Armenians in India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

Armen Sarkissian’s overview

Written by Armen Sarkissian, Dec 30, 2022: The Indian Express

Armen Sarkissian writes: The partnership between Armenia and India is not driven by governments alone. It is pushed forward to a great extent by ordinary people from both countries. Governments need to catch-up.

Few nations occupy a more exalted position in our national memory than India — the land where generations of Armenian diaspora communities have thrived and gave shape to the dream of reviving the Armenian state, which had been obliterated over centuries of invasion and rule by foreign powers. Take, for instance, the Mamikonians, a revered aristocratic dynasty which controlled vast swathes of Armenia until the 8th century. A branch of the family moved between Armenia and India, and the greatest warrior it produced — the fifth-century military commander Vartan Mamikonian — bore a Sanskrit name.

Centuries before Vartan Mamikonian led his forces in defence of Christianity against the Persian army, a pair of Indian princes from Magadha had taken refuge in Armenia and even been allowed to raise Hindu settlements. That warmth and liberality were reciprocated by Indian rulers as late as the Mughal era. In 17th-century India, Armenians were highly valued for their artisanship, granted trade privileges, and taken on as advisors by royal courts. So extensive was the network of Armenians in India that by the 19th century, Kolkata — home, among other Armenian-Indians, to the fabled classical singer Gauhar Jaan — had gained a reputation as an Armenian city.

It was in Chennai, however, that ideas of resuscitating the Armenian state first bloomed. As early as 1773, Shahamir Shahamirian, the great Armenian nationalist based in southern India, published his pamphlet on a future Armenian state – a work that has justly come to be regarded as both a roadmap and a draft constitution for a reconstituted Armenia. Two decades after Shahamirian’s book, the first Armenian language journal, Azdarar, was published from Chennai. Together, these two works of print galvanised Armenian communities around the world and sparked a national consciousness. The Armenian republic which existed briefly between 1918 and 1920 was the culmination of an aspiration that had acquired wings in India.

The Armenian republic which was reborn in 1991 was recognised by India a day after the Soviet Union’s demise. New Delhi chose Yerevan, the Armenian capital, as the site of its first embassy in the Caucasus. My own career as a diplomat and politician, which began in the 1990s, was enhanced by the friendships I forged with Indians —from groundbreaking scientists to pioneering businesspersons and visionary politicians — and influenced by the lessons I learnt from India’s struggle for freedom.

In 2018, days after being sworn in as the fourth president of Armenia, I was confronted with the most formidable political challenge in Armenia’s post-Soviet history as tens of thousands of demonstrators gathered in the capital to demand the expulsion of the then prime minister. The protest has since been titled the “velvet revolution”, but there was nothing at the time to suggest that it was going to end peacefully. The slightest miscalculation by either side could have resulted in carnage. The Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day, which is marked every year on April 24, was around the corner. I feared that we were on the verge of disgracing that solemn occasion.

Although my role was largely ceremonial, I was adamant that something had to be done. The impetus for what came next emanated from my reading of Mahatma Gandhi, who in my opinion set the highest standard for personal conduct in politics. I told my advisors that I was going to meet the protestors. They baulked at the idea and said plainly that my security detail could not guarantee my safety. But the people massed outside the presidential palace were my compatriots. I could not function as their president if I feared them. So I walked out of the palace and into the crowd and shook hands with the people. Seeing that their first citizen was not some distant figure, they spoke freely. This breakthrough was worth every risk to my life. Suddenly, there were cheers. And instead of a bloodbath, Armenia experienced a peaceful transfer of power in the weeks that followed. This is a story I remember fondly because it speaks to the enduring power of nonviolence.

There are, however, still occasions when force is unavoidable, especially when it comes to nationhood and sovereignty. Over the past half-decade, India has emerged as Armenia’s pre-eminent defence partner. The current leadership of India is unafraid to speak bluntly about the ongoing aggression in the Caucasus, including the blockade of the Lachin corridor that has cut-off 1,20,000 Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh from the world. As Armenia’s president, I cherished my excellent relations with India and it is heartening to see Delhi’s solidarity with Armenia in this time of crisis.

Armenian communities in India

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Synonyms: Hay [West Bengal]

Surnames: Arathun, Basil, Grigory, Poladian, Sukias [West Bengal]

Armenians in India, city-wise

Chennai

A SLICE OF ARMENIA The Times of India

Dr S Suresh walks down the hallowed corridors of the Armenian Church and gives us a glimpse of its history and architecture…

Chennai has the rare distinction of being one of the few Asian cities that had a sizeable population of Jews and Armenians a few centuries ago. Indeed, the Armenians and the Jews were among the earliest foreign traders to settle in this city. They mostly lived in and around George Town. The Armenians were known for their wisdom and sincerity. Many of them worked, along with the British, in the various government offices in the city. The British were so impressed by the efficiency of the Armenians that they gifted large tracts of land to the community and even built a timber church for them near Fort St George.

The Armenians designed and built a few buildings for use by the British population of this city. One of the largest and most important amongst these buildings is the Clive House, also known as Admiralty House, built within Fort St George in the early eighteenth century by an affluent Armenian merchant named Nazar Jacob Jan. Presently, the Armenian church in George Town is, however, the sole visible testimony of the presence of the Armenians in this city.

The Armenian church, also known as the Armenian Church of Virgin Mary, is located on Armenian Street, not too far from the NSC Bose Road and the Law College and the High Court. The church was built in 1772 but according to some locals, it was originally built in 1712 and expanded and rebuilt in 1772 on the site of the old Armenian cemetery. The church was the result of the efforts of Aga Shawmier Sultan, a prominent Armenian trader. He gifted his ancestral land for the erection of this church.

Unlike many other churches and other religious buildings in George Town and other parts of Chennai, the Armenian Church is built within a spacious courtyard enclosed by high walls. From the street, the courtyard is accessed through tall black wooden doors set within a large entrance on a platform. The secluded courtyard has several gravestones and a lovely garden and thus provides a striking contrast to the din and noise of the crowded streets in the neighbourhood. The church is mainly built of bricks and is plastered with lime. The exterior walls are profusely ornamented. The imposing bell tower is located to the south of the main church building. The bell tower houses some of the largest bells of the city. Art historians have described the church as a specimen of the famous Baroque style of architecture that was very popular in Europe, mainly Italy, in the seventeenth century.

In recent decades, there has been a marked decrease in the population of the Armenians in Chennai. Presently, only a few families belonging to this community reside in the city. Hence, the church is not extensively used. Sometimes, it is used by members of other Christian sects. Thus, the church is now more a heritage building than a religious monument. Although closely linked to the early history of the British rule in India and presently well-preserved by the owners, the church, unfortunately, does not attract many tourists.

The writer is the Tamil Nadu State Convener INTACH

Kolkata

The Times of India, Apr 24 2016

Ajanta Chakraborty

Armenia still lives in the heart of Kolkata

City's 195-year-old Armenian school had a near-death experience when its student body shrank to one. But it has now returned to life, thanks to immigrant students

What Parsis were to Mumbai, Armenians were to Kolkata -a refugee race that washed up on Indian shores before the British, and proceeded to establish iconic businesses and institutions that live to this day.One such in Kolkata is the Armenian College and Philanthropic Academy (ACPA), nearly two centuries old.

Built in 1821 as a residential school for children of Armenian descent, ACPA was founded by two Armenian merchants, Astvatsatur Muradkhanian and Manatsakan Vardanian who hailed from Julfa (now in Iran). The school was founded to impart an `Armenian' education to its students, in their language, and about their culture.

In the early 19th century, the Armenians were a prominent business community in Kolkata that ran coal mines, indigo and shellac businesses, and built some of the city's famous landmarks, including Stephen Court on Park Street and Grand Hotel (today Oberoi Grand).

But after the British quit India, so did most of the Armenians, who migrated abroad. Half a century ago, Kolkata's Armenian population dwindled to just 2,000, vanishing still further to leave behind only around 150. Two of these Indo-Armenians are counted among the 68 students currently studying at the school; the rest are immigrant Armenians from Iraq, Iran, Russia and Armenia.

The school -in whose original building novelist William Makepeace Thackeray was born -has had its ups and downs. Its student body shrank and expanded -going from 138 in 1932, to 149 in 2003, and even plummeting to a solitary student in 1990, perhaps marking the most trying year in the school's long history.

In February 1999, a Calcutta high court ruling transferred the school's administra tion to Armenia's Mother See of Holy Etch miadzin, the administrative headquarters of the Armenian Apostolic Church. It is now the Pope of Armenia who appoints the school manager.

“Since the institution's guardianship was vested with the church, the school has maintained its standards and a minimum number of students,“ said Rev. Zaven Ya zichyan, manager of Armenian College and pastor of the Indian-Armenian Spir itual Pastorate.

Following the transfer of power, the first batch of 34 immigrant students reached Kolkata from Iraq, Iran, Russia and Arme nia -sent here for the free education and boarding provided by the school. Often, Armenian families in places like Iraq and Iran send their children here even as they plan to migrate to the West, the school be coming an interim harbour for their chil dren. ACPA now routinely invites the dias pora abroad to enroll their children here.

In the run-up to their 200th year celebra tions in 2021, Rev. Yazichyan has been at tempting to revive the institution. Among the ambitious projects is the preservation and digitization of the Araratian library, set up in 1828 and named after Mount Ara rat, the place where Noah's Ark landed after the Flood. Other efforts include the creation of a databank of all Armenians from Kol kata (the last was created in 1956) and for mal associations with other international educational organizations.

To retain a cultural identity , ACPA teach es Armenian history , language and religion.

On visiting the campus on Free School Street (some say it got its name from the free Armenian school), the students seem content. Hovhannes Saringulyar, who teach es Armenian history, says, “If they miss their parents, they talk to them on Skype.“

Surat

A decline, 1980-1800

The Guardian, 15th Jun 2013

Seth, the Armenian historian, writes: “The decline and dispersion of the Armenians at Surat must have been very rapid.… During the last two decades of the 18th century (1780-1800), there were 33 (Armenian) merchants besides many others in the humbler walks of life.… Their numbers dwindled down to only (seven) souls in 1820. Their names were: Mrs Elizabeth Farbessian, Mrs Maishkhanoom Avietian, Mrs Mariam Vardanian, Stephen Petrus, Minas Margarian, Gregore Agahian and Arrathoon Balthazarian, the only well-to-do amongst them being the lady mentioned first.”

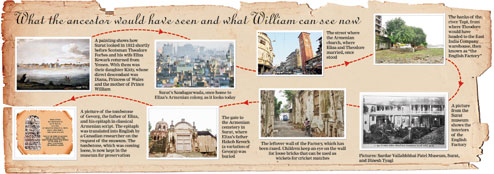

The warehouse

Jahnubhai Patel, who runs a zari business in the area, does not remember any Armenians but says his ancestors bought the home-cum-warehouse he owns from a Parsi businessman.

“There were many Parsis here then. The English Factory (a former East India Company warehouse-cum-house where Forbes once worked and lived) down the road was also owned by a Parsi businessman called Cooper who bought it from the British,” Patel said.

“We know this because his last descendant, who lived in the massive building all alone in the 1960s, was insane and broke down the place using a bulldozer as he was tired of researchers from India and abroad coming to his place regularly and requesting a tour of the premises,” recounts Patel.

Meghani confirmed the building’s razing by its “insane” owner.

“Prince William better come and collect the remaining bricks on this half-wall of the English Factory before the children of the adjoining I.P. Mission school take them away to use them as wickets in cricket matches on the school compound,” he said.

Called Saudagarwada even today, the area’s architectural character has largely changed, but demographically it still remains a predominantly merchant colony like it was when Forbes landed on the banks of the Tapi in 1809.

“As a young officer of the East India Company, he would have sailed in a boat down the Tapi from Suvalli, a British jetty near Surat, and landed on the riverbanks in the old city,” Mahida said.

The warehouse of the East India Company, where Forbes would have worked while in Surat, is a few furlongs from the Tapi’s banks. Today, destitute people and immigrant workers catch their afternoon nap on the river embankment by the English Factory, as the warehouse was called.

When The Telegraph visited the place, only a 12ft by 20ft, moss-laden, rundown wall of the “factory” stood. The remnants were in effect no more than a temporary boundary wall for an under-construction residential high-rise coming up where the warehouse once stood. Nothing else of it remains.

In Forbes’s time, the “factory” or warehouse was a two-storey structure of bricks and timber, said Meghani, quoting from a research paper on East India Company factories and facilities in Surat by Kyoto University’s Haneda Masashi.

“Masashi based his research on old Surat Municipal Corporation records before most of them were destroyed in a flood in 2006,” Meghani said.

While the ground floor was used as a godown, Forbes would have lived in the comfortable staff quarters on the first floor.

About 500 yards down the same street would have stood the warehouses of other European merchant companies, owned by the Portuguese, Dutch and the French. The Armenian settlement where Eliza would have lived began after that and the Armenian church would have been down the same street.

“The entire area would have had a radius of one kilometre. It would have been bordered by gardens, fountains and a red-light district from the Mughal era that existed in the old city till about a decade ago. Saudagarwada would have been a bustling place,” Meghani said.

Indian-Armenian marriages

The Telegraph, June 21, 2013

Meghani said that marriages between Armenian men and Indian women were uncommon but not unheard-of around the end of the 18th century.

“The community had been settled in India for over 500 years by then and was seen as close to the Mughal throne and hence powerful. So, intermarriages would not have been terribly frowned upon,” Meghani said.

The romance

In such a “happening” place, buzzing with pretty local girls and dashing merchants and sailors, the romance of Forbes and Eliza would have blossomed.

“And for what it is worth, the relationship seems to have been more than a bond of convenience,” Meghani suggested.

Despite the accepted norm of keeping mistresses, did the 23-year-old Forbes love a 19-year-old Eliza enough to make her his wife? “It seems he tried,” Meghani said.

“If British researchers say he may have married her in the Armenian church, it would have been a very honourable thing to do given that if he had not, no one would have raised a finger,” Meghani said.

According to the records, Forbes, when posted to Yemen soon after, took Eliza, pregnant with his daughter, along.

“When the child was delivered in Yemen, he named her Kitty after his mother. By the time Eliza and Forbes returned to Surat, they had had another baby, Alexander. Later, she delivered another son, Fraser, who died after six months,” Meghani said.

“Although Forbes neglected the family after moving to Bombay, he did send a close friend, Thomas Fraser, another Scotsman, to look up Eliza in Surat. It was on Fraser’s suggestion that he sent Kitty to Scotland. He even mentioned his children and Eliza in his will. Does not seem like a scoundrel to me,” said Meghani.

No Armenian population in Surat: 2013

The Telegraph, June 21, 2013

Samyabrata Ray Goswami

On the elusive trail of Eliza Kewark

Prince William need not come knocking to Surat; his folks do not live here any more. The genetic needle that threaded his DNA to an Indian ancestor is more or less lost in the haystack of history.

But if he takes a stroll around the old city, perhaps among the oldest cosmopolitan pre-British urban centres in India, he might pick up a few old threads to spin a yarn about his multi-cultural genealogy.

There are no Armenians in Surat any more. Residents of the old city, largely small-scale textile traders, have long bought over their properties and razed them to build newer houses and trading markets.

But it is in the alleys of old Surat’s Saudagarwada (borough of merchants) that his mother’s Indian-Armenian ancestor, Eliza Kewark, lived a lonely life after her Scottish husband deserted her and died aboard a ship on his way back home to Aberdeenshire.

William’s mother Diana was a direct descendant of Kitty, daughter of Eliza and Scotsman Theodore Forbes.

See also

Armenians in India