Elections in India: behaviour and trends (historical)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Sources include

One MP for 16,00,000 voters

Mind the gap: 1 MP for 16L voters

Keeping In Touch With Electors Tough

Subodh Varma | TIG

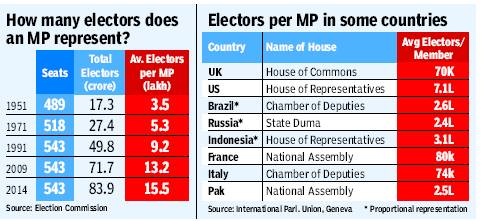

For the 2014 general elections, over 84 crore/ 840 million people are registered as voters as per the latest Election Commission figures. They will elect 543 MPs. That means on average, each MP represents over 15.5 lakh voters. That’s almost four and a half times the number of voters per MP in the first general elections held in 1951-52.

Voters have been increasing because population is increasing. But the number of seats in Lok Sabha has not increased since 1977. As a result, an MP has to represent more and more people with each passing election.

This anomaly gets stranger if you look at statewise averages of voters per MP. For the coming election, a Rajasthan MP will represent nearly 18 lakh voters on average, while one from Kerala will represent just 12 lakh voters. This is among the bigger states, not counting the smaller states and UTs where MPs can get elected with as low an electorate as 50,000 as in Lakshadweep or four to eight lakh in the Northeast.

In the 2008 delimitation, standardization of constituencies did not take place as it would have meant creating more constituencies in states like Rajasthan or Bihar with higher population growth rates, and cutting down in states like Tamil Nadu or Kerala with lower population growth, says election expert Sanjay Kumar, director of New Delhi-based think tank Centre for Studies of Developing Societies.

“It would have meant penalizing states that have successfully restricted their population. This was not fair,” he explained.

So, constituency numbers were kept the same within states, leading to the present anomalous ratio of voters per MP. Nowhere in the world is there such a high ratio of voters per elected representative. The closest would be the US where the average number of voters per House of Representatives member is about 7 lakh.

All this leads to an increasing disconnect between people and elected representatives, turning serious as elections approach. In two weeks candidates have to somehow contact 15 lakh people. With increasing restrictions on overt spending – on posters, vehicles or public meetings – the dynamic of contesting elections is fast changing. And so is covert spending. Increasing use of electronic media or Web-based platforms is also driven by this compulsion.

Once the MP is elected, the responsibility of staying in touch with the voters also is more difficult.

Although the MP is not supposed to be looking after day-to-day issues like roads or drinking water or whether doctors are there in health centres, in India’s topsy turvy democracy it doesn’t work like that.

“People expect their elected representatives to solve everything. They don’t make a distinction between what an MP is responsible for and what a local councillor is supposed to do,” says Kumar.

In reality, the elected representatives too don’t follow these distinctions when it comes to promises, so the people can’t be blamed.

So, what is the solution? In the future, there is no option but to increase the number of seats in the Parliament opines Kumar. But for now, the unwieldy electoral system will have to bumble along.

Candidates elected by at least 50% of the voters

Only 120 winning candidates in ’09 got over 50% votes

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

New Delhi: Is our democracy truly representative? Election Commission (EC) data on percentage of votes secured by winning candidates shows it may not be so. In the 2009 general elections, only 120 winning candidates out of the 543 could secure 50% or more votes polled in their respective constituencies.

This meant that on remaining 423 seats (nearly 78% of seats), the winning candidates had the approval of less than half of the electorate. Elections to the Lok Sabha are carried out using the first-past-the-post electoral system, in which the candidate securing the maximum votes of the total votes polled is declared elected, irrespective of the percentage of votes polled or the total number of eligible voters.

The EC data has a silver lining though. Delhi, Rajasthan, West Bengal, Kerala, Gujarat and Maharashtra are some of the better states in terms of consolidation of votes in the favour of winning candidates. While Delhi had six out of seven candidates winning more than 50% votes, Rajasthan was second best with 15 of the 25 winning candidates in that category.

Half of the 42 winning candidates in West Bengal secured the approval of more than 50% of the electorate. Among the worst performing states is Andhra Pradesh where only one out of 42 candidates could get more than 50% votes polled.

DELHI TOPS

Delhi first in vote consolidation, Rajasthan second

Half of the 42 winning candidates in Bengal got over 50% votes

Andhra the worst with only one out of 42 getting over 50% votes

Corruption does not bother the voter

Is graft really a big election issue? Stats say otherwise

Deeptiman Tiwary TNN

New Delhi: Is corruption really an issue in elections? Some surveys claim people worry more about the economy than corruption. Data for 2004 and 2009 general elections show that not only do parties continue to repeatedly field candidates facing graft charges, people even vote for them.

Analysis of affidavits filed by Lok Sabha candidates shows that in 2004, parties fielded a total of 12 candidates facing cases under Prevention of Corruption Act (PCA). Of them, nine won. In 2009, 15 candidates with PCA cases were in the fray with four emerging victorious. Both elections combined, 27 such candidates contested and 16 of them won — a success rate of almost 60%.

Data also shows only one of 2004’s winners (SP’s Rashid Masood) with graft cases lost in 2009. Of the nine winners in 2004, only three (including SAD’s Rattan Singh and RJD chief Lalu Prasad) contested in 2009. Among other winners of 2004, BSP chief Mayawati was UP CM at the time of the 2009 polls and SAD’s Sukhbir Singh Badal was Punjab deputy CM. One candidate died while others did not contest.

A recent survey by Lok Foundation and University of Pennsylvania’s Centre for Advanced Study of India says corruption has found some traction with voters this election, but is still at second position compared to economic growth.

Social and political theorist and Centre for the Study of Developing Societies professor Aditya Nigam says though people seemed to have accepted graft as a part of life until recently, this election could be different. “Giving bribes at every step for decades had made people accept corruption as their destiny. But the Anna Hazare-led anti-corruption movement and Arvind Kejriwal’s AAP have changed that feeling. Economic growth is too abstract an idea to attract masses unless someone breaks it down for them.”