Om Puri

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

A profile

The Hindu, January 7, 2016

Namrata Joshi

Puri was born in Ambala, Haryana in 1950.

The performance that made viewers take note of Puri and implanted him in their consciousness was the one in which he barely spoke save that last, haunting scream of anguish..

Face of the marginalised

Those were the days of the zenith of Indian parallel cinema and Puri rode splendidly on the wave alongside virtuoso talents like Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil, among others, and supported by directors like Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani, Ketan Mehta, Kundan Shah and Sudhir Mishra.

“He was like water, taking the shape of every vessel he was put in. He soaked in the generosity and creative influences in his life,” remembers a friend. Some of Puri’s most significant performances in this time were all about the deprived and the disadvantaged.

Contributions to the cinema

The Times of India, Jan 7, 2017

The Hindu, January 7, 2016

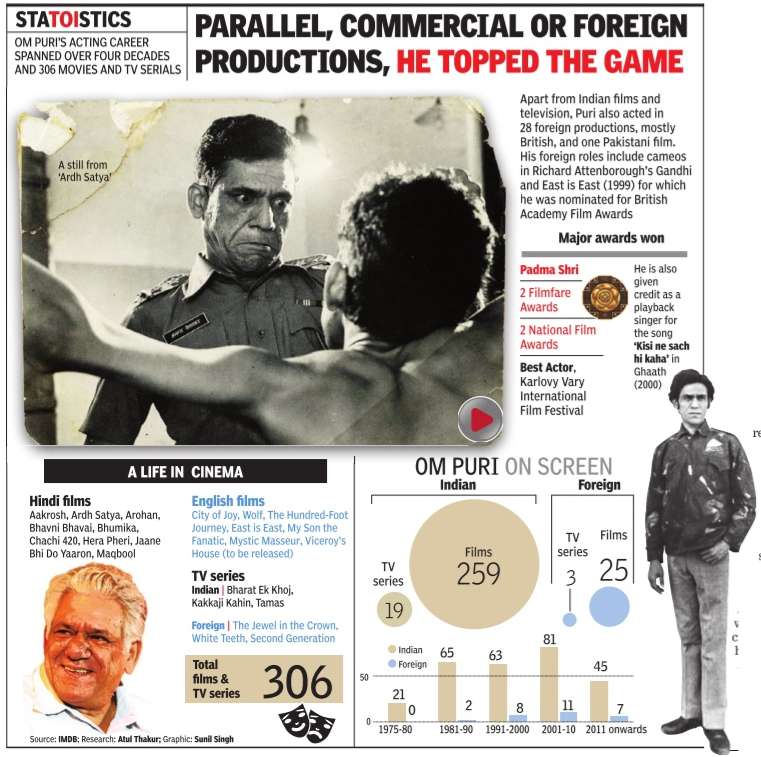

Staggering diversity in roles

With Naseeruddin Shah, Smita Patil and Shabana Azmi, Om Puri was part of the Fab Four considered the pin-ups of parallel cinema in the 1970s and '80s. His pockmarked face and lean frame challenged and redefined the idea of a male lead. His early award-winning performances in Shyam Benegal's Arohan and Govind Nihalani's Aakrosh were marked by a hitherto-unseen intensity that had the critics in swoon and the audience in awe.

Several stellar acts also came on the small screen, notably Satyajit Ray's TV film Sadgati, Nihalani's Tamas and Benegal's seminal Bharat Ek Khoj, where he notably played the 13th century Delhi Sultanat ruler Alauddin Khilji and 16th century Vijayanagar King Krishna Deva Raya II. Basu Chatterji's biting political satire Kakkaji Kahin underlined his flair for the funny , first unveiled in the classic feature, Jaane Bhi Do Yaaron.

Over the years, Om Puri not only made a seamless transition to mainstream Bollywood (Ghayal, Pyaar To Hona Hi Tha, China Gate, Mrityudand, Chachi 420) but also became one of the most recognizable Asian actors in British cinema (My Son the Fanatic, East is East) and Hollywood (City of Joy with Patrick Swayze, Wolf with Jack Nicholson, to name just two). That he had a 2014 box-office smash, The Hundred-Foot Journey , with Oscar-winner Helen Mirren, is a tribute to his durability and the space he had carved out for himself.

Swayze, co-actor for the much-talked but little-watched City of Joy , once said that Om Puri at least deserved an Oscar nomination for his performance as the rickshaw-puller Hazari Pal. “As an actor he has such diversity and depth. You look into his eyes and you read volumes,“ wrote the Hollywood star in the foreward of Unlikely Hero, a candid biography penned by Nandita, a former journalist.

Not all roles in Hollywood were as substantial; The Ghost and the Darkness and Charlie Wilson's War (where he played Pakistani President Zia-ul-Haq) being two apt examples. But his ouvre abroad only serves to underline the actor's long journey from an impoverished family in hinterland Punjab to one of India's most feted actors ever.

The biography reveals how at the age of seven, Om Puri washed cups and glasses at a tea shop while his father was in prison, how he gathered coal that fell from passing trains for fuel at home and how he took tuitions to support himself after being thrown out of home.

As a child, Om Puri wanted to be a soldier but was gradually drawn towards acting. Impressed by his performance in a Punjabi play , Anhonee, in college, the respected Harpal Tiwana invited him to join his influential theatre group, Punjab Kala Manch, where he took his first serious steps in learning the craft. He was paid Rs 150 per month; part of his job involved fetching eggs and babysitting.

It was a struggle, both social and financial: From overco ming his complexes for not being good at speaking the English language at National School of Drama to gathering funds to sustain himself at Film and Television Institute of India.

But after Nihalani's Aakrosh (1980) and Ardha Satya (1983), arguably the biggest success in the history of alternative cinema, hit the theatres, his hard times were over.

For Om Puri, the real challenge probably lay in finding avenues of creative satisfaction as New Cinema slowly ebbed away . This led him to act in dozens of indifferent movies, ma king many of his fans wonder why the actor of Mirch Masala, Dharavi, Gandhi, Bhavni Bhavai and Bajrangi Bhaijaan, was also working in Bin Bulaye Baraati. Perhaps the scars of the impoverished past remained with him. Perhaps he just loved work. To the actor's credit, he often managed to rise above the script's mediocrity .

Ironically, the performance that made viewers take note of Puri and implanted him in the viewers’ consciousness most strongly and everlastingly was the one in which he barely spoke save that last, haunting scream of anguish. His vacant eyes, gritty face and sheer intensity of presence told the tale of extreme oppression of the underprivileged, victimised tribal person Lahanya Bhiku, the role he became one with in Nihalani’s Aakrosh (1980).

Perhaps Puri’s own struggles in childhood and youth in Punjab brought them alive with a rare verity. Take for instance, the control and dignity with which he essayed the trauma of an untouchable shoemaker in Satyajit Ray’s TV film Sadgati (1981). Or the desperation of the poor land tiller in Shyam Bengal’s Arohan (1982).

When the parallel cinema movement ebbed, he was able to switch effortlessly to the mainstream as well. One the earliest memorable roles was that of the cop in Rajkumar Santoshi’s Ghayal (1990) and then again in Rajiv Rai’s Gupt (1997).

Just as much as the intensity he got identified with, Puri’s perfect comic timing made him win as many hearts. Most prominently as the corrupt, inebriated builder Ahuja in Kundan Shah’s Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro (1983), especially in the one long scene with the dead body of Commissioner D’Mello (Satish Shah). Assuming D’Mello’s coffin to be a broken down car he tows him away to his farm house, a moment that makes one double up in laughter till date. He was as incredibly funny as womaniser Banwari Lal in Kamal Haasan’s Chachi 420 (1997) too.

The strength of good actors lies not just in bringing author backed roles to life but in how they make their presence felt even in smaller roles and cameos. One of my favourite Puri performances is in Sai Paranjape’s Sparsh (1980). As the blind man Dubey, never once does he turn the disability into a caricature, as Bollywood is prone to, but lives his visual impairment, physically with all the inner turmoil and anxieties.

Then he towered in the climactic moments of Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala (1987), as Abu Mian the guard of the spice of the factory, who gives refuge to Sonbai and is the only man standing with the women against the arrogant subedar and the submissive village. He was the powerful Sanatan in Maachis (1996) the pivot on which rested Gulzar’s problematising of the insurgency in Punjab, on how innocent youth were forced to turn “terrorists” at the altar of the “system”.

Overseas triumphs

Puri was instrumental in being the ambassador of realistic Indian cinema abroad and ended up being part of a number of reputable and also some smaller foreign films, starting with a small role in Richard Attenborough’s epic Gandhi (1982). In Roland Joffe’s City of Joy (1992), he is the unlikely poor migrant pal of Patrick Swayze’s Max.

In Ismail Merchant’s In Custody (1993), he is the Hindi professor who loves Urdu poetry. He acted alongside Jack Nicholson in Mike Nichols’ Wolf (1994). Two smaller but significant turns were in Udayan Prasad’s My Son, The Fanatic (1994) where he is the liberal father of a hardliner son, and Damien O’Donnell’s East Is East (1999), where he is the conservative Pakistani father unable to deal with the generation gap and cultural rift with his half-British kids.

Last, but not the least, Puri was at the head of the quality content on television, in the glory days of Doordarshan, be it the sprawling Partition epic Tamas, Bharat Ek Khoj, Yatra, or the betel-chewing netaji in Kakkaji Kahin.

Somewhere in the midst of it all these media, the original platform — theatre — took a backseat. The last a friend remembers seeing him on stage was in a Punjabi adaptation of the play Tumhari Amrita, called Teri Amrita with Divya Dutta.

Friends remember him as a caring person and a dogged nurturer to his son Ishaan who has a visual impairment. Last few years, though, had not been great. The explicit revelations in the book, Unlikely Hero: The Story of Om Puri, by his second wife Nandita Puri broke him and the marriage as well. There was also a concomitant, unfortunate personal dissolution.

His only consequential presence of late was as the blacksmith sutradhar (narrator) in Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Mirzya last year. And the last straw, perhaps, was how he was humiliated publicly for his contrarian views on the Indian armed forces on television.

Om Puri dabbled in politics, occasionally putting his foot in the mouth. In 2011, he described MPs as “anpadh (illiterate)“ and “ganwar (rustic)“ during Anna Hazare's hunger strike at Delhi's Ramlila Maidan drawing howls of protest. He apologized later. The actor also engaged in a slanging match with a television news anchor over soldiers killed in terror attacks.