Lahore: R-Z

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

Lahore: Ramazan

A Buttery Knife Through The Heart

Halima Mansoor explores how Ramazan in Lahore is a feast for the soul as well as the stomach.

The way to Pakistan’s heart is through its stomach. Who can debate that, in more ways than one, the heart of Pakistan is Punjab and undoubtedly Lahore is its big bottomless stomach? While the various ways to interpret that would cause me much entertainment and Lahoris much ire, the most obvious is the link through the gastrointestinal tract!

In Ramazan, this love for food is nurtured with such intricate planning and with such voluminous folds of fat that it almost seems like Ramazan is the month of indulgence rather than abstinence.

A week in advance, special hoardings revisit the streets of Lahore: in an attempt to make them look new and different from last years’, the eateries change the fares, trying to match the recent petrol price hike. Got to keep up with the Joneses, yes they do! If you like burning holes in your pocket, please direct yourself towards these aesthetically misguided cafes, that change names more frequently than their napkins, for a “Ramazan Special with free Iftari and dinner buffet for only Rs799” or similar three digit numbers that actually become four digits, once you do the math with the taxes and soft drinks. Of course, no one would think of including water in the Rs799: who needs water after a day of fasting; fizzy drinks are far more refreshing.

So what makes Lahore so special in Ramazan? If you turn away from the aforementioned billboards and restaurants, you will be lured by the rest of the city, carefully wafting a delicious blend of smells towards you.

All markets are dotted with stalls of freshly fried pakoras of various kinds: stuffed green chillies, potatoes, onions, aubergine, everything mixed, and occasionally spinach. While you can certainly spend the month trying a new stall for each Iftar, the pakoras found in Mazang are undoubtedly the best. Well spiced, with fresh ingredients and an addictive aftertaste begging for more. Consume them on a daily basis and come Eid you will look like a pakora in your Eid attire. A very fancy pakora, but a pakora nonetheless.

Mazang also offers up a plate of fresh, glutinous nihari, a la Lahore. Those originating from Karachi should not look upon it disdainfully, and must try it right after breaking the fast. Thick, sticky and utterly satisfying. While most people have plain nan, try the nihari with their in-house speciality, taftan; a subtly sweeter version of nan. The spicy gravy is not muted with the sweet bread, on the contrary the entire ensemble does justice to your palate!

The view from the Mazang’s rooftop is part of the charm: two floors higher than the rest of the city, it gives you a perfect perspective on the great run for food that occurs in the last three minutes before the sirens blare. Who needs patience and who needs to feel the pain of the poor: just run over anyone who comes in between a fasting man and his food!

If sitting in the comforts of your own home is your Ramazan reprieve, then allow me to introduce you to chaat and dahi bara heaven. There is a shop, at the corner of Wahdat Road and Ferozepur Road that almost beats the Karachi Burns Road Fresco. Pick some up before your Iftar and ask them for extra sachets of the spices and chuntey. Add some Feekay ki lassi from Gowalmandi (Feeka being the name of the gentleman who creates the concoction!), some freshly made jalebi, a banana walnut cake from Pioneer Store and turn on the boobtube for an evening of thoroughly enjoyable lazing. Another speciality straight from Lahore!

For all the complaining about extravagant Ramazan fares, a five-star’s Sehri is by far the most fun. Indulge in it, perhaps once: wake up, put on the Lahori face and waltz into the freezing hotel for a continental Sehri. Their eggs are a personal favourite and the fact that they actually serve Cocoa Crispies is almost cute as it is supposedly a five star- hotel.

Take away the passion for food and Ramazan in Lahore will become unutterably frustrating. The dull haze of the day is emphatically pronounced with its snail’s pace work habits and only broken on the road with angry drivers, who consider the next car as nothing better than road kill. To make Ramazan work in Lahore, embrace the Lahori in you. Feed the stomach. The soul is always redeemable next year!

Lahore: Shalimar Gardens

Splendour Of Mughal Architecture

By Sehar Sheikh

Greenery, enormous gardens, lofty trees and dancing water in fountains entice all and sundry. Beauty of nature appeals everyone and this natural beauty along with the splendour of Mughal architecture is at full play at Shalimar Gardens, situated in the east of Lahore.

Gardens have been an integral part of Mughal architecture ever since Babar who laid down gardens on the bank of River Jamuna. Shalimar Gardens were constructed by Shah Jehan, the great grandson of Babar in 1642 AD. Spread on 80 acres, these gardens were used as Royal pleasure gardens during Mughal period. Basically they were laid down on the plan of a garden in Srinagar (Kashmir) and were built to provide recreation to the royal family whenever the Emperor was on a tour in Lahore. In 1818, the gardens were destructed by the Sikh ruler, Ranjit Singh, and were converted into a stable. The marble that decorated the pavilions of the gardens was taken away to decorate Ram Bagh and the Golden Temple at Amritsar.

During English period, Shalimar Gardens were again opened to the public; however, they had lost a big part of their beauty by then. When Pakistan came into being in 1947, the gardens were restored by the Pakistan government and are open to public since then.

Shalimar Gardens consist of three descending terraces which are elevated above one another. The upper terrace is known as Farah Bakhsh meaning ‘bestower of pleasure’. This terrace was originally reserved for royal family and was planted with fruit bearing trees. The present day entrance to the upper terrace was the resting chamber of Shah Jehan while on the west of the same terrace was situated the residence of the Empress. The middle terrace is known as Faiz Bahksh meaning ‘bestower of goodness’ and the lower terrace is named as Hayat Bakhsh meaning ‘bestower of life’.

Readers would be surprised to know that there were originally about 410 fountains in the gardens. These magnificent fountains discharged into wide marble pools. The water of these mountains cools down the surrounding area and provides relief to the visitors especially during scorching summers in Lahore.

These enormous waterfalls are the result of adept engineering skills of Ali Mardan Khan who proposed to the Emperor that the waters of the Ravi be brought to Lahore to operate the fountains of Shalimar Gardens. His proposal was approved and within two years a 100 miles long canal known as Shah Nehar was completed. The water supply system of the gardens was such an astounding one that even the modern day engineers are unable to understand how the fountains were operated originally. Nevertheless, today the fountains are operated by electricity.

Every year during March, Mela Chiraghan is held outside the walls of Shalimar Gardens. The shimmering lights and beautiful water cascades and fountains present a beautiful sight. In 1981, Shalimar Gardens were declared as a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with Lahore Fort.

The vastness of the Shalimar Gardens, the several species of trees planted here, the enormous mountains and its association with the Mughal rulers make Shalimar Gardens a place worth visiting. So next time you are in Lahore, don’t forget to visit Shalimar Gardens.

Lahore: Sir Ganga Ram and Dyal Singh Trusts’ buildings

Two heritage buildings gasping for life

By Zaheer Mahmood Siddiqui

LAHORE, April 7: No professional inspection of the two heritage buildings along The Mall has so far been carried out to assess the damage caused by the March 11 blast at the FIA headquarters on Temple Road.

The Sir Ganga Ram and Dyal Singh Trusts’ buildings have an aerial distance of 100 meters or so from the FIA offices and tenants say the impact of the blast worsened the (already deteriorating) condition of the pre-partition structures, raised by two philanthropists to whom the city owes a lot. A civil engineer and leading philanthropist of his times, Sir Ganga Ram designed and built the General Post Office, the Lahore Museum, the Aitchison College, the Mayo School of Arts (now the NCA), the Ganga Ram Hospital, the Lady Mclagan Girls High School, the chemistry department of the Government College Lahore (now GC University), the Albert Victor wing of Mayo Hospital, the Hailey College of Commerce, the Ravi Road House for the Disabled, the Ganga Ram Trust Building on The Mall and the Lady Maynard Industrial School.

He also constructed Model Town, once the best locality of Lahore, the powerhouse at Renala Khurd as well as the railway track between Pathankot and Amritsar.

A great philanthropist who supported all good causes, Sardar Dyal Singh Majithia was among the first 10 members of the Punjab Public Library. He still lives on through his generous legacy, which enabled the establishment of the Sardar Dyal Singh Trust Library and the Dyal Singh College in Lahore besides the Majithia Hall on Empress Road that now houses the Haji Camp.

The Tajdeed-i-Lahore Committee, constituted in 2000 to take up restoration of some of the old buildings on The Mall and the adjoining streets to their original architectural splendour, merely carried out repairs of the front portions of the two buildings and that, too, at the expense of the tenants but ignored the rear parts.

A number of tenants living in the rear of the two buildings claimed that the two structures had never been repaired. “Several government departments’ officials arrive whenever anyone of us starts renovation or repair of any part of the buildings on our own. Even we are issued eviction notices, though we are regularly paying the rent on time,” a tenant, Shahid Chaudhry advocate, told this reporter.

Governor Khalid Maqbool took personal interest for the restoration of the tenancy of Shezan restaurant at Dyal Singh Mansion that was burnt by rioters some years ago, he added. “The governor should now intervene and prevent the situation from worsening,” the lawyer demanded.

Lahore: Tollinton

Lahore: Tollinton Market

Memorable market

By Yasira Naeem Pasha

Tollinton Market in Lahore has great historical significance, but is suffering from official neglect

Tollinton Market in Lahore has a great historical and cultural background. Originally there was no particular name given to the structure, save for its exhibition hall. It was after a long time that it was given a proper name, Tollinton Market, after one of the government of Punjab’s officials, Sir H.P. Tollinton.

The old Tollinton Market used to be situated on one side of Shahra-i-Quaid-i-Azam, behind the famous museum, facing Anarkali Bazar. Its two sides faced two different roads.

The construction date of the old Tollinton Market building is not known. Some facts reveal that it was not actually made for the purpose which it serves today. The fact that in the past it was ignored badly and treated callously disappoints many. The building is a typical colonial structure. Most of the historical events confirm its use in the colonial period and afterwards.

In the 19th century the world witnessed some revolutionary changes. People started sharing local products with the rest of the world. Different kinds of exhibitions were also being held. This gave birth to the famous Industrial Revolution throughout Europe and America.

Back then, the subcontinent was ruled by the British. Whatever the British thought of in those days would be implemented in the area they’d occupied. So surveys were conducted for selecting the site for holding exhibitions. The site selected originally must have been part of the garden surrounding the Wazir Khan Pavilion, which was later made into the Punjab Public Library. It was on these large gardens where Ranjeet Singh camped when he came to capture Lahore 200 years ago. Subsequently many important buildings were constructed. A good example of such buildings is the Telegraph Office that used to display a marble plaque which proved that we had a telegraph system in place as early as in 1858. The sad part is that some years back the office was demolished.

In 1861, plans were being made to hold an industrial exhibition in Punjab at Lahore. In 1863 Mr Bains, resident engineer of the Punjab Railways, prepared the design for the building where exhibitions would be held. The first Punjab exhibition was inaugurated on January 20, 1864, by the then governor Sir Robert Montgomery.

The exhibition went on for some years but then the building was considered a perfect place for an art school. As a result, a school was founded in 1876 while the main pavilion continued to serve as a museum till 1894.

In 1887, it was decided that the building should be converted into a fruit and vegetable market for the elite of the town. This reveals that the area was liked by the British who wanted to develop their own community in the region having all the facilities like offices and small shops. The revised plans were submitted on July 25, 1895 and were approved by Rai Bahadur Gangaram (executive engineer). In 1911, a beef market was constructed here and in 1920 repair work was done. Another term of repair work was undertaken in 1937.

In 1920 the building was thoroughly repaired and the projecting entrances along the northern side, i.e. parallel to the Mall Road, were demolished to facilitate the service lane. The building suffered a callous blow just in the name of serving the public.

Afterwards, Tollinton became a proper market. Seafood, mutton, beef, vegetables, fruits, canned food and groceries could be bought from here. It was the beginning of the market but the end of the original form of the building.

According to the Lahore Conservation Society, “With a powerful sense of history, academic atmosphere, low density and large trees the precinct of Tollinton Market captures that special flavour of urbanism that is identified with Lahore. Conservation of the quality and character of spaces is not limited to preserving buildings of historical or architectural value but includes the control of land use, building densities and heights, nature of traffic. As such the development of multi-storey car park and a high use of commercial buildings on the site of Tollinton Market will prove to be a thin end of the wedge that will end up destroying everything we hold of value not only in this particular precinct but in the city of Lahore as a whole.”

Then the emotional aspect of the situation cannot be ignored either. As Sir Pran Neville an old resident of Lahore, says, “Being emotionally attached to my beloved Lahore, I am deeply disturbed to learn about the present plan to demolish the Tollinton Market Building, the historic and the prominent landmark of Lahore which housed the first Punjab Exhibition in 1864. No other city can boast a more stirring and cheered history than Lahore, the gate way to the subcontinent. It will indeed be a great pity to demolish this glorious structure built by British rulers but with the labor of nameless artisans and workers of Lahore.

We should make a fervent appeal to the authorities to preserve this landmark at all costs. I have seen how other nations take pride in their national heritage and with painstaking efforts struggle to re-build their historic structures destroyed by nature or by war. The polish people worked for decades to rebuild the old town of Warsaw completely destroyed during the last war. They had to refer the old photographs of the senior citizens.”

Lahore Tollington

April 30, 2006

EXCERPTS: If these walls could talk

Nukta Art is a bi-annual Pakistani art magazine

Samina Shah writes about the revamping of Tollington Market as a museum for Lahore

IN living memory, the building often referred as “Tollington”, has been a provision market. In fact it has been the main market for a long time for household products, and since it stands close to the Punjab University, the National College of Arts (NCA), and a host of other educational institutions, generations of students remember it with nostalgia.

This edifice stands at the intersection of two axes, and the north to south alignment is from the old city of Lahore and the British cantonment, and the east to west is the old and new Anarkali bazar. Seen in the context of the colonial British policy for arts and industry, in 1864 the Tollington building was erected to house an exhibition of Indian crafts — an event that was immensely popular and continued for a period of nine months.

Looking at the chain of events as a sequel to this, the building housed antiquities and by the end of the 19th century it became the birth place of the Lahore Museum and later the NCA.

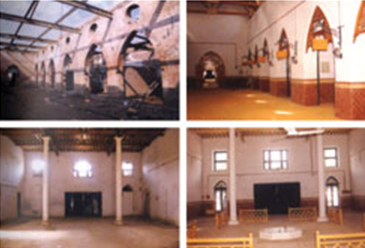

Meanwhile, during the First World War, Tollington fell into neglect. A few years later it found its fortunes turning when at the end of the war the British administration began to attend to civilian matters. Giving Tollington a new look in 1922, Sir Ganga Ram was given the charge for its restoration and repair work, and it was then that a flat one replaced the slanting wooden roof.

However, for the curious student of architecture (and the general public), one interior wall of the present building has been deliberately left bare, that is, kept without plaster, to facilitate the observation of different stages of masonry and structure. The size of the brick varies as the walls go up, since in those days there was no concept of protection against dampness. But recently the restorers of this building have carefully made the entire walls damp-proof by working at the base of an already built-up formation.

The building is in three sections: the main entrance hall, that is the waiting area, has benches of the same period and a fountain in the centre. The commercial building area, which used to have the fruit and vegetable market, has rows of open quarters as “one shop one craft” on both sides. Each room has a metal spiral staircase that goes up on the first floor of the same room as a loft for storage or book-keeping. The metal work is 19th century customised; the display boards outside each “shop” are ready as nameplates, described aptly in the novels of Somerset Maugham.

Proceeding with the renovation and restoration, Sajjad Kausar, the architect who has spared no pains in bringing this building to completion, says: “If the re-use of the building is close to the original, then the intervention is minimum, as making it better-looking or demolishing it is not restoration. In the building today, 1864 and 1922 have been cleverly combined.”

He is overly protective of his work, and so are his colleagues and advisors architects Nayyar Ali Dada and Kamil Khan Mumtaz — among others, who have closely followed its progress. “There is no place in Lahore for showcasing local crafts like the Covent gardens displays of the English crafts or the New Delhi State Emporium, which is a huge establishment for Indian crafts. The state ensures a price control, thus enabling the craftsmen to sell their products and attract tourists at the same time. I have restored this structure keeping in mind the need for a crafts bazar. There is a foyer in the centreand a Display Hall for two and three-dimensional exhibits. In short, I am looking at a Tollington Museum, which encompasses the above,” says Kausar.

Mumtaz adds that “this was an interesting case, as some of the issues faced were authenticity vs reconstruction for adaptive reuse, and because the intervention is to be minimal, restoration comes as the last choice. When we look at the patinas of history, questions like what to restore, and which period of history one restores it to, come up. These are all debatable issues, and should bring about more deliberations amongst professionals as such issues do not have readymade simple answers; they need brainstorming and discussions.”

This building is a landmark of Lahore and because it fell into an era of descent, the developers got involved and wanted to make it into a commercial venture. To do so they needed to demolish the structure, but later, after much protest, they changed their decision and were ready to re-make it into its original form. This brought the “Tajdeed-i-Lahore” at the helm of affairs along with the PHA, who have taken the “Tollington Market’ project as part of a larger scheme of conserving Lahore’s built heritage.

“Conservation is not a sentimental journey, as cultural heritage is a document that has to be maintained in all honesty; if that is not followed scientifically then everything is reduced to fantasy,” reiterates Mumtaz. “The building is complete now; but what they plan to do with it is up to the administration.”

Regarding the future of this building and its usage, the senior officials of the Lahore Museum and PHA are still deliberating and are unable to give any answer. However, some concerned citizens are enthusiastic for the establishment of a city museum.

“What is needed is a museumologist to take the work on from here. This building can have sections like a hall of fame, Lahore’s history through the ages, the sacred sites, shrines, gardens, religious places like temples, gurdawaras, mosques, life styles, etc.,” says Faqir Saifuddin, the director of the Faqir Khana Museum. “I have given guidelines of how to go about it to the Governor of Punjab. Let us see what happens eventually,” he reflects.

There are plans for developing the meat market area into an area of folk culture with the open spaces being utilised for folk music, puppetry, and the performing arts, thus making the Tollington Museum really come alive after more than a century of neglect and apathy.

Excerpted with permission from: Nukta Art Edited by Niilofur Farrukh Available from Flat # 104, 2nd floor, 11/C-9th Commercial Lane, Zamzama, Clifton, Karachi Fax: 021-5845815 Email: nuktaart@yahoo.com 142pp. Rs520

Niilofur Farrukh is the author of Pioneering Perspectives, the first book on art by a Pakistani woman, as well as an art critic. She is on the advisory council of the Pakistan National Council of the Arts and is the president of AICA Pakistan — the Paris-based International Art Critics Association Samina Shah is an art critic based in Lahore and freelances for various publications.

Walled city

The legends of the walled city

By Intizar Hussain

WHILE going through Majid Sheikh’s book Lahore-Tales Without End I was reminded of a Persian saying ‘Agar pidar natuwanad pisar tamam kunad’ (what had been left unfinished by the father was carried to a finish by the son). Indeed Majid Sheikh is the proverbial son who reminds us of his father Hamid Sheikh, a renowned journalist of his time.

While in Pakistan Times and later in Civil & Military Gazette where he acted as its Editor, he in his columns was seen probing into the past of the city of Lahore. Each street and every koocha of Lahore, as depicted by him, appeared trailing with a magical past behind it. Now we know from Majid Sheikh that he was very keen to bequeath this legacy to his sons.

“In our childhood years,” he says, “we would listen to his stories with rapt attention. We never knew when or where he crossed that thin line between a fib and reality... to add to his passion for storytelling. He would often take me on long walks through the narrow lanes of the old walled city of Lahore. On the way he would point out where people lived and what they did.” And he adds informing us, “Most of what I have to say in this book, I have picked up from where he left off… in 1971.”

So these columns dealing with the city of Lahore ask for being read in continuation of what Hamid Sheikh has already written and deserve to be collected under the title, ‘Lahore as discovered by a father and a son’. However, here we have only the son’s columns collected under the title Lahore – Tales Without End. While still a child, his father would take him on long walks through the narrow lanes of the walled city. Now he has grown in years and needs no father to guide him. He, in his independent capacity, is seen roaming in the winding lanes and alleys of the walled city and stopping at the corner of each lane in expectation of finding a sign which may lead him into the past of that lane. Such signs are very much there, facilitating his journey from the present into the past.

Journeying in the past of this city the researcher stumbles on a mound which guides him toward prehistoric times. Guided by a legend popular with academics, Majid Sheikh arrives at the conclusion that it was here on this mound that Sitaji had found asylum during her second exile, and it was here that her son Lahu was born. As the legend goes, the name Lahore is derived from his name. Majid Sheikh goes to the extent of pinpointing the spot where this mound was situated. He refers to the version, according to which this mound was located on the spot being now within the Lahore Fort “just next to where the road curls upwards from Haathi Darwaza.”

This legend helps him to trace the origin of Lahore in antiquity, roundabout BC5000 according to his estimate. Don’t dare ask for historical evidence. Prehistoric events don’t stand obliged to historical evidences. Where is the historical evidence for events in Ramayana?

How wonderful that Majid Sheikh in his research has the dexterity to save himself from all the travails a researcher in antiquity has to pass through. He just takes a round in the lanes of the walled city, chats a little with old people and taking cue from them makes a long jump in mythic times, where he finds Sitaji residing on a mound, Valmiki composing Ramayana, and rishis engaged in recording vedas; and all this happening within the confines of Lahore. Then comes a time when Majid Sheikh finds Lahore sending the message of Buddhism to all nooks and corners of the subcontinent. Chandr Gupt Moriya and his grandson Ashok were, according to Majid Sheikh, Lahoris.

Then soon we are ushered in historical times. But the city is still seen carrying a sense of mystery with it. Who were the six pious bibis buried in the graveyard of Bibi Pak Daman. Researchers have not been able to determine who they were. But the faithful have faith in the legend, caring little what the researchers say. According to the legend, the leading lady known as Bibi Haj was Hazrat Ali’s daughter Ruqayya who, with a group of ladies, reached here after the tragedy of Karbala.

And who lies there in the tomb underneath the dining hall of the Governor’s House? A saint or a sinner? The researchers have so far failed to determine who the man is. So it remains a mystery.

And who is the child-saint, whose tomb in the vicinity of Madho Lal Husain is known as the shrine of Ghorray Shah. What is the origin of the popular myth that “if one brought the child-saint his favourite pastime horses, be it real or be it simple mud-baked ones, any wish made at his shrine is fulfilled.”

Again, who was Syed Garazoni, popularly known as Miran Badshah, whose grave lies in the basement of Majid Wazir Khan. And what is the legend associated with what is known as Syed Garazoni’s curse. All this points to the fact that the city of Lahore, I mean the walled city, abounds in tales and legends which goes to make it a typically traditional city.

If you are after historicity, please refer to Syed Noor Muhammad Chishti, Muhammad Latif, and Kanhiya Lal. Majid Sheikh is a storyteller. He seems thinking that a city can better be understood through the tales, legends and superstitions surrounding it. Even the historical events he refers to seem turning in his hands into fantastic tales. Here is a portrait of old Lahore he has presented with the help of legends and tales collected from the lanes and alleys of the walled city. And what a fine living portrait.

Lahore: Wazir Khan Mosque

Wazir Khan Mosque

By Sehar Sheikh

The 12 gates of Lahore hold a number of historical buildings inside them. These include mosques, havelis, hammams (public baths), bazaars, tombs and temples. Negligence on the part of successive rulers of sub-continent, consecutive selling and then demolition of structures by their new owners, encroachments inside the bazaars and many other factors destroyed most of these centuries’ old constructions. Only a few have withstood the ravages of time and even fewer manifest their glorious past through their relatively intact architecture. Wazir Khan Mosque situated inside the Delhi Gate is one of them.

Wazir Khan Mosque is unique in its architecture from other famous mosques of sub-continent built during Mughal Period because it reflects a blend of Persian and Indian styles of architecture. It’s the second most spacious mosque of Lahore after Badshahi Mosque. Wazir Khan Mosque is situated in a crowded bazaar of the old city. The towering minarets of the mosque catch the sight of the visitor/worshipper from a long distance. This mosque was built by a Hakeem (physician) Ilmuddin Ansari also known as Nawab Wazir Khan, a title bestowed on him by Emperor Shah Jehan. Later, he became the Governor of Lahore. Wazir Khan was very fond of public welfare projects. So he sponsored the construction of several hamams, bazaars, palaces, gardens and shops, most of which have now perished. He laid down the foundation of Wazir Khan Mosque in AD 1634. For some time this mosque served as imperial Jamia Masjid where Mughal Kings and courtiers would offer their Friday prayers. After the construction of Badshahi mosque, the title of imperial mosque shifted to it.

Entering through the main gate of the mosque, one has to climb a number of steps and then pass through a spacious but covered courtyard. Four small and one huge dome are offset by two octagonal minarets on both sides. There is a shrine of Syed Muhammad Ishaq better known as Hazrat Meran Shah on the left of the courtyard. Hazrat Meeran Shah was a Sufi saint from Iran who settled down in Lahore during the reign of King Feroze Tughlaq. This tomb was built before the construction of Wazir Khan Mosque.

Walls and floor of the mosque are built with red bricks. The pattern of bricks on the floor makes an eye-catching symmetrical design. The walls are plastered, coloured and entirely covered with arabesque painting and shimmering tiles, and the inlaid pottery decorations and panelling of the walls are vivid and glowing. Exquisite floral decoration in a unique cut tile mosaic technique is also found at the Wazir Khan Mosque along with long panels of calligraphy in nastaliq, thuluth and naskh scripts.

There are staircases inside the minaret to reach at the top to have a view of the city. But access to these minarets is usually not allowed. A number of rooms are lined up on both sides of the main prayer hall. Most of these rooms remain closed and the rest are rented out to various types of vendors and calligraphers.

After visiting the mosque in 2004, US Embassy officials had allocated a fund of $31,000 under the US Ambassador’s Fund for Cultural Preservation programme for the restoration of the mosque. They showed their concerns about the fast decay of the mosque. Most parts of the mosque were restored to their original form. But still an operation against encroachments, neighbouring shops and houses is needed to preserve the splendour of the mosque.