Delhi: Cuisine

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

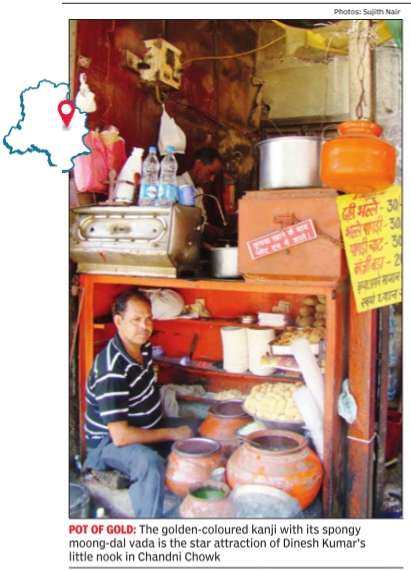

Kanji Vada

The Times of India, September 26, 2015

Dinesh Kumar, who sells kanji vada -from an alcove in a wall, which he shares with a chaiwala -said he would grant me a three-minute interview. He sits opposite a bridal-wear store, which till a few months ago housed the iconic sweetshop, Ghantewala, in Chandni Chowk.

“Kanji vada is a traditional recipe common to Vaishya, Khatri and Kayasthcuisines.It used to be prepared for Holi and during marriages,“ says food historian Pushpesh Pant. “Alas, it has become almost extinct.“

Dinesh says the entire family gets involved in the preparation at their rented house in Mori Gate. A few pots of kanji are made daily and left to ferment. Vadas, red meetha chutney and pudina chutney are prepared fresh. Sundays, when his shop is closed, are spent in making masalas that he sprinkles liberally over his dahibhalla and bhallapapdi.

Dinesh says the spongy moong dal vadas and kanji, which customers find so irresistible that they keep asking for refills, are the result of backbreaking effort -the reason why it's becoming a dying art. Apart from Dinesh, just a few push-cart hawkers sell it in Old Delhi.

Pant says the melt-in-the-mouth vada requires hard labour, involving arduous sessions of beating the batter with hands; the kanji has no other ingredients save mustard powder and salt.Apart from its great taste, kanji is also traditionally regarded as a good digestive.

Nihari

Sujith Nair, Served at dusk, this nihari’s worth the wait, March 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sujith Nair, Served at dusk, this nihari’s worth the wait, March 4, 2018: The Times of India

The Mughal-era meat preparation takes an entire day to cook, and many of its makers in Old Delhi come from a single extended family

It’s a meat stew that is cooked overnight and traditionally consumed at the crack of dawn with khameeri roti. But at least one Old Delhi shop has upended the nihari tradition.

“Come after dusk” is what you are told at Kallu’s if you happen to land up at the shop to relish this Mughalera breakfast.

It’s a shop with no signboard in one of the bylanes behind Delite Cinema in Daryaganj. Kallu’s nihari is hard to get unless you make it there within an hour after it’s ready to serve in the evening.

Mohammed Rehan, 28 and one of the youngest nihari makers in Old Delhi, relies on his grandfather’s recipe that was perfected by his father, Rafiquddin, alias Kallu.

Kallu, who passed away two years ago, started this shop in the late 1980s, around the same time when his cousin set up his eatery, Sheedu Nihari, near Turkman Gate. All of them, including Noora in Sadar Bazaar’s Bara Hindu Rao, are related and have learned nihari making at their family-run shop near Kalan Masjid in Turkman Gate area.

Rehan uses 50kg of buffalo meat for his nihari daily, barring Sundays, when the shop is shut. Work begins at 7am. Ghee is the first to hit the woodfired degh, followed by sliced onions and garlic. A few minutes later the meat chunks are dropped in.

Alongside, in another smaller vessel, around 20 maghaz (goat heads) are boiled in water over low charcoal fire.

Half an hour later, the contents of the degh get one good stir and in goes red chilli powder, masala (a blend of 20 spices sourced from Khari Baoli) and salt. This is followed by a shower of dried, caramelised onion powder.

An hour later, atta mixed in water is poured into the degh. As the stew slowly thickens, the stirring gets more vigorous. Workers light up extra wooden logs to keep the degh boiling for the next two hours.

Meanwhile, water is drained off the smaller vessel and each maghaz is checked. Those with cracks are wrapped with threads before being put into the degh along with raw nalli (bone marrow).

The degh is closed with an earthen lid and the mouth sealed with a long wet cloth. Two jute sacks are then wrapped around the degh from both sides and the nihari left to cook in low charcoal fire till the shop opens for the public at 5.30pm.

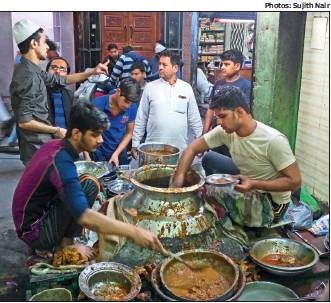

As expectant customers mill around, the seal is opened and the nalli and the maghaz are removed from the degh and kept aside for those who want to have their nihari with either or both.

By now a small crowd builds up in front of the shop, choking movement in the narrow lane. Rehan, along with his three brothers, fill up plates with nihari, top it with sliced green chillies and ginger and serve it with khameeri rotis.

Some prefer eating it inside the shop, sitting cross-legged on the floor, near the tandoor, while others lap it up standing in the lane.

If you still insist on nihari for breakfast, head to Shabrati Nihari in Jama Masjid’s Chitli Qabar area. But, mind you, they make only a small quantity overnight with around 12kg meat. So, the early bird grabs the nihari!

Shakarkandi

Azadpur’s bhatti

Sujith Nair, This is why your street shakarkandi tastes yum, March 25, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sujith Nair, This is why your street shakarkandi tastes yum, March 25, 2018: The Times of India

An Azadpur bhatti, which supplies chaat shops and vendors across Delhi, is keeping the art of sand baking alive

A chance conversation with a tikki seller in Old Delhi about where he gets his supply of baked aloo led us to this bhatti near Azadpur, Asia’s largest wholesale fruits and vegetables market.

Nestled within a residential block in Kewal Park Extension, it could easily be mistaken for a godown with sacks of shakarkandi (sweet potato) stacked outside. But take a peek inside and you see a huge furnace for heating up Badarpur sand mixed with sawdust. Scoops of this hot sand are transferred into a round aluminium vessel, and in goes a layer of bhutta (sweet corn) or shakarkandi; more sand is poured, an iron mesh placed as a separator, followed by another layer of food and sand, and then it’s left to bake.

A number of chaat vendors, bhutta sellers and caterers rely on bhattis around Azadpur Mandi to sand-bake their products. “Till the early ’90s, there were around 30 bhattis across Delhi, most of them in the Old Sabzi Mandi area. Only a few are left today,” says 52-year-old Dharmpal Prajapati, owner of the bhatti.

“Baking of bhutta, aloo and shakarkandi takes around 45 minutes while singhara (water chestnut) and kachalu are ready in 10-15 minutes,” says Dharmpal.

Bhutta sellers waste no time in packing the hot sweet corn into plastic covers and placing them inside sacks. “If bhutta is wrapped and packed well, it stays warm and fresh for around 12 hours,” says Subhash, a bhutta seller, as he ties a final knot to seal his sack.

Dharmpal says his father Madan Lal and uncle Munshi Lal ran a bhatti near Baraf Khana in the Old Subzi Mandi area. It shut down some years ago. Now, he and his cousin manage this bhatti. “Our clients usually buy their corn or tuber daily from the mandi and bring them here for baking. A few regulars purchase in bulk, leave it with us and get a small portion baked every day based on demand,” he says.

The bhatti also stocks and sells raw shakarkandi, the sweetest of which come from Karnataka’s Belgaum during the winter months. Though sweet corn is available mostly through the year, the desi bhutta season is between mid-June and August, he says.

“Unlike steam cooking where the corn or the tuber gains weight, in sand baking, we get lighter, more condensed food,” says Dharmpal. “We often get curious visitors asking us why the sand doesn’t stick to the tuber, how shakarkandi or aloo is baked without its skin getting burnt.”

Another bhatti in Badola Gaon near Adarsh Nagar Metro Station is equally busy. Dharampal, however, says: “I don’t wish to continue in this line after two years. It will be far easier for me to rent out this space.” The future of traditional sand baking seems bleak unless these bhattis adopt clean technology.

So next time, before you sink your teeth into a bhutta, pause and ask the seller — steamed or sand-baked?