Himalayas

Contents[hide] |

An overview

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.

The system of stupendous mountain ranges, lying

along the northern frontiers of the Indian Empire, and containing some

of the highest peaks in the world. Literally, the name is equivalent

to ' the abode of snow ' (from the Sanskrit hima, ' frost,' and alaya,

'dwelling-place'). To the early geographers the mountains were

known as Imaus or Himaus and Hemodas ; and there is reason to

believe that these names were applied to the western and eastern parts

respectively, the sources of the Ganges being taken as the dividing line.

' Hemodas ' represents the Sanskrit Himavata (Prakrit He/iiota), mean-

ing 'snowy.' The Greeks who accompanied Alexander styled the

mountains the Indian Caucasus.

Modern writers have sometimes included in the system the Muztagh range, and its extension the Karakoram ; but it is now generally agreed that the Indus should be considered the north-western limit. From the great peak of Nanga Parbat in Kashmir, the Himalayas stretch eastward for twenty degrees of longitude, in a curve which has been compared to the blade of a scimitar, the edge facing the plains of India. Barely one-third of this vast range of mountains is known with any degree of accuracy. The Indian Survey department is primarily engaged in supplying administrative needs ; and although every effort is made in fulfilling this duty to collect information of purely scientific interest, much still remains to be done.

A brief abstract of our knowledge of the Himalayas may be given by shortly describing the political divisions of India which include them. On the extreme north-west, more than half of the State of KashmIr .AND Jammu lies in the Himalayas, and this portion has been described in some detail by Drew in Jammu and Kashmir Territories^ and by Sir W. Lawrence in The Valley of Kashmir. The next section, appertaining to the Punjab and forming the British District of Kangra and the group of feudatories known as the Simla Hill States, is better known. East of this lies the Kumaun Division of the United Provinces, attached to which is the Tehrl State. This portion has been surveyed in detail, owing to the requirements of the revenue administration, and is also familiar from the careful accounts of travellers.

For 500 miles the State of Nepal occupies the mountains, and is to the present day almost a terra incognita, owing to the acquiescence by the British Government in the policy of exclusion adopted by its rulers. Our knowledge of the topography of this portion of the Himalayas is limited to the information obtained during the operations of 18 16, materials collected by British ofificials resident at Katmandu, notably B. H. Hodgson, and the accounts of native explorers. The eastern border of Nepal is formed by the State of Sikkim and the Bengal District of Darjeeling, which have been graphically described by Sir Joseph Hooker and more recently by Mr. Douglas Freshfield. A small wedge of Tibetan territory, known as the Chumbi Valley, separates Sikkim from Bhutan, which latter has seldom been visited by Euro- peans. East of Bhutan the Himalayas are inhabited by savage tribes, Avith whom no intercourse is possible except in the shape of punitive expeditions following raids on the plains. Thus a stretch of nearly 400 miles in the eastern portion of the range is imperfectly known.

In the western part of the Himalayas, which, as has been shown, has been more completely examined than elsewhere, the system may be divided into three portions. The central or main axis is the highest, which, starting at Nanga Parbat on the north-west, follows the general direction of the range. Though it contains numerous lofty peaks, including Nanda Devi, the highest mountain in British India, it is not a true watershed. North of it lies another range, here forming the boundary between India and Tibet, which shuts off the valley of the Indus, and thus may be described as a real water-parting. From the central axis, and usually from the peaks in it, spurs diverge, with a general south-easterly or south-westerly direction, but actually winding to a considerable extent. These spurs, which may be called the Outer Himalayas, cease with some abruptness at their southern extremities, so that the general elevation is 8,000 or 9,000 feet a few miles from the plains. Separated from the Outer Himalayas by elevated valleys or duns is a lower range known as the Siwaliks, which is well marked between the Beas and the Ganges, reappears to the south of central Kumaun, and is believed to exist in Nepal. Although the general character of the Himalayas in Nepal is less accurately known, there is reason to suppose that it approximates to that of the western ranges.

Within the limits of this great mountain chain all varieties of scenery can be obtained, except the placid charm of level country. Luxuriant vegetation clothes the outer slopes, gradually giving place to more sombre forests. As higher elevations are reached, the very desolation of the landscape affects the imagination even more than the beautiful scenery left behind. It is not surprising that these massive peaks are venerated by the Hindus, and are intimately connected with their religion, as giving rise to some of the most sacred rivers, as well as on account of legendary associations. A recent writer has vividly described the impressions of a traveller through the foreground of a journey to the snows in Sikkim ' : —

' D. W. Freshfield in The Geographical Journal, vol. xix, p. 453. He sees at one glance the shadowy valleys from which shhiing mist-columns rise at noon against a luminous sky, the forest ridges, stretching fold behind fold in softly undulating lines — dotted by the white specks which mark the situation of Buddhist monasteries — to the glacier-draped pinnacles and precipices of the snowy range. He passes from the zone of tree-ferns, bamboos, orange-groves, and dal forest, through an endless colonnade of tall-stemmed magnolias, oaks, and chestnut trees, fringed with delicate orchids and festooned by long convolvuluses, to the region of gigantic pines, junipers, firs, and larches. Down each ravine sparkles a brimming torrent, making the ferns and flowers nod as it dashes past them. Superb butterflies, black and blue, or flashes of rainbow colours that turn at pleasure into exact imitations of dead leaves, the fairies of this lavish transformation scene of Nature, sail in and out between the sunlight and the gloom. The mountaineer pushes on by a track half buried between the red twisted stems of tree-rhododendrons, hung with long waving lichens, till he emerges at last on open sky and the upper pastures — the Alps of the Himalaya — fields of flowers : of gentians and edelweiss and poppies, which blossom beneath the shining storehouses of snow that encompass the ice-mailed and fluted shoulders of the giants of the range. If there are mountains in the world which combine as many beauties as the Sikkim Himalayas, no traveller has as yet discovered and described them for us.'

The line of perpetual snow varies from 15,000 to 16,000 feet on the southern exposures. In winter, snow generally falls at elevations above 5,000 feet in the west, while falls at 2,500 feet were twice recorded in Kumaun during the last century. Glaciers extend below the region of perpetual snow, descending to 12,000 or 13,000 feet in Kulu and Lahul, and even lower in Kumaun, while in Sikkim they are about 2,000 feet higher. On the vast store-house thus formed largely depends the prosperity of Northern India, for the great rivers which derive their water from the Himalayas have a perpetual supply which may diminish in years of drought, but cannot fail absolutely to feed the system of canals drawn from them.

While all five rivers from which the Punjab derives its name rise in the Himalayas, the Sutlej alone has its source beyond the northern range, near the head-waters of the Indus and Tsan-po. In the next section are found the sources of the Jumna, Ganges, and Kali or Sarda high up in the central snowy range, while the Kauriala or Karnali, known lower down in its course as the Gogra, rises in Tibet, beyond the northern watershed. The chief rivers of Nepal, the Gandak and Kosi, each with seven main affluents, have their birth in the Himalayas, which here supply a number of smaller streams merging in the larger rivers soon after they reach the plains. Little is known of the upper courses of the northern tributaries of the Brahma[)utra in Assam ; but it seems probable that the Dihang, which has been taken as the eastern boundary of the Himalayas, is the channel connecting the Tsan-po and the Brahmaputra.

Passing from east to west the principal peaks are Nanga Parbat (26,182 feet) in Kashmir; a peak in Spiti (Kangra District) exceed- ing 23,000, besides three over 20,000; Nanda Devi (25,661), Trisul (23,382), Panch Chulhi (22,673), ^"^J Nanda Kot (22,538) in the United Provinces ; Mount Everest (29,002), Devalagiri (26,826), Gosainthan (26,305) and Kinchinjunga (28,146), with several smaller peaks, in Nepal; and Dongkya (23,190), with a few rising above 20,000, in Sikkim.

The most considerable stretch of level ground is the beautiful Kashmir Valley, through which flows the Jhelum. In length about 84 miles, it has a breadth varying from 20 to 25 miles. Elsewhere steep ridges and comparatively narrow gorges are the rule, the chief exception being the Valley of Nepal, which is an undulating plain about 20 miles from north to south, and 12 to 14 miles in width. Near the city of Srinagar is the Dal Lake, described as one of the most picturesque in the world. Though measuring only 4 miles by 2^, its situation among the mountains, and the natural beauty of its banks, combined with the endeavours of the Mughal emperors to embellish it, unite to form a scene of great attractions. Some miles away is the larger expanse of water known as the Wular Lake, which ordinarily covers \2\ square miles, but in years of flood expands to over 100. A number of smaller lakes, some of considerable beauty, are situated in the outer ranges in Naini Tal District. \\\ 1903 the Gohna Lake, in Garhwal District, was formed by the subsidence of a steep hill, rising 4,000 feet above the level of a stream which it blocked.

The geological features of the Himalayas can be conveniently grouped into three classes, roughly corresponding to the three main orographical zones : (i) the Tibetan highland zone, (2) the zone of snowy peaks and Outer Himalayas, and (3) the Sub-Himalayas.

In the Tibetan highlands there is a fine display of marine fossiliferous rocks, ranging in age from Lower Palaeozoic to Tertiary. In the zone of the snowy peaks granites and crj-stalline schists are displayed, fringed by a mantle of unfossiliferous rocks of old, but generally unknown, age, forming the lower hills or Outer Himalayas, while in the Sub-Himalayas the rocks are practically all of Tertiary age, and are derived from the waste of the highlands to the north.

The disposition of these rocks indicates the existence of a range of some sort since lower palaeozoic times, and shows that the present southern boundary of the marine strata on the northern side of the crystalline axis is not far from the original shore of the ocean in which these strata were laid down. The older unfossiliferous rocks of the By T. H, Holland, Geological Survey of India. Lower Himalayas on the southern side of the main crystalline axis are more nearly in agreement with the rocks which ha\e been preserved without disturbance in the Indian Peninsula; and even remains of the great Gondwana river-formations which include our valuable deposits of coal are found in the Darjeeling area, involved in the folding move- ments which in later geological times raised the Himalayas to be the greatest among the mountain ranges of the world. The Himalayas were thus marked out in very early times, but the main folding took place in the Tertiary era. The great outflow of the Deccan trap was followed by a depression of the area to the north and west, the sea in eocene times spreading itself over Rajputana and the Indus valley, covering the Punjab to the foot of the Outer Himalayas as far east as the Ganges, at the same time invading on the east the area now- occupied by Assam. Then followed a rise of the land and consequent retreat of the sea, the fresh-water deposits which covered the eocene marine strata being involved in the movement as fast as they were formed, until the Sub-Himalayan zone river-deposits, no older than the pliocene, became tilted up and even overturned in the great foldings of the strata. This final rise of the Himalayan range in late Tertiary times was accompanied by the movements which gave rise to the Arakan Yoma and the Naga Hills on the east, and the hills of Baluchistan and Afghanistan on the west.

The rise of the Himalayan range may be regarded as a great buckle in the earth's crust, which raised the great Central Asian plateau in late Tertiary times, folding over in the Baikal region on the north against the solid mass of Siberia, and curling over as a great wave on the south against the firmly resisting mass of the Indian Peninsula.

As an index to the magnitude of this movement within the Tertiary era, we find the marine fossil foraniinifer, Nii>nmuiites, which lived in eocene times in the ocean, now at elevations of 20,000 feet above sea-level in Zaskar. With the rise of the Himalayan belt, there occurred a depression at its southern foot, into which the alluvial material brought down from the hills has been dropped by the rivers. In miocene times, when presumably the Himalayas did not possess their present elevation, the rivers deposited fine sands and clays in this area ; and as the elevatory process went on, these deposits became tilted up, while the rivers, attaining greater velocity with their increased gradient, brought down coarser material and formed conglomerates in pliocene times. These also became elevated and cut into by their own rivers, which are still working along their old courses, bringing down boulders to be deposited at the foot of the hills and carrying out the finer material farther over the Indo-Gangctic plain.

The series of rocks which have thus been formed by the rivers, and afterwards raised to form the Sub-Himalayas, are known as the Siwalik series. They are divisible into three stages. In the lowest and oldest, distinguished as the Nahan stage, the rocks are fine sandstones and red clays without any pebbles. In the middle stage, strings of pebbles are found with the sandstones, and these become more abundant towards the top, until we reach the conglomerates of the upper stage. Along the whole length of the Himalayas these Siwalik rocks are cut off from the older rock systems of the higher hills by a great reversed fault, which started in early Siwalik times and developed as the folding movements raised the mountains and involved in its rise the deposits formed along the foot of the range. The Siwalik strata never extended north of this great boundary fault, but the continued rise of the mountains affected these deposits, and raised them up to form the outermost zone of hills.

The upper stage of the Siwalik series is famous on account of the rich collection of fossil vertebrates which it contains. Among these there are forms related to the miocene mammals of Europe, some of which, like the hippopotamus, are now unknown in India but have relatives in Africa. Many of the mammals now characteristic of India were repre- sented by individuals of much greater size and variety of species in Siwalik times.

The unfossiliferous rocks which form the Outer Himalayas are of unknown age, and may possibly belong in part to the unfossiliferous rocks of the Peninsula, like the Vindhyans and the Cuddapahs. Conspicuous among these rocks are the dolomitic limestones of Jaunsar and Kumaun, the probable equivalents of the similar rocks far away to the east at Buxa in the Duars. With these a series of purple quartzites and basic lava-flow is often associated. In the Simla area the un- fossiliferous rocks have been traced out with considerable detail ; and it has been shown that quartzites, like those of Jaunsar and Kumaun, are overlaid by a system of rocks which has been referred to the carbonaceous system on account of the black carbonaceous slates which it includes. The only example known of pre-Tertiary fossiliferous rocks south of the snowy range in the Himalayas occurs in south-west Garhwal, where there are a few fragmentary remains of mesozoic fossils of marine origin.

The granite rocks, which form the core of the snowy range and in places occur also in the Lower Himalayas, are igneous rocks which may have been intruded at different periods in the history of the range. They are fringed with crystalline schists, in which a progressive metamorphism is shown from the edge of granitic rock outwards, and in the inner zone the granitic material and the pre-existing sedimentary rock have become so intimately mixed that a typical banded gneiss is produced. The resemblance of these gneisses to the well-known gneisses of Archaean age in the Peninsula and in other parts of the world led earlier observers to suppose that the gneissose rocks of the Central Himalayas formed an Archaean core, against which the sediments were subsequently laid down. But as we now know for certain that both granites, such as we have in the Himalayas, and banded gneisses may be much ycjunger, even Tertiary in age, the mere composition and structure give no clue to the age of the crystalline axis. The position of the granite rock is probably dependent on the development of low-pressure areas during the process of folding, and there is thus a prima facie reason for supposing that much of the igneous material became injected during the Tertiary period. With the younger intrusions, however, there are probably remains of injections which occurred during the more ancient movements, and there may even be traces of the very ancient Archaean gneisses ; for we know that pebbles of gneisses occur in the Cambrian conglomerates of the Tibetan zone, and these imply the existence of gneissose rocks exposed to the atmosphere in neighbouring highlands. The gneissose granite of the Central Himalayas must have consolidated under great pressure, with a thick superincumbent envelope of sedimentary strata ; and their exposure to the atmosphere thus implies a long period of effectual erosion by weathering agents, which have cut down the softer sediments more easily and left the more resisting masses of crystalline rocks to form the highest peaks in the range. Excellent illustrations of the relationship of the gneissose granites to the rocks into which they have been intruded are displayed in the Dhaola Dhar in Kulu, in the Chor Peak in Garhwal, and in the Darjeeling region east of Nepal.

Beyond the snowy range in the Tibetan zone we have a remarkable display of fossiliferous rocks, which alone would have been enough to make the Himalayas famous in the geological world. The boundary between Tibetan territory and Spiti and Kumaun has been the area most exhaustively studied by the Geological Survey. The rocks exposed in this zone include deposits which range in age from Cambrian to Tertiary. The oldest fo.ssiliferous system, distinguished as the Haimanta ('snow-covered') system, includes some 3,000 feet of the usual sedi- mentary types, with fragmentary fossils which indicate Cambrian and Silurian affinities. Above this system there are representatives of the Devonian and Carboniferous of Europe, followed by a conglomerate which marks a great stratigraphical break at the beginning of Permian times in Northern India. Above the conglomerate comes one ol the most remarkably complete succession of sediments known, ranging from Permian, without a sign of disturbance in the process of sedimentation, throughout The whole Mesozoic epoch to the beginning of Tertiary times. The highly fossiliferous character of some of the formations in this great pile of strata, like the Proditdus shales and the Spiti shales, has made this area classic ground to the palaeontologist.

vol.. XIII. K The Eurasian ocean distinguished by the name 'Thetys,' which spread over this area throughout the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic times, became driven back by the physical revolution which began early in Tertiary times, when the folding movements gave rise to the modern Himalayas. As relics of this ocean have been discovered in Burma and China it will not be surprising to find, when the ground has been more thoroughly explored, that highly fossiliferous rocks are preserved also in the Tibetan zone beyond the snowy ranges of Nepal and Sikkim.

Of the minerals of value, graphite has been recorded in the Kumaun Division ; coal occurs frequently amongst the Nummulitic (eocene) rocks of the foot-hills and the Gondwana strata of Darjeeling District ; bitumen has been found in small quantities in Kumaun ; stibnite, a sulphide of antimony, occurs associated with ores of zinc and lead in well-defined lodes in Lahul ; gold is obtained in most of the rivers, and affords a small and precarious living for a few washers ; copper occurs very widely disseminated and sometimes forms distinct lodes of value in the slaty series south of the snowy range, as in the Kulu, Kumaun, and Darjeeling areas ; ferruginous schists sometimes rich in iron occur under similar geological conditions, as in Kangra and Kumaun ; sapphires of considerable value have been obtained in Zaskar and turquoise from the central highlands ; salt is being mined in quantity from near the boundary of the Tertiary and older rocks in the State of Mandi ; borax and salt are obtained from lakes beyond the Tibetan border ; slate-quarrying is a flourishing industry along the southern slopes of the Dhaola Dhar in Kangra District ; mica of poor quality is extracted from the pegmatites of Kulu ; and a few other minerals of little value, besides building stones, are obtained in various places. A small trade is developed, too, by selling the fossils from the Spiti shales as sacred objects.

The general features of the great variety in vegetation have been illustrated in the quotation from Mr. Freshfield's description of Sikkim. These variations are naturally due to an increase in elevation, and to the decrease in rainfall and humidity passing from south to north, and from east to west. The tropical zone of dense forest extends up to about 6,500 feet in the east, and 5,000 feet in the west. In the Eastern Himalayas orchids are numerically the predominant order of flowering plants ; while in Kumaun about 62 species, both epiphytic and terrestrial, have been found. A temperate zone succeeds, ranging to about 12,000 feet, in which oaks, pines, and tree-rhododendrons are conspicuous, with chestnut, maple, magnolia, and laurel in the east. Where rain and mist are not excessive, as for example in Kulu and Kumaun, European fruit trees (apples, pears, apricots, and peaches) have been naturalized very successfully, and an important crop of potatoes is obtained in the west. Above about 12,000 feet the forests become thinner. Birch and willow mixed with dwarf rhododendrons continue for a time, till the open pasture land is reached, which is richly adorned in the summer months with brilliant Alpine species of flowers. Contrasting the western with the eastern section we find that the former is far less rich, though it has been better explored, while there is a preponderance of European species. A fuller account of the botanical features of the Himalayas will be found in Vol. I, chap. iv.

To obtain a general idea of the fauna of the Himalayas it is sufificient to consider the whole system as divided into two tracts : namely, the area in the lower hills where forests can flourish, and the area above the forests. The main characteristics of these tracts have been summarized by the late Dr. W. T. Blanford^ In the forest area the fauna differs markedly from that of the Indian Peninsula stretching away from the base of the hills. It does not contain the so-called Aryan element of mammals, birds, and reptiles which are related to Ethiopian and Holarctic genera, and to the pliocene Siwalik fauna, nor does it include the Dravidian element of reptiles and batrachians. On the other hand, it includes the following animals which do not occur in the Peninsula — Mammals : the families Simiidae, Procyonidae, Talpidae, and Spalacidae, and the sub-family Gymnurinae, besides numerous genera, such as Frionodon, Helictis, Anfonyx, Athe- rura, IVemorhaedus, and Cemas. Birds : the families Eurylaemidae, Indicatoridae, and Heliornithidae, and the sub-family Paradoxornithinae. Reptiles : Platysternidae and Anguidae. Batrachians : Dyscophidae, Hylidae, Pelobatidae, and Salamandridae. Compared with the Penin- sula, the fauna of the forest area is poor in reptiles and batrachians.

' It also contains but few peculiar genera of mammals and birds, and almost all the peculiar types that do occur have Holarctic affinities. The Oriental element in the fauna is very richly represented in the Eastern Himalayas and gradually diminishes to the westward, until in Kashmir and farther west it ceases to be the principal constituent. These facts are consistent with the theory that the Oriental constituent of the Himalayan fauna, or the greater portion of it, has migrated into the mountains from the eastward at a comparatively recent period. It is an important fact that this migration appears to have been from Assam and not from the Peninsula of India.'

Dr. Blanford suggested that the explanation was to be found in the conditions of the glacial epoch. When the spread of snow and ice took place, the tropical fauna, which may at that time have resembled more closely that of the Peninsula, was forced to retreat to the base of the mountains or perished. At such a time the refuge afforded by the Assam Valley and the hill ranges south of it, with their damp,

' 'The Distribution of Vcrtcl)rale Animals in India, Ceylon, and IJurnia,' Pio- cecdtngs, Royal Socrc/y, vol. Ixvii, p. 484. sheltered, forest-clud valleys, would be more secure than the open plains of Northern India and the drier hills of the country south of these. As the cold epoch passed away, the Oriental fauna re-entered the Himalayas from the east.

Above the forests the Himalayas belong to the Tibetan sub-region of the Holarctic region, and the fauna differs from that of the Indo- Malay region, 44 per cent, of the genera recorded from the Tibetan tract not being found in the Indo-Malay region. During the glacial epoch the Holarctic forms apparently survived in great numbers.

Owing to the rugged nature of the country, which makes travelling difficult and does not invite immigrants, the inhabitants of the Himalayas present a variety of ethnical types which can hardly be summarized briefly. Two common features extending over a large area may be referred to. From Ladakh in Kashmir to Bhutan are found races of Indo-Chinese type, speaking dialects akin to Tibetan and professing Buddhism. In the west these features are confined to the higher ranges ; but in Sikkim, Darjeeling, and Bhutan they are found much nearer the plains of India. Excluding Burma, this tract of the Himalayas is the only portion of India in which Buddhism is a living religion. As in Tibet, it is largely tinged by the older animistic beliefs of the people. Although the Muhammadans made various determined efforts to conquer the hills, they were generally unsuccessful, yielding rather to the difficulties of transport and climate than to the forces brought against them by the scanty though brave population of the hills. In the twelfth century a Tartar horde invaded Kashmir, but succumbed to the rigours of the snowy passes. Sub- sequently a Tibetan soldier of fortune seized the supreme power and embraced Islam. Late in the fourteenth century the Muhammadan ruler of the country. Sultan Sikandar, pressed his religion by force on the people, and in the province of Kashmir proper 94 per cent, of the total are now Muhammadans.

Baltistan is also inhabited chiefly by Muhammadans, but the proportion is much less in Jammu, and beyond the Kashmir State Islam has few followers. Hinduism becomes an important religion in Jammu, and is predominant in the southern portions of the Himalayas within the Punjab and the United Provinces. It is the religion of the ruling dynasty in Nepal, where, however, Buddhism is of almost equal strength. East of Nepal Hindus are few. Where Hinduism prevails, the language in common use, known as Paharl, presents a strong likeness to the languages of Rajputana, thus confirming the traditions of the higher classes that their ancestors migrated from the plains of India. In Nepal the languages spoken are more varied, and Newari, the ancient state language, is akin to Tibetan. The Mongolian element in the population is strongly marked in the east, but towards the west has been pushed back into the higher portion of the ranges. In Kumaun arc found a few shy people living in the recesses of the jungles, and having little intercourse with their more civilized neighbours. Tribes which appear to be akin to these are found in Nepal, but little is known about them. North of Assam the people are of Tibeto-Burman origin, and are styled, passing from west to east, the Akas, Daflas, Miris, and Abors, the last name signifying 'unknown savages.' Colonel Dalton has described these people in his Ethnology of Bengal.

From the commercial point of view the agricultural products of the Himalayas, with few exceptions, are of little importance. The chief food-grains cultivated are, in the outer ranges, rice, wheat, barley, mariid, and amaranth. In the hot, moist valleys, chillies, turmeric, and ginger are grown. At higher levels potatoes have become an important crop in Kumaun ; and, as already mentioned, in Kulu and Kumaun European fruits have been successfully naturalized^ including apples, pears, cherries, and strawberries. Two crops are obtained in the lower hills ; but cultivation is attended by enormous difficulties, owing to the necessity of terracing and clearing land of stones, while irrigation is practicable only by long channels winding along the hill- .sides from the nearest suitable stream or spring. As the snowy ranges are approached wheat and buckwheat, grown during the summer months, are the principal crops, and only one harvest in the year can be obtained. Tea gardens were successfully established in Kumaun during the first half of the nineteenth century, but the most important gardens are now situated in Kangra and Darjeeling. In the latter District cinchona is grown for the manufacture of quinine and cinchona febrifuge.

The most valuable forests are found in the Outer Himalayas, yielding a number of timber trees, among which may be mentioned sal, shtshajH {Dalbergia Sissoo), and tun {Cedrela toona). Higher u[) are found the deodar and various kinds of pine, which are also extracted wherever means of transport can be devised. In the Eastern Himalayas wild rubber is collected by the hill tribes already mentioned, and brought for sale to the Districts of the Assam Valley.

Communications within the hills are naturally difficult. Railways have hitherto been constructed only to three places in the outer hills : Jammu in the Kashmir State, Simla in the Punjab, and Darjeeling in Bengal. Owing to the steepness of the hill-sides and the instability of the strata composing them, these lines have been costly to build and maintain. A more ambitious project is now being carried out to connect the Kashmir valley with the plains, motive power being supplied by electricity to be generated by the Jhelum river. The principal road practicable for wheeled traffic is also in Kashmir, leading from Rawalpindi in the i)!ains ihrougli Murixc and liaraniula to Srinagar, Other cart-roads have been made connecting with the plains the hill stations of Dharmsala, Simla, Chakrata, Mussoorie, Dalhousie, Naini Tal, and Ranlkhet, In the interior the roads are merely bridle-paths. The great rivers flowing in deep gorges are crossed by suspension bridges made of the rudest materials.

The sides consist of canes and twisted fibres, and the footway may be a single bamboo laid on horizontal canes supported by ropes attached to the sides. These frail constructions, oscillating from side to side under the tread of the traveller, are crossed with perfect confidence by the natives, even when bearing heavy loads. On the more frequented paths, such as the pilgrim road from Hardwar up the valley of the Ganges to the holy shrines of Badrinath and Kedarnath, more sub- stantial bridges have been constructed by Government, and the roads are regularly repaired. Sheep and, in the higher tracts, yaks and crosses between the yak and ordinary cattle are used as beasts of burden. The trade with Tibet is carried over lofty passes, the difficulties of which have not yet been ameliorated by engineers. Among these the following may be mentioned : the Kangwa La (15,500 feet) on the Hindustan-Tibet road through Simla; the Mana (18,000), NitI (16,570), and Balcha Dhura in Garhwal ; the Anta Dhura (17,270), Lampiya Dhura (18,000), and Lipu Lekh (16,750) in Almora ; and the Jelep La (14,390) in Sikkim.

[More detailed information about the various portions of the Himalayas will be found in the articles on the political divisions referred to above. An admirable summary of the orography of the Himalayas is contained in Lieut.-Col. H. H. Godwin-Austen's presidential address to the Geographical Section of the British Association in 1883 {Froceedi?igs, Royal Geographical Society, 1883, p. 610; and 1884, pp. 83 and 112, with a map). Fuller accounts of the botany, geology, and fauna are given in E. F. Atkinson's Gazetteer of the Himdlayati Districts in the North- Western [United] Provinces, 3 vols. (1882-6). See also General Strachey's 'Narrative of a Journey to Manasarowar,' Geographical Journal, vol. xv, p. 150. More recent works are the Kdngra District Gazetteer (Lahore, 1899);

C. A. Sherring, Western Tibet atid the British Borderland (1906) ; and

D. W. Freshfield, Round Kangchetijimga (1903), which contains a full bibliography for the Eastern Himalayas. An account of The Himalayas by officers of the Survey of India and the Geological department is under preparation.]

Contribution to ecology, economy

‘An aerosol factory’

Chandrima Banerjee, December 28, 2020: The Times of India

Aerosols are not entirely well understood. Most cool the planet, some have a warming effect. Some make clouds last longer, others make them disappear. Just about 10% are human-generated and the rest, naturally occurring, are barely understood. But scientists have now found that nearly every day for centuries now, winds blasting up from the forests on the foothills of the Everest, through the valleys to the sky-piercing summit, have been working up an “aerosol factory.”

A study by 29 scientists from Finland, Italy, Switzerland, the US, France, Estonia and China published in ‘Nature Geoscience’ last week recorded observations from the remote Nepal Climate Observatory Pyramid station at 5,079m above sea level, a few kilometres from the summit .

“The concept of the Himalaya aerosol factory is that you need processes to form particles — the trees, the mountains, the wind,” lead author Federico Bianchi from the University of Helsinki in Finland told TOI. So far, it had been assumed that there might be aerosols that high up but measurements have been extremely limited.

“Plants at the foothills of the Himalayas emit large quantities of gases. These are transported by the wind through the valley to high altitudes. These gases (while they are transported) react in the air with atmospheric oxidants and form tiny particles,” Bianchi said. The initial size of these particles is 1-2 nanometre. But, by the time they approach the summit, they reach the size of 50-100 nm and become seeds for clouds.

So, what impact do they have on climate change?

So far, the general scientific consensus is that the cooling effect of aerosols has been able to partially counter the warming effect of greenhouse gases since the late 19th century. Dr Bianchi added, “This new source of particles can now be used in climate models for better climate change predictions and modelling future scenario.”

Environment and ecology

Groundwater

Himalayas “subside/ move up” depending on groundwater levels

The mighty Himalayas “subside and move up” depending on the seasonal changes in groundwater, said a new study, flagged by science ministry. It noted this as a unique phenomena where mountains literally “dance” to the tune of our groundwater consumption in the region.

Simply put, sinking of Himalayan foothills and the Indo-Gangetic plain now cannot be attributed only to geological phenomena (tectonic activity associated with landmass movement or continental drift) but also to variations of water availability beneath the ground.

Researchers from Indian Institute of Geomagnetism (IIG), in their study published recently in the Journal of Geophysical Research, through the combined use of Global Positioning System(GPS) and Gravity Recovery And Climate Experiment (GRACE) data quantified the variations of hydrological mass. “Nobody till now has looked at the rising Himalayas from a hydrological standpoint,” said the department of science & technology (DST) of the ministry which funded the study, noting how IIG’s Ajish Saji and other scientists looked at this phenomenon through this innovative prism using satellite data.

The GRACE satellites, launched by the US in 2002, monitor changes in water and snow stores on the continents. The study, which analysed the data, finds that an unsustainable consumption of groundwater associated to irrigation and other anthropogenic uses influence the subsidence rate in the Indo-Gangetic plain and sub-Himalayas.

Pollution

2016/ Mediterranean black carbon might be polluting Himalayas

A recent study by the Dehradun-based Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG) has found that black carbon travelling from Mediterranean countries during the western disturbance (which brings winter rains to India) may be one of the contributing factors leading to the receding snowline in the Himalayas.

Black carbon is formed through the incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, biofuel etc. The study recorded data for 12 months from January to December 2016 at Gangotri Glacier Valley in Chirbasa at an altitude of 3600 meters above sea level. Scientists involved in the study found that black carbon concentration at the site was high even in winter months although the area did not have any marked human activity which could have contributed to the pollution.

“The high concentration of black carbon in January and February is not originating from local sources because the entire population in these areas migrates to the plains for the winter.” said PS Negi, senior scientist, WIHG, Dehradun.

He added that “western disturbance is an extratropical storm originating from the Mediterranean region that brings sudden winter rain to the northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent.” “The material present in the atmosphere also gets transported during the western disturbance and this is what is impacting the environment and ecology of Himalayas.” Studies had earlier found a co-relation between black carbon concentration and melting of glaciers.

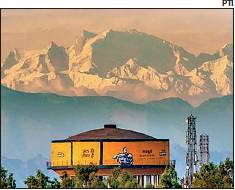

Sightings of Himalayan peaks

Hemali Chhapia, June 10, 2021: The Times of India

From: Hemali Chhapia, June 10, 2021: The Times of India

For centuries, the majestic Himalayas are believed to have yielded rare sightings of many mountain peaks from hundreds of kilometres away on a clear day. Now claims about such high visibility have been challenged by a student researcher and his mentor.

The lockdown was the most recent phase when a substantial drop in atmospheric particulate matter is believed to have cleared the way for a view of peaks normally obscured by pollution. But these claims of sightings of the Dhauladhar from Jalandhar and Mt Jomolhari in eastern Himalayas from Bhagalpur were questioned by the duo in a paper validated by a leading scientific journal.

Arnav Singh, a boy barely out of high school, and his mentor, Professor Vijay Singh, president of the Indian Association of Physics Teachers, revisited long-established reports of the sightings. Based on calculations of the distance and size of object and the intensity of light, they inferred that such sightings are unlikely to be true. The observer would have mistaken a larger or taller range for something else.

Arnav and his mentor found that, due to the earth’s curvature, the maximum distance one could see from the peak of Mt Jomolhari was 301km. “This was short of the distance of 366km between the peak and Bhagalpur,” said Singh, former faculty of IIT Kanpur. The finding was surprising since the 1785 observation of Jomolhari from Bhagalpur by Sir William Jones, known to be the greatest Orientalist of all times and founder of the Royal Society of Bengal, has been quoted often and recently in a famous book of John Keay’s called the ‘Great Arc’.

So which peak did Sir William Jones see? By analysing the observations of his successor to the Royal Society of Bengal, Henry Colebroke, Arnav and Singh surmised that in all probability it was Mt Kanchenjunga. As viewed from Bhagalpur, this mountain is in the same direction as Mt Jomolhari. It is also closer (297 km) and more visible and also taller (8,586km), debunking the claim.

The work by the duo was published last month by the American Journal of Physics. The referees and the American editor expressed delight while confirming acceptance of the collaborative research undertaken by a 17-yearold student and a 71-year-old professor.

See also

Himalayas