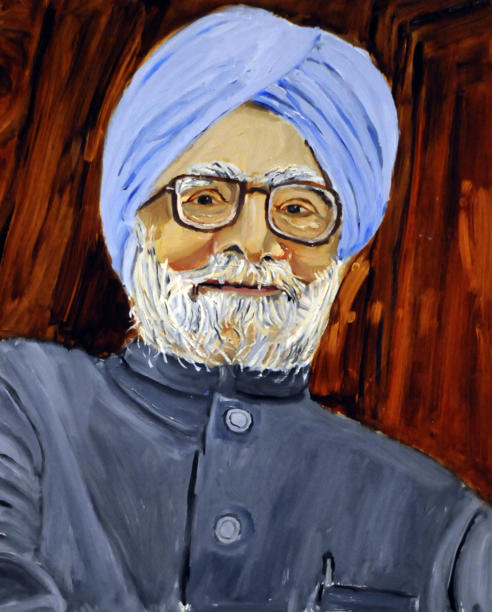

Dr Manmohan Singh

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content.

|

A timeline

He first made headlines as finance minister in 1991, but Manmohan Singh has been part of various governments’ core economic group much longer

The Times of India, Aug 28, 2011

INDIRA GANDHI (Cong)

Economic advisor, ministry of foreign trade (1971-72) Chief economic advisor, ministry of finance (1972-76) Director, RBI (1976-77)

MORARJI DESAI & CHARAN SINGH (Janata Party)

Director, RBI (1977-80) Secretary, dept of economic affairs, ministry of finance (1977–80)

INDIRA GANDHI (Cong)

Member-secretary, Planning Commission (1980-1982) Governor, RBI (1982–84) Member, Economic Advisory Council to the PM (1983-84)

RAJIV GANDHI (Cong)

Governor, RBI (1984–1985) President, Indian Economic Association (1985) Deputy chairman, Planning Commission (1985–87) Secretary-general and commissioner, South Commission, Geneva (1987-89)

V P SINGH (Janata Dal)

Secretary-general, South Commission, Geneva (1989-90)

CHANDRASHEKHAR (Samajwadi Janata Party)

Advisor to the PM on economic affairs (1990–91)

P V NARASIMHA RAO (Cong)

Union finance minister (1991–1996)

OTHER POSITIONS

Member, consultative committee for the ministry of finance (1996 onwards) Chairman, parliamentary standing committee on commerce (1996 -97) Member, committee on finance (1998 onwards).

Legacy

History will be kind to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh

Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar,TNN | May 15, 2014 The Times of India

History will be kind to Manmohan Singh. It will remember him as the finance minister who launched India's economic reforms in 1991, and the Prime Minister who presided over 8.5% GDP growth for most of a decade. It will also remember him as a Sikh who was nominated for Prime Ministership by a Christian Congres president and sworn in by a Muslim President in a country that is 82% Hindu.

[Indpaedia remembers him as the hugely successful economist sworn in by a scientist who was national icon, making India unique in an otherwise politicised world.]

Why will he not be remembered as the man under whom economic growth halved from 9% to 4.5%, inflation averaged almost 10% for five years, and unending scams culminated in the worst-ever electoral defeat for the Congres party? For the same reason that Abraham Lincoln is not remembered for scandalous dirty tricks and bribes to get his way (displayed memorably in the film 'Lincoln' ). Nor is Lincoln remembered as the hypocrite who won the election as a moderate on slavery, arguing that states had a constitutional right to slavery if they so wished, but then declared in 1863 that he had the power to abolish slavery by decree.

Few people know or care about Lincoln's failings: these pale beside his great achievement of abolishing slavery. Similarly, people will forget Manmohan Singh's failings, and remember him as the father of economic reform and superfast growth. This superfast growth persuaded George Bush to offer India a seat in the nuclear club, ending nuclear apartheid. It also persuaded Barack Obama to promise US support to India for a UN Security Council seat. These landmarks will remain in the history books long after the 2G scam is forgotten.

Set aside the history books: let's talk about today, as Singh demits office. Many critics complain that he didn't do enough in 10 years of rule. This criticism is mis-worded since it assumes that Singh has been ruling India, when the unquestioned ruler has been Sonia Gandhi. Formal democratic titles mean nothing in the semi-feudal ethos of the Congres Party. Only the dynasty matters.

This is a party where all members are supposed to sit up and beg when any member of the Gandhi family whistles. Its members have no rationale, purpose or hope of power save through the grace of the Gandhis. Dynastic feudalism is, of course evident in other parties too, like those of Lalu Prasad, Mulayam Singh Yadav, Deve Gowda, Jagan Reddy, Karunanidhi and sundry others. But the Congres has been the pioneer and greatest practitioner of feudal rule. The wazir in a feudal court has some powers, but must know his place in the power structure, or else lose his head.

Manmohan Singh was fully aware of and agreeable to this when he accepted the Prime Ministership. A seasoned bureaucrat, he was used to proposing ideas but retreating respectfully if opposed by his boss. He was ideal for Sonia, a respected technocrat with absolutely no political base or ambitions, who could serve but not threaten the dynasty.

This dynasty has generated more black money than all others combined. It found very useful Singh's unimpeachable reputation for integrity. This provided some cover to the dynasty when scams exploded. But it damaged Singh's own reputation. Remember the scene from the film 'Dabangg' where Malaika Arora dances in front of Salman Khan singing "Munni badnam hui, Darling tere liye?" This inspired a cartoon showing Manmohan Singh dancing in front of Sonia Gandhi, singing "Munna badnam hua, Darling tere liye."

In dynastic terms, Singh should perhaps be judged not as a Prime Minister but as a regent, keeping the throne warm for the young prince, under the watchful gaze of the Dowager Empress. I wrote back in 2005, after his first year as Prime Minister, that his approach could be summed up in Seven Commandments.

- Thou shalt not displease Sonia.

- Thou shalt not displease the Left Front.

- Thou shalt not test the limits of your powers.

- Thou shalt focus on surviving a full term.

- Thou shalt accommodate in the cabinet all criminals who can help this aim.

- Thou shalt at the end of your regency hand over the reins to the true dynastic inheritors.

- Thou shalt, meanwhile, be free to initiate policies that threaten neither the dynasty nor the coalition's survival (such as improving relations with Pakistan and China, and organizing buses to Muzaffarabad).

This was the story of UPA-1 until George Bush offered India membership of the nuclear club. Singh grabbed the offer, and Sonia gave her blessings. On this issue UPA-1 broke with the Left Front, risking defeat in Parliament. This courage paid off. But after victory seemed assured, Manmohan scored a terrible own-goal. He succumbed to opposition pressure by putting the liability for any nuclear mishap on foreign suppliers. Because of this, no nuclear power deals are going ahead at all. A great nuclear initiative has been nullified by cowardice on one clause.

The story of UPA-2 has eerie similarities, with Mamata Banerjee replacing the Left Front as the key force keeping the government alive, but extracting its pound of flesh . Sonia took economic growth for granted, did not listen to Singh's pleadings for further reforms, and switched to the NAC as her chief guide and mentor.

UPA-1 finally broke with the Left Front on the nuclear deal, and UPA-2 broke with Mamata after Moody's threatened to downgrade India's credit rating in 2012. This would have meant an immediate outflow of $100 billion, sinking the economy in the run-up to the 2014 elections. Drastic action was called for.

For the second time, Manmohan Singh took a firm stand and Sonia backed him. At the risk of losing Mamata's support and becoming a minority government, Sonia abandoned the NAC and allowed Singh and Chidambaram to chart a new course. They were asked to boost growth, tame inflation, and enact reforms.

Alas, they failed on all three counts. GDP growth remained at just 4.5%, half the 9% achieved earlier. Consumer price inflation simply did not fall below the 8-10 % range. As for reforms, the new rules for FDI in multi-brand retail were so loaded with cumbersome clauses that they have not yielded much investment. The subsidy on diesel was supposed to be phased out, but the crash in the rupee last year raised the import price, so the diesel subsidy today remains as high as ever. The Cabinet Committee on Investment cleared stuck projects worth Rs 6 lakh crore, yet this did not translate into any boom in orders for capital goods or construction contracts.

Why? Because a new licencepermit raj had come up unnoticed. The old licence raj was based on industrial licences, import licences and forex controls. The new licence raj was based on the environment, forests, tribal areas ad land acquisition. A veritable jungle of new controls in these areas was created at central and state levels. Initially, these new barriers were overcome by bribes. But once public anger exploded over corruption, clearances could not be bought, and the impenetrable nature of the new controls became evident. Judicial activism made bureaucrats wary of taking any decisions.

Singh and Chidambaram claim that things would have been much worse but for their efforts. Maybe, but that is hardly a winning election platform. For most of his 10 years, Singh was feted for his economic skills and integrity. He leaves office amidst economic travails and the smell of corruption.

Can he take solace in the fact that in his last six months, foreign money has flooded into India, the rupee has strengthened, and the stock markets have boomed. Alas, no. The sad fact is that they are booming because of the expectation that he will soon be replaced by Modi.

Singh started with two years of 8.5% growth and ended with two years of 4.5% growth. If only it had been the other way round! However, political careers rarely end on a cheerful note, as can be testified by his predecessors — Vajpayee, Gujral, Deve Gowda, Narasimha Rao, VP Singh, Rajiv Gandhi.

However, people are ultimately judged not by their failures but for their career achievements. Virender Sehwag, for instance, had to be ousted from the Indian cricket team after two years of bad performance, just like Singh. But the history books will record that Sehwag was India's highest scoring opening batsman ever. His later failures cannot eclipse his heroic feats in his glory days. The same will be true of Manmohan Singh.

A lacklustre second term

After bright start, PM faded away in 2nd term

The Times of India May 16 2014

Rajeev Deshpande New Delhi:

TNN

Singh Failed To Read The Writing On The Wall, Dithered On Reforms While Scams Derailed Economy

As a warm autumn sun shone benignly on a Cambridge lawn, the champagne being passed around seemed a perfect toast to the prime minister of India.

It was fitting that a ceremony to honour a former student with an honorary degree matched a growing recognition of India's rise as a nation, mentioned in the same breath as China.

In 2006, Manmohan Singh was coasting, his Cambridge laurel a small diversion, as he headed for an EU summit where his invocation of India as a $1 trillion investment opportunity sounded perfectly credible. As it turned out, the road thereafter got rockier. The 2008 India-US nuclear deal resulted in enormous turmoil. Singh won the day , but the victory was tainted by the cash-forvote scandal.

Yet, Congres won the 2009 Lok Sabha elections, brushing aside L K Advani's challenge. Singh did seem to recognize the need to nurture the gains, telling colleagues that the youth vote in particular tends to be impatient and volatile. He rightly felt that some credit for schemes like rural employment guarantee, farm loan waiver and Bharat Nirman was due to him and calculated he could push ahead with some of his pet agenda.

Looking back, Singh may have been better served if he had concentrated on the economy rather than engaging in risky foreign policy gambits like bettering ties with Pakistan. While the backlash to Sharm el-Sheikh rudely reminded Singh of the limits of his powers, he let slip an opportunity to tend to the economy at a time when the global climate was still fragile.

In mincing his steps, he failed to factor in the obvious: that three strong doses of financial stimulus had masked the impact of the global slowdown and much needed to be done to protect growth. So while the government dithered on reforms, Singh found himself battling the Commonwealth Games scam that broke in 2010. Around the same time, the 2G scam, with its roots in UPA-1, erupted in full force.

The honeymoon of his second term was over before it began.

The question whether things could have been handled differently is answered in Singh's lack of decisiveness in a crisis. The PM allowed senior ministers to convince him to let the 2G scandal play out in court, rather than examining solutions like cancelling the tainted contracts.

The argument that this would hurt business confidence and dent an economy under stress could be trumped by the much more urgent need to restore political credibility .

Singh chose the easier option, the economy worsened and BJP's graph rose. At a time when the economy needed his attention, Singh found Pranab Mukherjee as finance minister a handful, with officials recalling how Mukherjee's baritone dominated Cabinet meetings.

Constrained as he was by Congres chief Sonia Gandhi being the power behind the scene, Singh did not use what authority he could still wield. Being more assertive would have helped both him and Congres. Sadly for the PM, there is no clarity whether he did indeed try to cap the corruption scandals that corroded his legacy. There is little evidence to suggest he did so energetically .

The Commonwealth Games were saved only at the last minute. Coalgate ensured power projects stagnated while the mining sector slipped into negative growth, drowning out lakhs of jobs.

The scandals soon affected policy making as the government was pinned down by a tough auditor and a combative opposition.

As the stasis deepened, Singh became more and more besieged, though he took the position that the graft controversies were “party matter“ for which he could not be held accountable.

His leadership was wanting when Anna Hazare's agitation cramped the government. It took him days to address the nation after the Nirbhaya case even as Delhi's streets were awash with protests led by the very youth of whose impatience he had warned.

He had his foreign policy successes. On occasions, like when he apologized to Sikhs for the 1984 killings, he stood head and shoulders over other leaders.

But for all his innate decency ,a record free of the taint of corruption and his erudition, Singh ended his 10 years in office a somewhat discontented figure. He failed to see that not exercising authority is a poor option, irrespective of the circumstance.

The extent of his administrative autonomy

Sonia chose FM without consulting PM, gave instructions on key files’

Manmohan Had Little Hold Over Cabinet, Claims Book

TIMES NEWS NETWORK The Times of India

Freedom to choose cabinet, own principal aides

After the Congres’s electoral victory in 2009, PM Manmohan Singh made “the cardinal mistake of imagining the victory was his. Bit by bit, in the space of a few weeks he was defanged. He thought he could induct the ministers he wanted. Sonia nipped that hope in the bud by offering the finance portfolio to Pranab (Mukherjee), without even consulting him,” reveals a new book by Sanjaya Baru, who was media adviser to the PM in UPA-1. Singh had apparently been keen to appoint his principal economic adviser C Rangarajan, “the comrade with whom he had battled the balance of payments crisis of 1991-92”, as finance minister.

Singh had opposed A Raja’s induction in the Cabinet, but caved in after 24 hours

Indo-US nuclear deal

Baru claims that when it seemed the Congres would cave in to the Left on the nuclear deal with the US, a dejected Singh told a couple of confidants, “She (Sonia) has let me down.”

Manmohan Singh said, “She (Sonia) has let me down” over the India-US nuclear deal. Later, he offered to quit Singh told Sanjaya Baru he accepted “the party president is the centre of power” Congres made sure all credit for initiatives like NREGA went to the Gandhis

Interestingly, Baru claims that Sitaram Yechury was supportive of the amended version of the nuclear deal but was helpless in the face of Prakash Karat’s refusal to budge accept the deal. When the PM was informed that the Left would not back the agreement, he was furious.

Authority over his own Cabinet

The PM seemed to have had little authority over his own Cabinet. “No one in Singh’s council of ministers seemed to feel that he owed his position, rank or portfolio to him. The final word always was that of leaders of the parties constituting the UPA,” says the book.

According to Sanjaya Baru, former media adviser to the PM, Congres MPs “did not see loyalty to the PM as a political necessity, nor did Dr Singh seek loyalty in the way. Sonia and her aides sought it.”

It adds that Singh often faced challenges while dealing with senior Congres ministers like Arjun Singh, A K Antony and the “presumed PM-in-waiting” Pranab Mukherjee. “Each had a mind of his own and each was conscious of his political status and rank”.

According to Baru, Singh shared a good working equation with finance minister P Chidambaram in UPA-I. He would insist that Chidambaram sit with him and finalize the budget speech. In contrast, his relationship with Pranab Mukherjee was far more formal. Mukherjee would apparently not even show Singh the draft of the budget speech till he had finished writing it. When he was external affairs minister, he would also ‘forget’ to brief the PM on important meetings with US President George W Bush and then secretary of state Condoleezza Rice.

The book also claims that Singh had tried to resist the induction of DMK's A Raja well before the 2G scam became public knowledge. “But after asserting himself for a full twenty-four hours, (he) caved in to pressure from both his own party and the DMK.”

All important files were shown to Mrs Sonia Gandhi?

Baru claims that Pulok Chatterjee, who served in the PMO in UPA-1 and is now principal secretary to the PM, would have “regular, almost daily meetings with Sonia Gandhi in which he was said to brief her... and seek her instructions on the important files to be cleared by the PM.”

The silent PM

For years, Singh's stoic silence has made him the target of many unkind remarks. But the secrecy shrouding his functioning – and his relationship with Congres chief Sonia Gandhi – has now been breached by a man he had handpicked. While offering the job to Baru, Singh had requested him to be “his eyes and ears”.

Baru’s book, ‘The Accidental Prime Minister’ paints a picture of a PM who decided to “surrender” to the party boss and the UPA allies. According to Baru, Sonia’s “renunciation of power was more a political tactic than a response to a higher calling”.

Much of what Baru — who served between 2004 and 2008 — has written has been long heard on the Capital’s political grapevine, but this is the first time an insider has spilled the beans quite so candidly.

Two power centres: PM and Chairperson

On the question of a ‘diarchy’ or two power centres, Baru says there was no such confusion in Singh’s mind. He quotes Singh as having told him, “I have to accept that the party president is the centre of power. The government is answerable to the party.”

Baru claims that there was an eagerness to claim all social development programmes as the Sonia Gandhi-chaired National Advisory Council's initiatives, even though the Bharat Nirman programme came out of the PMO -- drafted by the late R Gopalakrishnan, who was joint secretary.

He also claims that on September 26, 2007 — Manmohan Singh's 75th birthday — Rahul Gandhi led a delegation of general secretaries to wish him. Rahul wanted to extend NREGA to all 500 rural districts in the country. Baru sent a text message to a journalist that this was the PM's birthday gift to the country. When he was summoned by the PM, he apparently told Singh, “You and Raghuvansh Prasad (then minister for rural development) deserve as much credit.” The PM snapped: “I do not want any credit for myself... Let them take all the credit. I don't need it. I am only doing my work.”

Wanting to resign

The book also reveals that Singh had threatened to quit if the UPA buckled under Left pressure and had told Sonia Gandhi to look for his replacement. Even as rumours circulated that Pranab Mukherjee or Sushil Kumar Shinde might be considered as his replacement, the NCP backed him, with Praful Patel telling Baru they would not support anyone but “Doctor Saheb”.

Sonia reportedly asked Montek Singh Ahluwalia, deputy chairman of the Planning Commission, to convince the PM not to resign. She also visited Singh at his residence with Pranab Mukherjee. The government was then allowed to proceed with the deal. However, such shows of resolve from Singh were not forthcoming in UPA-II. Baru cites his own case when the PM wanted to reappoint him as a secretary in the PMO in 2009. However, he had to drop the plan as he was told that the party was opposed to such a move. “To tell the truth, I was dismayed by the PM's display of spinelessness,” writes Baru.

The top officers of the Prime Minister’s Office

TKA NAIR

TKA NAIR WAS NOT SINGH’S FIRST CHOICE

(TKA) Nair was not Dr Singh’s first choice for the allimportant post of principal secretary. He had hoped to induct NN Vohra, who had given me the news of my job... Vohra even cancelled a scheduled visit to London to be able to join the PMO. Sonia Gandhi had another retired IAS officer, a Tamilian whose name I am not at liberty to disclose, in mind for the job. He had worked with Rajiv Gandhi and was regarded as a capable and honest official. However, he declined Sonia’s invitation to rejoin government on a matter of principle—he had promised his father that he would never seek a government job after retirement... Always impeccably attired, Nair, small-built and short, lacked the presence of Brajesh Mishra, whose striking demeanour commanded attention. He rarely gave expression to a clear or bold expression on file, always signing off with a ‘please discuss’ and preferring to give oral instructions to junior officials such as joint secretaries and deputy secretaries

MK Narayanan

PM WAS WARY OF NARAYANAN’S REPUTATION

Dr Singh too was wary of (MK) Narayanan’s reputation and would, on occasion, warn me to be cautious while carrying out sensitive assignments for him that he did not want anyone to know about

Pulok

PULOK INDUCTED INTO PMO AT SONIA’S BEHEST

Pulok, like Nair, suffered from the handicap that his own service had never regarded him as one of its bright sparks. A serving IAS officer, he had never worked in any important ministry... Pulok, who was inducted into the Manmohan Singh PMO at the behest of Sonia Gandhi, had regular, almost daily, meetings with Sonia at which he was said to brief her on the key policy issues of the day and seek her instructions on important files to be cleared by the PM

FIGHT BETWEEN MANI DIXIT AND MK

Mani and Narayanan, just two years apart in age, would often explode into angry arguments in the presence of the PM. On one occasion, Narayanan shouted at Mani: ‘You are a diplomat, who knows a lot about the world but knows nothing about India.’ Mani countered by asking Narayanan what he thought he knew about the country, considering he had never done ‘a good police officer’s job’...Dr Singh would sit through such altercations with a worried look. But on one occasion, it got bit too much for even a man as patient as him. While Mani and Narayanan were arguing vociferously in his presence, each accusing the other of overstepping his bounds, Dr Singh first kept quiet, then got up abruptly, looking visibly irritated

ON HOW ANU AGA WAS NOT MADE A PLAN PANEL MEMBER

The one name I was asked to sound out was Anu Aga, chairperson of Thermax. Her husband Rohinton Aga had been a contemporary of Dr Singh at college in England and she had distinguished herself as a corporate leader when she took charge of the family company after his death. When I called Anu, who was then in London, she asked for a day to consult her family. She called the next day and accepted Dr Singh’s invitation to join the Planning Commission. But when I went back to him with her acceptance, the PM looked sheepish and informed me that he had already agreed to appoint Syeda Hameed, a Muslim writer and social activist, and, so, I was told, there was no place left for Anu. I was left with the embarrassing task of explaining away the confusion to Anu... To my dismay, even Dr Singh seemed to take this embarrassment lightly

Narasimha Rao’s cremation

SONIA DIDN’T WANT RAO MEMORIAL IN DELHI

From Sanjaya Baru’s book:

I had very little to do with (Ahmed) Patel and during the few times we interacted he was always warm and friendly. I only had two substantive conversations with him during my time at the PMO. The first occurred shortly after Narasimha Rao died...Narasimha Rao’s children wanted the former PM to be cremated in Delhi, like other Congres Prime Ministers... However, Patel wanted me to encourage Narasimha Rao’s sons, Ranga and Prabhakar, and his daughter Vani to take their father’s body to Hyderabad for cremation. Clearly, it seemed to me, Sonia didn’t want a memorial for Rao anywhere in Delhi

Siachen

PM's ex-aide Sanjaya Baru blames ‘hawkish’ Antony, Army for scuttling Manmohan Singh's Siachen initiative, Gen JJ Singh hits back

Rajat Pandit,TNN | Apr 12, 2014

NEW DELHI: It's well-known that PM Manmohan Singh was very keen to convert Siachen into "a mountain of peace" after visiting the forbidding glacial heights in June 2005. But the Indian defence establishment was equally adamant that Pakistan would have to first authenticate the relative troop positions before any withdrawal from the Siachen Glacier-Saltoro Ridge.

Indian soldiers, after all, controlled almost all the dominating heights, ranging from 16,000 to 22,000-feet, on the Saltoro Ridge region. But with Pakistan unwilling to give ironclad guarantees on existing troop positions, the PM's dream slowly ebbed away and perished.

The PM's media adviser during UPA-I, Sanjaya Baru, has now set the cat among the pigeons by holding that Manmohan Singh's peace initiative for the world's highest and coldest battlefield was effectively torpedoed by the "hawkish" position of defence minister AK Antony, as also his predecessor Pranab Mukherjee, as well as the then Army chief General JJ Singh.

"I was never sure whether Antony's hawkish stance was because he genuinely disagreed with the Siachen initiative or whether he was merely toeing a Nehru-Gandhi family line that would not allow Dr Singh to be the one finally normalizing relations with Pakistan. After all, the Kashmir problem had its roots in Nehru's policies ... I felt Sonia would want to wait till Rahul became PM so that he could claim credit," writes Baru, in his new book "The Accidental Prime Minister".

Both Mukerjee and Antony, as successive defence ministers in UPA-I, were not enthusiastic about a deal on Siachen, though Sonia had "blessed"" the peace formula. Moreover, the PM also had to contend with "a declining quality" in military leadership. "In closed-door briefings, the general would say that a deal with Pakistan was doable, but in public he would back Antony when the defence minister chose not to back the PM," says Baru.

Gen Singh, who was the Army chief from 2005 to 2007 and Arunachal Pradesh governor till last year, hit back on Saturday. "What does he (Baru) know? What are his qualifications to pass such sweeping judgements and make disparaging statements on the military leadership? Does he have any idea what leadership is all about?" said Gen Singh, talking to TOI.

Dismissing Baru's knowledge of classified matters, Gen Singh said the military had given "perfectly sound advice" to the PM on the Siachen imbroglio. "We said unless Pakistan authenticates the troop positions, both on the ground and maps, there was no question of any withdrawal," the former Army chief said.

And even if Pakistan agreed to this pre-condition, the disengagement and demilitarization of the Siachen could only be done in a phased manner. "If Pakistan tried to indulge in some misadventure (to take the heights), the response and reaction time of our troops would have to be factored in. I am happy India's continues with the same stand," said Gen Singh.

Daman Singh on father Manmohan Singh

I

Manmohan is funny, gave nicknames to people: Daughter

Daman Singh charts the journey of her parents in her book "Strictly Personal: Manmohan and Gursharan".

Manmohan Singh had joined a pre-medical course as his father wanted him to become a doctor but pulled out after a couple of months, losing interest in the subject, according to a book on the former prime minister by his daughter.

Daman Singh charts the journey of her parents in her book "Strictly Personal: Manmohan and Gursharan", providing new insights into the couple but keeps away from the last 10 years when Singh was heading the UPA government.

She also finds her father to be a funny man saying he has a good sense of humour.

In April 1948, Singh was admitted to Khalsa College in Amritsar.

"Since his father wanted him to become a doctor, he joined the two-year FSc course that would lead to further studies in medicine. After just a couple of months, he dropped out. He had lost interest in becoming a doctor. In fact, he had also lost interest in studying science," Daman writes.

"I didn't have the time to think," the author, who based her book on conversations with her parents and hours spent in libraries and archives, quotes her father as saying.

"I went and joined my father in his shop. I didn't like that either, because I was not treated as an equal. I was treated as an inferior person who ran errands - bringing water, bringing tea. Then I thought I must go back to college. And I entered Hindu College in September 1948," Singh recalls.

Economics was a subject that appealed to him immediately. "I was always interested in issues of poverty, why some countries are poor, why others are rich. And I was told that economics is the subject which asks these questions," Singh tells his daughter.

While studying at Cambridge University, money was the only real problem that bothered Singh, the book, published by HarperCollins India, says.

"His tuition and living expenses came to about 600 pounds a year. The Panjab University scholarship gave him about 160 pounds. For the rest he had to depend on his father. Manmohan was careful to live very stingily. Subsidised meals in the dining hall were relatively cheap at two shillings sixpence," Daman writes.

Former PM Manmohan Singh with Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper. (Reuters file photo)

She says her father never ate out, and seldom indulged in beer or wine yet he would be in crisis if money from home fell short or did not arrive on time.

"When this happened, he skipped meals or got by on a sixpence bar of Cadbury's chocolate," she says.

He also asked a friend to lend him 25 pounds for two years but the friend could send only 3 pounds.

Daman found her father a very funny man. "When in a reflective mood, he sat with an index finger perched on the side of his nose. He was completely helpless about the house and could neither boil an egg, nor switch on the television."

He also had a sense of humour of sorts, she says. "This was evident when he was with friends, even if they were economists. It was comforting to know that he could laugh and crack jokes as well. With us, he rarely did either.

"The lighter side of him is that he liked to give nicknames to people. Unknown to them, one of our uncles was 'John Babu', another was 'Jewel Babu' and a third - to commemorate his pointed turban - was 'Chunj Waley'. My mother was 'Gurudev', and the three of us were 'Kick', Little Noan' and 'Little Ram'. Some of the other names he coined were less charitable," Daman writes.

According to the author, during his college years Singh read voraciously and the broad seep of his reading covered theological critique, social commentary and political ideology.

"Modern Punjabi literature was a special interest and he read in Gurmukhi as well as in Urdu."

Croquet was the most strenuous game he tried his hand at while he was at Cambridge.

He neither rowed nor punted. But he did watch a fair amount of cricket, particularly when Swaranjit Singh, a burly off-spinner who played cricket for the university team 'Light Blues', was on the field. In the company of friends, he would go for the occasional movie at the Arts Theatre, or else to a pub for the odd pint of beer, she says.

Daman says as a public servant, somewhere along the way her father retreated from family affairs and allowed his work to take over his life.

"Every day his office accompanied him home in big cloth bundles that we helped lug out of the car.

"He worked in bed where he sat cross-legged with a pillow on his lap, a stack of files beside him. As he hunched over his papers, inscribing neat squiggles, he would tug his beard and mutter to himself. When he was not working, he was usually preoccupied with a book or else with his thoughts," she says.

II

Dad faced a lot of resistance from within Congres, Manmohan Singh's daughter Daman says

Sagarika Ghose | Aug 5, 2014

At a time when Manmohan Singh's prime ministership has come under the scanner from the books of Sanjaya Baru and Natawar Singh, the former PM's daughter Daman Singh has sprung to her father's defence with her own book, "Strictly Personal, Manmohan and Gursharan". She says her father is not a manipulative politician or a wheeler-dealer.

In an exclusive interview with TOI ahead of the release of her book, Daman reveals many aspects of Manmohan Singh's life. Excerpts:

Manmohan Singh didn't believe in 2009 that Congres was going to win a second term

Daman: Yes he said that in a casual moment. I didn't probe it. But he said that no, no I don't think we are coming back. He seemed to believe so, although it was said in a light hearted way.

The relationship between Manmohan Singh and Narasimha Rao?

Daman: My father got a call from him and overnight he was the FM. He had a month to present the Budget. The economy was in a ghastly mess. Narasimha Rao made it all happen. Without him, my father could not have done anything. The ideas and radical approach came from my father, but it was Rao who made it politically feasible. My father always says it was a minority government that changed the course of India's entire economic policy. My father felt if he had five more years he could have done more.

My father says it is difficult to change things in India unless the system breaks down completely because in a large democracy its only when things reach breaking point that people are willing to change the system. You can't impose radical change from above. There was a lot of resistance to reforms from within the Congres party, he had to constantly explain to people what he was doing. The whole process was very difficult. Narasimha Rao had to steer the party through it.

Was Manmohan Singh attacked from within because he tried to bring change?

Daman: C Subramaniam was someone greatly admired by my father. I discovered while writing my book that Subramaniam pushed the green revolution, but at the political level he was called an agent of America. Radical change is hard to bring about. Subramaniam lost his seat. Pioneers don't get rewarded, pioneers are never remembered.

Was Manmohan Singh unsuited for politics?

Daman: I don't think he is a misfit in politics but manipulative politics does not come to him easily. He's not a wheeler dealer. But he survived, didn't he? Against all odds, against all the doomsayers he survived. He's not a reluctant politician. He enjoys a challenge, he takes risks and does not play safe. In fact, my father is a risk taker.

In 1991, the question was not about joining politics but on whether to become FM or not. Politics came along with the job, it's not as if he joined politics and then got the job. He took an enormous risk in 1991, he risked his entire life's reputation on economic reforms. 1991 was like a war situation.

Has Manmohan Singh’s reputation has been damaged by revelations in the books of Sanjaya Baru and Natwar Singh?

Daman: I haven't read either of the two books. They're not the sort of books I normally read. As far as I can tell Natwar's book is about politics which is not the kind of book am normally interested in reading. I am interested in politics as a process. I wrote this book because I wanted to discover my parents as individuals. And I think they enjoyed talking to me about their life, and reflecting on different parts of their life.

My mother is the power beside him rather than behind him. She's a people person and she has looked after him all her life. Work drives my father, he's a workaholic. Whether FM or RBI governor, he enjoyed all his posts. He had no regrets.

2005-2009 had not given Manmohan Singh’s family anything to laugh about?

Daman: Being PM was a massive responsibility, the amount of stress in a routine situation was enormous. He became PM under some unusual circumstances and he had to hit the ground running. It wasn't something he had been prepared for. The task was more difficult for him than it would be for anybody else ... the suddenness of it. Within days he had put together a team and get the policy framework moving. Then the coalition government had its own challenges. Being a civil servant gives you an insight on how policies are made, how they function, gives you access to information, knowledge, chance to observe how things work but when you are in charge that's an entirely different cup of tea, the responsibility, initiative, so much of it comes from you as one person, aside from of course the entire government machinery.

Did any member of his family ever want him to resign as PM when things got controversial, with all the scams and accusations?

Daman: We may have had our private thoughts but the lines between the political and the personal are very clear in the family. So we never really voiced anything. But we did worry a lot.

It's said the family wanted Manmohan Singh to resign when Rahul forced the cabinet to roll back the ordinance on criminal MPs?

Daman: My father was travelling when it happened, he was in the US. Of course, he was bothered. But that doesn't mean he had to show it. It's not as if he didn't see or hear what was being said about him. A lot of things bothered him. He is as sensitive as you or I. He just doesn't think it necessary to broadcast his feelings.

Did all the accusations and criticisms get to him and hurt the family?

Daman: Even as FM my father experienced an enormous amount of criticism - personal, professional and political. His family has been brought in, his daughters have been brought in that they work in American think tanks, etc. He's weathered it. He has the ability not let it affect him. But I feel very bad about it. I don't read newspapers or TV, I just switch off. But it would get to my son in school and it was very hurtful.

Didn't Manmohan Singh, the economist PM, in the end, fail to create the economy he would have wanted to?

Daman: Since 1981 my father was pushing growth oriented economics. He's never given up. People say he's worked in WB and IMF and my first reaction is get your facts right, he's ever worked in those places. That bothered me. The fact that people said he was toeing the IMF line never bothered me. But he always believed in growth as a way to alleviate poverty and he always knew what he was doing and I am glad he did it. In a specific context he did not go along with the radical shift of Jagdish Bhagwati and Padma Desai, but then the context changed. When he was FM there was need for a radical shift and he carried it out.

Manmohan Singh seemed to have a lot of respect for Indira Gandhi

Daman: Indira Gandhi inspired his respect, based on his personal interaction with her. She was a power house and she spoke to him as an equal. He was a little known civil servant, yet she heard his ideas, took his advice.

Manmohan Singh may have been hurt with Rajiv Gandhi's remark that the Planning Commission was a bunch of jokers

Daman: He wasn't there when it was said. There were a lot of reports in the media that it was directed at my father. Maybe it was a casual remark.

Did Manmohan Singh feel helpless about corruption in the system?

Daman: I spoke to my father a lot about corruption when I was writing this book. He said after he left Delhi School of Economics and entered the ministry of foreign trade, the then minister had a reputation for being corrupt. But my father said without evidence I cannot put a label on him. I thought that was significant. Later on, HM Patel, who my father admired a lot, was falsely accused, humiliated and he resigned from the civil service. My father had a great deal of regret that such a fine civil servant was subjected to this. My father often said the political system does create corruption, elections need money.

With Narasimha Rao

Narasimha Rao ‘told Manmohan he would be sacked if things didn’t work out well’

PTI | Aug 18, 2014 The Times of India

Woken up from his sleep to be informed of the "out of the blue" decision of his appointment as India's finance minister in 1991, Dr Manmohan Singh was jokingly told by Prime Minister Narasimha Rao that he would be sacked if "things didn't work out well".

Singh was asleep when PC Alexander, principal secretary to the Prime Minister, rang him up frantically to convey Rao's decision to appoint him as finance minister.

"The decision was out of the blue", Singh is quoted as having said by his daughter Daman Singh in her book "Strictly Personal: Manmohan and Gursharan", which covers the years prior to his becoming the Prime Minister in 2004. The book is based on Daman's conversations with her parents and hours spent in libraries and archives.

According to Singh, Rao's most important role was that he allowed the process of liberalization and opening up to go ahead, and gave it his full support.

Singh says Rao was first a little sceptic about the liberalization idea and had to be persuaded.

"I had to persuade him. I think he was a sceptic to begin with, but later on he was convinced that what we were doing was the right thing to do, that there was no other way out. But he wanted to sanctify the middle path — that we should undertake liberalization but also take care of the marginalized sections, the poor," recounts Singh.

"He also jokingly told me that if things worked well we would all claim credit, and if things didn't work out well I would be sacked," he said.

Referring to the imposition of Emergency in 1975, Daman says it came as a surprise to her father.

"Well, it was a surprise. There had been unrest, but nobody expected that Mrs Gandhi would go that far," she said.

When his daughter asked him how the Emergency affected the government servants, Singh replied, "I think there was a lot more emphasis on punctuality, on discipline. So some good things happened."

After the Morarji Desai-led Janata Party won a majority and came to power post-Emergency, a number of officers were shunted out but Singh kept his job.

Initially, Singh felt Desai was not quite fond of him. "When Morarji Desai became prime minister he had been told that I was close to the previous government. So he was quite rude to begin with. But after some time, he became very fond of me. Morarji Desai was fairly balanced, although people misunderstand him as a very rigid man. I think on the surface he was rigid, but he was amenable to persuasion," Singh is quoted as saying.