Delhi: Cuisine

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Chaat

Kulle chaat

Sujith Nair, Kulle chaat is a cool treat on hot summer days, April 15, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sujith Nair, Kulle chaat is a cool treat on hot summer days, April 15, 2018: The Times of India

This Purani Dilli street dish comes in a ‘cup’ made of potato, tomato, or whatever fruit you like

During Delhi’s scorching summers, kulle chaat is a refreshing treat. The spicy mix traditionally comes in a scooped-out potato ‘cup’ (kulle) but vendors are now experimenting with fruits, tomato and cucumber as the base. Made popular by food walks, this new avatar of kulle chaat is lapped up by tourists and shoppers in Chawri Bazaar and Sitaram Bazaar, but Purani Dilli frowns on these upstarts who have tinkered with the original.

“How can you make kulle with tomato?” agonises Ashok Mathur, 48, a fifth-generation Old Delhi resident, who has grown up eating Sultan’s Kulle in his neighbourhood. “Kulle used to be only made of aloo or shakarkandi (sweet potato). The spicier, the better! This was followed by a cup of tea,” Mathur recounts, sitting in his 100-year-old home in Roshanpura.

Arun Kashyap, 32, sits at the same spot where his great grandfather, Sultan Singh, parked himself on a raised platform outside a Jain household, in a narrow bylane that runs parallel to Nai Sadak.

Kashyap says he has grown up hearing tales of the legendary Mukesh — the singer’s family lived in Old Delhi’s Chelpuri — eating kulle made by his great grandfather when he was a roaming hawker with a khomcha (stand).

“Banana was the first fruit our family experimented with for customers who liked fruit chaat but didn’t want the traditional aloo as the base for kulle. Now, we make it with more fruits but the regulars insist on aloo,” says Kashyap, who also serves aloo chaat and tikki.

The aloo is sand-baked at a bhatti in the Old Subzi Mandi area in the morning. By afternoon it reaches Roshanpura, where Kashyap scoops out the middle to make space for the filling. He starts with a few pinches of a homemade masala which, Kashyap says, has 36 ingredients.

This is followed by boiled chana (small chickpeas), kala namak, roasted jeera powder, black pepper, boora (powdered sugar), pomegranate seeds, a squeeze of lemon and finally topped with sliced ginger. This was a vantage point when Sultan set up base here 80 years ago; but changing demography and competition from chaat vendors on the main roads, have made life tough for his great grandson.

But support from the local community has kept Sultan’s kulle going. “We use the space outside a Jain family’s house but they don’t charge us. They let us store our wares inside, and even pay for the kulle they consume,” says Kashyap. His chaat still draws members of the Mathur families, who once occupied most houses in this neighbourhood. Today, the homes have given way to shops and godowns. “Sultan’s masala runs in our blood,” says Ashok Mathur, talking nostalgically about how people used to choke the lane during Ram Navami to relish the kulle served on dhak patta.

So, next time you take Nai Sadak to cross over from the food streets of Chandni Chowk to Jama Masjid, do try out this palate cleanser.

Jain, saatvik food

Jai Tara in Dharampura

Sujith Nair, Old Delhi’s saatvik pit stop, May 13, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sujith Nair, Old Delhi’s saatvik pit stop, May 13, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sujith Nair, Old Delhi’s saatvik pit stop, May 13, 2018: The Times of India

A Dharampura shop’s kachoris and samosas have plenty of takers among the Jain community

It takes a heritage walk through a narrow lane amid imposing havelis — straight out of an old photograph in a fading album showing glimpses of a glorious past — to reach this sweet and namkeen shop in Old Delhi’s Dharampura.

This saatvik haven is one of its kind — pamphlets on the counter, and photographs and posters on walls listing the Jain principles that Jai Tara and its owner stand for.

What draws the morning crowd is their khasta kachori and methi (fenugreek) chutney with an optional topping of chhole. The crisp kachoris are stuffed with ground urad dal and masala. “We don’t use onion, potato, garlic, carrot or any root vegetable in our preparations,” says Satish Jain Bharti, 58, whose family started Jai Tara in the mid-1940s. “Jain families, who generally prefer not to eat out, do come here.”

“We only use filtered water, and our sweets are not topped with silver vark either,” says Bharti, who also runs an NGO. “A visit to a resettlement colony, as a college student, changed my life,” says Bharti, who gave up woollens in the mid-70s and has stuck to his trademark white cotton shirt and dhoti ever since.

Around the same time, Jai Tara too underwent a transformation — from a milk shop famous for its Sonipat ka peda, barfi and hot kulhar doodh, to a sweet and namkeen shop — with the arrival of Vijay Bahadur, a young halwai from Agra.

Bharti’s father engaged Bahadur to make kachoris in the morning, and later introduced matar samosas in the evening. “We used to make carrot halwa, too, but Satishji’s mother felt we should not serve things they themselves didn’t consume,” says Bahadur, now all of 62.

“We use pista and badam as topping for moong dal barfi instead of the traditional silver leaf. Balushahi is prepared during summers, ghewar in rainy season, dry gujiyas during Holi and Diwali festivities and gulab jamun through the year,” says Bahadur.

This quaint shop sells only limited quantities. Regular customers know what is prepared at which time of the day and come accordingly to pick up their favourite sweets and snacks. Balushahi, prepared in the evening, usually runs out before the shop shuts for the day.

Bahadur says that while some old families have moved out of Dharampura, they regularly visit the Jain temples in the neighbourhood. Invariably, they drop in at their shop.

So, if fresh saatvik food is on your mind, it is time to say Jai Tara!

Kanji Vada

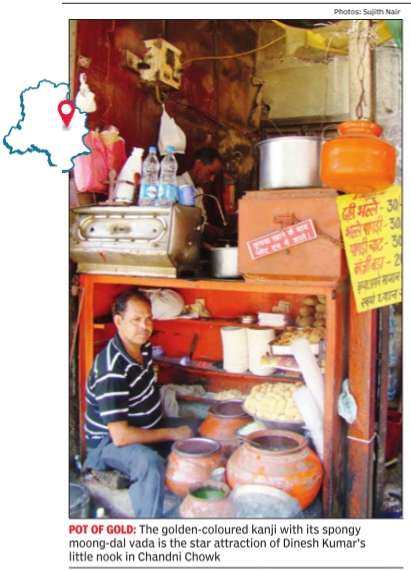

The Times of India, September 26, 2015

Dinesh Kumar, who sells kanji vada -from an alcove in a wall, which he shares with a chaiwala -said he would grant me a three-minute interview. He sits opposite a bridal-wear store, which till a few months ago housed the iconic sweetshop, Ghantewala, in Chandni Chowk.

“Kanji vada is a traditional recipe common to Vaishya, Khatri and Kayasthcuisines.It used to be prepared for Holi and during marriages,“ says food historian Pushpesh Pant. “Alas, it has become almost extinct.“

Dinesh says the entire family gets involved in the preparation at their rented house in Mori Gate. A few pots of kanji are made daily and left to ferment. Vadas, red meetha chutney and pudina chutney are prepared fresh. Sundays, when his shop is closed, are spent in making masalas that he sprinkles liberally over his dahibhalla and bhallapapdi.

Dinesh says the spongy moong dal vadas and kanji, which customers find so irresistible that they keep asking for refills, are the result of backbreaking effort -the reason why it's becoming a dying art. Apart from Dinesh, just a few push-cart hawkers sell it in Old Delhi.

Pant says the melt-in-the-mouth vada requires hard labour, involving arduous sessions of beating the batter with hands; the kanji has no other ingredients save mustard powder and salt.Apart from its great taste, kanji is also traditionally regarded as a good digestive.

Nihari

Sujith Nair, Served at dusk, this nihari’s worth the wait, March 4, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sujith Nair, Served at dusk, this nihari’s worth the wait, March 4, 2018: The Times of India

The Mughal-era meat preparation takes an entire day to cook, and many of its makers in Old Delhi come from a single extended family

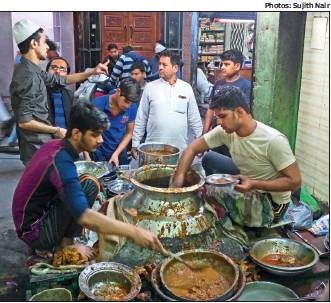

It’s a meat stew that is cooked overnight and traditionally consumed at the crack of dawn with khameeri roti. But at least one Old Delhi shop has upended the nihari tradition.

“Come after dusk” is what you are told at Kallu’s if you happen to land up at the shop to relish this Mughalera breakfast.

It’s a shop with no signboard in one of the bylanes behind Delite Cinema in Daryaganj. Kallu’s nihari is hard to get unless you make it there within an hour after it’s ready to serve in the evening.

Mohammed Rehan, 28 and one of the youngest nihari makers in Old Delhi, relies on his grandfather’s recipe that was perfected by his father, Rafiquddin, alias Kallu.

Kallu, who passed away two years ago, started this shop in the late 1980s, around the same time when his cousin set up his eatery, Sheedu Nihari, near Turkman Gate. All of them, including Noora in Sadar Bazaar’s Bara Hindu Rao, are related and have learned nihari making at their family-run shop near Kalan Masjid in Turkman Gate area.

Rehan uses 50kg of buffalo meat for his nihari daily, barring Sundays, when the shop is shut. Work begins at 7am. Ghee is the first to hit the woodfired degh, followed by sliced onions and garlic. A few minutes later the meat chunks are dropped in.

Alongside, in another smaller vessel, around 20 maghaz (goat heads) are boiled in water over low charcoal fire.

Half an hour later, the contents of the degh get one good stir and in goes red chilli powder, masala (a blend of 20 spices sourced from Khari Baoli) and salt. This is followed by a shower of dried, caramelised onion powder.

An hour later, atta mixed in water is poured into the degh. As the stew slowly thickens, the stirring gets more vigorous. Workers light up extra wooden logs to keep the degh boiling for the next two hours.

Meanwhile, water is drained off the smaller vessel and each maghaz is checked. Those with cracks are wrapped with threads before being put into the degh along with raw nalli (bone marrow).

The degh is closed with an earthen lid and the mouth sealed with a long wet cloth. Two jute sacks are then wrapped around the degh from both sides and the nihari left to cook in low charcoal fire till the shop opens for the public at 5.30pm.

As expectant customers mill around, the seal is opened and the nalli and the maghaz are removed from the degh and kept aside for those who want to have their nihari with either or both.

By now a small crowd builds up in front of the shop, choking movement in the narrow lane. Rehan, along with his three brothers, fill up plates with nihari, top it with sliced green chillies and ginger and serve it with khameeri rotis.

Some prefer eating it inside the shop, sitting cross-legged on the floor, near the tandoor, while others lap it up standing in the lane.

If you still insist on nihari for breakfast, head to Shabrati Nihari in Jama Masjid’s Chitli Qabar area. But, mind you, they make only a small quantity overnight with around 12kg meat. So, the early bird grabs the nihari!

Shakarkandi

Azadpur’s bhatti

Sujith Nair, This is why your street shakarkandi tastes yum, March 25, 2018: The Times of India

From: Sujith Nair, This is why your street shakarkandi tastes yum, March 25, 2018: The Times of India

An Azadpur bhatti, which supplies chaat shops and vendors across Delhi, is keeping the art of sand baking alive

A chance conversation with a tikki seller in Old Delhi about where he gets his supply of baked aloo led us to this bhatti near Azadpur, Asia’s largest wholesale fruits and vegetables market.

Nestled within a residential block in Kewal Park Extension, it could easily be mistaken for a godown with sacks of shakarkandi (sweet potato) stacked outside. But take a peek inside and you see a huge furnace for heating up Badarpur sand mixed with sawdust. Scoops of this hot sand are transferred into a round aluminium vessel, and in goes a layer of bhutta (sweet corn) or shakarkandi; more sand is poured, an iron mesh placed as a separator, followed by another layer of food and sand, and then it’s left to bake.

A number of chaat vendors, bhutta sellers and caterers rely on bhattis around Azadpur Mandi to sand-bake their products. “Till the early ’90s, there were around 30 bhattis across Delhi, most of them in the Old Sabzi Mandi area. Only a few are left today,” says 52-year-old Dharmpal Prajapati, owner of the bhatti.

“Baking of bhutta, aloo and shakarkandi takes around 45 minutes while singhara (water chestnut) and kachalu are ready in 10-15 minutes,” says Dharmpal.

Bhutta sellers waste no time in packing the hot sweet corn into plastic covers and placing them inside sacks. “If bhutta is wrapped and packed well, it stays warm and fresh for around 12 hours,” says Subhash, a bhutta seller, as he ties a final knot to seal his sack.

Dharmpal says his father Madan Lal and uncle Munshi Lal ran a bhatti near Baraf Khana in the Old Subzi Mandi area. It shut down some years ago. Now, he and his cousin manage this bhatti. “Our clients usually buy their corn or tuber daily from the mandi and bring them here for baking. A few regulars purchase in bulk, leave it with us and get a small portion baked every day based on demand,” he says.

The bhatti also stocks and sells raw shakarkandi, the sweetest of which come from Karnataka’s Belgaum during the winter months. Though sweet corn is available mostly through the year, the desi bhutta season is between mid-June and August, he says.

“Unlike steam cooking where the corn or the tuber gains weight, in sand baking, we get lighter, more condensed food,” says Dharmpal. “We often get curious visitors asking us why the sand doesn’t stick to the tuber, how shakarkandi or aloo is baked without its skin getting burnt.”

Another bhatti in Badola Gaon near Adarsh Nagar Metro Station is equally busy. Dharampal, however, says: “I don’t wish to continue in this line after two years. It will be far easier for me to rent out this space.” The future of traditional sand baking seems bleak unless these bhattis adopt clean technology.

So next time, before you sink your teeth into a bhutta, pause and ask the seller — steamed or sand-baked?

Sheermâl

2019: new varieties

From: Mohammad Ibrar, ‘Jung-e-Sheermal’ plays out in the shadow of Jama Masjid, April 4, 2019: The Times of India

In the lanes of Matia Mahal in the shadow of the Jama Masjid, everyone knows what sheermal is. That pinkish brown flatbread of Arabic provenance recalls feasts of indulgence. Whose salivary gland remains idle at the thought of rich qormas carried on the slightly sweet, chewy sheermal with its faint aroma of sweetened milk and saffron? Yes, that’s what a sheermal is.

But is it? Go to Matia Mahal these days, and men hail you from the eateries, offering tasting plates of their versions of the revered flatbread. And not all of them taste like the traditional sheermal.

The ‘Jung-e-Sheermal’ is well and truly under way in the vicinity of the neighbourhood’s Pakwaan Sweets, the establishment that brought the flatbread out of the exclusive ambience of wedding feasts and elite indulgence and into the streets three decades ago. In recent weeks, many new enterprises from Meerut have been serving innovative varieties of sheermal and the locals have had to respond with their own creations.

Sheermal warriors use flavour as weapon

So you can today have sheermals that are khoya-filled, nut encrusted, coated with grains of sugar, even mango flavoured.

Fazlur Rahman Qureshi, owner of Pakwaan Sweets, sniffs with condescension and pronounces, “What these shops from Meerut sell is not sheermal, but bakery products.” Yet the locality does not seem to put much stock in culinary traditions. As Abu Sufyan, a resident of Turkman Gate, discloses, he does buy the original version “for its authentic Delhi taste” but is happy at the new offerings because “they bring variety to the food scene in the city and give more options to the people”.

The options are anything but traditional. “We have the most flavourful sheermals that the locals are beginning to be infatuated with,” boasts Siraj, who manages the Haji Nadeem Sheermal Centre. He sells three varieties of the bread, and depending on the price, they are either encrusted with pistachio, cashew nut and almond and dipped in ghee or have just a coating of refined oil or dalda. Having served their brand of sheermal stuffed with sweet khoya in Meerut for over two decades, they came to medieval India’s capital in search of a new clientèle. “Price is not a factor for the people here and they have become fans of our fare,” Siraj says.

Haji Imran, of the eponymous Haji Imran Sheermal Shop, a stone’s throw from Siraj’s establishment, is indignant. “They only copy us but can’t make as delectable a sheermal as we do,” he says. Imran’s offerings are similar to Haji Nadeem’s with only a slight variation in the flavour, but he continues, “It was I who first decided to come to the capital from Meerut. I opened a shop in Jaffrabad in north-east Delhi seven months ago and then aware that it is old Delhi that attracts food lovers, I decided to move here. Now, we have a huge following.”

The traditionalist in Qureshi almost splutters at the claims of the new comers. We sell the “original and true variety of the saffron coloured flatbread with a hint of cardamom”, he almost screams. He might turn his nose up at the nouveau sheermalists, but he has ironically had to acknowledge the threat to this business by coming up with his own twists. Pakwaan Sweets now has on its menu masala sheermal, which is redolent of garam masala, the light and fluffy Irani sheermal, also called Toosa, and a sugary iteration designated, almost derogatively, the chini roti.

But of all Qureshi’s creative forays, the best was to wed the sheermal with the mango. “To make this type, we soak the flour in milk and mango juice,” reveals the old sheermal maker of his recent addition. “We then cook the sheermal with juliennes of mango as garnish. The taste is so good that we never seem to have enough to sell.”

The war for sheermal supremacy begins early in the morning with the kneading of the milk-soaked dough. “We continue to knead through the day and well into the night for as long as people come looking for sheermal,” says Haji Imran. By noon, the khoya-filled sheermal is ready to be put in the tandoor after being crushed under a coating of dry fruit. The grilled flatbread is then soaked in ghee or in oil, depending on how expensive the eater’s taste is. “The bread can stay fresh for 12 days,” one of the cooks claims.

After this brief digression, the battle continues. “Ours is the best because we put a lot of pure milk, ghee and other fresh items,” insists Qureshi. “They are light and best eaten with kheer or qorma, unlike the stuff offered by the new ‘mela shops’.” His rivals don’t hear the derisory tone in his voice. Even if they did, they wouldn’t perhaps have time to retort, intent as they are on satiating the cravings of the crowd in their shops.