Droughts: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

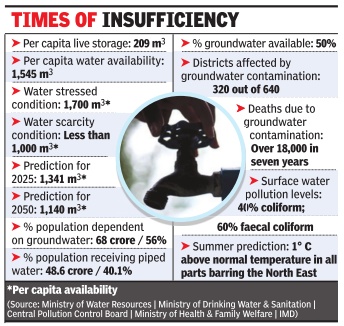

A water stressed country

The magnitude of the problem

Chethan Kumar, India can take just 1 more drought, Mar 25, 2017: The Times of India

Most Depend On Polluted Water Or Have No Access To Resource, Reveals Study

India is “water stressed“ and drifting inexorably towards what is technically termed a “water scarcity condition“. A majority of the country's populace is either forced to use contaminated water, or is deprived of access to the resource entirely .

As the country prepares for a harsh summer -the India Meteorological Department (IMD) forecasts temperatures will be 1°C above normal in most parts -the latest information from the Union water resources ministry reveals that India can sustain only one drought season, given its live storage.

The numbers make for grim reading. A country is classified “water stressed“ if per capita availability is less than 1,700 cubic metres. In India, the reading against this parameter is 1,545 cubic met res. Factoring multiple variables, including population, the ministry predicts availabi lity could fall to 1,341 cubic metres in 2025, and even plummet to 1,140 cubic metres in 2050, which is perilously close to a “water scarcity condition“ (per capita availability of less than 1,000 cubic metres).

While the prevailing bleak situation can be attributed to successive droughts, the condition is largely a consequence of overexploitation and pollution over the years. With 68 crore people -56% of the country's population -relying on groundwater, the government has also been encouraging borewells.

Another set of documents from the ministry of drinking water and sanitation throw another disturbing fact into stark relief: water in 320 of the 640 districts in the country is contaminated. Among the pollutants are fluoride, arsenic, other chemicals and hea vy metals such as chromium and lead. Contaminated water affects more than 6 lakh habitations directly , while many more are adversely affected indirectly . According to the Union health ministry , five diseases that result from water contamination have claimed more than 18,000 lives in the past seven years.

S S Hegde, senior scientist with the water resources ministry , told TOI, “There are two kinds of pollution: geogenic (caused by nature) and anthropogenic (resulting from human activity).Chemicals such as fluoride and arsenic are largely geogenic. But, there is a water problem, and it's largely because of overexploitation.As far as pollution is concerned, some of these chemicals cannot be treated with available technologies.“

Droughts in India

Graphic courtesy: The Times of India

See graphic:

Some facts: Droughts in India

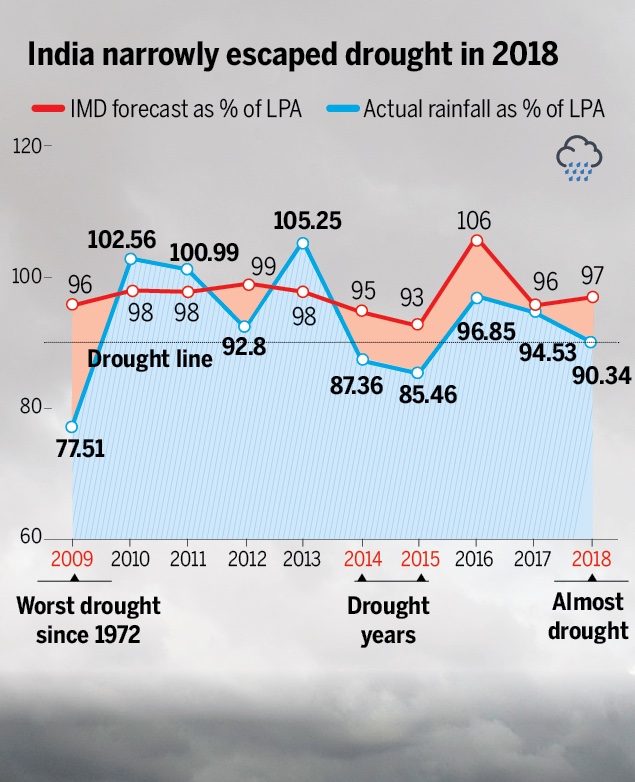

India’s drought years: 2009-18

From: February 12, 2020: The Times of India

See graphic, ' 2009-18: the years in which India was affected by drought'

Drought-proofing in India: 1960s-90s

Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar

Drought not a big calamity in India anymore

The monsoon has failed badly this year as it did in 1965.But its little more than an inconvenience this year,whereas in 1965 it was a monstrous calamity.The drought-proofing of India is a success story,but one widely misunderstood. India in the 1960s was pathetically dependent on US food aid.Even in the bumper monsoon year of 1964-65,food aid totalled 7 million tonnes,over one-tenth of domestic production.Then India was hit by twin droughts in 1965 and 1966.Grain production crashed by one-fifth.Only unprecedented food aid saved India from mass starvation.Jawaharlal Nehru talked big about self-sufficiency.Yet he led India into deep dependence on foreign charity.The 1966 drought drove India into a ship-to-mouth existence.Hungry mouths could be filled only by food aid,which reached a record 10 million tonnes. Foreign experts opined that India could never feed itself.William and Paul Paddock wrote a best-seller titled Famine 1975,arguing that the world was running out of food and would suffer global famine by 1975.They said aid-givers couldnt possibly meet the food needs of high-population countries like India.So,the limited food surpluses of the West should be conserved for countries capable of being saved.Countries incapable of being saved,like India,should be left to starve,for the greater good of humanity.

Indians were angered and horrified by the book,yet it was widely applauded in the West.Environmentalist Paul Ehrlich,author of The Population Bomb,praised the Paddock brothers sky-high for having the guts to highlight a Malthusian challenge. The US was never happy with Indias non-alignment.President Johnson made Indian politicians and officials beg repeatedly for more food.This prevented mass starvation,but left Indians writhing with humiliation. Then came the green revolution.This,it is widely but inaccurately believed,raised food availability and ended import dependence.Now,the green revolution certainly raised yields,enabling production to increase,even though acreage reached a plateau.But it did not improve foodgrain availability per person.This reached a peak of 480 grams per day per person in 1964-65,a level that was not reached again for decades.Indeed,it was just 430 gm per day per person last year.Per capita consumption of superior foodsmeat,eggs,vegetables,edible oilsincreased significantly over the years.But poor people could not afford superior foods. How then did the spectre of starvation vanish Largely because of better distribution.Employment schemes in rain-deficit areas injected purchasing power where it was most needed.The slow but steady expansion of the road network helped grain to flow to scarcity areas.The public distribution system expanded steadily.Hunger remained,but did not escalate into starvation.By the 1990s,hunger diminished too. Second,the spread of irrigation stemmed crop losses.The share of the irrigated area expanded from roughly one-third to 55% of total acreage.Earlier,most irrigation was through canals,which themselves suffered when droughts dried up reservoirs.But after the 1960s,tubewell irrigation rose exponentially,and now accounts for four-fifths of all irrigation.Tubewells are not affected by drought. More important,tubewells facilitated rabi production in areas with little winter rain.Once,the rabi crop was just one-third the size of the kharif crop.

Today both are equal.This explains why in 2009,which witnessed one of the worst monsoon failures for a century,agricultural production actually rose 1%: good rabi production offset the slump in kharif production. However,arguably the biggest form of drought proofing lies outside agriculture.Rapid GDP growth has dramatically raised the share of industry and services.Agriculture accounted for 52% of GDP in 1950,and for 29.5% even in 1990.This is now down to just 14%.Even if one-twentieth of this is lost to drought,it will be less than 1% of GDP. Back in the 1960s,India couldnt afford to import food,and depended on charity.But today GDP is almost $2 trillion,exports of goods and services exceed $300 billion and forex reserves are $280 billion.Even if we had to import 10 million tonnes of wheat at todays high prices,the cost,$3 billion,would be easily affordable.In fact,no imports are needed: government food stocks exceed 80 million tonnes. This is the real reason that droughts have ceased to be calamities.Foodgrain availability remains as low as in the 1960s,despite the green revolution.But rapid GDP growth,by hugely boosting the share of services and industry in GDP,has made agriculture a relative pygmy,greatly reducing the economys monsoon dependence.There remains a catch: a drought may no longer mean mass starvation,but still means food inflation.

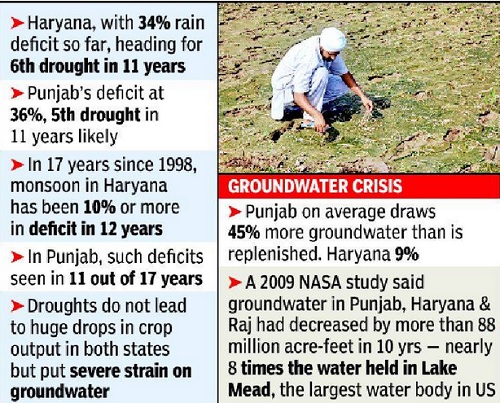

Punjab and Haryana: Drought years since 1998

The Times of India, Sep 05 2015

Amit Bhattacharya & Ikhhlaq Singh Aujla

Haryana faces 6th drought, Punjab 5th

As monsoon begins to withdraw from northwest India, the grain bowl states of Punjab and Haryana head for yet another drought -the fifth and sixth, respectively since 2004. In an alarming trend over the past two decades, the two states have consistently received below normal monsoon rainfall since 1998.

Out of 17 years since 1998, Haryana has received at least 10% below normal monsoon rains in 12 years. The corresponding figure for Punjab is 11 of out 17 years, counting the present year as deficient.

Punjab currently has a monsoon shortfall of 36% and Haryana 34%. These deficits are likely to grow as little rain is expected after the monsoon withdraws. Last year the two states received around 50% of normal monsoon rainfall.

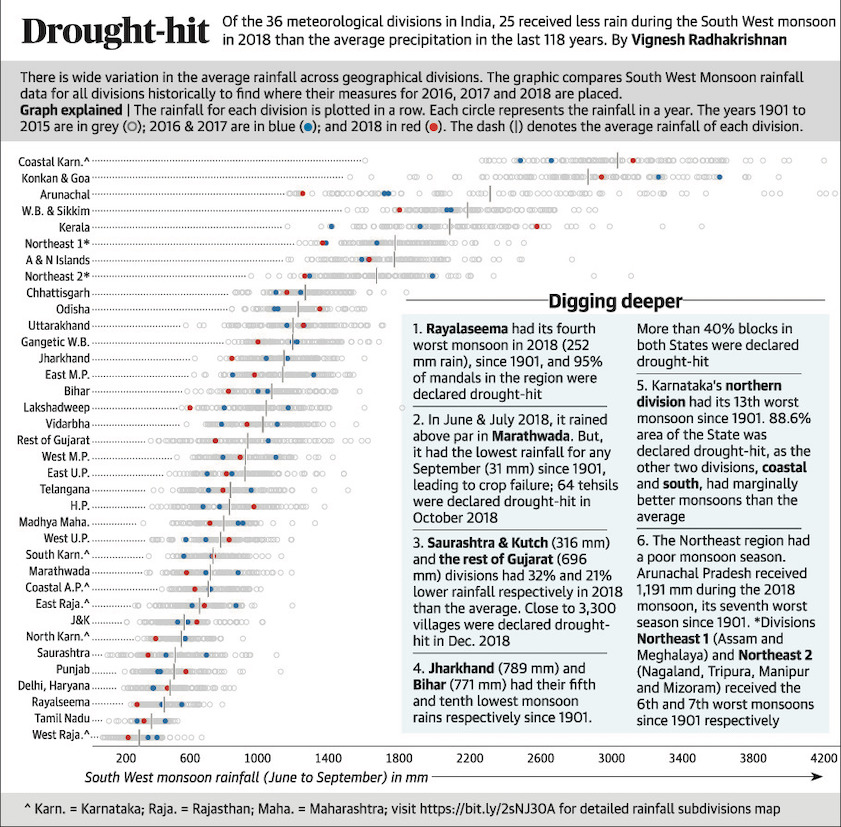

2016- 18, rainfall for all geographical divisions

From: January 30, 2019: The Hindu

See graphic:

The graphic compares South West Monsoon rainfall data for all geographically divisions historically to find where their measures for 2016, 2017 and 2018 are placed

2000: `Europe's pollution caused drought in India'

'The monsoon's bountiful rain is crucial to the economy and to livelihoods in the region'

Pollution from Europe helped cause a drought in India that was one of the country’s worst ever natural disasters, affecting more than 130 million people, according to new research.

Sulphur dioxide – produced mainly by coal-fired power plants – causes a number of harmful effects, such as acid rain, heart and lung diseases, and damage to plant growth.

But sulphate aerosols also have a cooling effect on the atmosphere because it reflects sunlight back into space, a property that has led some to suggest it could be used as a form of ‘geo-engineering’ to reduce the rate of global warming.

However, emissions from the northern hemisphere can change the relative rate of warming in the south, causing the tropical rain-band to shift – with potentially devastating results.

Now researchers at Imperial College London have calculated just how big an effect emissions of sulphur dioxide had on rainfall in India in 2000.

The north-west of India experienced a staggering drop in precipitation of about 40 per cent because of emissions from the northern hemisphere’s main industrial areas.

Europe’s emissions alone caused reductions of up to 10 per cent in the north-west and south-west regions.

One of the researchers, Dr Apostolos Voulgarakis, of ICL’s Grantham Institute, said the study showed how emissions in one part of the world could have a significant effect on another – even if the pollution itself didn’t actually get there.

“East Asia is contributing more [of an effect] because it’s closer, but there is an effect from Europe and also the US,” he told The Independent.

Dr Voulgarakis said their research, along with other studies, showed the kind of problems that might result from attempts to use sulphur dioxide in a geo-engineering scheme.

“Geo-engineering has generally suggested to be problematic because of the knock-on effects it could have,” he said.

“This research shows one of those reasons as it can affect rainfall quite dramatically.”

The figures were produced using a climate model which Dr Voulgarakis said tended to give results on the high side of the range produced by different methods.

10 photographs to show to anyone who doesn't believe in climate change 10 show all A briefing note prepared by Grantham researchers about the techniques to assess air pollutants said they could have “complex and diverse” effects.

Sulphate aerosols could “cool the atmosphere and so off-set some global warming” but “also increase air pollution levels and cause drought”.

“The impacts of short-lived pollutant emissions on air quality and climate change vary greatly depending on both the region where emissions occur and the location of the affected region,” it said.

“The climate effects of air pollutants are best assessed on a region-by-region basis, and are not easily captured by global metrics.”

It suggested air pollution and global warming should be dealt with as a single issue.

“Air quality and climate policy should be designed simultaneously to maximise beneficial outcome,” the briefing note said.

As the harmful effects of sulphur dioxide became clear, the European Union worked to reduce emissions.

A switch away from fuels with high levels of sulphur saw a 74 per cent reduction between 1990 and 2011.

By 2011, sulphur dioxides were less than half the amount in 2000.

In a blog post, Dilshad Shawki, a PhD student at the Grantham Institute, described how important understanding rainfall was, particularly in India and the surrounding area.

“Each summer the South Asian monsoon drenches the Indian subcontinent, as strong moisture-laden winds from the Indian Ocean deliver over 70 per cent of the region’s annual rainfall in just three months.

“As such, the monsoon’s bountiful rain is crucial to the economy and to livelihoods in the region.

“In recent decades however, rising pollution levels and increases in global surface temperatures have influenced atmospheric circulation patterns in the tropics, in turn affecting monsoon rainfall patterns.

“The challenge for scientists, including myself, is to gain a better appreciation of these relationships in order to build more accurate forecasts. Understanding and predicting monsoon rainfall is of huge importance to those societies that have developed following its rhythms.”

Despite the fall in European sulphur dioxide emissions, India’s droughts have continued as the world has got warmer.

In 2016, the country saw its highest temperature on record – a sweltering 51 degrees Celsius (123.8F). Hundreds of people died as crops failed in more than 13 states.

Tens of thousands of small farmers also abandoned their land and moved to cities, while others killed themselves rather than face life in an urban shanty town.

Impact of droughts on economy

In general

Pradeep Thakur, June 19, 2021: The Times of India

A special report on ‘Drought 2021’, released by the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), has said the Deccan plateau is seeing the highest frequency of droughts in India. It has estimated the “impact of severe droughts on India’s GDP to be about 2-5% per annum”, despite decreasing contribution of agriculture in the country’s expanding economy.

The study — Global Assessment Report (GAR) on Drought 2021 — has looked into rising water stress across the globe and resulting migration and desertification. The experts, commissioned by UNDRR, conducted case studies in the Deccan plateau, comprising 43% of India’s landmass.

“The Deccan region sees the highest frequency (of more than 6%) of severe droughts in all of India,” the report has said and the cascading impact continues over the next several years. For instance, the report said in recent major droughts in Tamil Nadu, a 20% reduction in the primary sector caused an overall 5% drop in industry and a 3% reduction in the service sector. “Drought is on the verge of becoming the next pandemic and there is no vaccine to cure it. Drought has directly affected 1.5 billion people so far this century and this number will grow dramatically unless the world gets better at managing this risk,” said Mami Mizutori, head of UNDRR.

The study found “significant drought conditions” once in every three years in the Deccan plateau leading to largescale migration and desertification. A 2019 case study revealed “villages in Maharashtra and Karnataka’s districts were deserted as families left due to acute water crisis,” the report said. “Most of the world will be living with water stress in the next few years,” said Mizutori, cautioning policymakers to be better prepared as industrialisation and urbanisation would only lead to ‘demand outstripping supply’.

In 2016

The Times of India, May 11, 2016

Drought in 10 states is estimated to impact the economy by at least Rs 6,50,000 crore as about 33 crore people across 256 districts are facing the grave situation, a study has revealed.

Due to two consecutive years of poor monsoon, 2014-15 and 2015-16, water shortage in reservoirs as well as lowering of ground water table has created a serious challenge for the drought-affected areas in 10 states like Maharashtra and Karnataka, the study by Assocham said.

"The rough estimate indicates that this drought will cost national economy at least Rs 6,50,000 crore or say $100 billion," it said. The impact of drought is likely to remain for at least six months more because one needs resources and time to revive the activities on ground even if monsoon is predicted to be normal this year, it said.

"Let us assume, the government will spend just Rs 3,000 per person to cover water, food, health for these people for one or two month. With the population of 33 crore at risk, the estimated cost to economy will be about Rs 1,00,000 crore per month," the study said.

The loss of subsidies on power, fertiliser and other inputs multiply the impact, it added. On economic impact of drought, the study said the financial resources get diverted from development to aid and the possible migration to other places puts pressure on urban infrastructure and supplies.

There is likely an impact on children and women health besides farm debt increase due to loss in livestock and farm economy in the drought-hit districts, it said. The drought would create inflationary pressures making the food management an imperative challenge for the government and the policy makers, he added.

Central aid for drought stricken states

2012-16

The Times of India, Apr 19 2016

It's a drought when it comes to funds too

Subodh Varma

Relief and compensation for farmers and labou rers in 10 drought stricken states has become embroiled in an unseemly game of pass-the-buck as cashstrapped states are demanding funds to the tune of nearly Rs 42,000 crore from the Centre which has -so far -coughed up just about a third of that, nearly Rs13,000 crore. This appears to be stan dard practice: in the previous year, 2014-15, which was also a drought year, five affected states had demanded nearly Rs 18,000 crore while the Centre had doled out Rs 3,350 crore.

Long-term trends show that relief and compensation after natural calamities, which is primarily the responsibility of states, has been eating up an increasing share of state government budgets.For all states put together, such spending has increased by over three times in the past 15 years, with some states prone to droughts and floods having to spend even more. In 2001-02, the states spent Rs 5,012 crore on providing relief to people from natural calamities, but this had zoomed up to Rs 20,220 crore in 2014-15.

The Centre's share, which is in addition to this, comes from the National Disaster Relief Fund, which was mandated by the 13th finance commission to have Rs 33,581 crore for 2010-2015.Subsequently , the 14th finance commission increased this to Rs 61,219 crore for 2015-20.The Centre also contributes to state disaster relief funds.

Since less than a quarter of the cropped area in India is covered under any kind of insurance and also because the sum insured is a frac tion of the cost of produce, any weather calamity like drought or hailstorms can spell ruin for farmers.

For the financial year 2015-16, states had budgeted only Rs 13,240 crore for relief from natural calamities.

This is likely to be ex ceeded by a conside rable amount in view of the drought that is spread across 251 dis tricts of the country .

With winter rains fai ling in many parts, the drought has further intensified. The Karnataka government has already declared 12 districts as drought-affected for the rabi (winter) season which were part of the 27 drought districts for the preceding kharif (summer) season.

So, why is there such a big discrepancy between the states' demands and the Centre's approvals? Central go vernment officials say an inter-ministerial team visits the drought-affected area in each state and makes an assessment which is the basis of approval for relief funds.

State government officials unhappy with the huge difference say that their assessments are more rooted in reality and the Centre always has a tendency to undercut their claims.

The Modi government had lowered the minimum damage limit from 50% to 33% for farmers to become eligible for compensation and it has also increased the rate of compensation from Rs 9,000 to Rs 13,500 per hectare with a cap of two hectares.

But reports from most states say that even the increased amounts are not sufficient owing to the much sharper increase in costs of fertilisers, seeds, pesticides and other inputs.