Sadequain

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Sadequain

Public Murals: Art without social barriers

By Niilofur Farrukh

In the early epochs, art reached its peak in the public realm when artists of the great civilisations created monumental art that survived time and gave it a tangible identity.

Some 20th century artists have tried to resurrect this ethos to acknowledge and engage the masses though mural art.

Two Mexican artists of the 20th century, Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and Jose Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) were active members of the Muralist Movement that was part of the Mexican Renaissance.

Located in the 17th century baroque building of the Government Palace in Guardalajara, Orozco’s mural dominates the main staircase. While ascending the stairs the visitor is placed in the middle of a scene from Mexican history as the mural stretches over 400 meters. Like a canopy it envelopes the concave ceiling and the perpendicular walls.

An acclaimed social realist, his work acknowledges the peasants and workers as the fountainhead of progress and power and unmasks exploiters from the religious and political hierarchy, all in the looming presence of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, the priest who spearheaded the Mexican Revolution.

Orozco’s known as a leading Fresco painter has used the challenging technique extensively. Fresco requires the pigment to be transferred to moist plaster to facilitate fusion. This not only ensures permanence but keeps the colours vibrant. The palette employed in the mural includes all possible tones and tints of black and red creating the effect of an inferno to indicate the violence and bloodshed experienced during independence. The dark recesses highlight perspective and balance the strong architectural elements within the space. Stylistically the mural echoes Constructivism which is associated with the oeuvre of the artist.

Diego Rivera (1886-1957) burst onto the headlines of US newspapers when his mural ‘Man at crossroads’, with its Communist references, won him the displeasure of his client Nelson Rockefeller and was destroyed at the RCA building at the Rockefeller Centre in New York. In his own country, despite a tumultuous relationship with the state and his intellectual peers, he won many accolades.

His large works and a series of smaller murals at the National Palace in Mexico City (1930-33) clearly refer to the Mexican folk palette and the mural conventions of the Mayan heritage. Ancient history and post independence political and social struggles are his persistent theme. At the National Palace besides a monumental work based on the Mexican Revolution that spans two floors, his over a dozen smaller murals on the cultural details of Mexican civilisations are located along the wall between doors in the verandah that skirts the courtyard on the first floor.

The people of Pakistan were introduced to monumental public murals by Sadequain (1930 -1987) whose great ceilings and wall murals are an integral part of the nation’s visual art memory. Throughout his career, Sadequain was deeply impressed by great Urdu poets like Ghalib and Iqbal who addressed the social issues of their time and shares the universal message of human freedom with his Mexican counterparts. These ideals motivated Sadequain to create murals in the public space from hospitals to airports, offices to museums and banks.

His murals (circa 1960s) in the Turbine room of the Turbela Dam eulogise the blue collar worker at a time when the industrial revolution was being heralded in Pakistan and the anticipation of the fruits of its harvest was still a romantic notion.

Sadequain completed the ceiling at Lahore Museum in 1973 and work was begun in 1986 on the ceiling at the Frere Hall in Karachi. Later it was renamed the Gallerie Sadequain. Both ceilings reference Iqbal’s message of khudi or ‘self’ as an agency of change.

The mammoth painted ceiling of the Central Gallery at the Lahore Museum takes its inspiration from Iqbal’s verse Sitaroon say agay jehan aur bhi hein, abhi ishq kay imtihan aur bhi hein (there are many worlds beyond the stars …and many challenges yet to be met), the artist puts Adam and Eve on the centre stage and challenges them to harness the untapped energy of the universe. Curled in a cocoon like embryos the male and female figures seem to anticipate the moment of awakening. The panorama that surrounds them is a tightly knit constellation of stars and planets in motion. The large discs are depicted as a kinetic mass with halos that open up in a spiral of waves. This timeless process of destruction and construction in the skies, with large meteors spewing debris in their wake to herald the birth of new planets is shown against the dense black space of infinite galaxies. This allegorical references point both to the vast resources available to man and the constraints of time put on him to complete the mandate.

The painted ceiling at Frere Hall in Karachi with its emblematic imagery expands both the pictorial and conceptual canvas. The ceiling titled ‘Al ard o was samawat’ (earth and the heavens) embrace the history of mankind and the geography of the planet. Maps of the world are depicted in several panels and long emaciated fingers holding a quill pen a reoccurring motif in Sadequain’s oeuvre, dominates the mural.

Both the size and their position in the mural of the calligraphed words ilm (knowledge) and amal (action) indicate their importance to the content. All four corners are densely populated with battalions of figures armed with tools of knowledge and progress like pens, tools of mathematicians and scientists, farming implements , even a lance with a banner of peace in Urdu and English. Mythological characters are shown as emblems of light and darkness on one side and war and peace on the other side.

Unlike most of Sadequain’s paintings and drawings which are full of angst, melancholy subjects and negation of his personal self in the tradition of the ‘fakir’ show man at his most decadent and hypocritical, his murals always reflect optimism.

Sadequain preferred to paint on wooden panels which were fixed as false ceiling, this makes his work more vulnerable and a trained restorer’ audit is long overdue. The works in the Turbine room at the Tarbela Dam may be specially threatened due to their exposure to extreme temperatures for a long period and may need re-location. The National Gallery of Art in Islamabad can come to the rescue and accommodate large works. With timely intervention, the Ministry of Culture can save a priceless work of Sadequain, the greatest muralist Pakistan has known.

Sadequain’s ‘Bahawalpur boy’

By Aziz Kurtha

I recently ventured into Karachi’s Canvas Gallery and found an unusually beguiling pastel colour painting of a young boy by the late Sadequain (1930-87) which was utterly different to anything that I had seen by him before. I knew Sadequain as an acquaintance when he visited Sharjah and Dubai in the mid-1980s. He was always charming, humble and very witty. He could never refuse scotch and often gave away fabulous works for a song or simply as thanks for a bottle of his favourite poison.

The Gallery owner Sameera Raja helpfully informed me that the painting was being sold by the (now much older) subject of the painting itself who hailed from Bhawalpur and “who was forced to sell it because of financial constraints.” Nobody could quite believe it was a genuine Sadequain. However, I sensed immediately that it was authentic. Sadequain had clearly painted the boy to look almost gamine and artificially pretty. It seemed to me that the artist was in effect idealising the boy’s appearance.

In ancient Greece and Rome it was of course the norm to sculpt and paint young boys rather than young girls. This did not automatically suggest that such artists were homosexual and Germaine Greer has stated correctly in her book The Boy — (Thames and Hudson, 2004), that “To suggest that ‘Greek artists’ were pederasts (because they painted young boys…) is as absurd as to assume that artists paint still lifes because they want to make love to shellfish and because they are hungry”.

Another related phenomenon is the ambivalent sexuality of many western contemporary artists. The flamboyant and homoerotic practices of perhaps Britain’s greatest 20th century artist, namely Francis Bacon, the celebrity effeteness of Andy Warhol, the scandalous incestuousness of the great sculptor Eric Gill, the bisexuality of Frida Kahlo and so on are only a few examples from the many.

So how to describe Sadequain’s nature and sensuality? For one thing Sadequain was extremely well read in Urdu and Persian literature with its own references to Roman and Greek classical works including the focus on young boys. Frequently in his work there are the neatly decapitated heads of male paramours with emaciated faces often resembling that of himself which indicates a certain level of narcissism. Perhaps he was recalling the story of Salome dancing for King Herod with the head of John the Baptist who was beheaded for repelling her sexual advances.

Sadequain’s own sensuality was certainly complicated and indeed tortured and there were hints of masochism as, for instance, when he observed in one of his poems: “Oh grief, my beloved took her hands off torturing me when she found I was greedy for the pleasures of pain!”

The dual phenomena of pain and ecstasy is found frequently in Christian religious texts and paintings and indeed is linked to certain aspects of martyrdom. Sadequain loved the company and adulation of beautiful women and yet his closest companions were young men. Even his camouflaged sensuality was not acceptable to strait-laced society (in Pakistan) in which he lived, but he was generally recognised as an artist of the highest calibre who added lustre to his country.

More pertinently, in looking for influences which may have contributed to the 1975 Bhawalpur boy image, it is noteworthy that Sadequain lived in Paris during the 1960s at 54 Rue de la Seine and he had participated in the Paris Bienniale in 1961 and was also awarded the ‘Laureate Bienniale de Paris’. During that time he executed a number of mildly erotic drawings with quatrain verses attached which formed the basis of the portfolio that I edited in 1999 and was translated by celebrated Indian writer Khushwant Singh.

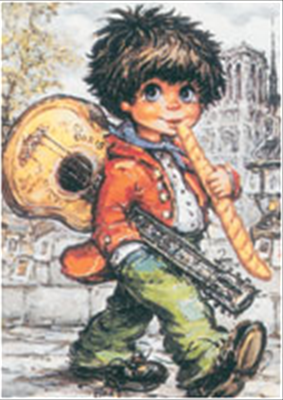

The alluring Bhawalpur boy image struck me as curiously reminiscent of some of those kitsch, rosy cheeked, gamine boy and girl postcard images which can still be bought from Paris souvenir sellers near the Pont Neuf and the Notre Dame cathedral, as reproduced here. The overly large and round eyes, the urchin mop of hair, the impish smile in those cartoon figures seem to be reflected in the fantasy image of that pretty Bhawalpur boy, who cannot realistically have looked like that.

But that is the very point, as the artist seems to be intent on idealising the boy’s image and willing upon him an unchanging identity, perhaps that of a young schoolboy in a skimpy outfit, which outlines the contours of his body.

It is clear from European art history that up till the 19th century it was often the boy who was more likely the subject of fantasies and displayed in paintings and sculpture, rather than a girl whose face and sexual features were still kept under wraps. As Germaine Greer has observed the ubiquity of male figures in ancient Greece speaks of a universal joy and pride in their visibility, a pride which the Romans had no difficulty in perpetuating through hundreds of replicas of the best known types, as with commercially reproduced nude male figures like Michelangelo’s David etc.

Only since the19th century, has it been assumed that the ideal figure that is the subject of figurative painting and sculpture, is female. However, previously great Masters had made do with boys, their own apprentices or professional models. They often drew the boys nude, and then to make madonnas of them, blurred their contours and covered them in heavy drapery.

Art and sexuality: Studying a poet’s or painter’s sexuality in relation to his art is fairly common and was attempted also, in a remarkably perceptive essay by Nobel prize winning writer J.M. Coetzee in his non fiction essays published as Inner Workings (2007). Coetzee focused on the life of the American poet Walt Whitman and noted that he wrote of the “sane and beautiful affection of man for man, latent in all young fellows”. Many writers asked whether this was a code for ‘affection’ of a more intimate kind. Similarly, Sadequain used stratagems to camouflage his preferences, for instance by painting numerous female nudes.

Nevertheless some admirers of Sadequain’s profound artistic sensibilities may legitimately consider that comparisons to kitsch images of cute boys found in souvenir shops in Paris may do him a grave injustice. However, Sadequain’s depiction of the Bhawalpur boy is couched in the fantasy of such animated pulchritude which Japanese comics (manga) aficionados call ‘super cute’ or ‘drop dead cute’. Indeed is not this cute manga culture partly traceable to the Paris urchin images and their ilk? Can it really be denied that the Bhawalpur boy’s almost caricature doe eyes and pretty urchin look, as also the pastel yellow vest, etc. are partly reminiscent of those Paris cartoon images which Sadequain must have seen?

Reciprocation of feelings: In 17th century Europe the painting of a lady was frequently undertaken at the prompting of an admirer who wished to see her portrayed looking at him and revealing her real or imaginary submission to his feelings or demands as the art critic John Berger has commented upon in his classic Ways of Seeing (1972). Isn’t Sadequain attempting something similar? Is not the idealised ‘Bhawalpur boy’ made into an involuntary accomplice of the artist imagining reciprocation of his affections?

Literary paedophilia: The popular press in the West has with zealous self righteousness created a virtual frenzy about paedophilia, which of course cannot ever be excused. And yet there are world class writers who have sometimes taken extreme positions on this issue. Thus, for instance, Nobel Laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez who, according to J.M. Coetzee, “speaks on behalf of paedophilia” in his new novella Memories of my Melancholy Whores in which on the eve of his 90th birthday a profligate bachelor decides to give himself a wild night of love with a 14-year-old virgin. On one level it is a simple story of lust but on another it is a morally complex tale in which Marquez’s argument seems to be that sensual fantasies will perpetuate, despite societal disapproval, and have done so for centuries and are indeed inherent in the human, and particularly male, condition.

Artists, including Sadequain, indulge in fantasies and idealisation which do not in any way diminish their extraordinary talents but may even enhance them. We need to live and let live those whose conduct seems to break out of the norms. It is a commonplace in art critical writing to comment that sexual energy plays some part in the creation of art and yet we need to comprehend this phenomenon at a more profound level.

If art is in essence ‘congealed energy’ then sensuality is the fount of its creativity. Lest it be mistakenly believed that this only applies to men one need only consider the words of perhaps India’s greatest modernist, namely Amrita Sher-Gil (1913-41):

“….I think all art, not excluding religious art, has come into being because of sensuality: a sensuality so great that it overflows the boundaries of the mere physical. How can one feel the beauty of a form, the intensity of a colour, the quality of a line, unless one is a sensualist of the eyes” (letter to Karl Khandalvala, 6.3.1937, reproduced for the Tate Modern solo, exhibition April 2007).

The sensualist eye of Sadequain who, coincidentally, like Amrita Sher-Gil, studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, has captured in camera shutter speed, the powerful allure of the enticing face and features of the boy from Bhawalpur. The fleeting composition by Sadequain is exquisite and yet deceptively simple, depicted in light lines, and yet some of the moral and intellectual questions it raises have existed in societies since time immemorial.