Unsettled tribes: Sholapur

Contents |

Unsettled tribes: Sholapur

This is an extract from a British Raj gazetteer pertaining to Sholapur that seems |

Unsettled tribes

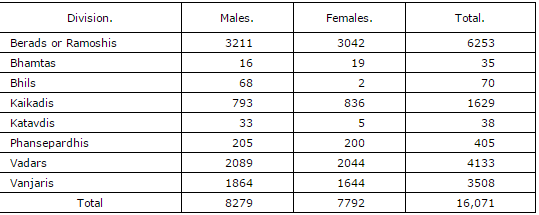

Unsettled Tribes include eight classes with a strength of 16,071 or 2.9 per cent of the Hindu population. The details are:

Berads

Berads, or Bedars, are returned as numbering 6253 and as found over the whole district. Like Mhars Mangs and others who serve as village watchmen Berads are sometimes called and sometimes call themselves Bamoshis. They are divided into Berads and Helgas who neither eat together nor intermarry. They are dark and either stout or strongly made. The men keep the topknot and the moustache but not the beard. They speak Marathi with others and among themselves a dialect of their own. Some are wanderers, living in forests and waste lands and others who are stationary live in shabby grass huts. A few own houses of mud and stone walls with flat or thatched roofs. Their house goods include a few metal vessels and a few own bullocks. Men women and children eat sitting together out of the same dish. Their staple food includes jvari bread, vegetables, and pulse. They are excessively fond of country spirits. The men dress in a waistcloth or a pair of drawers reaching to the knee, a long coat with sleeves, a shouldercloth, and a turban. The women dress in a robe and bodice, and the boys in a loin and shouldercloth. They have a set of better clothes for great occasions. Their women's ornaments are the same as those worn by cultivating Marathas. They are idle, hot-tempered, and impudent. Their most binding oath is taken on bhandar or turmeric. Their main calling is village watching, and they carry a sword, shield, and matchlock. Some are husbandmen and others labourers. Their women work as labourers, spin cotton, and sell fuel and grass. They are poorly paid, have no credit, and live from hand to mouth. The chief objects of their worship are Ambabai, Jotiba, and Khandoba, and their priests are the village Brahmans. A woman is impure for ten days after childbirth. On the fifth the house is cowdunged, balls and millet or wheat flour biscuits are made and offered to Satvai, and in the evening a feast is held. The babe if a boy is named on the thirteenth, and if a girl on the twelfth. On the naming day women guests cradle the child and rock it, singing songs. When the singing is over they are given wheat and jvari and their hands and faces are rubbed with turmeric powder; near relations present the child with new clothes, and the guests retire. If the child is a boy its hair is clipped when it is six or twelve months old. Betrothal among them is the same as among cultivating Marathas. A day before the marriage booths are raised at the houses both of the boy and of the girl, the marriage guardian or devak consisting of leaves of five trees or panchpalvis is worshipped, a sheep is offered, at night a feast is held, and the boy and girl are rubbed with turmeric at their own houses. On the marriage day the guests are feasted at the girl's, the couple are presented with clothes and ornaments, and made to stand on an earthen platform or ota and a curtain is held between them. A Brahman, who acts as priest repeats verses, rice is thrown over their heads and they are husband and wife. A piece of yellow thread, twisted into seven or nine folds, is tied with a piece of turmeric to the wrists both of the boy and the girl. A cloth is spread on a wooden stool, rice is heaped on the cloth, and a metal waterpot is set on the rice heap and worshipped. After feasting for a couple of days on the fourth the boy and girl are seated on a bullock and go in procession round the village to the boy's house. After a stay ota week or so the girl returns, on the fifth of the next Shravan comes the ceremony ofvavsa or home-taking when the boy's kinsfolk carry to the girl's a present of a robe and bodice, wheat flour, molasses, turmeric, redpowder, and betel. At the girl's they are feasted and carry the girl back to the boy's, and after a stay of a few days she is taken back by her father's relations. The same ceremony is repeated on Sankrant Day in January, when, if the girl's parents are well-to-do, they send the boy a present of a turban and some clothes for his relations. When a girl comes of age, she is seated by herself for four days, and, in the morning of the fifth, she is bathed and presented with a new robe and bodice. They allow widow marriage and practise polygamy. Their funeral ceremonies are the same as those of cultivating Marathas. Their headman called naik or leader settles all social disputes. Berads do not send their boys to school nor take to new pursuits. They are a very poor class.

Bhamtas

Bha'mta's, [Details of the Bhamta customs are given in the Poona Statistical Account.]or Pickpockets, are returned as numbering thirty and, except one male in Madha, as found solely in Barsi. They look like high caste Hindus, and speak a mixture of Hindustani Gujarati and Marathi. Their dwellings are the same as Maratha houses either wattle or daub huts or houses with mud and stone walls and thatched roofs. Both men and women dress like high caste Hindus, the women drawing the upper end of the robe over the head and the skirt back between the feet. They have the same rules about food as Marathas, eating the flesh of sheep, goats, fowls, hare, and deer, and eggs, and drinking liquor. When they start on a thieving expedition either in gangs or singly the men dress in silk-bordered waistcloths and shouldercloths, coats, coloured waistcoats, and big newly-dyed turbans with large gold ends dangling down their backs and folded either in Maratha or Brahman fashion. Both men and women are petty thieves and pickpockets, and steal only between sunrise and sunset. They are under the eye of the police and those who are well known to the police and are aged give up picking pockets and settle as husbandmen. They complain that the number of non-Bhamta pilferers is growing and that their competition has reduced their profits. Still as a class they are well-to-do.

Bhils

Bhils. The 1881 census showed seventy Bhils in Madha and Karmala. They were probably outside beggars or labourers. It is said that no Bhils are settled in the district.

Kaikadis

Kaika'dis are returned as numbering 1629, and as found in towns and large villages. They are divided into Jadhavs and Manes, who eat together but do not intermarry. They speak Marathi with a mixture of other words. [Among the non-Marathi words are, Rati forbhakar bread, telni for pani water, pal for dudh milk, tal for dhanya grain, gomda for gahuwheat, seja for bajri millet, yersi for tandul rice, mor for dahi curds, nai for tup clarified butter, shakri for salchar sugar, balle for gul molasses, to for de give, ita for nahi no, ba forye come, ho for ja go, od for dhav run, and nankot mi duila, for maj javal kahi nahi I have got nothing with me.] Their settled dwellings are of mud and stone, and they have metal and clay vessels. They keep cattle and donkeys as well as dogs. During their travelling season, that is from October to May, they live in mat huts set on bamboo poles, which as they move from place to place they carry with their house goods on the backs of donkeys, bullocks, or buffaloes. They are hereditary thieves and robbers and are always under the eye of the police. They eat pork, sheep, and goats, and drink liquor. Their staple food includes millet orjondhla and split pulse, and on holidays they prepare cakes and rice. The men dress like Marathas in a waistcloth, waistcoat, and tattered headdress; and their women in the robe and bodice. They are dirty, cruel, and given to thieving. They make the reed sizing-brushes which are used by weavers, they also make snares for catching birds and deer, and their women plait baskets of the branches leaf fibres and stalks of the tarvad Cassia auriculata tree. They plait twigs of the same material into wicker work, and cages for storing grain, and sell them and beg at the same time. Some have lately taken to tillage. Their favourite deities are Bhavani, Khandoba, Narsoba, and Vithoba, and their priests are the ordinary Brahmans. Their women are impure for twelve days after childbirth. On the fifth day two silver images or taks, some fruit, and a dough cake or mutka are laid in a winnowing fan and worshipped by the mother. If the child is a boy the caste is feasted, and the images are hung round the neck of the child and its mother. On the twelfth the child is laid in a twig cradle and named, the name being given by the village Brahman. When the child is a year or two years old its hair is clipped. Their wedding guardian or devak is the mango and the umbar Ficus glomerata twigs of which they bring home, worship, and, offering a sheep, feast the caste at least a couple of days before the marriage. They either burn or bury the dead. The four corpse-bearers are held impure for five days, and are not only avoided by others but do not even touch each other. Except the chief mourner who is held impure for five days the other members of the family mourn for three days only. On the fifth day a nimb Azadirachta indica branch is dipped in cow's urine, the head of the chief mourner is touched with it, and he is shaved by the barber, as are the heads of the four corpse-bearers, and their shoulders are rubbed with sweet oil. They feast the caste both on the third and on the fifth. They make an image or tak of the dead, set it in the family shrine with the other gods, and worship it onDasara in September-October and on Divali in October-November. They allow widow marriage, the widow during the ceremony being seated on a bullock's saddle. A caste council or panch settles social disputes. A few send their boys to school, but on the whole they are a wretched class.

Katkaris

Ka'tavdis or Ka'tkaris, that is Catechu-makers, are returned as numbering thirty-eight men and as found in Madha only. They are not permanent residents of the district but occasionally come during the fair weather from below the Ghats in search of work, especially the picking of groundnuts and return to their homes before the rains.

Phansepardhis

Pha'nsepa'rdhis, or Snarers, are returned as numbering 405 and as found wandering over the district. They are a low unsettled tribe. The men do not shave the head, and let the beard moustache and whiskers grow. They speak a mixture of Gujarati Marathi Kanarese and Hindustani, but their home tongue is Gujarati. They generally live in huts outside of the village and keep cows, buffaloes, sheep, and donkeys. Their food includes jvari, split pulse, and vegetables, and they eat fish and flesh and drink liquor. The men dress in short drawers, a tattered turban, and short shouldercloth with which they often cover their bodies. The women dress in a robe and out of doors put on a bodice which generally reaches to the waist. They wear ear, nose, neck, hand, and foot ornaments generally of bellmetal and brass. They are a strong, hot-tempered, and cruel people. They are hunters and snarers and are very skilful in making horsehair nooses in which they catch almost all birds and some animals. They prepare and sell cotton cakes and sell fuel. A few are husbandmen and watchmen and the rest work as day labourers and beg. Their favourite deities are Ambabhavani, Jarimari, Khandoba, and all other village gods, and their chief holidays areShimga in February-March and Dasara in October-November. Among them betrothal takes place a day to a year or two before marriage. At the betrothal the girl is presented by the boy's father with a robe and bodice and her brow is marked with redpowder. The headman of the caste must be present at the ceremony, he is given a sum of not more than 6s. (Rs. 3), and the castefellows are treated to a full supply of liquor. On the marriage day the boy and girl are made to stand side by side, the hems of their garments are tied together by seven knots, a white sheet is held over their heads, and the village Brahman repeats verses. At the end he throws rice over their heads and the boy and girl are husband and wife. The Brahman retires with a money present, the caste is feasted with split pulse and wheat cakes both by the boy's and the girl's fathers, and the marriage ends by the boy taking the girl to his house. They have a headman called naik or leader, and settle social disputes at caste meetings. A person accused of adultery or other grievous sin is told to pick a copper coin out of a jar of boiling oil. If he picks the coin out without harming his hand he is declared innocent; if he refuses to put his hand into the jar, or if in putting it in his hand is burnt, he is turned out of caste and is not allowed to come back. The Phansepardhis do not send their boys to school. They are under the eye of the police and are a depressed people.

Vadars

Vada'rs are returned as numbering 4133 and as found scattered over the district. They are divided into Gada or Cart Vadars, Mati or Earth Vadars, and Pathrat or Stone Vadars, who eat together and intermarry. Cart Vadars take their name from their low solid-wheeled stone carrying carts, Earth Vadars because they do earth work, and Stone Vadars because they quarry and dress the stone. They are dark, tall, and regular-featured, the men wear a topknot, whiskers, and moustache, but not the beard. Boys up to twelve or thirteen wear ear knots. Their home tongue is Telugu, but with others they speak Marathi. They live outside of villages in mud and stone houses with flat roofs, and some in huts of cane or mats of long stiff grass or pansar. Their houses are filthy, and are surrounded by pigs, donkeys, fowls, cattle, dogs, and buffaloes. Their staple food is jvari, vegetables, and pounded chillies, and when they can afford it, they eat the flesh of sheep, goats, fowls, hogs, and rats of which they are specially fond. They drink liquor but do not eat beef. They keep from animal food on Fridays Saturdays and Mondays in honour of their gods Narsoba and Vyankoba. Their dress is like that of other low caste Hindus. The men wear a coarse white turban or scarf, a shoulder-cloth, short trousers reaching to the knee, and a jacket. They wear sandals and forbid shoes so strictly that any one who wears shoes is put out of caste and is not allowed to come back. Their women wear the robe but not the bodice. They have glass bangles on the left wrist, and tin brass or silver bangles on the right wrist, and they wear nose and ear rings, necklaces, wristlets, and false hair. The younger women deck their heads with flowers. As a class Vadars are hardworking, thrifty, hospitable, and orderly, but rude, drunken, hot-tempered, and of unsettled habits. The Gada or Cart Vadars carry building stone either in low solid-wheeled carts or on donkeys. The Mati or Earth Vadars dig ponds and wells and make field banks. The Pathrat or Stone Vadars cut and make grindstones, quarry, and work as masons. They are also known as Gavandis. They make stone images of gods and animals and cups, which are bought by pilgrims at Pandharpur. The three classes keep to their hereditary calling. They say they do not wish to snatch another's bread and put it into their own mouths. They work as field labourers and sometimes beg. Children, as soon as they are old enough, help the men in their work but the women generally do nothing but mind the house. They are one of the hardest working classes in the Deccan, working in gangs almost always by the piece. Their services have been of the greatest value in the great water and railway works which have been pushed forward in the Deccan during the last ten years. They have worked hard and earned high wages, but spent much of their earnings on liquor. High caste Hindus touch Vadars, and they hold aloof from Mhars, Mangs, and Chambhars, They worship the usual Hindu gods and goddesses, and their chief object of worship is Vyankoba of Giri or Tirupati in North Arkot. They worship Mariamma, Narsoba, Padmava, and Yallamma. Among their house gods are the images of their deceased ancestors, generally square flat metal plates with turned edges and a figure stamped on them. They worship them with the same rites as other Hindus, washing them, rubbing them with sandal, throwing flowers over them, burning incense before them, and offering them cooked food. They have no priests, but ask Brahmans to name their children and to fix a lucky day for their children's marriages. They keep the regular Hindu fasts and feasts. They make pilgrimages to Pandharpur, Tuljapur, and Vyankatgiri in North Arkot. They believe in sorcery witchcraft and soothsaying. They generally marry their boys after twenty and their girls -after sixteen. An unmarried girl who has a child is put out of caste and is not allowed to come back. They allow widow marriage and practise polygamy. They have no music at their marriages, exchange no presents of clothes, and do not rub the boy and girl with turmeric. They say they used to have music, presents, and turmeric, but gave them up because a man who was sent by one of their chiefs to buy clothes for a wedding on his way to the town saw by the roadside the lower half of a stone handmill. He lifted the stone and under it saw a beautiful naked girl the goddess Satvai. The girl told him to put back the stone. He was confused by her beauty, failed to obey, and was struck dead. The chief waited for a time and had to go on with the marriage without the presents. When the marriage was over they searched the country and found the dead man. Since, then they have never used turmeric music or presents. Vadars are bound together by a strong caste feeling and settle their social disputes at caste meetings. They do not send their boys to school. During the last three or four years they have enjoyed steady and highly paid work.

Vanjaris

Vanja'ris are returned as numbering 3508 and found in all sub-divisions. They are tall, dark, and rather goodlooking, and their women are healthy and well made. They speak Marathi somewhat mixed with Gujarati, and are an indolent class. They earn their living as day-labourers and field workers. They generally live in grass huts inside the village, and their staple food includes jvari bread, pulse, and vegetables. Some of the men eat the flesh of goats and sheep, and drink liquor, but the women touch neither liquor nor flesh. The men dress in a loincloth and waistcloth, a jacket, a scarf or turban, and shoes. They sometimes carry a blanket and throw a cloth over their shoulders both in front and behind. Their women wear the Maratha robe and bodice. They have silk and embroidered clothes in store which they wear on great days. Both men and women pass their time in the fields and their children go to the waste to graze cattle. Unlike other Hindus they use the cow as a beast of burden. On the fifth day after the birth of a child they worship the goddess Satvai and get a Brahman to name the child on any lucky day between the twelfth and the marriage day. They marry their children at any time between five and thirty but girls are generally married between twelve and twenty. Their marriage ceremony lasts five days and they rub the boy and girl with turmeric at their houses, at least couple of days before the marriage. Marriage halls are raised at both houses and kinspeople and castefellows are feasted. On the marriage day the boy, with kinspeople friends and music goes to the girl's on a bullock and they are married, the marriage verses being repeated by a village Brahman. Feasts are given at both houses and when the feasts are over the boy goes with his wife on a bullock to his house with kinspeople and music. They allow widow marriage and practise polygamy. They generally burn their dead, and mourn ten days, offer wheat cakes and balls to the crows, and purify themselves. The ceremony ends with a caste feast on the thirteenth. They worship Amba-bhavani, Mahadev, and Ramchandra, and also non-Brahmanic gods as Mariai, Mhasoba, and Vaghoba whom they generally fear. They keep the usual Hindu fasts and feasts, and there has been no recent change in their religious beliefs. They settle their social disputes at meetings of the castemen. They do not send their boys to school. They have not yet recovered their losses during the 1876 famine.