Sons of the soil/ local job-seekers: 'reservations'/ quotas for: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Why such quotas fail

1995-2018

Why MP’s promise of 70% jobs to locals will fail, February 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: Why MP’s promise of 70% jobs to locals will fail, February 9, 2019: The Times of India

From: February 12, 2019: The Times of India

(With reports from Rajendra Sharma in Bhopal, Kapil Dave and Melvyn Thomas in Ahmedabad, Bhavika Jain in Mumbai, Sandeep Moudgal in Bengaluru, B Sivakumar in Chennai)

Kamal Nath’s plans ignore enforcement hassles faced elsewhere

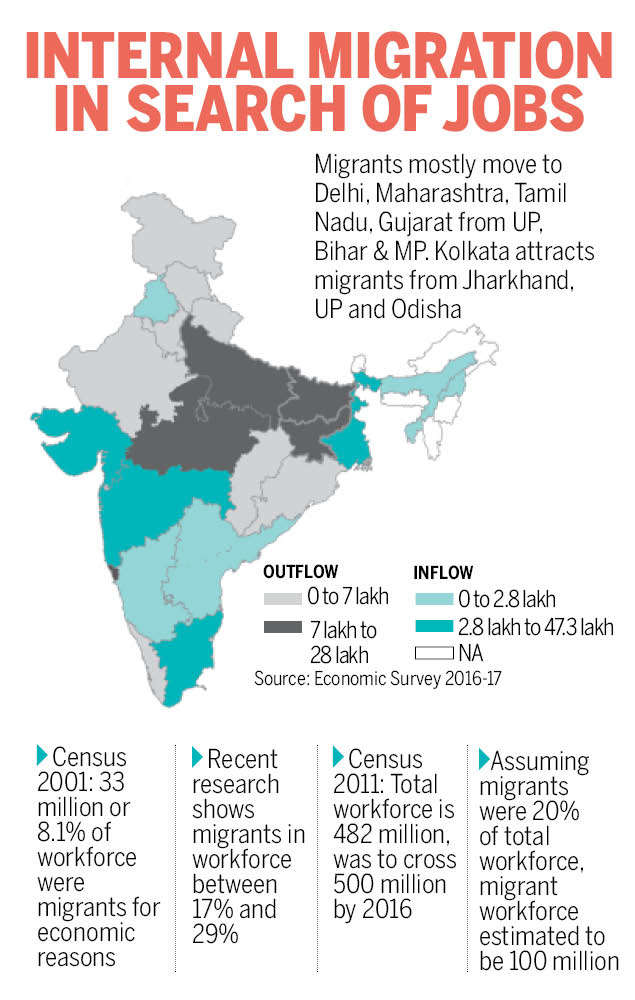

The Kamal Nath-led Congress government in Madhya Pradesh announced 70% reservation for locals in industries shortly after taking office. Across the country, such quotas have been introduced from time to time, but they have mostly remained on paper, mainly due to the reluctance of industries to carry out the policy and also because of an absence of enforcement mechanisms on the part of state governments.

In the past, industries have been hesitant — and understandably so — to dilute their hiring standards to meet a state’s job quota criteria. Chief minister Kamal Nath will have to do a delicate balancing act to ensure that investors still find it lucrative to do business in MP while meeting the quota criteria. During the previous BJP rule of 15 years, similar hurdles had compelled the full-majority government to bend norms to the demands of industries -- the 50% job promise remaining on paper. Still, investment didn’t flow.

“I personally welcome the provision for quota. We tried to implement 50% quota during our government but did not enforce it as a part of our industrial policy to bring investments. There were some hurdles related to skilled and technical manpower,” former state finance minister Jayant Malaiya told TOI.

Most industrialists suggest that those seeking jobs must have passed at least Class XII, but the quality of job-seekers is a problem. “We are aware of the standard of education in MP. There is an urgent need to improve it,” said higher education minister Jeetu Patwari.

Maharashtra in 2008 introduced 80% reservation for locals in industries that seek state incentives and tax subsidies. For industries that do not take incentives, this is still an indicative law.

Officials from the industries department of the state did not share data for the number of jobs created and those held by locals, but said the reservation policy didn’t take off.

According to them, there is no mechanism to check whether the stipulated quota of locals has been recruited. “We only check the number of employees from the Employees’ Provident Fund (EPF) accounts that a company opens. There is no way to find out how many of them are locals or from other states,” said a senior official.

He added that sometimes companies have been forced to hire ‘outsiders’ because of the lack of skill sets among local applicants for a particular job. “For sectors like chemical technology, textile and bio-technology, local employees are hard to find,” he explained.

The Gujarat story is no different. It introduced 85% reservation for locals as far back as 1995. The policy was never enforced, either in the private or public sectors. A significant number of workers in the ceramic, construction, textile, diamond and services sector come from Bihar, UP, West Bengal, Odisha and elsewhere.

Labour and employment minister Dilip Thakor said, “The idea of bringing a legislation for reserving jobs for locals was dropped as it was legally challenging and not implemented anywhere in India.”

In Karnataka, the government on December 2016 had planned to provide Kannadigas 100% reservation in mainly bluecollar jobs in private sector industries, except infotech and biotech. Early in 2018, the law department vetoed the idea on legal grounds, referring to articles 14 (right to equality) and article 16 (right to equal opportunity).

Later in January 2018, then advocate general (AG) Madhusudan R Naik said the government could suggest to the private sector to give “preference” to Kannadigas but could not force it to fall in line. The matter has not been raised since.

Meanwhile, MC Sampath, industries minister of Tamil Nadu, another highly industrialised state, had on January 5 promised that the government would ensure at least 50% reservation of jobs for residents of the state.

“We did not make it mandatory but … we have a clause which mentions that priority must be given to locals during recruitment. There is no fixed percentage for the companies to follow,” said a senior industry department official.

Industry bodies do not think much of these announcements. “These are political statements and are impractical in terms of implementation. Companies investing in a state recruit people based on skills to ensure good profits. Companies do not go by caste or creed, nor do they see which state one is from,” said Assocham secretary general D S Rawat.

Tamil Nadu’s strength has always been its talent pool. But that’s for white collared jobs. When it comes to labour participation in industrial activity, capital has always flowed to places where workforce is available in plenty. While there is no command or order to recruit locals, some industries, like textile in Tirupur or the Sivakasi fireworks hub, have always opted for locals. But that’s mostly due to availability of cheap labour.