Chinese community in India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Chinese community

(From People of India/ National Series Volume VIII. Readers who wish to share additional information/ photographs may please send them as messages to the Facebook community, Indpaedia.com. All information used will be gratefully acknowledged in your name.)

Cantonese, Hakkan [West Bengal]

Surnames: Changhing, Cheng, China, Lee, Ming, Ssung, Ta, Yue [West Bengal]

Kolkata

The Chinese community

December 10, 2006

The palm leaf fan

Stories about the Chinese community in Kolkata and the challenges of multiculturalism.

Kwai-yun Li describes the union of two Chinese families living in Kolkata, India, in the 1940s

When the Hakka Chinese immigrated to Kolkata, many of them settled into the shoe-making and leather-tanning businesses. My father took up the shoe business. I remember him as a big person with a loud, belly-quivering laugh, and hair cut close to his scalp so that he looked as though he were wearing a black brush, and he seemed to be always chortling, always drinking chai with friends.

Mother was as different from Father as black is from white. She spent most of her time in the kitchen, cooking for Father and any of his friends who happened to drop by. Mother’s thin shoulders were hunched over her stomach, which had grown big and distended due to the many pregnancies. I don’t remember her ever raising her voice. She seemed to be always looking at somewhere we could not see, and listening to something we could not hear.

A year after he stepped off the ship at Kidderpore, Father opened his first shoe shop, Sam Hin, at 85, Bentinck Street. Two years later, he opened his second shop at 86, Bow Bazaar Street. Three years later, he opened his third shop at 26, New Market.

The summer of 1942 was hot and dry, the monsoon late in coming. Kolkattans chose between sleepless nights indoors, drenched in sweat, and sleepless nights on rooftops and verandahs, plagued by mosquitoes and flies.

Mother sat outside Sam Hin with a glass of lassi and a palm leaf fan. She waved her fan at Mrs Wong, sitting outside her shoe shop, Yun Fa, with her five daughters. Mrs Wong waved back.

Bentinck Street, a narrow cobbled road, linked the business district of Bow Bazaar with the shopping district of Chowringhee. That afternoon, cars, trucks, rickshaws and trams had jammed Bentinck Street. Vendors wandered beside cars, selling sugarcane juice, boiled potatoes, cucumber in masala, roasted peanuts. Beggars wandered between the cars, stopping to beg for coins and food.

Mother waved the fan in front of her face. A mosquito darted and bit behind her ear. At this point Mrs Wong called out, “Come over to this side of the street. It’s cooler.”

Mother meandered through between honking cars, rickshaws and the Park Street tram to reach the opposite side. One of Mrs Wong’s daughters got up, moved her stool closer to Mrs Wong, and said, “Aunty Li, please take a seat.”

“I wish the rain would come,” Mrs Wong said. “The news on the radio this morning said that two rickshawallahs died of heatstroke yesterday.”

“Well, it would be cooler. But think of all the washing that will rot on the clothes lines.”

“Yes. There is that.”

Mother looked at the five Wong daughters. “Hey, you know what?” she said. “One of your daughters would be perfect for my son. Lin is eight years old. I should really find a wife for him.”

“Your eldest is such a good-looking boy. Hmm. I would like that.” Mrs Wong nodded. “Why not? Which of my daughters would you like?”

The five Wong daughters sat in a row, fanning themselves. They giggled when Mother walked over to them. Mother looked at each girl and thought out loud. “I would like my grandchildren to have nice noses. I want them to have bridges between their eyes.” She touched her nose. “Not flat like mine. Your daughters have nice, fair skin. Good, good. My grandchildren will be fair also.”

Mother examined the five noses again and pointed to the third daughter, six-year-old Yun, who had given up her seat for Mother. “I want her.”

Mrs Wong nodded. “All right. She is yours. I will speak to my husband tonight.”

Mother spoke to Father. Mrs Wong spoke to Mr Wong. Father and Mr Wong spoke over cups of tea and plates of beef curry and chapattis at Nizam’s.

Mother and Mrs Wong made offerings at the Ti Hui Mu (Earth Mother Goddess) temple to ask for her blessing so that Lin and Yun, when they were married, would have many sons. Mother and Mrs Wong also went to the Moi Kong, the Buddhist temple near New Market, and made offerings to the Buddha, Amitabha, the Bodhisatva of the Western Heaven, and Kwan-yin, the Goddess of Mercy.

The resident monk at Koi Kong looked up the Chinese almanac and chose a date for the adoption.

Father paid for a Saturday and Sunday announcement in the Chinese Daily:

Mr and Mrs Wong Po Chu wish to announce to the community that from the 16th day of the third Lunar Month of 1942, our third daughter, Si Yun, will reside with Mr and Mrs Li Hu Tai. When Si Yun comes of age, she will marry their eldest son, Li Lin Hoi. Mrs Wong and I will not interfere with Si Yun’s upbringing, nor will we be responsible for her upkeep.

Mother cut out the newspaper announcement, wrapped it in oiled paper, and stored it in the safe together with all the passports, birth certificates, immigration papers and lease agreements for the shops. She pasted another cutting on a piece of cardboard and displayed it under the family altar.

A month later, Father and Mother reserved the second-floor banquet room of the Au Chu Restaurant. They invited one hundred and fifty guests, mostly the Li uncles and aunts, who came from the same village as Father in China, and the Wongs, who came from the same village as Mr Wong. Mother planned the menu with Mr Chen, the owner of Au Chu Restaurant.

Father borrowed money from Tai Qui, Mother’s brother, to pay for the banquet. “Lin is our eldest.” We can’t appear to be stingy,” he said and patted his stomach. “We must have whole roasted pig, we must have duck, we must have fish and shrimps, and don’t forget the beer. Get some whisky, too. I want everyone to be happy for us. It’s not every day that I acquire a daughter-in-law.”

Mother sighed. She spoke to Mr Chen and expanded the menu from eight women’s and children’s tables near the kitchen and five tables for men near the windows. Children ran around the women’s tables. They munched on shrimps and dumplings and spilled coke and root beer on the floor.

Yun sat with Mother, Mrs Wong, three Li aunties, Grandmothers Liu and Li, and two Wong aunties.

At the men’s tables, glasses clinked. Beer and moonshine flowed. The Li and Wong uncles toasted Father and Mr Wong. The men yelled out dirty jokes. The women gathered up the children and confined them to the women’s side of the room.

Four hours later, Mr Chen and his two servants carried Father, Mr Wong, and six other Li and Wong uncles onto the couches in the back room of the restaurant. Mother paid extra for Mr Chen’s servants to clean up all the vomit from around the men’s tables.

Mother, Mrs Wong, Aunty Yee, and Aunty Ai packed the left-over food into aluminium canteen boxes. The Li and Wong children carried the canteen boxes to Sam Hin. Mother invited neighbours for dinner.

When Father and Mr Wong staggered back to Bentinck Street later that evening, Yun had moved across the street with her belongings and had settled into the bedroom with my sister, Nuen.

As Yun grew, Mother taught her to sew and to cook Lin’s favourite dishes.

When Yun was 18 years old, Mother talked to Father. “It is time for Yun and Lin to get married. We are lucky to have such a pretty and docile daughter-in-law.”

“Yes. You are right.” Father sighed. “Pity she is so short. My boy is so tall and handsome.”

Yun married 20-year-old Lin that year. They had five children. All the children have fair skin and dainty noses, but only two of them grew above five feet tall.

Excerpted with permission from

The Palm Leaf Fan & Other Stories

By Kwai-yun Li

Tsar Publications, P.O. Box 6996, Station A, Toronto,

Ontario M5W 1X7, Canada.

www.tsarbooks.com

108pp. $18.95

Kwai-yun Li was born in Kolkata, India, and settled in Canada after an arranged marriage. She is the co-author of A Kiss Beside the Monkey Bars, a collection of short stories.

2019/ Voting in elections

Subhro Niyogi, May 20, 2019: The Times of India

Kolkata’s ‘Chinese’ voters get inked for the first time

Kolkata:

The Indian Chinese community emerged from decades of cocooned existence in Kolkata to vote for the first time in an Indian general election in large numbers.

“We’ve remained isolated from the voting process for too long. It’s time we staked a claim in the development and how India shapes in the future,” said Jordan Lee, who had queued up at Bhagaban Chandra Khatik Primary School on Monday with wife, Susanne, and son, Kenneth, to vote for the first time.

They proudly displayed their inked index fingers after exercising their right.

Residing in the city for nearly two centuries, Chinese have been synonymous with multiple trades like shoe-making, dentistry, beauty salons, and restaurants serving Chinese cuisine. But they have been largely alien to the democratic process of India. Community elders point out that they are culturally alien to the concept of democracy, their forefathers having migrated to India when China was under imperial rule. The tales they’ve heard and passed on are of an Oriental mystical land.

“Most of the elders in the community — our grandparents — did not have Indian citizenship and held Chinese passport. The next generation — our parents — lived in Kolkata all their life but didn’t integrate with the society beyond doing business. Political parties also did not court them. Arrests during the 1962 Indo-Sino conflict made them wary and suspicious. They retreated further into a shell. It is only the next generation — us — who have realised that we cannot continue to live like recluses. From a population of around 20,000 four decades ago, we are down to 4,500 in Kolkata. If we must survive, we must open up, and engage with the outside world. Participating in elections and exercising our legitimate right is a significant step to engaging with society,” said Chen Chien Hou, after casting his maiden vote at 45.

Some members of the community began engaging with the local councillor around a decade and a half ago and, subsequently, voted at the civic and state elections in small numbers. The participation did result in a visible change. “Earliercriminals ruled the roost after dark. No taxi would ply here after sunset. There were no streetlights, the streets were potholed. Encouraged by the change, nearly every Indian Chinese eligible to vote has decided to step out this time,” recounts Joseph, who managed a Trinamool Congress camp that handed out voter slips to members of the community.

While Tangra comes under Kolkata South constituency, old China Town or Teretti Bazaar comes under the Kolkata North seat.

Mumbai

Mumbai: belonging, atavism and globalisation

The Times of India, Nov 03 2015

Mumbai's 3rd generation Chinese eye global jobs, learn Mandarin

Anahita Mukherji & Mithila Phadke

Ernest Wu's grandparents were the first generation to move to Mumbai from mainland China in the 1940s. The city's minuscule Chinese population, estimated at around 4,000.

“Mera chehra dekh ke price mat bolo,“ says Sylivia Chang, an interior designer and mother of two, while shopping on Mumbai's streets. Many , like Sylvia, have lived in India for generations.She speaks English, Hindi, Marathi, Gujarati and a bit of Bengali. But her features ensure she's routinely called Nepali or North East Indian.“I get to skip queue in government offices as they think I'm a foreigner. They are surprised when I start speaking Hindi,“ she laughs.

A bid to connect with her roots is part of the reason she recently joined Mandarin classes in Mumbai conducted by Inchin Closer, an India China language and cultural consultancy . But sentiment isn't the only inspiration. Like many Indians, she hopes Mandarin will give her a competitive edge in the global job mar ket, where China is an important player.

“I'm currently working at an IT start-up that collaborates with a Chinese manufacturer. I recently attended a job expo in Mumbai attended by many Chinese, one of whom began talking to me in Mandarin. I couldn't understand what she was saying. I wish I did,“ says Kitlin.

While Kitlin speaks a smattering Hakka, native to the South China region her family comes from, Sylvia speaks Hupeh, another provincial Chinese language. Both feel Mandarin, like Hindi, would give them access to much larger swathes of the country .

Wu, general manager at Hard Rock Café is keen to learn his mother tongue. Over the last few years, he felt the need to discover his heritage and is now trying to find time out of his hectic schedule to learn Mandarin. Mazgaon resident and chartered accountant Lisa Chung began learning Mandarin after being admonished by garrulous grandpa Liao next door for not knowing how to write her name in her mother tongue. The 28-yearold began learning basic spoken Mandarin as well as the script from him.

Chinese-Tamil Cross

Halting in the course of an anthropological expedition on the western side of the Nīlgiri plateau, I came across a small settlement of Chinese, who have squatted for some time on the slopes of the hills between Naduvatam and Gudalūr and developed, as the result of alliances with Tamil Pariah women, into a colony, earning a modest livelihood by cultivating vegetables and coffee.

The original Chinese who arrived on the Nīlgiris were convicts from the Straits Settlement, where there was no sufficient prison accommodation, who were confined [99]in the Nīlgiri jail. It is recorded that, in 1868, twelve of the Chinamen “broke out during a very stormy night, and parties of armed police were sent out to scour the hills for them. They were at last arrested in Malabar a fortnight later. Some police weapons were found in their possession, and one of the parties of police had disappeared—an ominous circumstance. Search was made all over the country for the party, and at length their four bodies were found lying in the jungle at Walaghāt, half way down the Sispāra ghāt path, neatly laid out in a row with their severed heads carefully placed on their shoulders.”

The father was a typical Chinaman, whose only grievance was that, in the process of conversion to Christianity, he had been obliged to “cut him tail off.” The mother was a typical dark-skinned Tamil Paraiyan. The colour of the children was more closely allied to the yellowish tint of the father than to that of the mother; and the semi-Mongol parentage was betrayed in the slant eyes, flat nose and (in one case) conspicuously prominent cheek-bones.

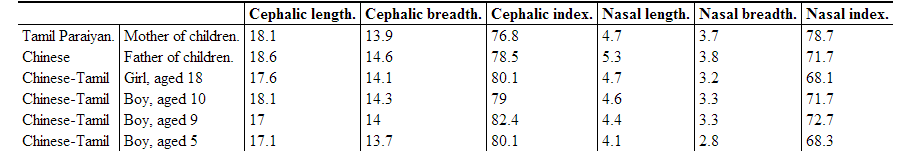

To have recorded the entire series of measurements of the children would have been useless for the purpose of comparison with those of the parents, and I selected from my repertoire the length and breadth of the head and nose, which plainly indicate the paternal influence on the external anatomy of the offspring. The figures given in the table bring out very clearly the great breadth, as compared with the length, of the heads of all the children, and the resultant high cephalic index. In other words, in one case a mesaticephalic (79), and, in the remaining three cases, a sub-brachycephalic head (80.1; 80.1; 82.4) has resulted from the union of a mesaticephalic Chinaman (78.5) with a sub-dolichocephalic Tamil Paraiyan (76.8). How great is the breadth of the head in the children may be emphasised by noting that the average head-breadth of the adult Tamil Paraiyan man is only 13.7 cm., whereas that of the three boys, aged ten, nine, and five only, was 14.3, 14, and 13.7 cm. respectively.

Quite as strongly marked is the effect of paternal influence on the character of the nose; the nasal index, in the case of each child (68.1; 71.772; 7; 68.3), bearing a much closer relation to that of the long-nosed father (71.7) than to the typical Paraiyan nasal index of the broad-nosed mother (78.7). It will be interesting to note hereafter what is the future of the younger members of this quaint little colony, and to observe the physical characters, temperament, fecundity, and other points relating to the cross breed resulting from the blend of Chinese and Tamil.