Asaf-Ud-Doulah

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

This article was written in 1939 and has been extracted from

HISTORIC LUCKNOW

By SIDNEY HAY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ENVER AHMED

With an Introduction by

THE RIGHT HON. LORD HAILEY,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E.

Sometime Governor of the United Provinces

Asian Educational Services, 1939.

Asaf-Ud-Doulah

1775-1798

Asaf-Ud-Doulah Is Remembered to this day in Lucknow for his unlimited generosity. When Shuja-ud-Doulah died in 1775, his son Mirza Amani became Nawab, assuming the name of Asaf-ud-Doulah. In the same year, he transferred his capital from Fyzabad to Lucknow and at once set on foot schemes for the aggrandisement of his new headquarters, for Lucknow was then not much more than a large village. He and his courtiers lived in the Daulat Khana behind the Taluqdars’ Hall in the Husainabad area while his other schemes were taking shape.

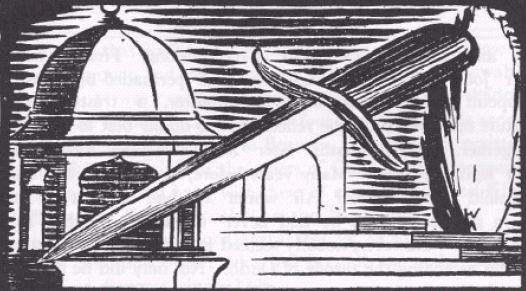

To him are attributed the Rumi Darwaza, the Great Imambara and the Bibiapur Kothi. The magnificence and wealth of his court enhanced his fame until it exceeded that of the Great Mogul himself, living not so far away at Delhi. Adventurers, hearing of the riches and luxury to be had almost for the asking, crowded to the court of Lucknow.

During this reign the fame and luxury of Oudh reached its zenith. No other kingdom throughout the length and breadth of India could rival it. The Nawab’s only apparent ambition was to discover how many elephants the Nizam or Tippu Sultan possessed, how valuable were their diamonds—and then to surpass them. His vast wealth was collected from the peasants who were fleeced by officials until they were put almost out of existence. Six months after his accession Asaf-ud-Doulah ceded Jaunpur and Ghazipur to the British with an annual payment to the Company.

He then applied for, and received, the services of several Europeans to officer his troops. Shortly after they had assumed command of the army a mutiny broke out and a fierce engagement was fought between 2,500 matchlockmen and 15,000 regulars. This only ended when a tumbril exploded and the rebel forces retreated, leaving 600 mutineers and 300 regulars dead on the battle-field.

Asaf-ud-Doulah heard of an enterprising young Frenchman named Claud Martin, whose inventive mind had, amongst other things, caused the first balloon in India to ascend into the air. This intrigued the Nawab who asked that Martin might be transferred to his service. The request was granted. From that time began Martin’s days of wealth., prosperity, and power. When he came to Lucknow he took over the Hayat Baksh Kothi, the present Government House, as an arsenal. There he established “a manufactory where he makes pistols and fusils both as to lock and barrel better than the best arms that come from Europe.” He was clever and a faithful servant to the Nawab, and effected many excellent reforms in the military machinery of the state.

Portraits show Asaf-ud-Doulah as a squarely built man of portly mien, with protruding eyes and pendulous moustaches. His dress, of the finest white muslin, reached to his instep and was very full, bordered by rich metal braid. Long sleeves were caught at wrist and upper arm by bands of embroidery. His closely wound turban was overlaid with plaques of precious stones, surmounted by valuable aigrettes. About his waist wound a thick scarlet-and-gold cord into which was thrust a large jewelled dagger.

When the fame of the Court of Oudh was firmly established an English artist named William Hodges, who had been a member of Captain Cook’s expedition to the South Seas, visited India, where he secured the patronage of Warren Hastings. In company with another artist, John Zoffany, who was then coming to the end of his monetary resources in England, and who had obviously been stirred by the extravagant tales of wealth at the court of Oudh, Hodges set sail in 1783.

The two artists landed at Calcutta, whence they made their way upcountry to Lucknow. Hodges did not make much headway but Zoffany quickly established a reputation for himself, and in 1784 he painted a portrait of the Nawab, inscribed: “John Zoffany painted this picture at Lucknow A.D. 1784 by order of His Highness the Nawab Vizier Asoph-ud-doulah, who gave it to his servant Francis Baladon Thomas.” Zoffany immortalised a favourite sport of the day in what is, perhaps, his best-known picture, ‘Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match’, painted in 1786.

In this picture appears a portrait of the Nawab and of other well-known contemporaries, both Indian and European. During Asaf-ud-Doulah’s reign seven British Residents successively assisted in the administration of his lands and revenue. In 1794 one Thomas Twining of the Civil Service accompanied the Commander-in-Chief of the Company’s army on a tour of inspection. On January 5, 1795, Twining wrote: “I dined to-day with Mr. Orr, an English merchant, and met a large party of English gentlemen, among whom was Dr. James Laird, brother of the head physician who accompanied Sir Robert Abercrombie from Calcutta. There were also Mr. Paul and Mr. and Mrs. Arnot. Mrs. Arnot enjoys the distinction of being the handsomest lady in India.”

Mr. Orr was a rich merchant who resided for many years in Lucknow, besides possessing a bungalow at Tanda near Fyzabad, where also were situated one of his several cotton cloth factories. Twining was agreeably impressed with Lucknow society for he wrote that “the style in which this remote colony lived was surprising, it far exceeding even the expense and luxuriousness of Calcutta. As it was the custom of these families to dine alternately with each other they had established a numerous band of musicians.”

Of the Nawab himself, Twining noted that “in polished and agreeable manners, in public magnificence, in private generosity, and also, it must be allowed, in wasteful profusion, Asafud- Doulah, Nawab of Oudh, might probably be compared with the most splendid sovereign of Europe.”

The Nawab had a great admiration for things European and things mechanical. In a building known as the Ina Khana he made a collection of objects which, so long as they were English, needed no other common denominator. Watches, clocks, scientific instruments, firearms, glass, and furniture were jumbled together in utter confusion.

Timepieces studded with jewels and exquisitely ornamented in coloured enamels lay cheek by jowl with the most tawdry imitations. Each had probably cost the Nawab an equal sum of money, and each had presumably caught his attention for a similar number of minutes. Above this quaint muddle of trumpery and jewels hung a myriad crystal prisms, reflecting the light diffused from a number of wall and table lamps set here and there with little thought of artistry.

In 1784 a famine came upon Lucknow. As a relief measure and to give employment to his people, Asaf-ud-Doulah caused architects throughout India to submit plans for a building to be known as the Great Imambara.

But the Nawab, although he built great palaces, laid out beautiful gardens and sank wells, had no eye for the squalor of his immediate surroundings. The city itself was a miserable place; the streets were narrow, dirty, and crowded with bazaars and very poor people. “It was evident,” writes one spectator, “that splendour was confined to the palace while misery pervaded the streets: the true image of despotism.”

In spite of this the Nawab was held in affection by his subjects until the day of his death and was laid to rest beneath the high vaulted ceiling of the Great Imambara, for which, rumour has it, over a million English pounds bought the ornate chandeliers and mirrors to complete the state’s bankruptcy.

As a result of extravagance and lack of supervision over petty court officials and taxcollectors, the court of Oudh found itself almost penniless at the death of Asaf-ud-Doulah in 1798.