Brahm Khatri: Hyderabad

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

The Brahm(a) Kshatriyas

Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

From: Hema Malini Waghray, September 7, 2020: The India Forum

The Brahma Kshatriyas were culturally and socially like the Muslim community around them. Their language, dress, jewellery, food habits, and other material forms of life matched the dominant culture. The Khatri way of life has been a process of cultural syncretism: incorporating another culture as one’s own and an amalgamation of disparate schools of thoughts and cultures.

The first known account of a community member is of Chabileram of the Shah family. He came to Hyderabad along with Asaf Jah I, the Mughal governor of the Deccan, who founded the independent princely state and ruled from 1724 to 1748. Raja Bansi Lal, a descendent of Chabileram, too was employed in the office of a later Nizam. Another early record is of Mahipat Ram of the Sehgal family, who was in the bureaucracy of the second Nizam and became the governor of Berar. Some accounts term Mahipat Ram as the first freedom fighter of Hyderabad for his anti-British stance, and he has a street in Hyderabad named after him.

By 1882, the Brahma Kshatriyas had become a small identifiable group of people of about 70 members. Govind Lal, a community member and researcher, says that the members came together around that time and set up formal associations. The year 1882 is significant because it was the year that the community set up the Mufeed-ul-Annam school in Hyderabad. They would later set up the Quomi Fund, a cooperative society to aid the education of community members.

The community’s foundations and outlook lie in the socio-political nature of Muslim rule and later, the freedom struggle and nation-building. This photo essay illustrates how the community became a part of the larger society of Hyderabad through its social institutions and its syncretic culture that enabled a way of life. I present various artifacts—diaries, photographs, documents, and other objects—which are visual representations of this syncreticism. (This information is drawn from family documents and community member interviews, and are part of a larger archival research project.)

The photograph above, at the beginning of this article, is of an anjuman, or gathering, of a group of Brahma Kshyatriyas, some time in 1937-38. It could have been a meeting of the Quomi (community) Fund, with members gathered for election of the cooperative society. The Quomi Fund was the popular name of the Brahma Kshatriya Kharzai Talimi (Brahma Kshatriya Educational Loan Society) that was set up in 1926. There are 65 members in the photograph, of whom 63 have been identified by Govind Lal.

The other possibility is that, since there are children present, the anjuman might have been the holiday gathering for Dussehra. The Dussehra festival, unlike Diwali, is an important festival for the Brahma Kshatriyas and is celebrated with new clothes and biryani. There is also the practice of mulaqaat — meeting-and-greeting close and extended family members — similar to the Eid mulaqaat among Muslims.

The men are dressed in sherwanis and sport the six-inch high Rumi topis. According to the social norms of the times, this headgear was required for all social events. This attire was the style of the Nizams and of the Muslim populace of Hyderabad. To this day, sherwanis, topis, and dastaars (a headgear used at weddings) are a part of festive and wedding wear amongst the Brahma Kshatriyas.

The Mufeed-ul-Annam school, set up by the community in 1882 and still in existence in the Old City part of present-day Hyderabad, is depicted here on an early 20th century planning map for Hyderabad. The Brahma Kshatriyas sought modern education for employment in the bureaucracy, which prompted the founding of the school. It offered Urdu and later English medium education to the children of the community members and also to the general public.

This institution created the circumstance for progress by providing access to education in a time when there were not many schools in Hyderabad. Since its founding, almost all the members of the community until the middle of the 20th century, including my parents, were educated in this school.

The map was created by the English engineer Leonard Munn as part of the Hyderabad Municipal Survey of 1912-1915 to plan the city after the Great Flood 1910.

Members of the community invested in the Quomi Fund, which gave loans to members for their children’s higher education or for weddings. It raised funds either from donations from rich jagirdars or from subscriptions.

The share certificate in the photograph is dated 1 Shahrewar 1342 of the Fasli era, the official calendar of the Nizam state, corresponding to 7 July 1933. On the masthead of the certificate is Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth who is worshipped by the Brahma Kshatriyas during Dhanteras and Diwali. The text reads:

This is to certify that Jaggu Bhai Saheb has purchased one share of Rs. 10 of the Osmania currency from our society. The total amount has been paid according to the rules of the society.

Hence the shareholder should abide by the rules and regulations of the society with immediate effect.

The Quomi Fund was an institution that bound the Brahma Kshatriyas together in pursuit of their financial goals and stability in a period in which banks were not very common. Well into the 1980s, individual goals for education came to fruition when this cooperative society that gave loans to fulfil them. I have memories of my parents discussing the trip to the Quomi Fund office and my family benefiting from its loans. My sister’s admission to a private college and to a course at the Institute for Public Enterprise in Hyderabad was the result of a loan from the Quomi Fund.

The panchang is from the diary of Dilsukh Ram (1901- 1988), who was trained in accountancy and was a member of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England and Wales. He was one of the earliest chartered accountants in India and the only one in Hyderabad when he began his practice. He was a member of the committee that started an organisation called Hyderabad Development Society and as a secretary was instrumental in the construction of housing colonies in Dilsukhnagar, now named after him.

Dilsukh Ram’s diary also contains his translations of the Bhagavad Gita into Urdu. The excerpt in this picture is from the second chapter of the Gita, where Krishna implores Arjuna to fight without fear and explains the importance of detachment.

Both here and in the case of the panchang, the use of a language now associated as “Muslim”, for documents with Hindu religious connotations speaks to the blurring of religious boundaries and signifies the cultural syncretism of the community.

The large brass plate, called a paraath ( view of the rim above), was used in large families or in community gatherings such as weddings. Paraths were either rented from zamindars or borrowed from relatives during such occasions. They were used to mix large quantities of flour or to store vegetables.

This piece is about 45 cm in diameter and weighs nearly three kg. It was a return gift from a wedding in 1911. The inscription in Urdu names the person who got married: “Eknath Pershad, grandson of Nand Lal.”

This necklace was made in the early 20th century for the family of H. Ram Lal. The tanmaniyaan style is popularly found in the jewels of the Nizams and is elaborately adorned in many more layers. The white pearls are from Basra in the Persian Gulf and are known for their high quality and smoothness. The green gemstones are emeralds.

Ram Lal was a secretary in the Nizam’s administration. He went on to become one of the first officers of the Indian Administrative Service after India gained independence. My mother-in-law, Devika Rani, daughter of Ram Lal, inherited it from her mother, and she gifted it to me when I got married.

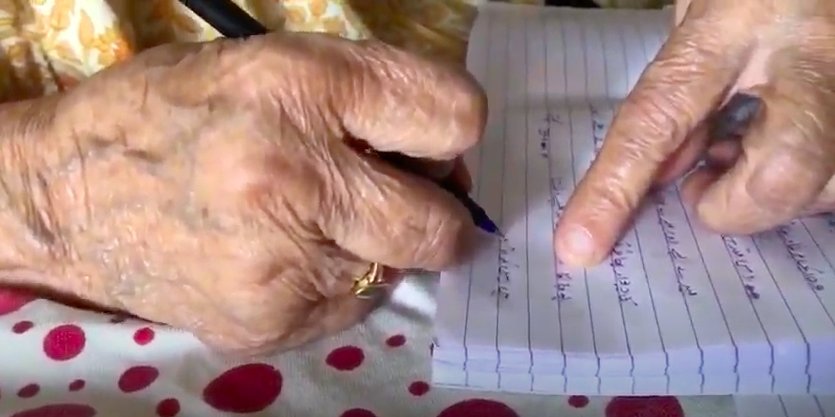

Kusum, my 86-year-old mother, has been translating the work of her spiritual guru Sri Sri Ravi Shankar for several years now, working from her wheelchair every day after breakfast.

My mother studied in Mufeed-ul-Annam school where Urdu was her language of education. She has been a government school teacher and taught social studies in Urdu and later retired as principal of Punjagutta Government High School, Hyderabad. Iqbal, Faiz, and Ghalib were names I grew up listening to and their poetry she recited from memory as she went about her life in Hyderabad.