Tamil Nadu: Assembly elections

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History

1962-2016

Vote share in Tamil Nadu assembly elections, 1962-2016

From: May 3, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

Seats won by parties in Tamil Nadu assembly elections;

Vote share in Tamil Nadu assembly elections, 1962-2016

1980, 2006, 2011 Assembly elections

From: Jaya Menon March 20, 2021: The Times of India

From: Jaya Menon March 20, 2021: The Times of India

From: Jaya Menon March 20, 2021: The Times of India

See graphics:

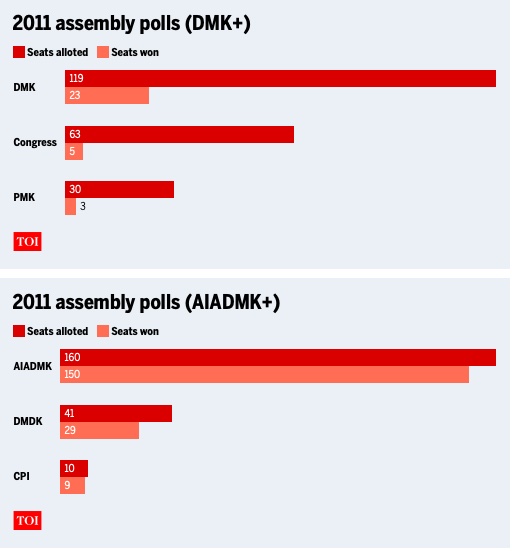

1980 Tamil Nadu assembly polls (DMK+ and AIDMK+)

2006 Tamil Nadu assembly polls (DMK+ and AIDMK+)

2011 Tamil Nadu assembly polls (DMK+ and AIDMK+)

Manifestoes: Their importance in TN

The Times of India, Apr 13 2016

Arun Ram When M Karunanidhi released the DMK manifesto for the 2011 assembly elections, many thought it was his masterstroke. Having delivered on his 2006 promise of free colour TV sets, this time the DMK sought to move from the voter's drawing room to the kitchen with the promise of free mixies or grinders -whichever the woman of the house chose.

Also up for grabs were free laptops for SCST students and 35kg of free rice for families below the poverty line.

Three days later, AIADMK supremo J Jayalalithaa beat Karunanidhi at his game: Why choose between a mixie and a grinder, she told voters, take both. As Karunanidhi sweated over a counter strategy , Amma offered each household a fan too.

What followed was a tit-for-tat, as the electorate watched with glee. But with Jayalalithaa unbundling her sop bag overflowing with free rice, laptops for all senior students and gold for women, there were no prizes for guessing the winner. And with the AIADMK government delivering the doles, even adding goats to the goodies, the manifesto was redefined as a popular document.

So, today, the making of the manifesto is serious business in political war rooms. Parties constitute panels with senior members and external ex perts, including economists, to brainstorm; the media and voters wait curiously for the highlights. DMK's this time is a two-part manifesto, with glossy pages and multi-colour text under heads of sec tors and districts. While the party's proposals on education, health and welfare have mostly been glossed over, the mention of free smartphones has got the eyeballs.

IIT economics professor M Suresh Babu sees the newfound importance of mani festos as a sign of sopdriven, competitive politics. “Parties have realised that promises matter more than vision, especially with on, especially with the middle-class, to bring about an elec toral swing. Earlier, party cadres deliv ered on promises and report cards, now manifestos do it,“ says Babu.

In the process, he notes, the relevance of welfare has been hijacked by freebies. “It's unfortunate that a large part of the public discussions on manifestos are about freebies.“ And here is the danger of mistaking freebies for welfare measures, and proposals with long-lasting welfare potential not being debated.

Observer and retired Madras HC judge K Chandru doesn't think people take manifestos seriously , but agrees freebies have an impact, sometimes unexpected.“DMK gained from promising TV sets in 2006, but later analysts concluded that it lost the 2011 polls as the same TV sets beamed programmes showing the negatives of the government,“ he says.

But do freebies amount to bribing voters? Chandru draws attention to a petition by Subramaniya Balaji, an advocate who sought a ban on freebies in manifestos as they amounted to illegal gratification.

The Supreme Court bench headed by then Chief Justice P Sathasivam rejected the petition and held that they are similar to the directive principles of state policy found under Part IV of the Constitution. It extracted the election manifesto of AIADMK (2009).

The court held that the Election Commission should take a call. Though the poll panel issued notice to parties, nothing came of it.

Implementing the DMK's 2016 manifesto would cost TN an additional Rs70,000 crore, 70% of the state's revenue. If you think that is impossible, wait for Amma's manifesto.

2016, assembly elections

From: Jaya Menon March 20, 2021: The Times of India

See graphic:

2016 Tamil Nadu assembly polls (DMK+ and AIDMK+)

Chennai votes DMK

The Times of India, May 20 2016

DMK could not capture Fort St George this time, but it has reclaimed one of its oldest bastions by winning 10 of the 16 Chennai seats, after a gap of 10 years.

While urban aspirations, that looked down upon CM Jayalalithaa's freebies, probably synchronised more with DMK's manifesto, the party's field work among flood-affected residents who were angry with the authorities propelled its performance this time.

Beyond the numbers, Chennai city constituencies have remained a matter of political prestige for the Dravidian giants. DMK was founded there in 1949. It remained the party's citadel till 2006 when the Jayalalithaa-led AIADMK won nine of the 14 constituencies. The number of city constituencies went up to 16 after delimitation prior to the 2011 elections, and AIADMK bettered its performance, winning 12 seats.

Bagging 10 seats this time marks a comeback for DMK which has done better overall across the state, compared to 2011 when it garnered only 23 seats in the assembly .

Chennai has been grappling with its transport and civic deficiencies. This must have cost AIADMK's candidates, including a couple of ministers in the outgoing cabinet, their seat.

“Bad roads, poor drainage and lack of proper public transport made people vote for DMK,“ said analyst Ravindran Doraisamy . “AIADMK MLAs and corporation councillors brought a bad name for the party .“ So voters reminded the Jayalalithaa government that it has to deliver more to keep the growing city happy .

2017

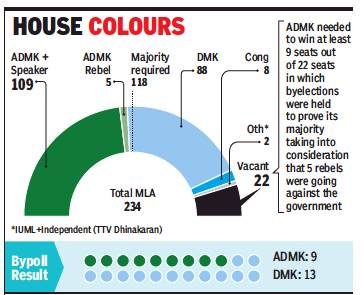

See graphic

Political crisis in Tamil Nadu to choose the Chief Minister in February 2017

2019 by elections: ADMK wins 9/22

May 24, 2019: The Times of India

From: May 24, 2019: The Times of India

With 9 seats in bag, EPS wards off threat to Tamil Nadu govt, for now

Chennai:

Tamil Nadu CM Edappadi K Palaniswami has withstood yet another acid test with AIADMK winning the required nine out of the 22 assembly seats where bypolls were held. There is no major threat to his government now. The ruling party has 117 MLAs — excluding the speaker and five rebels — in the 234-member House.

In the light of the threat posed by the rebels and the no-confidence motion proposed against the speaker, the ruling party needed to win nine seats and the party has just about managed it.

For now, the chief minister would not be unduly worried about the revolt of five AIADMK rebels. “EPS and OPS have proven beyond doubt that they represent the real AIADMK. With TTV Dhinakaran’s AMMK faring poorly in the bypolls, new desertions and activation of the so-called sleeper cells he has been talking about are unlikely to happen,” said analyst M Kasinathan.

The nine newly-elected MLAs being Edappadi’s choice, they are unlikely to switch camps. Moreover, since the elections have exhausted all the AIADMK leaders, they are not psychologically and financially ready to face yet another election. DMK president M K Stalin, perhaps, failed to understand Edappadi’s game plan. Focused on cobbling together a government headed by Rahul Gandhi at the Centre, Stalin lost focus on his immediate task in hand. In the process, he has lost yet another opportunity to pull down the shaky AIADMK government in Tamil Nadu.

Power has virtually slipped through Stalin’s fingers. Crafty Palaniswami, knowing well it was an arduous task to garner votes in Tamil Nadu to prop up a Modi government at the Centre, set his focus right from the beginning on winning as many assembly seats as possible in the byelections to safeguard his chair.

Even the grand alliance for the LS polls was formed keeping the assembly bypolls in mind. He put considerable amount of resources to work in the 22 assembly seats to put the brakes on the DMK juggernaut. Despite Dhinakaran eating into the thevar vote base of AIADMK and DMK walking away with the minority votes, Palaniswami remained focused, believing in his strengths and doing things he is good at.

The AIADMK government had looked precarious ever since Jayalalithaa’s demise in December 2016. Coming together for power and to keep their common enemy Dhinakaran at bay, Edappadi and his deputy O Panneerselvam have steered the government through turbulent waters for two years. The byelections were forced on the ruling party by Dhinakaran, who engineered defection of 18 AIADMK MLAs. The next assembly elections are two years away, which is very long a period in politics. The opposition parties may not get such a conducive opportunity once again to pull down the government. Palaniswami has enough time to graduate from chief minister of Salem to chief minister of Tamil Nadu.

Captain’s 15 years of hard work comes to nought, fails to open account

It took 15 years for actor Vijayakant to establish his political career. All the hard work came to nought on Thursday when his DMDK, which bargained with both Dravidian majors before accepting the four Lok Sabha seats offered by AIADMK, drew a blank. DMDK made an impressive debut in the 2006 Assembly election, pitted against J Jayalalithaa’s AIADMK and M Karunanidhi-led DMK. It polled a credible 27 lakh votes and a vote share of more than 8% vote share despite just Vijayakant’s win in Vriddhachalam.

The deaths of Jayalalithaa and Karunanidhi changed things and in 2019 election, a desperate BJP and AIADMK brought DMDK back into the limelight. But the way his family members arrogantly bargained with the two major fronts, as a visibly-ill Vijayakant remained in the background in front of the camera, left an indelible mark at the campaign stage itself, hastening the end. The Captian can now only sulk in silence. TEAM TOI

2021

DMK wins

May 3, 2021: The Times of India

From: May 3, 2021: The Times of India

Stalin-grad: The Son Rises After 10 Years

Urban Wave Makes Up For Rural Deficit

The DMK alliance’s victory by a margin of roughly 80 seats wasn’t a surprise to many including discerning observers in the AIADMK. Edappadi K Palaniswami’s ratings as a chief minister were high, but his image makeover from that of an accidental CM four years ago to a survivor a year later to a performer in the past year was just not enough to retain power given AIADMK’s uninterrupted run for 10 years.

The TN result shows antiincumbency in the state is not always a roaring wave, it could be a silent undercurrent. AIADMK’s apparent deference to BJP added swirls to the current while DMK president M K Stalin rode expectations that outweighed allegations of dynasty politics.

Both sides broadly played to their strengths. DMK’s tally was boosted by its performance in urban segments where it won 40 of its 156 seats while AIADMK had a better score in the rural parts, which elected 61 of its 78 MLAs. In seats with a minority electorate of over 20%, AIADMK surprisingly did not concede much ground despite the BJP being its alliance partner. It won 7 out of 27 such constituencies while the rest went to the DMK.

EPS government’s poll-eve order allocating a 10.5% subquota within the most backward caste category to vanniyars—apparently to keep the PMK on its side—seems to have resulted in a backlash from AIADMK’s thevar base in southern TN. The western region where gounders (the community the CM belongs to) are predominant still gave it its biggest chunk of seats.

All in all, the DMK alliance’s efforts to paint AIADMK as one taking orders from the ‘outsider’ BJP paid dividends. On the other hand, AIADMK’s charges of the DMK being a family-controlled party did not matter, what with Stalin’s son Udhayanidhi winning his electoral debut from Thousand Lights in Chennai with a record margin.

AIADMK, which forged an uneasy peace among factions following J Jayalalithaa’s death in December 2016, will now face another challenge if her former aide V K Sasikala tries to fish in troubled waters.

For Modi-Shah, the result is a double blow. Besides the failure to get a strong foothold in the heart of the South, it is also the loss of a friendly, even pliable, state government. AIADMK MPs, who were in good numbers in both houses before 2019, have been a supportive bunch, backing crucial bills such as CAA and farm laws notwithstanding the protests some of them registered in Parliament to play to their home audiences.

Congress has fared somewhat better, winning 18 seats in DMK’s company. Having contested 25 this time (a climbdown from 41 in 2016), the party remains a minor ally. The 2021 assembly election results have thus cemented Tamil Nadu’s image as a Dravidian fort impregnable for national parties.

National parties

May 3, 2021: The Times of India

For more than 50 years, the Congress has been struggling to find ways to stem its decline in the Dravidian heartland and for over 40 years, BJP has been toiling to make inroads. Hitting roadblocks, both have reconciled to piggybacking on the Dravidian majors — DMK and AIADMK — to stay afloat. Finally, Congress is likely to win 18 seats and BJP 4. BJP’s last win was in the 2001 assembly polls, when it got 4 seats.

Southern districts have favoured Congress the most. Interestingly, except Congress chief whip in assembly, S Vijayadharani, none of the winning candidates are heavyweights. In Karaikudi, the Congress candidate was set to win thanks to P Chidambaram’s influence in the region. In more than a dozen seats, Congress is dependent on DMK’s strength .

The BJP was set to win one seat each in Kanyakumari and Coimbatore districts, its strongholds. Actor Kamal Haasan lost to BJP’s Vanathi Srinivasan. Ex-transport minister Nainar Nagendran who left AIADMK and joined BJP 3 years ago, was set to win from Tirunelveli.

Voice of Tamil Eelam 3rd in many seats

D Govardan , May 3, 2021: The Times of India

After this assembly election, Seeman’s will be the voice of the opposition,” poll strategist Prashant Kishor had told TOI in the midst of the campaign. Starting off as an extremist with vocal support to LTTE’s Prabhakaran and the cause of the Tamil Eelam (homeland), the former film director has created his own space in Tamil Nadu’s mainstream politics.

Seeman’s Naam Thamizhar Katchi (NTK) hasn’t won a single seat, but it has come third in many. Of the 234 candidates his party fielded, 117 are women.

Through his rabble-rousing speeches, Seeman has built a strong following among educated youth. He has also penetrated micro-communities, which did not have much say in the Dravidian parties. MDMK chief M Vaiko, a vocal supporter of Tamil Eelam, is now part of the DMK front.

“DMK is our political enemy and BJP our ideological enemy,” Seeman had told TOI some time ago. “Congress is the enemy of the Tamil community, while BJP is the enemy of mankind itself,” has been his rhetoric of late.