have also been minor incidents of fire and multiple incidents of foul smell due to blocked sewer lines and air conditioning ducts. More recently, in 2012, the proceedings of the Rajya Sabha were interrupted for half an hour due to a stench in the House. These incidents led to Meira Kumar, the then Lok Sabha speaker, stating that the parliament building was “weeping”. The next Speaker, Sumitra Mahajan, echoed similar views when she wrote to the Urban Development Ministry that the iconic circular building showed “signs of distress”.

The roughly 100-year-old Parliament House is now ready to pass the baton to its newer counterpart next door. This time, things are a little different. The new Parliament is the cynosure of all eyes and the focus of the Central Vista redevelopment. Hopefully, it will continue to be a forum for passionate debate for the next hundred years.

B

May 29, 2023: The Indian Express

The parliament building’s construction took six years – from 1921 to 1927. It was originally called the Council House and housed the Imperial Legislative Council, the legislature of British India.

But the partnership between the architects wasn’t all smooth sailing. If one stands at Vijay Chowk at the centre of Kartavya Path, one end of the road leads to India Gate and the other end seems to be going towards Rashtrapati Bhawan.

However, the President’s house is flanked by two other buildings, the North Block and the South Block that house major government offices. The elevation of the road obscured the Bhawan from the view of those present there. As Lutyens designed the Bhawan, this positioning became a source of conflict between the two men.

How did the old parliament building’s construction take place?

In 1919, Lutyens and Baker settled on a blueprint for the Council House. They decided on a circular shape as the duo felt it would be reminiscent of the Colosseum, the Roman historical monument.

It is popularly believed that the circular shape of the Chausath Yogini temple at Mitawli village in Madhya Pradesh’s Morena provided inspiration for the Council House design, but there is no historical evidence to back this up.

Lutyens, in particular, was not in favour of adding hallmarks of Indian architectural traditions in his works, believing them to be inferior in quality. As The Indian Express reported, “Soon after he arrived in India in March 1912, he wrote to his wife, ‘I do not believe there is any real Indian architecture or any great tradition. There are just spurts by various mushroom dynasties with as much intellect as there is in any other art nouveau.’” On the other hand, Baker thought that the goal of ultimately projecting the strength of British imperialism and rule over India could also be achieved by mixing Eastern and Western styles. However, he did agree with Lutyens on the superiority of European classicism, upon which he said that Indian traditions had to be based.

In the book An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain’s Raj by Thomas R Metcalf, he wrote: “In a letter to Baker, still in South Africa, he [Lutyens] described, facetiously, how one would erect buildings in the two chief Indian styles. If a ‘Hindu’ structure were required, he wrote, ‘set square stones and build childwise, but, before you erect, carve every stone differently and independently, with lace patterns and terrifying shape…’ If the choice were ‘Moghul,’ he continued, build ‘a vasty mass of rough concrete, elephant-wise, on a very simple rectangular-cum-octagon plan, dome in anyhow, cutting off square… Then on top of the mass put three turnips in concrete and overlay with stone or marble as before…”

A few Indian elements, such as jaalis (a latticed carving depicting objects like flowers and other patterns) and chhatris (a domed roof atop a pavilion-like structure) were finally added.

What was the material used?

According to the official Central Vista website, around 2,500 stonecutters and masons were employed just to shape the stones and marbles required for the construction of the building.

The circular building has 144 cream sandstone pillars, each measuring 27 feet. The total cost of construction then was Rs 83 lakhs. Indian workers constructed the Parliament.

On January 18, 1927, Sir Bhupendra Nath Mitra, a member of the Governor-General’s Executive Council and in charge of the Department of Industries and Labour, invited Viceroy Lord Irwin to inaugurate the building. The next day, the third session of the Central Legislative Assembly was held there.

With the British regime in India coming to an end, the Constituent Assembly took over the building and in 1950 it became the location of the Indian Parliament as the Constitution came into force.

What will happen to the old parliament building now?

The building will not be demolished and will be converted into a ‘Museum of Democracy’ after the new Parliament House becomes operational.

The old, pre-2023 Parliament House

Liz Mathew’s memories through history

Liz Mathew, May 28, 2023: The Indian Express

Yesterday as the Monsoon Session concluded, a sombre mood dawned on me as I walked out of Parliament House. If the powers that be are to be believed, this session – as stormy as several others in the recent past — will be the last to be held in this magnificent building, built 100 years ago. The Winter Session in November-December is expected to be held in the new building, which is coming up at a rapid rate, and fast overshadowing the majestic structure designed by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker. But nothing can erase the history created in this building.

I began my career in journalism in Delhi, literally growing up professionally in this building. Like the 144 pillars in this marvellous piece of architecture, I too witnessed the major political events of the last 25 years in its confines. (The only big event I missed was the 2001 terror attack which happened when I was out of Delhi.)

As I walked out of the building, I was filled with mixed feelings about the new building. Many share my sentiments. The question that is weighing heavily on everyone’s mind is: Will the atmosphere of the Central Hall, the focal point of many a churning in national politics, be replicated in the new building? Some say that in its place there could be a frugal lounge that could deprive members, their immediate families, senior politicians, including chief ministers who visit Delhi, and senior journalists of the convivial atmosphere that was the signature of the Central Hall.

The BJP in its current avatar does not seem to have an emotional connection with the Central Hall — senior cabinet members rarely visit it. In the past, even prime ministers used to spend time there. This change in political culture, exacerbated by the pandemic and its restrictions, has diminished the ethos and activities of Parliament: The duration of sessions has reduced, and the fourth estate has become almost invisible. The Central Hall is a “no entry zone” not just for journalists but for former MPs as well. Senior journalists now get nostalgic about spending hours with politicians, often sipping hot coffee or soup in the Central Hall, where the fans are installed upside down.

I came to Delhi when national politics was undergoing a churning of sorts. The aristocratic politician was giving way to the leader from the grass roots. Speeches in clipped English were being replaced with oratory in Hindi dialects from mofussil centres. But Parliament still brimmed with warmth and camaraderie. The veterans had accepted the leaders emerging from Mandal and Mandir politics.

Despite the intense schisms, one could see members from both sides having a friendly chat over snacks from the Coffee Board-run outlet. At least four ideologies were in full play — the Congress trying to retain its foothold, the socialists raising Mandal politics, the Left still steady under a credible leadership and the BJP. This social space shared by different ideologies was later used by Atal Bihari Vajpayee to stitch a rainbow coalition.

As I watched regimes change – from Vajpayee’s 13-day ministry to the uncertain United Front days of H D Deve Gowda and I K Gujral and the relatively stable but eventful decade with Manmohan Singh at the helm of affairs — my experiences at Parliament House also underwent transformations. We used to carry bundles of papers – answers to MPs’ questions, panel reports. Now, a paperless Parliament is becoming a reality.

What I miss the most is the absence of quality debates. I have seen and heard Vajpayee, L K Advani, Madhav Rao Scindia, Rajesh Pilot, Chandrashekhar, Somnath Chatterjee, Indrajit Gupta, S Jaipal Reddy, George Fernandes, Sitaram Yechury… the list is long. The success and the productivity of a Session used to be measured through the quality of debates, not just the hours spent on the bench or bills passed. I could get a sense of the nuances of Indian politics by listening to politicians like Pramod Mahajan, K Karunakaran, Arjun Singh, Pranab Mukherjee and Arun Jaitley. Even the transformation of the BJP into a ruling party was best seen on the floor of the House.

I remember Vajpayee leading a group of 161 BJP MPs as a solitary general — the political isolation that the BJP faced was described as “untouchability” by some leaders. In 1996, he faced the inevitable with dignity. I remember his passionate speech: “If breaking up political parties is the only way to form a coalition that stays in power, then I do not want to touch such a coalition with a barge pole”. He ended by saying, “Adhyaksh mahoday, mein apna tyag patra rashtrapati ko dene jaa raha hun (Respected Speaker, I am now leaving to tender my resignation to the President). With debates going on till late evening, all that would keep us awake was the tea, with a drop of milk, served at Panditji’s tea point.

During Vajpayee’s second stint, the BJP was dependent on the J Jayalalithaa-led AIADMK to stay in office. After 13 months, when Jayalalithaa decided to end the alliance, Vajpayee was unusually peeved. On April 17, 1999, when the screens inside the Lok Sabha showed the tally of the no-confidence motion at 269-270 – he lost the majority by one vote – the House was briefly silent before the Opposition broke into celebrations. But I could sense the sympathy and awe Vajpayee had evoked in many on the other side when he looked at the result and raised his hand to his forehead in a mock salute.

But this Parliament also witnessed the BJP, stunned after losing power in 2004, seemingly in denial about the Congress-led UPA’s rise to power. In the initial sessions, its 138 MPs disrupted proceedings. They created uproarious scenes even when Prime Minister Manmohan Singh introduced his cabinet. The UPA years were the last time Parliament saw the Prime Minister in attendance regularly.

The press gallery has its share of amusements as well. The members speak different languages and wear various outfits – there is no official dress code. Varkkala Radhakrishnan, a former speaker of the Kerala assembly, was a stickler for the rules in the Lower House. He drew tremendous respect from the treasury benches during Vajpayee’s time. Once he berated the (then) Union Minister Dasari Narayan Rao for keeping the top buttons of his shirt open while replying to questions.

Then there’s former Rajya Sabha MP Vakkachan Mattathil, who was amused when Vajpayee told him in one of the restrooms that “you are lucky to use the facilities with the Prime Minister of India.” If Shashi Tharoor is a social media sensation today for his English vocabulary, Jaipal Reddy was the wordsmith for an earlier generation. Reddy – then in the Janata Dal – took exception to the Vajpayee government’s favourable stand in the Supreme Court on allowing puja at the disputed site in Ayodhya. About Vajpayee, he said: “There is a humongous hiatus, a gigantic gap and a gargantuan gulf between his public image and private reality.”

The changes after liberalisation were reflected inside the Parliament complex. From a time when very few MPs had cars — Ambassadors or Fiats — a plethora of imported vehicles now lays siege to the complex.

Today, there is a widening gulf between political parties. The convention – honoured by all political parties — was that the Rajya Sabha would go ahead with debates even if there is conflict or pandemonium in the Lok Sabha.

But this Monsoon session – presumably the last in this building — was almost a washout!

I have spent more time in this building than at my home in Kerala. The friendships I made in the corridors of power endure. Many of the staff in the building have seen me coming to Parliament since my early 20s — switching jobs, getting married and now as the mother of the twin girls who are grown up now. This Parliament House has been a constant figure in my life over the last 25 years. I do not know if the old sense of warmth will find its way to the new building.

Parliament House

From: Subodh Ghildiyal, May 29, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Features of new Parliament building

Sengol, the golden sceptre

Pushpa Narayan, May 25, 2023: The Times of India

From: Pushpa Narayan, May 25, 2023: The Times of India

Chennai: PM Narendra Modi will be following in the footsteps of India’s first PM Jawaharlal Nehru when he receives a golden sceptre (‘sengol’ in Tamil) at the inauguration of the new Parliament building on May 28.

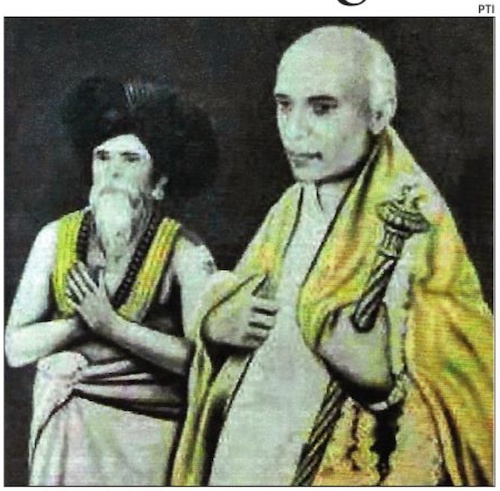

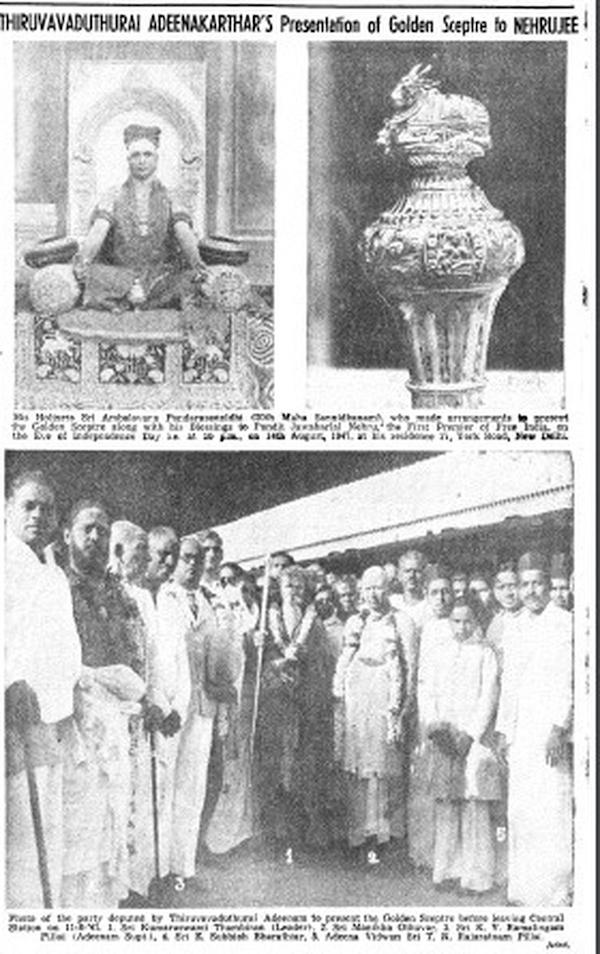

Marking the transfer of power in 1947, Nehru received the ‘sengol’ from the deputy pontiff of the Thiruvavaduthurai ‘adheenam’. This time, pontiffs of 20 ‘adheenams’ (nonBrahmin Shaivite mutts in Tamil Nadu) will preside over the rituals. They will hand over the ‘sengol’ to Modi at 7. 20am after a 20-minute ‘homam’ or ‘havan’. Modi will then install it on a pedestal to the right of the Speaker’s chair.

“The ‘sengol’ represents values of fair and equitable governance,” said home minister Amit Shah. “It will shine near the Lok Sabha Speaker’s podium as a national symbol of ‘amrit kaal’, an era that will witness the new India taking its rightful place in the world. ”

In 1947, the ‘sengol’ was made on the advice of C Rajagopalachari, the last Governor General of India, when Nehru asked his cabinet how the transfer of power from the British should be marked. Rajaji referred to the ancient Chola custom of the ‘rajaguru’ handing over a sceptre to the king on his coronation. Madras jeweller Vummudi Bangaru Chetty was commissioned to make the ‘sengol’ in four weeks.

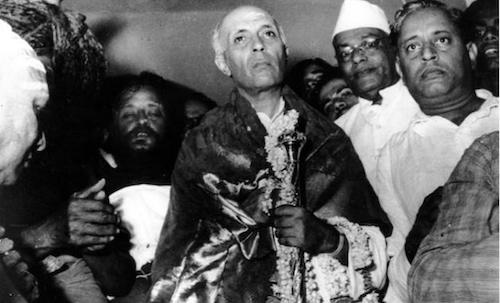

On August 14, Viceroy Mountbatten handed the sceptre over to the Tamil pontiffs who purified it and handed it over to Prime Minister Nehru at his home just before he left for Parliament House to deliver the historic “tryst with destiny” speech in the intervening night of August 14-15, 1947.

For decades, the sceptre was forgotten. It lay in a dusty box at the Allahabad Museum, wrongly labelled as a golden walking stick gifted to Nehru. This time, PM Modi will carry the sceptre in the new Parliament building, ac- companied by Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla and the pontiffs from Tamil Nadu.

Dignitaries and the mutt heads, including Thiruvavaduthurai ‘adheenam’ Sri La Sri Ambalavana Desika Paramacharya Swamigal, will stand in the Well of the House when the Prime Minister installs the sceptre on the specially designed pedestal.

At least 31 members of the ‘adheenams’ will leave Chennai for New Delhi in two batches on chartered flights. Ahead of the ceremony on May 28, Modi will honour them at his residence at 7 Lok Kalyan Marg.

History

1947

Vikram Sampath, June 7, 2023: The Times of India

Undoubtedly, a religious ritual was held in New Delhi in the wee hours of August 14, 1947, in which Nehru had reluctantly participated. Tai Yong Tan and Gyanesh Kudaisya note in The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia (2000) that alongside Rajendra Prasad, Nehru sat cross-legged around a holy fire amidst chanting of hymns. The Sengol was conferred on him, writes Perry Anderson in After Nehru (2012), by “Hindu priests (who) arrived posthaste from Tanjore for the ritual”. In a benediction to Nehru, they chanted verses of Kolaru Pathigam:“This golden Sengol is yours and symbol of our (people’s) rule… you will rule, it is my command!” In Freedom at Midnight (1975), Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins paint an evocative picture: “As once Hindu holy men… conferred upon ancient India’s kings their symbols of power, so the sanyasin had come… to bestow their antique emblems of authority on the man about to assume the leadership of a modern Indian nation. ”

Indian Express (August 13, 1947) reported that post-ritual, the Sengol was to be taken in procession to the constituent assembly hall where the secular oath-taking was to occur to the accompaniment of nadaswaram by Adheenam musician TN Rajarathnam Pillai. In 1955, criticising Nehru for participating in “Brahminical rituals”, Ambedkar scoffed about a Brahmin becoming India’s first PM and wearing the “raja dand” Brahmins gave him (Writings and Speeches, Vol I, (1979)).

In a Chola ritual on anointing, the royal priest vested the Sengol in the incumbent king’s hands. Ancient Tamil texts extol the Sengol as embodiment of righteousness, virtues and ethical rule. Journalist Dosabhai Framji Karaka wrote in Betrayal of India(1950): “It was traditional… to derive power and authority from holy men. Pandit Nehru yielded to… religious ceremony because… this was the traditional way of assuming power. The mood of New Delhi had become almost superstitious. ”

It is but obvious this was an unofficial, religious ceremony, only symbolic of the change of guard. It’ll remain a mystery if Mountbatten received it first. There are no records. But one might deduce the “posthaste” arrival of priests was to coincide with Mountbatten’s return to Delhi from Pakistan’s independence celebrations on August 14. Absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. Fact remains that a Hindu ceremony to vest the new Prime Minister with a symbol that stood for transfer of power, that was taken in procession to the new assembly, invokes more gravitas to the episode than mere private gift-presentation.

Criticising the Sengol as a monarchical symbol is forgetting that emblems of independent India – the lions, and the wheel in our tricolour – have monarchic roots to Ashoka’s Sarnath pillar. Does that make them regressive symbols of empire? Recasting ancient symbols in democracies is common practice. The old Parliament was constructed by British monarchs. Were we for 75 years then conducting legislative business in a symbol of colonial oppression? How far will one stretch demands for documentary proof, disregarding oral narratives? Are we to suspect accounts of Kanchi Mahaperiyava who recounted this first in 1978 or the Adheenam records merely because mutts and seers are not believable; their archives of inferior historical value? In Tamil Nadu, DMK government in a policy note (2021-22) to the assembly mentioned: “Swamigal handed over the gold-plated silver sceptre to Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. This signified transfer of power from the British… Lord Mountbatten to the first Prime Minister of India. ” Is DMK, a Congress ally, complicit in establishing a Hindu Rashtra too? Gandhi’s personal secretary from 1943-48 Venkita Kalyanam who was behind Bapu when he fell to bullets had confessed he was not sure if ‘Hey Ram!’ were indeed the last words. Being thus in a realm of ambiguity with no written account, do we then remove that plaque from Rajghat too?

Naysayers consistently undermine Indians’ collective memory – whether on Ayodhya or Rani Padmini’s jauhar or Tipu Sultan’s atrocities. By questioning them and quoting written evidence (possibly by a contemporary Mughal or British chronicler), they delegitimise people’s histories. The counter-narrative to the Sengol tells us more about the negative minds who’d rather besmirch a ritual than participate in the renewal of the Indian republic.

The writer is a historian & Fellow, Royal Historical Society, UK

Salient points

Alind Chauhan, May 31, 2023: The Indian Express

An ancient South Indian tradition symbolising a dharmic kingship has been ceremonially resurrected with the installation of the sceptre of righteousness in India’s new Parliament building. Here’s what the sengol meant historically, and what the ceremony suggests today.

What is a Sengol? What was the tradition associated with it? What period can we date it to and which dynasty/dynasties was it associated with?

A sengol — or chenkol — is a royal sceptre, signifying kingship, righteousness, justice, and authority, among other qualities linked to the correct wielding of power. Its origins lie in Tamil Nadu, and it served as a kingly emblem. Among the Madurai Nayakas, for example, the sengol was placed before the goddess Meenakshi in the great temple on important occasions, and then transferred to the throne room, representing the king’s role as a divine agent.

It was also, therefore, a legitimising instrument: the Sethupatis of Ramnad, for instance, when they first attained kingly status in the seventeenth century acquired a ritually sanctified sengol from priests of the Rameswaram temple. It marked the ruler’s accountability to the deity in the exercise of power, as well as his graduation from chiefly status to a more exalted kingly plane.

As such, the sengol may be described, in its historical context, as a symbol of dharmic kingship.

What do we know about the 1947 ceremony in which Nehru was reportedly handed over a sceptre?

Not enough. What seems to be in the air at the moment stems from some oral accounts mixed with a few scattered facts. It appears that Nehru was presented a sengol by Hindu leaders from Tamil Nadu, and that he accepted it.

But claims that it was a major event, and that Lord Mountbatten handed it over in a ceremonial fashion to signify the transfer of power, seem exaggerated. Something of that nature — given the importance of the moment — would have been widely recorded and reported. Mountbatten himself — a great lover of pageantry, with an inflated sense of his own centrality to events — would not have omitted to make a big hoo-ha about the affair.

The very obscurity of this sengol and the absence of adequate contemporary evidence suggests it was not a key episode in 1947, but an incident on the margins. The Hindu leaders presented it to Nehru as a mark of honour, and he, in turn, received it in good spirit. But that was that. From what is known of Nehru’s personality, besides, he was not the type to be drawn to kingly rituals. It is not surprising that the item was packed off to a museum.

The government said it was C Rajagopalachari who suggested the particular ceremony to Nehru. Is this true? If yes, why did Rajagopalachari suggest it?

Only the government can answer this. One trusts they have done their research and will put into the public domain the requisite documents and information backing their stand. After all, the claim being made is big; it must be sustained with equally firm evidence. It is likely that beyond the fact of Tamil Hindu leaders presenting Nehru a sceptre, the rest of the tale is gloss, accumulated over several retellings, and which came to be believed in some circles.

This kind of thing is not unusual in our country, and historians often discover that seductive tales have a grain of truth, with the rest being wishful colour and romance. We often encounter situations where there is enough fact to make the narrative seem credible, until on closer examination, the story falls apart, leaving a pale residue. But that said, this residue is never attractive in terms of public imagination; people often prefer the heady narrative to the facts.

(Manu S Pillai is an author and historian of South India. His first book was the award winning The Ivory Throne: Chronicles of the House of Travancore (2015); he has since written three more books, most recently, False Allies: India’s Maharajahs in the Age of Ravi Varma (2021).)

Details

Arun Janardhanan, May 27, 2023: The Indian Express

Up until 2018, the current generation in charge of Vummidi Bangaru Jewellers, a chain of jewellery stores in Chennai, was unaware of the part the family had played in the “transition” of power as India awoke to life and freedom on August 15, 1947.

The family was responsible for creating the Sengol (sceptre) — derived from the Tamil word semmai, meaning righteousness, according to an official document — that India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru during a ceremony held at his residence on the eve of India’s Independence.

With the Sengol now being celebrated as a symbol signifying the transition of power, senior members of the Vummidi family, including 97-year-old Vummidi Ethiraj, will be honoured at the opening of the new Parliament on Sunday. Ethiraj’s son Vummidi Udaykumar, 63, told The Indian Express that his father will travel to Delhi on Saturday to participate in the event. On Wednesday, Union Home Minister Amit Shah had announced that Prime Minister Narendra Modi would have the Sengol installed in the Lok Sabha, near the Speaker’s podium. It will also be on display during significant national holidays.

Historical significance

Until a piece about the Sengol appeared in a Tamil magazine in 2018, the current generation of the Vummidi family had no idea about its historical significance.

Udaykumar said, “The article included a picture of the Sengol and gave our family credit for its creation. It mentioned my grandfather’s name, Vummidi Anjalelu Chetty, who passed away in the 1960s, and described my family as a traditional family of goldsmiths.”

After reading the article, Udaykumar said he asked his father about the Sengol. In 1947, Ethiraj, then 22, was a contributing member of the family businesses. However, his father could not recall any details.

“He said he couldn’t remember what he had done at the time but had a hazy memory of working on something similar. However, one of our relatives started looking for the Sengol and began contacting various agencies before he learned that the Allahabad Museum had something similar to what we were looking for,” Udaykumar said.

At the museum, the Sengol had been labelled as Nehru’s “golden walking stick”.

Arun Kumar, a member of the family’s marketing team, was sent to the Allahabad Museum. “At the museum, he was allowed to examine the Sengol closely. Based on the picture we already had from the magazine, Kumar was able to confirm that there were some Tamil letters on the Sengol. We verified that it was the same as what my father and grandfather made when India gained freedom,” said Udaykumar.

He added that the family wanted specifics of the Sengol to create a replica “to maintain at our home… That was the whole purpose of this search”. Around the same time, an R S S ideologue who is also a family friend became interested in the Sengol.

“S Gurumurthy’s Thuglak (a Tamil magazine) also published a piece on the Sengol around the same time. He began a parallel investigation to learn more about Sengol’s past. He was the one who contacted the Thiruvavaduthurai Adheenam,” Udaykumar said.

The Adheenam, a Hindu mutt in Tamil Nadu, had commissioned Vummidi Bangaru Jewellers to create the Sengol, according to a Government of India website. To a query, a top source at the mutt said it was being run by Guru Mahasannidhanam Sri La Sri Ambalavana Desika Swami, the twentieth seer, at the time.

Special gesture

“We do not have the precise details on commissioning it or the cost incurred in its making, except to say that it was a special gift and a gesture we sent from Tamil Nadu during Independence, like similar gestures shown by states and kingdoms across India,” the source added.

According to the Vummidi family, as quoted on the government website, the Adheenam gave it the task of designing the Sengol. Made of gold-plated silver, about 10 gold craftspersons worked on it for 10-15 days, added the website.

After they managed to confirm that the Sengol was in Allahabad and Kumar returned with more information and pictures, Udaykumar said his father was able to recall a few more details.

“We sat with him once again. He remembered a little more after seeing Nandi (the divine bull) perched atop the Sengol. He said there were confusions about Nandi’s proportions and that they travelled all the way to Kumbakonam for references on Nandi before settling on the final design. He remembered that they used a design sent by the Adheenam for the Sengol,” Udaykumar said.

According to Ethiraj, said Udaykumar, the surmounted Nandi denotes stability and justice. Motifs like wheat and rice grains, indicating the prosperity of agriculture, and Goddess Lakshmi, representing wealth, were carved on the remaining parts of the Sengol. “My father said it was a symbolic statement — that the person who holds the Sengol will also possess all of these things,” he said.

He added that neither his father, nor documents with the family and the Adheenam had proof or information regarding the cost or material used in the creation of the Sengol.

“We don’t have this information. My father has no recollection of these specifics either. Our home, workshop and showroom were all located at the same location back then — on Govindappa Street in Sowcarpet. More than 25 people worked for us. My uncle was barely 12 years old at the time. So he was unable to recall any details. The only thing my family remembers is that before the Sengol was sent to Delhi, people came to see it,” Udaykumar said.

The sceptre is mentioned in an article on India’s independence in Time Magazine’s issue dated August 25, 1947. Under the subheading, ‘Blessing with Ashes’, the article states that even an agnostic like Nehru, as he was about to become India’s first Prime Minister, “fell into the religious spirit”.

The article, titled ‘INDIA: Oh Lovely Dawn’, vividly described how Sanyasis “from Tamil Nadu visited Nehru’s house on the eve of independence” and “sprinkled Nehru with holy water from Tanjore and drew a streak in sacred ash across Nehru’s forehead”. It added that the seer from Tamil Nadu gave Nehru the golden sceptre — described in the article as the “scepter of gold, five feet long, two inches thick” — after wrapping him in the pithambaram “(cloth of God), a costly silk fabric with patterns of golden thread”. Additionally, the article said he gave Nehru some cooked rice that had just been flown to Delhi after being offered that very morning to the dancing god Nataraja in south India.

Lack of documentary evidence

According to a document released by the government, when Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, asked Nehru if there was a ceremony that should be followed to symbolise the transfer of power from the British to the newly independent nation, the soon-to-be Prime Minister consulted C Rajagopalachari, the last Governor-General, who suggested a Chola dynasty tradition — where the transfer of power from one king to the other was sanctified and blessed by high priests.

“The symbol (for the transfer of power) used was the handover of the ‘Sengol’ from one King to his successor,” says the document.

Congress communications head tweeted there was no documented evidence of Lord Mountbatten, Rajagopalchari and Nehru describing the ‘Sengol’ as a symbol of the transfer of power by the British to India.

The government hit back, with Amit Shah asking why the party “hates Indian traditions and culture so much”.

“A sacred Sengol was given to Pandit Nehru by a holy Saivite Mutt from Tamil Nadu to symbolize India’s freedom but it was banished to a museum as a ‘walking stick’,” Shah tweeted.

Srila Sri Ambalavana Desika Paramacharya Swamigal, the leader of the Thiruvaduthurai Aadheenam, admitted to the lack of documentary evidence to arrive at a specific conclusion either way.

“These are all the stories we have heard from old people… What we know is that a Sengol was presented by the Aadheenam to Nehru when India got Independence.”

The book, Freedom at Midnight, authored by Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins, mentions how Tamil seers handed over the Sengol to Nehru on the eve of Independence. The book vividly details their procession in a 1937-model Ford taxi through Delhi on the evening of August 14, which “came to a stop in front of a simple bungalow at 17 York Road,” Nehru’s residence between 1946 and 1948, before moving to Teen Murti House. The 17 York Road is now called Motilal Nehru Marg.

“As once Hindu holy men had conferred upon ancient India’s kings their symbols of power, so the sannyasin had come to York Road to bestow their antique emblems of authority on the man who was about to assume the leadership of a modern Indian nation,” says the book about Tamil seers meeting with Nehru at his residence.

The book also captures the moment when seers placed their sceptre in Nehru’s arms: “To the man who had never ceased to proclaim the horror the word ‘religion’ inspired in him, their rite was a tiresome manifestation of all he deplored in his nation. Yet he submitted to it with almost cheerful humility. It was almost as if that proud rationalist had instinctively understood that in the awesome tasks awaiting him no possible source of aid, not even the occult that he so scornfully dismissed, was to be totally ignored.”

Evidence thin on claims about the sceptre

PON VASANTH B.A, May 27, 2023: The Hindu

From: PON VASANTH B.A, May 27, 2023: The Hindu

From: PON VASANTH B.A, May 27, 2023: The Hindu

From: PON VASANTH B.A, May 27, 2023: The Hindu

A day after Union Home Minister Amit Shah addressed a press conference in Delhi explaining the importance of the sceptre (sengol) to be installed in the new Parliament building, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman addressed journalists in Chennai on May 25, explaining how it is a matter of pride for Tamil Nadu.

She reiterated that it was the ritual of handing over of this sceptre, made by the Thiruvavaduthurai Adheenam in Tamil Nadu, to India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on the eve of Independence that actually symbolised and sanctified the “transfer of power” from the British to India.

The Frequently Asked Questions section in the website (www.sengol1947ignca.in) launched by the Union government says the handover of this sceptre was “the defining occasion that actually marked the transfer of power from British to Indian hands…The ‘order’ to rule India was thus received, suitably blessed”.

The government’s assertion is that Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of India, asked Nehru if there was any procedure to signify transfer of power. Nehru in turn consulted C. Rajagopalachari, the last Governor-General of India, who in turn had the Thiruvavaduthurai Adheenam prepare the sceptre, seen as the sacred symbol of power and just rule. Those who presented the sceptre were flown in a special plane to Delhi, the government said.

There is ample evidence that a delegation sent by Sri la Sri Ambalavana Pandarasannadhi Swamigal, the head of the Adheenam, presented the sceptre to Nehru, accompanied by the recital of hymns from Thevaram. However, evidence is thin on the government’s claim that this presenting of sceptre was treated by the leaders and the then government as the symbolic transfer of power.

When asked about the documentary evidence, Ms. Sitharaman said there were “as many documentary proof” as one wanted and they were included in the docket given to the reporters at the end of the press conference.

A perusal of these documents, however, did not establish the claims of the government. The documentary evidence included a list of references from books, articles, and reports in the media. It also included social media and blog posts from individuals.

The reports from Indian newspapers, including The Hindu, had briefly recorded the presentation of the sceptre. None spoke about it being a symbol of transfer of power or it being taken on the advice of Rajaji. Importantly, a picture carried in The Hindu showed the delegation at the Central Railway Station, Chennai, on August 11, 1947, before leaving for Delhi. This indicates the delegation had most likely travelled by train and not by a special plane.

Other evidence referred included an article in the Time magazine on August 25, 1947. Speaking on the happenings on August 14, 1947, it says, “From Tanjore in south India came two emissaries of Sri Amblavana Desigar [the head of Thiruvavaduthurai Adheenam], head of a sannyasi order of Hindu ascetics. Sri Amblavana thought that Nehru, as first Indian head of a really Indian Government ought, like ancient Hindu kings, to receive the symbol of power and authority from Hindu holy men”. While it speaks about the head pontiff’s idea of the sceptre as symbol of power, it does not speak about Nehru reciprocating the same idea or seeing its presentation as the symbol of power transfer.

The book Freedom at Midnight, cited as evidence, also says something similar. “As once Hindu holy men had conferred upon ancient India’s kings their symbols of power, so the sannyasin had come to York Road to bestow their antique emblems of authority on the man [Nehru]... To the man who had never ceased to proclaim the horror the word ‘religion’ inspired in him, their rite was a tiresome manifestation of all he deplored in his nation,” it says.

Other evidence cited included the excerpts from Ambedkar’s Thoughts on Linguistic States, Perry Anderson’s book The Indian Ideology, and Yasmin Khan’s Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan, all of which were critical of certain religious rituals in which Nehru participated, but none about the use of sceptre as a symbol of power transfer.

Importantly, none of the evidence presented said the sceptre was first symbolically given to Mountbatten and taken back before being presented to Nehru, symbolising the transfer. The exception is the article that appeared in Thuglak magazine, written by its editor S. Gurumurthy in 2021. The article records everything the government has said as the version shared by Sri Chandrasekarendra Saraswathi, the 68th head of Sri Kanchi Kamakoti Pitam, from his memory to a disciple in 1978.

The most ironic evidence presented in the docket was a blog post titled “WhatsApp History” written by famous Tamil writer Jeyamohan. In this post, Jeyamohan had in fact ridiculed this version of events as being based on forwards on social media. Stating that the sceptre was likely to be among the many presents sent from across the country during Independence, he , however, said it was a matter of pride for Tamils that the sceptre from the Saivite mutt also reached Nehru.

The document also mentioned the annual policy note prepared by Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department in Tamil Nadu for 2021-2022, stating the sceptre “signified the transfer of power”. Officials from the department could not clarify on the source for this statement when contacted on May 25. The reference has been removed from the department’s policy notes in 2022-23 and 2023-24.

C N Annadurai: On the Sengol and Nehru accepting it

C N Annadurai, Translated by V Geetha, May 29, 2023: The Indian Express

C N Annadurai, founder of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam and former chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, has referenced the Sengol in an article by that name in the weekly Dravida Nadu (24.8.1947) that he edited. Written with the rhetorical flourish that was the hallmark of his satiric imagination, the piece comprises several parts – including an imagined conversation between the author and a friendly though clueless interlocutor and one between a modern brahmin intellectual and the Adheenam. Primarily, in this essay, Annadurai wonders at the reasoning behind this handing over of the sceptre to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Here is a rough translation of parts of this essay.

The Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam has handed over a Sengol to Pandit Nehru, who is the Prime Minister of the new government. … Why did he do this? Was this a gift, an offering, a licence fee? It is certainly unexpected. And unnecessary. But if it were only unnecessary it wouldn’t matter. There is deep meaning in this gesture, and it is becoming increasingly clear that it bodes danger.

We don’t know what Pandit Nehru thought of this and neither do we know if the Thiruvaduthurai Adheenam sent a note along with it. But we have a few words for Pandit Nehru.

You are well aware of the histories of nations. An anointed King who put his subjects to work so that his cohort of nobles could live off their labour. Within the King’s golden castle there are men who have the freedom and permission to wander within its precincts. Men who are in possession of religious capital. If we are to sustain the rule of the people, such men ought to be stripped off their privileges is a historical truism. You know this. The question that worries those like the Adheenam is this. They wonder with some anxiety if your government will act on this knowledge and they are likely to bring forth and offer you, not just a golden scepter, but one embellished with nine gems, all because they wish to protect their self-interest.

This is not a sceptre brought forth by the devotee seeking God’s grace by his ardent singing… no, the Adheenam’s gift has been wrought by people’s labour. The gold that has gone into its making is paid for by those who do not care that there are the poor who go hungry day and night, who have misused the wealth of others, hit the peasants in his belly, paid workers the least that they could, not honored their debts, multiplied their profits. And who in order to hide their wrong doing, their sins, and to cheat God have poured their offerings to him by way of this gold. If our future rulers are to receive this sceptre from those who are in the habit of exploiting bodies and minds, that does not bode well.

Brahmin: That you, the Adheenam would send this Sengol in an auspicious hour, out of your sheer love, respect and concern, to the new government, why this will earn you the praise of our princes, of Jaipur, Baroda, Udaipur, Mysore… They might refer to the Sengol for a minute or two, but in reality will sing your praises the whole day.

Adheenam: Wasn’t that a good idea, to send it?

Brahmin: The Sengol is what the King holds in his hand. And who handed over such a Sengol to the government? The Adheenam, who thus lent his stamp of approval, by granting the scepter, as if he were blessing the new government, granting it permission to start functioning – this is what will be the talk of the town. Not only now, but in the future as well.

Take a look at the Sengol. It is beautiful. But perhaps you can see more than the sacred bull, the rishabam. You can also see thousands of acres of land, planted worked over by the agricultural worker, who is reduced to a life of sorrow. You will also be able to see his hut, and the poverty therein, presided over by this sceptre. You will also see the mirasdar, his bungalow, the golden plate he eats from. And again, the tired body, with its overwrought eyes… you will see the mutt, and the ascetic with his dread locks, his beads, the gold in his ears, his golden slippers.

…This Sengol sent to Pandit Nehru is no gift offering. Or a symbol of love. Or for that matter, an expression of patriotism. It is a request to the future rulers of India that they spare the adheenams and not take away their wealth and glory. By offering this to our rulers the Adheenam is seeking their friendship, so that their fame and domination do not wither away.

…All this gold in the possession of these ascetics, yet it is a speck of what they actually hold. If all the gold in their premises is confiscated and spent on the common good this sceptre will cease to be a decorative symbol and instead become a means to improve the common person’s life.

Indian arts and crafts

Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From: Shiny Varghese, June 1, 2023: The Indian Express

From a wooden block of red sheesham used by a family of block-print artisans in UP to an eight-foot-long representation of Varanasi made in pure silk, Parliament's Shilp Gallery is home to rare installations

How does one tell stories of a centuries-old journey? Of dye-stained hands and nimble fingers that speak of seasons, birth and life? How does one talk about faith through the nation’s soil? The answers to these have found their way into the Shilp Gallery of the new Parliament – home to eight rare installations by 300-odd workers and one of three such galleries dedicated to the arts.

While the Shilp Gallery, entry to which is from the old Lok Sabha side, is completed, the Sangeet gallery for the dance and music traditions of India and the Sthapatya gallery, dedicated to the country’s architectural heritage, are works in progress.

In the gallery, Kafeel’s metal-on-wood tree of life inlay work and his father’s block are part of the installation ‘Samrasta (diversity)’. “Hum ne kabhi nahi socha ki hamara kaam ek din Sansad mein hoga. Ek karigar akele nahi pahunch pata (I had never imagined that our work would be in Parliament one day. One worker wouldn’t have been able to make it on his own),” says the 50-year-old.

From using traditional forms of storytelling such as the kavad to showcase the festivals of India, or calligraphy to present the different scripts of India through poems, sayings and shloka, to block art such as Kafeel’s, the gallery is a rich layering of India’s numerous crafts.

“It was exciting to have craft given such an important place. It was a way to showcase all that we have as a country,” says Jaya Jaitly, president-founder, Dastkari Haat Samiti, who has brought together eight installations under themes that were given by the Ministry of Culture. These include — Gyan (knowledge), Prakriti (nature), Aastha (faith), Ullas (happiness), Parv (celebration), Swavlamban (self-reliance) and Yatra (journey).

Jaitly, who has been travelling for four decades across the country, working with different handicraft groups and artisans, brings her creative expertise to this gallery. On her team were over 300 craftspeople, and the Delhi-based design firm Abaxial, helmed by principal architect Suparna Bhalla.

The ‘Prakriti’ installation by Mathura-based Manoj Kumar Verma, a fourth-generation Sanjhi artist, is themed on the harmony among man, nature, bird and beast and goes beyond an art form that was once only seen in temples.

“Wherever we go, we absorb everything we see – trees, plants, birds and when we sit with our art, they all come alive. I must confess what I see, what I think and finally what emerges on paper is very different, the hand moves differently,” says the 52-year-old. In the fine filigree work, one finds a tiger lurking, and mango, peepal and kadam trees, peacocks, even a procession.

The journey continues to Varanasi, where the ‘Yatra’ installation stretches eight feet across the wall. Handwoven in pure satin silk with pure silver and gold zari, the silhouette of the riverfront of one of India’s oldest cities comes alive. The journey, from the left of the piece, begins at Ganga Mahal Ghat, an extension of Assi Ghat, and moves to Raj Ghat. The artisans first photographed each of the ghats before drawing the blueprint for the loom.

“It is the single largest weave of its kind ever,” says Bhalla, of the work that took over 42,000 jacquard punch cards to be woven into a single piece. “You can match the skyline with what’s on the ground, they have replicated every building, including a tilted temple, on the woven fabric. To me, that signifies the imperfections that something handmade allows. Craft is about accepting us with all our flaws and that is the beauty of this. Likewise, in the ‘Samrasta’ installation, we asked artisans from different parts of the country to give us blocks they used. We didn’t want new blocks, pristine polished ones. It had to tell the story of their fathers and their grandfathers, their mothers, their families. The point of wood itself has to do with age and civilisation. We wanted that legacy and heritage represented. Its patterns such as these that make our country,” says Bhalla.

Jaitly affirms, “The idea was that the old building blocks make a new India.”

While ‘Aastha’ could have gone down the road of prayer beads and symbols, Jaitly looked at soil as a metaphor for faith. “When students return from their studies abroad, they apply the desh ki mitti on their foreheads. It’s a way of saying that the soil of one’s country is what we should have faith in. So we got mitti from every state. Some states don’t have pottery as a traditional craft, so army officers, civil aviation officers, friends send us soil from river beds,” she says. There’s soil from Andaman jail, riverbeds in Meghalaya, sands of Daman and Diu, even a teapot from a Ladakh potter’s family, halfway up a hill.

Ajrakhpur artisan Juned Ismail Khatri’s craft is 10 generations old. “My ancestors worked with natural dyes and over the years, chemicals came into the market. It’s only during my grandfather’s time that we went back to natural dye. Prepared over a 20-step process, each ajrakh fabric is unique, based on how the climate works on the dye. Our installation is called ‘Swavalamban’, which means self-reliance or resilience. What better way to show this idea than through the khadi we print on and the patterns we make,” he says.

What was most rewarding about working on this project? “To have guards and labourers on the construction site come up to see the work. They would look for a representation of their own region in the installations and tell us, “Yeh tho hamare yahan ka hai (this is from our place),” says Bhalla.

A sparkling building

Salient features of the 2023 building

May 29, 2023: The Times of India

From: May 29, 2023: The Times of India

Statues at the six entry-exit points or dwars in the new Parliament building have been inspired by ancient sculptures. While the two elephants made of stone at Gaj Dwar, which the Prime Minister used to enter the building for inauguration, has been inspired by statues at Madhukeshwara temple at Banavasi in Karnataka dating back to 9th century CE, the Ashwa Dwar has got two statues of horses inspired by the sculptures at Sun temple in Odisha of 13th century CE.

The statues at three other dwars — Shardula, Hamsa and Makara — are inspired by sculptures from Gujri Mahal at Gwalior, Vijay Vithala temple at Hampi and Hoysaleswara temple in Karnataka.

The remaining Garuda dwar dons the statues of mount (vahana) of Vishnu have been inspired by 18th century CE Nayaka period sculpture of Tamil Nadu.

Epitome of India’s diversity

The PM highlighted how the new building has accommodated the vast diversity of the country. The interior of the Rajya Sabha is based on the national flower lotus. National tree, banyan, is also there on the premises of the Parliament. Granite and sandstone brought from Rajasthan have been used. The wood work are from Maharashtra. The artisans of Bhadohi in UP have hand woven the carpets. In a way, we will see the spirit of ‘Ek Bharat, Shrestha Bharat’ in every particle of this building, the PM said.

Chits & letters keep Shah busy

Home minister Amit Shah was a busy man even while seated inside the Lok Sabha Hall of the new Parliament building for the inaugural function. Sharing the seat with Nitin Gadkari, Shah was seen receiving chits and letters frequently and twice he was helped by Gadkari to take the epistles being carried by the security staff.

Harivansh scores a hat-trick

Deputy chairman of the RS Harivansh, seated along with PM Modi and Speaker Om Birla on the dais, was a busy man. Other than receiving the PM along with Birla, he spoke thrice. . . apart from his own speech, he also read the messages of President Droupadi Murmu and VP Jagdeep Dhankhar. A former journo, Harivansh was best at modulations as he could be seen assertive when he read references about why PM has rightly inaugurated the new building as the Prez and the VP had mentioned in their messages.

Pendulum shows ties with universe

One of the biggest attractions in the new building is Foucault’s Pendulum, which hangs from a large skylight in the triangular roof of the Constitution Hall and signifies the relation of India with that of the universe. The pendulum and its relative rotation is proof of the rotation of the earth around its axis. At the latitude of the Parliament, it takes 49 hours, 59 minutes and 18 seconds for the pendulum to complete one rotation, as per the details displayed at the installation. It has been designed and installed by the National Council of Science Museums.

PM’s gracious welcome to Gowda

Special references to the presence of former Prime Minister HD Deve Gowda were made during the inaugural ceremony. Even the PM was seen gracious to him when he went to the different rows to greet the attendees. While Deve Gowda himself was there, so was AP CM Jagan and Akali Dal chief Sukhbir Singh. Naveen Patnaik, however, had deputed his party leaders Sambit Patra and Bhratruhari Mehtab, who were present at the function.

Yogi obliges ‘fans’ with selfies

Prime Minister Modi was the centre of attraction and received a thunderous welcome on arrival for the inauguration ceremony. However, Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath was seen surrounded by lawmakers for selfies, group photos and a few touching his feet to seek his blessings. Seated in the front row, as were the other chief ministers, a composed Yogi obliged them all and was also seen sharing lighter moments with a few of them, one being BJP’s Rajya Sabha MP Sudhanshu Trivedi.

Easy entry, but exit for vehicles tough

Contrary to apprehensions regarding traffic restrictions, movement of labelled vehicles was smooth and one could reach easily up to the entrance gate, which still is the same that of the old building. However, post ceremony, most of the MPs and ministers had long waits for their respective cars

IT-savvy, but rich in culture too

Making the new Parliament building technology -savvy even for visitors, the government has put QR codes at all gates, galleries and installations, enabling people to get the details on their phone in seconds. There are three sections for exhibitions on the ground floor — Sangeet Dirgha (Indian classical music and instruments), Sthapatya Dirgha (rich heritage of Indian architecture), which exhibits the achitecture of Unesco and Archeological Surbey of India monuments, and crafts from across India made by 400 artisans (Shilpa Dirgha). In the central foyer, a massive 75-ft long artwork ‘Manthan’ is on display and there is a ‘People’s Wall’ displaying the folk art painting from across the country.