Lahore: F-K

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

General Post Office

The Post-Colonial Hangover

Text By Issam Ahmad And Photos By Ayesha Vellani

Built alongside the YMCA building in 1887 to commemorate Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee, the imposing yet elegant arches of Lahore’s General Post Office (GPO) represent a prime example of colonial era Indo-Saracenic architecture.

It blends British, Hindu and Mughal design elements, and took its current shape when it was established as the Post Office, replacing the telegraph office of Anarkali Bazaar. According to eminent Lahorite Majid Sheikh, the bell from the original building was taken from it and transplanted in the GPO for continuity’s sake and as a symbol of good luck. The GPO's inauguration coincided with the unveiling of clock towers and monuments throughout India.

Nadeem Ahsan, current Chief Post Master, says: “The GPO brings forward a tradition of grandeur as one of the traditional beautifying flanks of Mall Road”, alongside the Lahore High Court, the Punjab University, Kim’s cannon, the National College of Arts and the Town Hall.

The building consists of two main halls and two minarets, as well as the commemorative stamps bureau responsible for promoting Pakistani culture, heritage, flora and fauna. It is the largest post office in Pakistan, handling a daily average of 20,000 deliveries per day with a staff of 3000. On token tax and pension payment days, the number of visitors can swell to 5000.

Though steeped in tradition, Pakistan Post is not oblivious to the needs of modernity and recently implemented an automated counter system enabling all customers to make use of services from one counter.

According to Ahsan, the advent of the Internet age saw a “small decline” in the volume of private mail, though with the increase in commercial mail the Post Office remains a revenue generating department.

The GPO was also the site of one of the worst suicide bomb attacks to hit the city of Lahore when on Jan 10 this year, a bomb ripped through GPO Chowk, disrupting a lawyer’s rally and killing 25 people. Fragments of the suicide bomber’s body were later found on the upper portions of the GPO though the building itself suffered little structural damage.

In addition to mail services, the GPO also deals with Baitulmal (charitable) programmes. It is lit-up yearly on August 14 and on October 9, World Post Day, the flag of the Universal Postal Union is hoisted alongside the national flag as part of they day’s celebrations.

Heera Mandi

June 25, 2006

REVIEWS: No happy endings

Reviewed by Noor Jehan Mecklai

A BEAUTIFUL young British researcher sets out to write, over a four-year period, an academic report on the history, culture, lives, aspirations, cruel disappointments, social stigmatisation and so on of the people of Heera Mandi, Lahore. She weaves her story principally around the household of Maha and her daughters, becoming so deeply involved in their daily heartbreaks that by her own admission she loses her professional moorings. This accounts partly for the colourful vigour of her style, compared with that of Fauzia Saeed in her famous Taboo. But it is unfair to compare these two books. Wait till Louise Brown gets around to publishing her actual academic report. Both books are testaments of caring, though whereas Fauzia was warned not to take up temporary residence in the area, Louise takes a room there, eventually moving in with Maha.

Whether written in a graphic, a strictly factual or an ebullient manner, Louise Brown’s revelations may elicit tears of pity and compassion, or they may raise anything from a titter to a belly laugh. Or since she really tells it like it is, one may even laugh and weep at the same thing, as, for example, when Mota, the fat, middle-aged lover, is supposed to come courting teenaged Nena, or when Maha simply cannot understand that Louise could spend an evening merely conversing with a man. But laughter flees as the pitifully young Nena is shipped off overnight to the Gulf as a concubine for a wealthy Sheikh, owing to her family’s desperate financial position. The inexorable decay of Maha’s looks and figure, exacerbated by that of her marriage, are killing the demand for her services.

However, the lively descriptions of so many things, such as the excited village family packing their shoddy finery for a successful three-month contract in Dubai, the urs of a saint, or of the train journey to Sehwan Sharif, always with an eye to the main theme, somehow prevent one’s interest from flagging, as it would have done with less relief from the filth and degradation of the lifestyle portrayed.

The salons of the best tawaifs of old, and the glamorous homes of successful mohalla women, taken by their ‘husbands’ to posh suburbs, contrast starkly with the cruelty and ignominy of Maha’s ouster from a more ‘respectable’ neighbourhood

Then there are the clever contrasts, such as that between the little girl in the church at Roshnai Gate, “so lovely and fresh, and so unlike the other girls in Heera Mandi, who are miniature women at the same age”, and Nena receiving lessons in the art of seduction from her mother. Similarly, the salons of the best tawaifs of old, and the glamorous homes of successful mohalla women, taken by their “husbands” to posh suburbs, contrast starkly with the cruelty and ignominy of Maha’s ouster from a more “respectable” neighbourhood when she tries, for the second time, to leave Heera Mandi.

Among the variety of subjects presented, Brown gives vignettes of the hijra society, describing their growing-up problems, their reasons for adopting this lifestyle, and the fate of Tasneem, who transgresses against the rules of this very insecure group by marrying. They too, like the others in the mohalla, are portrayed as multifaceyed human beings.

“I love and hate this place with equal measure,” writes Louise. “It’s both fascinating and loathsome. When I’m away, I’m desperate to return, yet when I’m here, I can’t wait to escape.” Thus, she expresses the consummate dilemma of compassionate researchers like herself in places like Heera Mandi.

The Dancing Girls of Lahore: Selling Love and Saving Dreams in Pakistan’s Ancient Pleasure District By Louise Brown

Fourth Estate.

Available with Liberty Books, Park Towers, Clifton, Karachi

Tel: 021-5832525 (Ext: 111)

Website: www.libertybooks.com ISBN 0-06-074042-6 311pp. Rs995

Jehangir’s Tomb

Jehangir’s Tomb: a reminder of Mughal glory

By Sehar Sheikh

A few days ago, I read the term ‘the Pakistani Mughal’ for the emperor Jehangir in a paper. He was termed as ‘Pakistani’ Mughal because of all the six great Mughals, i.e. Babar, Humayun, Akbar, Jehangir, Shah Jehan and Aurangzeb, only Jehangir is buried in Pakistan. The historical city of Lahore has the privilege of having Jehangir’s mausoleum; the great Mughal Emperor ruled the sub-continent from 1605 to 1627.

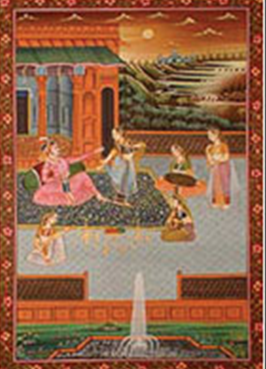

It is believed that Jehangir is in fact prince Salim, the most romantic Mughal prince who had fallen in love with Anarkali, a dancing girl in the Mughal court.

Akbar’s son, Emperor Jehangir, is buried in the magnificent Shahdara Mausoleum near the Lahore Fort. It was Jehangir’s last wish to be buried in Dilkusha Garden of his beloved wife Noor Jehan in Lahore. Noor Jehan’s dark and crumbling tomb also lies in the shadow of her husband’s mausoleum, as she had wished for.

Jehangir’s tomb is considered as the most magnificent structure in sub-continent after Taj Mahal and Qutub Minar. It was designed by Empress Noor Jehan in 1627 who also designed her own and her brother Asif Khan’s tombs. After her husband’s death, Noor Jehan had permanently shifted to Lahore and influenced the design and construction of the mausoleum. It took 10 years to build the tomb and 10 lakh rupees were spent on its construction.

The image of Jehangir’s tomb is also printed at the backside of old 1,000-rupee note of Pakistan.

The mausoleum has four minarets and is situated in a garden full of lush green grass and bushes. Each of these four minarets is 30-metre high and the garden is walled. There are two enormous gateways that lead to the square enclosure known as Akbar Serai. On the west of this enclosure is another area that gives full view of the garden in front of the monument. From the centre of the garden, four parterres proceed which are further subdivided into 16 divisions by means of a brick geometric pavement flanking narrow water channels. Originally there were many enchanting fountains in the four narrow canals which have almost ruined now due to negligence by the department of archaeology.

As you enter the passage from the west which leads to the grave, the corridors and inner sanctuary overwhelms you with splendid mosaic on white marbled walls, floors and ceilings. Not an inch is left unembellished with floral mosaic or Quranic verses. The beautifully laid sarcophagus is screened by a panel of five marble jalis (latticed screen, usually with an ornamental pattern constructed through the use of calligraphy and geometry). The gravestone reads, “Illumined grave of His Majesty, Asylum of Pardon: Emperor Nur-ud-din Muhammad Jehangir, 1037 AH”.

The fourth Mughal Emperor, Jehangir, was very fond of gardens, rivers, lakes, flowers and animals. He had a multitude of rare flowers, birds and animals. He mentions about his love and collection of birds and animals in his memoir Tuzk-e-Jehangiri as well. No doubt his mausoleum has lost a big part of its beauty owing to the passage of time yet it’s a beautiful place that reminds us of the grandeur of our great Muslim rulers.