Abhijit Banerjee

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

From: Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

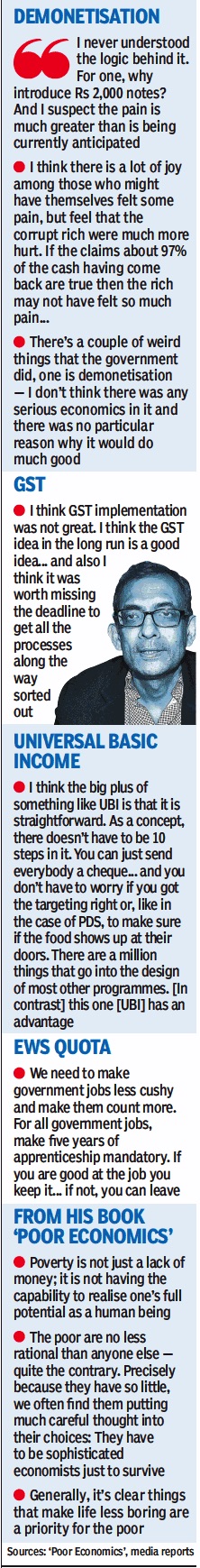

See graphic:

Thus Spake Abhijit Banerjee

From: Dec 11, 2019: The Times of India

See picture:

Abhijit Banerjee receives the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel from King Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden during the award ceremony in Stockholm

Contents |

Early life

Schooldays and football

Prithvijit Mitra, Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

Teachers and classmates at South Point High School — alma mater of Nobel laureate Abhijit Banerjee — remember him as a ‘skinny, sober boy who wore thick glasses and loved football’. As the news (of Banerjee winning this year’s Nobel) flashed on TV screens, they erupted in joy and got in touch with each other to celebrate. The school authorities invited senior teachers who taught Banerjee to share their memories. A congratulatory note will be sent to him after the school reopens from vacation.

“It’s a great Puja gift and nothing could possibly make the school feel more proud. South Point’s name has been etched in the international scene, thanks to Banerjee. It is an honour for us and the students that he walked down these corridors. This is the ultimate recognition and we are privileged to be associated with him in his hour of glory,” said principal Rupa Sanyal Bhattacharya.

Biology teacher Sharmila De Sarkar, a classmate of Banerjee, said she was overwhelmed with joy after hearing the news. “Abhijit had been in reckoning for Nobel for some years now and this was expected. But when I heard about it, I couldn’t hold my tears. We were classmates for four years till Class X, but the friendship and bonding remained intact till we left school,” said De Sarkar.

Although never a topper, Banerjee was a ‘good student who was very strong in mathematics’, recalled mathematics teacher Dipali Sengupta. “He stood out probably due to his demeanour and quiet nature. He wore thick glasses and was serious about his studies,” she said.

But the studious gait was misleading, claimed De Sarkar. “He was passionate about football and played regularly in his neighbourhood. He would invariably share his exploits on the field with us the next day in school. We would pull his leg but he took himself seriously as a footballer,” she added.

From the Indian Statistical Institute to Presidency

Zeeshan Jawed, Dwaipayan Ghosh & Somdatta Basu, Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

As the news broke, Presidency — which has now produced two economics Nobel winners — was being talked of as “the college Abhijit Banerjee almost didn’t attend”. But the campus was bursting with joy at the feat of its famous alumnus.

Abhijit, who on Monday joined Amartya Sen in the hallowed ranks of economics Nobel laureates from Presidency College (now Presidency University), had initially joined the prestigious Indian Statistical Institute (ISI), but left it after a week to pursue economics at Presidency, where his father, Dipak Banerjee, taught the subject.

“We are overjoyed,” said Presidency vice-chancellor Anuradha Lohia. “Abhijit is a celebrated economist worldwide.” She mentioned how he had a deep relationship with the now 202-year-old venerable College Street institution, starting from his father’s contributions to the way he helped the college become a university. “Dipak Banerjee was a legendary professor of economics at Presidency College, and Abhijit has instituted a lecture series in his name. Abhijit himself has also been very involved and a guiding force as the college transitioned into a university. His writings reflect a deep sense of pride for his alma mater. In the bicentennial celebrations (of 2017), he wrote on how a college graduated into a university and how Presidency has always remained different because it was formed by secular citizens.”

Within an hour of the Nobel announcement, the university put up a congratulatory message on its website. It also congratulated Esther Duflo. “We will plan how to honour him once the university reopens,” said Presidency registrar Debajyoti Konar.

There were several stories being shared on social media — mostly by Abhijit’s contemporaries — about his campus days. One such tale goes that once, Dipak Banerjee, exasperated with his class, burst out: “Tomrashob gadhar bachcha (You are all donkey’s offspring).” Abhijit, who was in attendance, quipped: “Baba, amio ekhane achhi (I’m also here)” .... to which Dipak, without batting an eyelid, said: “Toke chhara shob(All but you)”.

“It is surreal — two Indians getting the economics Nobel from the same alma mater,” Lohia added. “Our institution is truly special.... We are proud of Abhijit. We congratulate Esther Duflo for her significant contribution.”

Abhijit was also a member of the university’s mentor group, which handheld the institution’s journey to becoming a university in 2011. Amartya Sen was the adviser to the chair of the group. He was also instrumental in organising the Dipak Banerjee Memorial Lecture every year, which have been attended by, among others, Amartya Sen and former RBI chief Raghuram Rajan.

“It is a tremendous feeling to know that professor Banerjee has been bestowed with such a great honour,” said Mousumi Dutta, professor and head of the economics wing. A proud alumni association called Abhijit’s achievement “monumental”.

Several of his classmates felt that the college knew how to groom the best students. “I clearly remember how Dipak Banerjee used to call me over to his residence. We both shared a passion for mathematics and two of our professors — Mihir Kanti Rakshit and Nabyendu Sen — took extra time out to explain how to merge economics with mathematics. We were even asked to share answer scripts to understand our strengths and weaknesses. Landing up at a professor’s residence was always welcomed,” recalled Abhijit Pathak, his close friend from college.

JNU: Agitation landed him in jail

Shankar Raghuraman , Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

Abhijit Vinayak Banerjee — the name reflecting his mixed Bengali and Maharashtrian parentage — was even as a student in JNU in the early 1980s clearly destined for big things, though just how big his contemporaries may not quite have realised at that stage. When he finished his MA in economics, he was not just the topper of his batch but was talked about as having “broken the record” for the best grades ever in the Centre. Exactly what that meant in quantitative terms may not have been very clear to anybody, but at the very least it did tell you that he was among the best of JNU economics MA students of all time, if not the best.

But there was much more to Abhijit than just being a cracker at economics. While he could come across as a touch arrogant to those who did not know him well, his friends — and there were many and of varied sorts — would vouch for the fact that he was one of the warmest people you could know.

In a Centre where the vast majority of students venerated teachers like Prabhat Pattnaik, Krishna Bharadwaj and Amit Bhaduri, Abhijit was not averse to sharp exchanges with teachers in classroom, never disrespectful but not given to starry-eyed awe either.

His decision to join JNU when he had the choice of joining the Delhi School of Economics was, as he himself admits, driven more by his attraction for the ambience of JNU than because he thought it would necessarily give him a better grounding in economics. If anything, DSE was the surer passport to an academic future, whether in India or abroad, but then Abhijit didn’t really need easy passage into that world.

Organised student groups strived in vain to enlist him to the cause, Abhijit steadfastly refusing to join any of the mainstream groups on campus — SFI, AISF, Free Thinkers or Samajwadi Yuvjan Sabha. Yet, he was far from apolitical, holding strong views on most things and unafraid to express them. Politically, he was perhaps most comfortable with individuals of a broadly Left persuasion who preferred the freedom of not being part of any organisation and deciding their stance from issue to issue. This political conviction showed up in the agitation in 1983 against a ‘reform’ of the admission policy that would effectively have diluted the affirmative action elements of a policy that had made JNU the university that gave people from humble backgrounds and the back of beyond a real shot at academic attainment and inclusion. He was one of over 300 students who were jailed in Tihar for about 10 days as a result of that agitation.

Abhijit was — and is — also a genuine lover of good food and has the willingness to try new places and cuisines that such people typically have. And he enjoyed his drink as much then as he does today, though he has acquired a more refined taste in liquor than in those days almost four decades ago.

== Esther’s love for Kolkata==Subhro Niyogi , Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

French economist Esther Duflo, one of the three recipients of the Economics Nobel announced, believes Kolkata should preserve its buildings that lend the city its unique character and retain the sheer madness that is visible in public life to wow Western tourists.

In an interaction with TOI during a Kolkata trip four years ago, Duflo had said the city needed to recognise its potential as a tourist attraction and preserve precincts in north, central and south Kolkata where neighbourhoods still retained old buildings that were architecturally distinct.

“Investing in preserving these localities can be financially rewarding,” she said. To buttress her point, she pointed to Prague where a major restoration project had unfolded after the end of Communism. “Many things old — trams, building facades and bridges — were restored. It has paid dividends. Today, Prague is a topdraw tourist destination. Kolkata has the potential to become a Prague,” she had said.

Duflo, who fell in love with Kolkata and its magnificent crumbling mansions and chaos and energy on the streets on her very first visit in 1997 when she was a 24-year-old researcher, said she knew people in the US who were willing to pay a small fortune to experience what Kolkata had to offer. “Western tourists now come to India for Taj Mahal, forts in Rajasthan and Kerala’s backwaters. The madness of Kolkata can be the next big destination,” she remarked.

If there is anything that bothers her during her visits to the city, it is the demolition of remarkable old buildings. “Every time I come, and I have been here more than 20 times, I see one more splendid building gone and replaced by a steel-and-glass structure. Someone needs to put an end to the destruction and fix the crumbling buildings. I hope someone displays the vision to act and save the city,” she said.

Contribution in economics

A life in economics

Chidanand Rajghatta , Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

From: Chidanand Rajghatta , Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

Mumbai-born, Kolkata-bred economist Abhijit Banerjee – an alumnus of JNU – will share the 2019 Nobel Prize in economic sciences with his colleague and wife Esther Duflo and fellow researcher Michael Kremer for their groundbreaking experiment-based research into how to reduce global poverty.

“The research conducted by this year’s Laureates has considerably improved our ability to fight global poverty. In just two decades, their new experiment-based approach has transformed development economics, which is now a flourishing field of research,” the Nobel Prize Committee said in its announcement of the $ 1.1 million prize.

At 46, Paris-born Duflo is the youngest ever – and only second woman (after Elinor Ostrom in 2009) – to win an economics Nobel. She was Banerjee’s doctoral student at MIT.

Currently the Ford Foundation International Professor of Economics at MIT, the 1961-born Banerjee, born to a Maharashtrian mother and Bengali father, and Duflo are best known for anti-poverty research emphasising the use of field experiments.

Banerjee is the second Indian to win an Economics Nobel after Amartya Sen, who was a good friend of his father, the late Dipak Banerjee, who headed Presidency’s economics department. Sen “was very very happy and delighted” at the news.

Abhijit was among those who advised Cong on Nyay

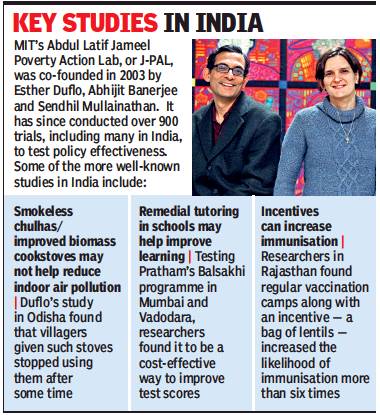

In 2003, Duflo and Banerjee (along with Sendhil Mullainathan, also from India and now of the University of Chicago) co-founded the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), a global network of anti-poverty researchers that conducts field experiments. J-PAL works to both discern which kinds of local interventions have the greatest impact on social problems, and to implement those programmes in cooperation with governments and NGOs. Among J-PAL’s notable interventions are deworming programmes that have been adopted widely.

Much of Banerjee’s work centres on economic policies and research relating to India, particularly in the field of microfinance and financial inclusion. He was among the advisers to Congress on its Nyuntam Aay Yojana (NYAY scheme), proposed ahead of 2019 general elections, which pledged to distribute cash to 20% of India's poorest families as a minimum guarantee program.

Banerjee took a dim view of the Modi government’s demonetisation move and GST implementation, and has cited them among reasons for India’s economic slowdown.

News of his Nobel win was a lightning rod for some partisan-needling in India within hours of the announcement. “Delighted to hear that Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Dufflo have won the Nobel Prize for Economics. Richly deserved. Abhijit is a proud graduate of that much-maligned university, JNU, and his work has inspired many younger Indian scholars,” tweeted the historian Ramachandra Guha, a trenchant critic of the current dispensation.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi congratulated Banerjee on his honour, noting in a brief tweet that “he has made notable contributions in the field of poverty alleviation”. Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, a fellow JNU alumnus, tweeted, “Congratulations #AbhijitBanerjee on being awarded the 2019 Nobel Prize for your contribution for easing poverty. #JNU Also wishing Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer. #Nobel-Prize2019”. Banerjee’s multiple affiliations — Presidency College (Kolkata), JNU, Harvard, Princeton, MIT — allowed everyone to stake a claim to its star winning the Nobel.

“Hearty congratulations to Abhijit Banerjee, alumnus of South Point School & Presidency College Kolkata, for winning the Nobel Prize in Economics. Another Bengali has done the nation proud. We are overjoyed,” tweeted West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee. Amartya Sen, also of Presidency College, and later Harvard, won the Economics Nobel in 1998.

Banerjee and Duflo also became the sixth husbandwife couple to be awarded the Nobel, although some won it together (Marie and Pierre Curie for the discovery of polonium and radium) and some won it separately in different years (Gunnar Myrdal for Economics in 1974 and Alva Myrdal in 1982 for Peace).

By some accounts, Banerjee also became only the third male who is not white to win the top prize in economics (the other two being Arthur Lewis in 1979 and Amartya Sen in 1998).

Banerjee received his undergraduate degree from Presidency and a Master’s from JNU. He earned his PhD in Economics from Harvard University in 1988. He spent four years on the faculty at Princeton University, and one year at Harvard, before joining the MIT faculty in 1993.

Duflo and Banerjee are familiar academics on the India circuit and have published dozens of research papers, together and with other co-authors. They have also co-written two books together, ‘Poor Economics’ (2011) and the forthcoming ‘Good Economics for Hard Times’ (2019).

Trials To Eliminate Errors

Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

From: Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

From: Oct 15, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Seeing big problems in small bits

If you want poor people to take deworming tablets or use anti-malarial bednets — and thus reduce disease — should you make people pay for those products or give them away for free? For years, economists believed it was important to charge at least a small fee so people would value the service.

But field experiments in the late 1990s and early 2000s by Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo, and Michael Kremer helped establish otherwise: subsidies helped increase use of preventative healthcare, they found. Those studies helped shift the World Health Organisation and the UN to promote subsidised healthcare for the poor.

Upturning conventional wisdom is not new to this year’s economics Nobel laureates. Banerjee, Duflo, and Kremer pioneered the use of field experiments into social behaviour to understand and solve problems faced by the poor, especially with randomised control trials (or RCTS, used to test drugs), in which an intervention is assigned to one of two similar groups to test its effectiveness. In doing so, they brought what the Nobel committee called “a new approach to obtaining reliable answers about the best ways to fight global poverty”.

Development economics is split between those who believe that external aid is necessary to help people out of poverty traps, and those who think that this would distort local capacity to find their own solutions. RCTs brought a more fine-grained “evidence-based approach” to development research by randomly choosing groups, running experiments, and evaluating effectiveness of an intervention. Their topics have ranged from how to fix teacher absenteeism to corruption in issuance of driving licenses.

Kremer used this approach in western Kenya in the late 1990s; in 2003, Banerjee and Duflo, along with Sendhil Mullainathan, set up the Abdul Lateef Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) at MIT.

When Banerjee and Duflo’s experiments were first began to be published 20 years ago, their findings often ran counter to popular thinking in international development circles. Their studies helped demolish darlings of the global aid industry such as smokeless chulhas and microfinance (see box).

But their methods have become hugely influential, especially with the publication of their book ‘Poor Economics’.

Randomised experiments offered policymakers and donors what Bill Gates called “an empirically rigourous” way to find solutions that could be scaled up or ones that should be scrapped or avoided. In 2016, some 400 projects financed by World Bank were being evaluated by randomised trials. J-PAL alone has run 941RCTs in 81countries on everything from agriculture and crime to education and health. According to the lab, their evaluations have helped scale up welfare programs to reach 400 million people globally.

Not everyone is a fan of the “randomistas”, however. Economists like Angus Deaton and science philosopher Nancy Cartwright have noted randomised trials don’t produce generalisable results — what works in one place may not work in another.

2016: Delhi’s Chunauti plan

Oct 14, 2019: The Indian Express

Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal said that Nobel Prize winner Abhijit Banerjee was the inspiration behind the Delhi government’s education reform scheme — Chunauti — to put a check on dropout rate of the students. Congratulating the eminent economist who received the prestigious award on Monday, Kejriwal, said that his government’s work in education which is a “success story” for the government school education had a close link with Banerjee.

“Abhijit Banerjee’s pathbreaking work has benefitted lakhs of children studying in Delhi govt schools. One of our most important education reform Chunauti has transformed govt school classroom teaching. It is based on the model developed by him. Big day for every Indian. His work on poverty alleviation gets highest endorsement (sic),” Kejriwal said in a series of tweets.

The AAP government had introduced the scheme in 2016 seeking to check student dropout rates and improve the quality of education with special focus on the weakest students. The state government also announced a subsequent version of the scheme ‘Chunauti 2018’ under which students from Class 6 to 8 are mapped and their learning levels are enhanced. Meanwhile, Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia also congratulated Banerjee for his work for school education and poor children.

“He worked a lot for the education of poor children, especially those in government schools...those who are lagging behind in their reading level. He is an inspiration for us. I congratulate him and also thank him on behalf of Delhi government,” Sisodia said. Banerjee along with his wife Esther Duflo and economist Michael Kremer won the 2019 Nobel Economics Prize “for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty”.

What is the Chunauti scheme?

The plan divides students into groups on the basis of who can read and write Hindi and English, and solve mathematical problems. Based on their learning abilities, they are given special classes, in govt and MCD schools.

2017: The Economist as Plumber: could not convince Kerala on RCT

Oct 16, 2019: The Times of India

THIRUVANANTHAPURAM: Their efforts to revive development economics, particularly through the popularisation of ‘randomised control trials’ (RCT) has won Abhijit Banerjee-Esther Duflo couple the Nobel Prize in Economic sciences in 2019. But the famed economists had failed to impress the government of Kerala when they visited the state and proposed the application of RCT to scientifically deduce the potentiality of Ardram Mission project that was conceived to convert primary health centres to family health centres.

In one of her papers ‘The Economist as Plumber’ published in 2017, Duflo explained the ordeal that she, Banerjee and Gita Gopinath, IMF chief economist and former adviser to Kerala chief minister, had to face when the trio dropped in at the secretariat on an invite to discuss the project.

Duflo explains in detail how indifferently a retired professor who was in charge of the implementation of the project took their questions. “It turns out that policy makers rarely have the time or inclination to focus on them, and will tend to decide on how to address them based on hunches, without much regard for evidence,” she said. She said the former additional chief secretary (health) Rajeev Sadanandan could spent only a little time with them and had left them with a retired professor in charge of the project implementation for interacting with them. The interaction was, however, disparaging, she said.

“Abhijit Banerjee, Gita Gopinath and I recently spent a few hours with bureaucrats and consultants from the health department in the state of Kerala, in the south of India. Kerala is one of India’s most successful states, at least as far as the social sector. It is starting to face first-world problems: an aging population, high prevalence of hypertension, diabetes and obesity... Their best idea is to reform the public primary health care system in order to make it more attractive to customers (who for the most part seek their health care in the private sector, like elsewhere in India), and to instate better practices of prevention, management, and treatment... Though the additional chief secretary (top bureaucrat) in charge of health had invited us to the meeting, he was called away to deal with a doctors’ strike around the time the conversation turned to the specifics of the reform. He handed us over to a retired professor and a retired doctor, who have been charged with designing the specifics of the policy. This in itself is symptomatic: top policy makers usually have absolutely no time for figuring out the details of a policy plan, and delegate it to ‘experts’,” she said in the paper.

“In our conversation, we started to push on some specific questions on the model that they had in mind: why would patients pay attention to a nurse, given that until now they have only taken doctors seriously?...What was striking was, not only did they not have any answer to these questions, but they showed no real interest in even entertaining them, ” she added.

Contributions

Healthcare/ 2018

Oct 14, 2019: UChicago Center in Delhi

A group of economists, both from India and abroad, and both from industry and academia, outlined an economic agenda for the country over the next five years. By setting out some of the key challenges as well as outlining proposals well before the coming elections, the intent was to spur debate and discussion.

The economists were Abhijit Banerjee, Pranjul Bhandari, Sajjid Chinoy, Maitreesh Ghatak, Gita Gopinath, Amartya Lahiri, Neelkanth Mishra, Prachi Mishra, Karthik Muralidharan, Rohini Pande, Eswar Prasad, E. Somanathan, and Raghuram Rajan.

Critiques

How their partners view the couple’s experiments

How Banerjee and Duflo’s partners in India view their experiments, Oct 22, 2019: The Times of India

Development Stakeholders Who Have Applied Randomised Controlled Trials Note Its Strengths And Also The Challenges With Using The Approach

Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo, this year’s economics Nobel laureates, refined their techniques in India, working on the field with organisations like Seva Mandir and Pratham.

Seva Mandir is an Udaipur-based NGO that works across areas like nutrition, health, education, gender and environment. Banerjee, who was friends with its former president Ajay Mehta, began using his randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in the mid-1990s to help Seva Mandir answer some niggling problems that plagued their work in a complex tribaldominated region.

One of the most famous RCTs conducted for Seva Mandir was about how a combination of cameras and pay incentives could reduce teacher-absenteeism in their schools. Some disagreed with the experiment ideologically, saying it was more important to improve the teachers’ intrinsic motivation rather than use these external pressures. The teachers for their part were persuaded, even if reluctantly, into being part of the experiment.

But the experiment with cameras and incentives clearly worked to stem absenteeism and Seva Mandir gained greatly from this study specifically and, even more, from the process of collecting and analysing evidence.

“I have huge respect for the way they spend time collecting and cleaning the data, piloting their questionnaires themselves. They were closely connected to the ground,” says Priyanka Singh, former CEO of Seva Mandir and now CSR head at InterGlobe Enterprises. But Singh’s takeaway from their painstaking research is that “evidence can help you change things, if you are located in an institution open to change”.

Interestingly, the same methods, when applied to a large-scale government setting, did not work. The attempt to use the camera and incentives model for nurses in the Rajasthan government’s health subcentres yielded no results — Duflo’s paper on the experiment likened it to applying a “Band-Aid on a corpse”.

Randomisation takes care of many problems of context, so caste and other social dynamics do not muddy the results, says Singh, but admits that RCTs have their uses and their limitations. They run for a period of 20-22 months; the setting they operate in is not a blank slate but a place where NGOs have worked.

For instance, she points out that in 2009, “the central government’s National Rural Health Mission recruited nurses on a large scale, leaving very few, under-trained nurses from private colleges for the NGO to work with, which cramped its immunisation camps. This supply problem suddenly shifted the context”.

Such background issues are not always factored in when it comes to the RCT approach. All solutions need recalibration, for which you do need “longterm work in a community and sustained leadership,” says Singh.

Another organisation that has worked closely with Banerjee, Duflo and J-PAL (Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab), the poverty research centre they co-founded, is the education NGO Pratham. “We have had a long association of 20 years, from when we were in an early stage ourselves,” says Rukmini Banerji, the Pratham CEO.

J-PAL evaluated the Balsakhi remedial teacher programme that Pratham ran for municipal schools in Mumbai and Vadodara. Over the years, they did six RCTs with Pratham, from asking whether a state-mandated participatory committee really improved educational awareness, to what could be done to teach at the right level (TARL), so that children did not fall behind in primary school. “Methodologically, it was a very productive experience to work with J-PAL, they brought real rigour and helped share learnings across contexts,” says Banerji.

For instance, the stringent tests that Pratham put its programmes through, and its impact on learning increases as attested to by J-PAL’s reaserch, seemed useful for educators in Africa who wanted to collaborate with the organisation.

NOT CRITICISM-PROOF, BUT USEFUL ENOUGH

A randomised controlled trial is a type of scientific experiment mainly used in drug trials. It is designed to identify the effectiveness of a treatment and eliminate certain kinds of bias

Subjects are randomly split into groups, one is the treatment group that receives an intervention; the other the control group, which is left alone. The usefulness of the treatment is assessed in comparison to the control group

RCTs have been criticised for not offering solutions that can be generalised. The problem, it’s argued, lies in expecting sweeping answers from RCTs; if their limits are understood, and learnings added to, they can provide useful evidence to drive development.

Desserts

Abhijit Banerjee, Nov 24, 2021: The Times of India

As anyone who has sat down to eat knows, life is never quite so simple: you have your budget for carbs, your budget for sugar, your budget for fat. There is a budget for the amount of attention you can lavish on your attractive neighbour at the dinner table without your partner getting upset; a budget for how long you get to hold forth before your boss gets annoyed; a budget for how often you will have to get up to serve water to M or dessert to N; a budget for patience when your children misbehave; and a budget for fortitude when your charm offensive is not working. Many, many, many budgets, many, many, many choices, all laying claim to your limited stock of decisiveness, often at the same time.

My friends Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir’s wonderful book Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much compellingly argues that the constant pressure of making difficult choices is one of the prime disadvantages of being poor: another ride on the merry-go-round for your expectant children at the risk of not being able to pay the electricity bill? Skip work when your child is sick, or leave her home alone? Skip dinner, or throw yourself at the moneylender’s feet? And a million other dilemmas that those of us who are not poor never have to face.

The thesis of Scarcity is that being in this state of constant anxiety makes it hard for poor people to be productive; they show evidence that the poor are actually better than the less poor at the day-to-day maths of financial choices precisely because they are so obsessed by them, but this diversion of attention makes them worse at many of the other things that are part of being economically successful.

One reaction to this relentless demand for economic rationality is an occasional act of defiance, the unexpected ice cream for your children, the cake that you should not have bought, the double dose of sugar in your guest’s tea, just to prove, mostly to yourself, that you can, that you are still able to be generous and free.

When I was growing up in Kolkata in the 1970s and money was short all around, many of the mothers in my neighbourhood would skip the milk and sugar in their own tea to be able to make a few extra spoons of kheer, so that they could say to us ‘Mishti-mukh kore jabi na?’ (Won’t you please sweeten your mouth before you go?) We never said no, instinctively sensing their need to be able to do this (or perhaps we were just greedy).

I have often wondered why it was important for them that it be something sweet. Or, for that matter, why are meals supposed to end in dessert? Is it precisely because desserts are never consumed for the nourishment? Is it exactly that freedom, that brief moment after the nutrition part is done, when we allow ourselves to temporarily kick off our shoes, forget the weight of responsibilities sitting on us, and indulge?

Or could it be something slightly different (why not both)? Is it the fact that sweet things are easy? Our mouths keen to them, feeling no challenge, offering no resistance, the perfect antidote to stress. After all, the meal went okay. The food was good, the children behaved splendidly, the guests seemed happy enough and the conversation didn’t veer into dangerous political terrains. You breathe a sigh of relief (privately, of course) and serve dessert. You promise yourself that you will only have a spoon. Or two. It is good, isn’t it? Well, one more. Just one. The conversation gets more absorbing. You listen, spoon in hand. How did it get finished? Was that you scraping the pie plate for those tasty scraps? What happened?

My philosophy of desserts is that this is inevitable. All the more because cooking sweet dishes tends to be stressful. There is always the risk that the cake turns out to be too dry, the mousse refuses to set, the custard is lumpy or that the milk that you were boiling for the kheer you’ve been dreaming of finds a way to burn in those three minutes that you were away comforting your daughter.

And once that happens, there is often no way to rewind, unlike with regular stove-top savoury dishes, where a squeeze of a lemon, an extra glug of olive oil, a dousing of coconut or a garnish of toasted nuts often comes to the rescue. With a cake or a pudding, once you stick it in the oven or the fridge, things are largely out of your hands. So, when the dessert is served and your guests seem happy, it is only human to let down your guard.

Your best bet is probably just to plan for it. On the days when you feel the desire to cut back, make as little as you can get away with (assuming your guests do not mind). Serve small portions, with small spoons, keeping the reserve elsewhere. If you are really restricted on sugar, try to think of what you can make with sugar substitutes, or what is less sweet. But then relax – enjoy what is on your plate, savouring every little spoon as it deserves to be. Go to bed happy.

How to make: CHEATER’S TRIFLE

The word trifle apparently comes from the old French word ‘trufle’, meaning a trick or a cheat. I love cheating when I cook. The longer the recipe, the grander its title, the greater the insistence on absolute fealty to some hoary tradition, the more fun it is to try to cut corners.

My aunt, in the days when none of us had any money, would make a trifle from digestive biscuits, a couple of gulps of army rum, runny custard and whatever fruits happened to be at hand (sliced bananas and peeled segments of tangerines, bits of mangoes or sapota, peeled grapes cut in half, apples or pears for some change of texture). It was delicious and it convinced me to try my own luck. This is my version, a cheat that comes together in 20 minutes if you pick the fruits right.

• 20 ladyfinger biscuits, or enough stale cake, in slices about 1 cm thick, to cover the bottom of your trifle dish. Plain is ideal, but at a pinch, a lemon cake or even a plainish fruit cake works.

• 6 tbsp sweet sherry, or Madeira. Don’t go looking for them; Cointreau or Drambuie, port or even rum or whisky will serve if need be.

• 5 cups cut ripe fruit with the juices dribbling out: raspberries, strawberries hulled and halved, nectarines, peaches, plums or mangoes peeled and sliced, grapes or cherries halved and pitted, the flesh from inside the segments of oranges or tangerines, maybe even grapefruit, slices of peeled pears if they are really ripe. The only fruit to avoid may be the blandly sweet, like persimmons or rose apples – a little bit of tart is useful to set off the richness of the custard

• 2 cups whole fruits (blueberries, blackberries, raspberries) for a garnish, if available

• 2 eggs, the whites and yolk separated

• 250 gm mascarpone

• 7 tbsp sugar or other sweetener

• 2 tbsp of whatever alcohol you used already (or why not, something else)

• 1/4 cup sliced almonds, toasted, or some almond (or other nut)- flavoured biscuits, the thinner and crisper, the better, broken into bits, for a possible garnish

Cover the bottom of your bowl with the biscuits or the slices of the cake. The ideal bowl is glass (so that the layers of the fruit will show through the sides) and flat-bottomed, but don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the delicious. Douse the slices with 6 tbsp of the alcohol of choice. Layer the fruit on top, paying attention to mixing them up.

Beat your egg whites with 1 tbsp of the sweetener till soft peaks form (do this first). Without cleaning the beaters, beat the egg yolks with the rest of the sweetener till pale yellow, about 3 minutes, and then add in the extra alcohol and the mascarpone. Beat till well mixed. Then mix in the beaten whites with a gentle hand till you see no more of the white, but make sure that you don’t squeeze the air out of the egg whites. Pour the mixture over the fruits. Garnish with some combination of nuts, bits of cookies and berries. Put in fridge for a few hours to set a bit.

Excerpted with permission from Cooking To Save Your Life (Juggernaut Books)