Delhi: Groundwater

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Availability and quality of water

2000-2017: the level dips to the critical zone

From: AmitAnand Choudhary, 90% of city in critical zone as groundwater level dips, May 9, 2018: The Times of India

Could Lead To Severe Water Crisis, SC Told

The capital, already facing a severe drinking water shortage, is heading towards a more serious situation as the level of groundwater, continuously depleting in the last two decades, has resulted in 90% of the city being categorised as semi-critical or critical.

Presenting a dismal picture, the Central Ground Water Board told the Supreme Court that the water level has been decreasing from 0.5 metre to over 2 metres per year at different places in Delhi and could lead to a crisis if not halted. Compiling data on groundwater levels from year 2,000 onwards, the board in its report said water levels at all its 20 monitoring stations have seen a steady decline with areas around Chhatarpur, Dwarka and the President’s Estate hit the worst.

As per the report, 27% of the national capital territory’s 1,483 sq km had ground water at the level of 0-5 metres in 2010 but in 17 years this has shrunk to 11%. In 2000, ground water was available till 40 metres but at present water levels in 15% of Delhi, or around 222 sq km, have plunged to 40-80 metres.

The board has placed almost all of Delhi in semi-critical or critical zones except a few pockets of west and central Delhi, which have been declared safe as per 2005-10 data. The problem might be serious in NCR because of over-exploitation of ground water for construction.

Water table exploited up to 300% in parts of Ggn

Parts of Gurgaon suffer from severe over-exploitation of water to the extent of 300%. “Analysis of long-term water level data of May 2000 to the present period reveals that over the period, in areas categorised as over-exploited as per ground water resources estimation of 2013, mostly in South, South East, New Delhi, East, North East and also parts of West and South West district, water level decline rate varies from 0.5m per year to more than 2m per year at places,” the report said.

“There are some pockets, where change in water level is not significant or remain unchanged. Such pockets of shallow and rising water level areas are diminishing over the period. As such, major part of the state is under over-exploited and semi-critical category and in such areas, water levels are showing persistent declining trend during the last two decades,” it said.

Terming the report as “startling and very serious”, a bench of Justices Madan B Lokur and Deepak Gupta said immediate steps must be taken to avert the looming crisis. The court also pointed out that even the President’s Estate was under critical zone and asked the Centre “does it mean that you are not able to provide water to the President”?

Conceding that Delhi is staring at crisis, additional solicitor general A N S Nadkarni said the government will file a response on measures to be taken to deal with the problem. He said the entire world is facing the crisis and it is widely believed that next world war might be fought over water.

2004> 09> 17

From: Jasjeev Gandhiok, ‘New’ Delhi shows the rest how it should be done, March 23, 2019: The Times of India

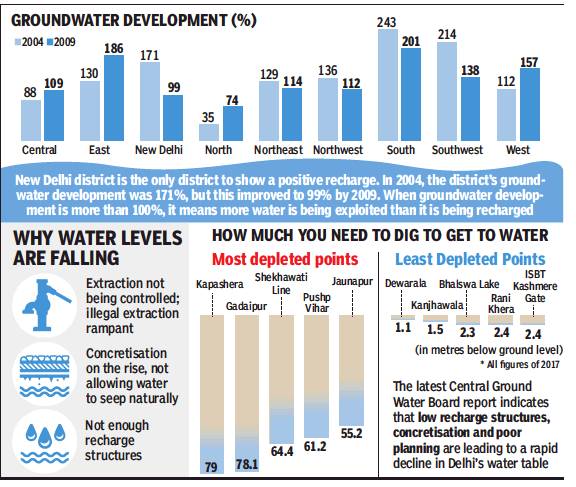

See graphic:

2004> 09> 17: Groundwater development in the various districts of Delhi.

As in 2017

Proposal To Ban Extraction From 1Km-Zone On Either Side Of Najafgarh Drain

The Central groundwater Board has categorised groundwater in Delhi into four zones according to availability and quality of water and issued guidelines for managing them. It has also recommended the cessation of all extraction of groundwater from a 1km-zone on either side of Najafgarh drain and from landfill and industrial sites because of the water there being highly polluted.

In its report called “Hydrogeological Framework and Groundwater Management Plan of NCT Delhi,“ released recently , CGWB has recommended extraction in Zone 1 areas, where groundwater is available at a depth of less than 8 metres below the ground. However, the report also said that many areas in this zone had poor quality water and this should be used for salt-tolerant crops or blended with clean water for non-drinking purposes.

The board said extrac tion projects should not be allowed in areas with declining water level (zone III).These included Delhi Cantonment, Vasant Vihar, Hauz Khas, Kalkaji, Chanakyapuri, Connaught Place, Punjabi Bagh, Paharganj, Preet Vihar and Vivek Vihar.CGWB has said if pumping continued at the current rate here, it would result in saline water. It has recommended rainwater harvesting and use of tertiary treated waste water for recharge of these areas.

The report warned that overexploitation was not only depleting water resour ces, but turning groundwater saline. Of the 13,491 million cubic metres (MCM) of groundwater in Delhi, 10284 MCM, or 76%, was brackish or saline. Among affected areas were Darya Ganj, Sa raswati Vihar, Punjabi Bagh, Najafgarh, Civil Lines, Defence Colony , and Delhi Cantonment. “Poor quality groundwater can be used for growing salt-tolerant crops like cotton, whe at, gaur, chickpea, soyabean, sugarcane and others,“ the report advised.

As for places abutting the Najafgarh drain, the report stated that the “presence of heavy metals has been re ported in groundwater along the drain. Therefore, groundwater in this zone is unsuitable for drinking and irrigation purposes...pesticides and bacteriological parameters have also been reported in isolated pockets.It is recommended that landfill sites should be selected after concluding hydrogeological surveys to minimise the risk of groundwater pollution“.

Shashank Shekhar, assistant professor of geology at Delhi University , who had conducted an independent study on the Najafgarh drain, pointed out, “Fluoride and even arsenic in groundwater in water samples of the Najafgarh drain can be attributed primarily to anthropogenic sources. Some heavy metals are, of course, found naturally in the environment, but they are not found in levels that are dangerous to human use.High nitrate contamination was also discovered in Timarpur, with fluoride levels above permissible limits in 20% of the samples.“

CGWB has identified a “potential aquifer zone“ along the western Yamuna canal which can yield around 5 million gallons per day (MGD) of water (the city's need is estimated to be 1,140 MGD by the 12th Five Year Approach Plan paper). The board also mapped tehsil-wise groundwater level trends between 2003 and 2013. Kalkaji tehsil showed the highest groundwater development at 277%, or much higher exploitation than the recharge capacity . It was followed by Vasant Vihar at 268%, Hauz Khas at 260% and Rajouri Garden at 232%.

2017/Mangar groundwater unfit: CPCB

Shilpy Arora, CPCB finds Mangar groundwater unfit, September 8, 2017: The Times of India

Villagers Helpless; Report Sent To NGT

The worst fears of green activists about contamination of groundwater due to flow of leachate from the defunct Bandhwari waste treatment plant have come true.Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has found that the groundwater in Bandhwari and Mangar villages are polluted to such a level that it is unfit for drinking. The board submitted its report to National Green Tribunal (NGT).

The green tribunal had asked CPCB in July to conduct laboratory tests of the groundwater in and around Bandhwari in the wake of a plea filed by environmentalist Vivek Kamboj in 2016. In its petition, Kamboj alleged that leachate from the solid waste management plant in Bandhwari, which has been lying defunct for the past four years, was flowing into underground aquifers, thereby contaminating the groundwater of the area.

“Nitrate in the groundwater samples from Mangar village and Bandhwari village are not complying with the drinking water standards, hence groundwater at Mangar and Badhwari villages is not fit for drinking purpose, but water can be used for bathing and irrigation purposes,“ states the report.

The board has blamed leachate formation at the defunct Bandhwari waste treatment plant for high levels of chloride, manganese, calcium and boron in the groundwater of these villages. “High values of manganese, calcium, boron and chloride content at a borewell at landfill site and a borewell at Dera village, (located) 500 metres away from landfill site are observed. Such contents... are higher than the acceptable upper limits for drinking purposes... This may be attributed to contamination of the borewells from landfill leachate,“ states the report.

While chlorides at a borewell has been found to be 888 mgl (milligrams per litre) -three times higher than the desirable limit -nitrate level at another borewell is 101.7 mgl (two times higher than desirable limit). The desirable limit of chlorides and nitrates should be below 250 mgl and 45 mgl, respectively . Similarly, highest levels of manganese, calcium and boron are 14.11 mgl, 285 mgl and 0.6 mgl, respectively . The desirable limit of manganese, calcium and boron, on the other hand, should be below 0.1 mgl, 75 mgl and 0.5 mgl, respectively .

The board also said in its report that there are chances that groundwater contamination could rise in the area. “Parameters like TSS (total suspended solids), TDS (total dissolved solids), BOD (biochemical oxygen demand), COD (chemical oxygen demand), arsenic and chloride are not complying with the discharge standards of the leachate and (it is) found that there is no proper management system for storage and treatment of leachate at the site,“ the report states.

2018: some groundwater has arsenic, fluorides; being overdrawn by 27%

Groundwater in parts of city has arsenic, fluorides: Report, June 9, 2018: The Times of India

From: Groundwater in parts of city has arsenic, fluorides: Report, June 9, 2018: The Times of India

From: Groundwater in parts of city has arsenic, fluorides: Report, June 9, 2018: The Times of India

Says Delhi Is Overdrawing Water By 27%

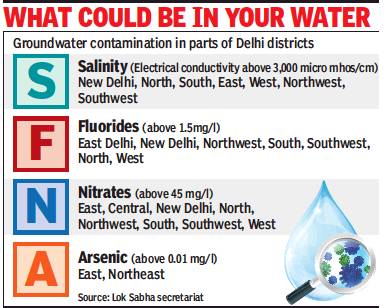

Even as the capital grapples with the problem of its fast depleting groundwater, there’s another cause for alarm regarding the city’s underground resource — contamination by lethal toxins such as arsenic, nitrates and fluorides in parts of Delhi.

A recent Lok Sabha secretariat report reveals that east and northeast districts of Delhi suffer from arsenic contamination of groundwater while other districts have recorded nitrate and fluoride pollution.

The report also quantifies how much the city is overdrawing its groundwater. The overexploitation was to the extent of 27% — that is, for every 100 litres that gets replenished, Delhiites draw out 127 litres. It’s based on analysis of groundwater use between 2011 and 2013, the latest year for which data is available.

The arsenic contamination is not widespread, but it may point to unacceptable ground pollution in the city.

“Arsenic contamination has been found in some parts of the Yamuna flood plains but it’s still a rare occurrence. Though arsenic pollution is considered geogenic (naturally occurring) in other parts of India, some papers have attributed arsenic contamination to fly ash from thermal power plants in Delhi,” said Shashank Shekhar, assistant professor of geology at Delhi University.

Shekhar said nitrate pollution in Delhi may be linked to sewage seepage, runoff from landfills into groundwater aquifers in different parts of the city.

Contaminated groundwater posing grave health risks

Fluoride contamination is restricted to the western part of Delhi where there is high groundwater salinity. Some studies have linked fluoride contamination to brick kiln activity while some say it is geogenic,” he said.

All three pollutants have severe health impacts. While arsenic is carcinogenic, high nitrate levels are known to cause methemoglobinemia, or “blue baby” disease. Shekhar said one of the reasons for high groundwater depletion is large scale concretisation.

“Most parts of the city have been concretised by way of urbanisation. There are very little recharge options. The focus should be on recharge, recycle and reuse in the city, otherwise it may be too late,” he said.

“The overexploite (groundwater) areas are mostly concentrated in three parts of the country — northwestern part of the country including Punjab, Haryana, Delhi and western Uttar Pradesh where although replenishable resources are abundant, there has been indiscriminate withdrawal of groundwater leading to over-exploitation,” says the report.

The other two over-exploited zones in the country are in the west (parts of Rajasthan and Gujarat) and peninsular India (parts of Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Tamil Nadu).

In its recent report called “Hydrogeological Framework and Groundwater Management Plan of NCT Delhi,” the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) had recommended zone wise groundwater extraction criteria.

Out of the four zones it had made, CGWB recommended stopping extraction of groundwater in a 1km-zone on either side of the Najafgarh drain and from landfill and industrial sites because of the water there being highly polluted.

Experts say while arsenic is carcinogenic, high nitrate levels are known to cause methemoglobinemia, or ‘blue baby’ disease

2018: Availability, district- wise

From: AmitAnand Choudhary, SC: Wake up or you’ll have zero groundwater by 2020, July 12, 2018: The Times of India

Court Takes Note Of Niti Aayog Report; Slams Centre, Delhi Govt

With Delhi staring at an alarming situation to reach virtually zero groundwater level by 2020, the Supreme Court on Wednesday slammed the Centre and Delhi government for not taking steps and asked them to file response on how to ward off the crisis.

A bench of Justices Madan B Lokur and Deepak Gupta took note of a Niti Aayog report projecting a disturbing picture that no groundwater would be available in Delhi and 21 other major cities by 2020 and asked the authorities concerned to pull up their socks to deal with the impending emergency.

As per the report, nearly half of India’s population could end up with no access to drinking water by 2030. But the water crisis could be worse for some of biggest metros - Delhi, Hyderabad, Bengaluru - which will run out of groundwater as early as 2020, according to the ‘Composite Water Management Index’ (CWMI) report by Niti Aayog.

Central Ground Water Board also projected a very dismal picture and told the apex court that groundwater in the capital has been continuously depleting in the last two decades and now 90 percent of the city has come under ‘critical’ condition.

In a comprehensive report filed in the court, the Board said the water level had been decreasing from 0.5 meter to more than 2 meters per year at different places in Delhi and could lead to a crisis if it is not stalled in the near future.

Compiling the data on groundwater level from 2000 onwards, the Board in its report said water level at all of its 20 monitoring stations witnessed steady decline and areas around Chhatarpur, Dwarka and President’s Estate were the worst hit. It placed almost entire Delhi on ‘semi-critical’ or ‘critical’ zones except a few pockets of West and Central Delhi which have been declared safe as per the 2005-10 data.

Referring to the reports, the bench said government authorities could not ignore the findings and had to act fast as only one and half years are left to avert the catastrophe. The court expressed anguish over the recommendations made by ministry of water resources as it did not mention any concrete suggestion to deal with the problem. It also noted that the Delhi government and Delhi Pollution Control Board did not even bother to file response on the problem as per its order.

It granted four weeks’ time to the Centre to file a comprehensive report spelling out immediate, intermediary and long-term measures to check the depletion of groundwater in the capital.

Rainwater harvesting

Status in 2018

From: Paras Singh, 2 years on, rain centres run dry as city fails to harvest gains, May 10, 2018: The Times of India

No Takers For Consultancy Helping Citizens Install Rainwater Harvesting Systems

To popularise the idea of rainwater harvesting, Delhi Jal Board, in association with an NGO, opened three “rain centres” two years ago. Today, after a promising beginning and at a time when groundwater resources are at a dire level, these centres are barely functional.

“The three centres provided free consultancy and helped people get rainwater harvesting (RWH) systems installed, but we did not build the harvesting units,” a DJB official said. “Now, hardly anyone visits us. We perhaps get one or two visitors in a month, sometimes not even that.”

Ironically, and perhaps indicative of the general disinterest in the capital’s falling water table, RK Puram, Dwarka and Lajpat Naga, where the three centres are located, have logged among the most worrisome drop in groundwater levels. When TOI visited the centre at RK Puram, where the last recorded water level was 44 metres below the ground, it found the unit locked. The lack of importance given to the project was evident in DJB officials being asked to shoulder the responsibilities of promoting RWH, in addition to their official work, once the partner NGO, Forum for Organised Resource Conservation and Enhancement (FORCE), withdrew.

Jyoti Sharma, founder of FORCE, explained that the water utility did not renew the partnership contract when it lapsed after a year. “These were advisory centres and we charged no money to provide our expertise,” Sharma said.

To increase water table recharge though RWH, the state government has made it mandatory for owners of properties built on an area of over 500 square metres to install water harvesting systems. Non-compliance attracts a penalty 1.5 times the water bill, while those who conform get a 10% rebate on the bill. An additional 5% rebate is offered for installing an effluent treatment plant. It is also mandatory for properties above 100sqm to install these units, though violation does not lead to penalties.

“The policy encourages people to fall in line, but lack of enforcement has failed to deliver. Also, waivers, amnesties and delays in deadline for compliance have hit the scheme,” Shar ma said. DJB officials agreed that the number of existing RWH systems is somewhere in the “few thousands” but nowhere “commensurate with the number of eligible households”.

DJB has relaxed troublesome conditions such as using activated charcoal as filtration medium. But experts say more tweaking is required for the idea to catch on. “Many properties in Delhi don’t have the required built-up free area and building a rainwater pit of the specified size could even damage the foundations. A policy should be made at community/ bulk user level,” said a FORCE member.

Sudha Sinha, general secretary of Federation of Cooperative Group Housing Societies, added the societies in Dwarka were bogged down by having to get annual fitness certificates for their RWH pits. “It takes over Rs 80,000 to get two RWH pits cleaned, so the costs for a cooperative society can go up to Rs 4 lakh,” Sinha pointed out.

2019: Only 1,200 harvesting units in city of 2 crore

From: Paras Singh, Losing ground: Just 1,200 rainwater harvesting units in a city of 2 crore, March 23, 2019: The Times of India

Delhi Ignoring Mandatory Requirement Despite Depleting Resources, Reveals RTI Reply

Delhi is fast staring at a groundwater crisis, but there is scant regard for bylaws that mandate rainwater harvesting for establishments built on plots of over 500 square metres. Just around 1,200 such units across the city have actually installed systems to route rainwater to underground resources, according to the reply filed by Delhi Jal Board in response to TOI’s RTI application.

Under the Delhi Water and Sewer (Tariff and Metering) Regulations, 2012, it is mandatory for all establishments over 500 sq m, whether new or old, to install rainwater harvesting systems. Pre-policy constructions on 100-500 sq m are exempted, but all new ones in this size category are required to install such systems. “For plots above 100 sq m, those built after 2012 come under the water harvesting by-laws,” an official reiterated. According to available records, DJB itself has 15,706 units measuring 100-500 sq m.

All properties adopting rainwater harvesting are provided a rebate of 10% in the water bill, but those mandatorily required to install harvesting systems and don’t are penalised with a bill that is 1.5 times higher than the actual amount. “As per the revenue management system, 1,254 consumers avail the rebate, while 11,388 have been charged the penal amount,” DJB said in its reply.

Niti Aayog recently warned that Delhi would deplete its groundwater by 2020 at the current rate of exploitation. The city receives an annual average of 617mm of rainfall.

Experts rue the poor enforcement of the policy, especially the long rope given to the new 100-500 sq m properties. “Repeated waivers, amnesties and shifting of compliance deadlines haven’t helped. Enforcement should be consistent for the impact to become visible,” noted Jyoti Sharma of NGO Forum for Organised Resource Conservation and Enhancement.

Environmentalist Vinod Jain suggested following the Tamil Nadu model of rain harvesting. “There, the government builds the required system and charges the people for its use,” he said. “If they refuse to pay up, water and sewage connection are severed.”

There is also a need to tweak the policy to conform to ground realities. “Many properties don’t have the built-up free area required for installing a rainwater pit,” pointed out Sharma. “Pooling of resources should be permitted and communities allowed to carry out water harvesting collectively.”

Dinesh Mohaniya, DJB vice-chairman, revealed that DJB was also adopting a zero liquid discharge policy to arrest groundwater depletion. “Under this policy, waste water generated by the big consumers will be cleaned, refined and reused for horticulture, thus avoiding use of fresh water,” he said. He also noted that Delhi officially got rain for only 22 days in a year, rendering the harvesting system not too useful. “In contrast, the zero liquid discharge systems will feed the aquifers all 365 days,” he concluded.

2004>09>17: Greater success in NDMC’s New Delhi district

Despite the Niti Aayog cautioning that Delhi could run out of groundwater by 2020, and with summer approaching rapidly, the districts of Delhi, save for New Delhi, appear ill-equipped to harvest rainwater. A recent study by Delhi University linked an improvement in the water table

in the New Delhi district to the increase in rainwater harvesting systems installed there, a clear sign that the capital could do with reduced exploitation and increased natural recharge during the rainy season.

New Delhi is the only district to show ‘positive’ groundwater development, falling from 171% in 2004 to 99% in 2009. “When the figure is more than 100%, it means more water is being extracted than being replenished. Falling below 100% is a good sign,” explained Shashank Shekhar of the department of geology at DU and researcher on the study.

Shekhar said the New Delhi district had a large number of government buildings, most of them over 500 square metre in size and so mandatorily required to have rain harvesting systems. Other buildings too have pitched in and more water is being recharged despite the region being fairly concretised. “If you look at 2014 data and compare it with 2004, groundwater levels are starting to rise in New Delhi areas, and this is an example of how rainwater harvesting can help replenish groundwater,” said Shekhar.

For other districts to similarly succeed, the contribution of Delhi Jal Board is considered crucial. Suresh Rohilla, water programme director, Centre for Science and Environment, said DJB has to ensure that the mandated buildings have rain harvesting infrastructure. “We are seeing action, but only due to the pressure of the National Green Tribunal,” said Rohilla. “Otherwise, people are unaware of how to install rainwater harvesting system and that is where the problem lies. DJB has to provide the knowledge and expertise to those willing to pay to have these installed on their properties.”

The latest Central Ground Water Board report has indicated that low recharge structures, increasing concretisation and poor planning are leading to a rapid decline in Delhi’s water table. In almost 15% of the capital, groundwater lies at a depth of 40 metres or more, and almost all of south Delhi, central Delhi and east Delhi use more groundwater than is being replenished.

Vikrant Tongad, a groundwater activist who has filed several petitions in NGT, suggested that long-term planning had to consider not only harvesting infrastructure, but also re-use of water. “Singapore, which has become self-sufficient in water, recycles all sewage water,” he said. “We need to stop relying on groundwater and focus on how to re-use available sewage water.”