Puran/ Purân/ Puranas (scriptures)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

What are the Purans?

The truth: A Source of supreme truth

R C Kotwal,Puranas:source of supreme truth "Daily Excelsior" 25/10/2015

Purana (Sanskrit) meaning (“Belonging to ancient or older times) is the name of ancient Indian genre of Snathan dharma. They primarily are post Vedic texts containing a narrative of the history of the Universe, from creation to destruction, genealogies of the kings, heroes and demigods and description of Hindu cosmology, philosophy and geography. Purans are called the friendly treatises and are usually written in the form of stories related to one person to another. Rishi Vyasa is considered to be compiler of Puranas. An early reference to Purana in its present form can be traced to the Chandogya Upanishads in which the saga Narada refers to. Purans are estimated to 1500-2000 BC, bulks are said originated during Gupta period also. In the opinion of some scholars, they are said to narrate five subjects.

i) Sarga

The creation of the Universe.

ii) Prati- sarga

Secondary creations, mostly re-creations after dissolution.

iii) Vamsa Genealogy of gods and sages.

iv) Manvantra

Creation of Human race and first Human beings.

v) Vam sanucaritam Dynastic histories.

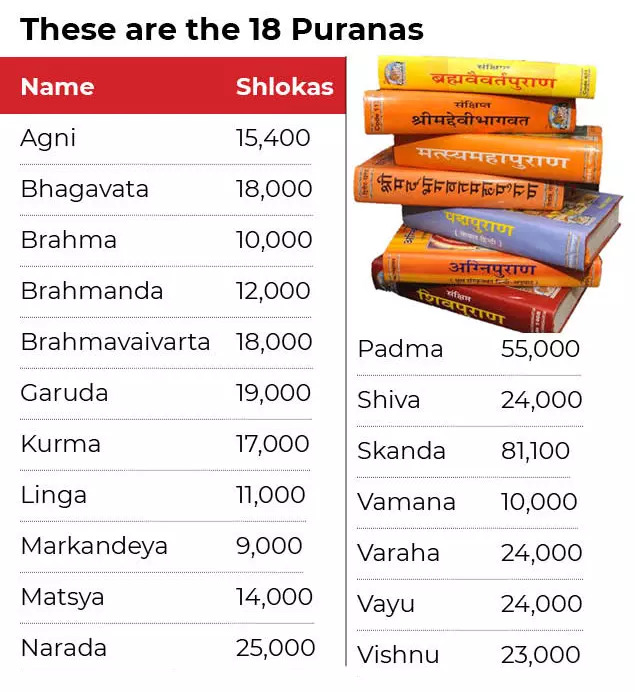

There are 18 Mahapuranas and 18 Upapuranas which are as follows.

i) Vishnu Puran (15,400 verses)

ii) Shiva Puran (24,000 verses)

iii) Naradiya Puran (25,000 Verses)

iv) Padma Puran (55,000 Verses)

v) Garuda Puran( 19,000 Verses)

vi) Varaha Puran (10,000 Verses)

vii) Bhagavata Puran (18,000 Verses) Most celebrated

viii) Matsya Puran (14,000 Verses)

ix) Kurma Puran (17,000 Verses)

x) Linga Puran( 11,000 Verses)

xi) Skanda Puran (81,000 Verses) longest

xii) Agni Puran (15,400 Verses)

xiii) Brahma vaivarta Puran (18,000 Verses)

xiv) Markandeya Puran (9,000 Verse)

xv) Bharishya Puran (14,500 Verses)

xvi) Vamana Puran (10,000 Verses)

xvii) Brahma Puran (24,000 Verses)

xviii) Brahmanda Puran (12,000 Verses)

Puranas gives lots of insights into the present day Snathan dharma or Hinduism as we call it. It is a scientific religion. Newton rested under a tree and he received the knowledge of gravity as an apple fell on his head. India knew about the Gurutvakarshan shakti (gravitational force) thousands of years before Newton discovered it. The knowledge of whole world is round was present in the ancient Khagoal Vigyan. Our ancestors had this knowledge. That’s why they kept the sun in the middle. In most ancient temples which are around 2000 yrs old, you will find the sun god in the middle looking towards the east and all the other planets are kept around it. Now-a days it is taught that Galileo discovered that the earth is round. Snathna Dharma is very close to the modern science.

The Puranas are not imaginative; they are actual histories, not only of this planet but other planets within the creation. Sage Veda Vyas due to his kindness and sympathy towards the fallen souls, supplemented the Vedas with Puranas, which easily explain the Vedic truths, intended for different types of people. The Vedas and Puranas are one and the same in purpose. They ascertain the absolute truth. Puranas are a genre of the religious literature of India. They were the scriptural basis for the development of many Hindu Sects. They developed into the popular literature about Gods and Goddesses of Samathan Dharma.

The All India Kashraj Trust, formed under Vibuti Narayan Singh, the Maharaja of Kashi, dedicated itself to publishing editions of Purans. The Purans are authoritative scriptures of Hindu Dharma. Sri Aurobindo said the Purans are of the same class as the ithiasas (the Ramayana, Mahabharata etc. they have five characteristics History, Cosmology, Creation, Genealogy of kings and Genealogy of Manvantras (the period of Manu’s rule consisting of 71 celestial Yugas or 308,448,000 yrs). All the purans belong to Suhrit-Sammitas or friendly treatises while the Vedas are called the Prabhu-Sammitas or the commanding treatises with great authority.

In Puranas, the supreme truth is made known to one and all including ordinary men, in a very simple manner. It is believed that there were approx. 64 Puranas consisting of 18 Maha-Puranas, 18 primary Upa Puranas and the rest are seconday Upa puranas.

Rishi Vyasa, the narrator of epic Mahabharata is believed to have originally compiled the Puranas. But the earliest written text dates back to the time of Gupta period around 300-350 BC. Of course this date does not in any way indicate the Puranas. But experts believe the Puranas are essentially dynamic in nature and have constantly evolved and been modified over the subsequent centuries and continue so even to date.

(The author is Superintendent of police S.K.Police Academy Udhampur, romeshkotwal3@gmail.com)

Vedic wisdom to the common man

Purans take vedic wisdom to the common man The Times of India, Jul 02 2016

Devdutt Pattanaik Hinduism can easily be divided into two phases: the vedic phase and the puranic phase. The vedic phase focussed on ritual, while the puranic phase is about narrative. The vedic phase therefore continues to be mysterious, even out of reach, while the puranic phase with its heroes and villains seems to make immediate sense. Historically, the vedic phase begins 4,000 years ago and wanes after the arrival of Gautama Buddha, 500 BCE.The puranic phase follows the rising appeal of the Buddha and his teachings, something that continues today .

The vedic phase is associated with the hymn collections or samhitas Rig, Yajur, Sama, Atharva the ritual manuals or brahmanas, and the philosophical texts known as aranyakas and more prominently, the upanishads. The puranic phase is associated with the great epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and with the chronicles known as puranas. There are many puranas: 18 major ones, hundreds of minor ones, including those restricted to a particular place (sthala-purana) or to a particular community (jati-purana). It is through the puranas, that vedic wisdom reaches the common man.

The story goes that a fisherwoman's son called Krishna Dwaipayana, whose name means `the dark one who was born on a river island', compiled and organised the vedic hymns, which is why he was given the title of Veda Vyasa.Veda Vyasa then wrote the Adi Purana full of stories that made vedic wisdom accessible.From the Adi Purana came the Ramayana, the Mahabharata and the many puranas. Thus, in traditional lore, puranas are fruits of the tree that is the vedas. fruits of the tree that is the vedas. These puranas inspired the Agama texts that replaced the old vedic yajna-shala with grand new temple complexes. The sages see puranas as an extension of the vedas: one cannot exist without the other. The Mahabharata says `Itihaas-puranabhyan vedon samupbrihayet' which means, `Study of epics and puranas supplements the understanding of vedas.' Yet modern scholars separate vedas from puranas.

Some see vedas and puranas as two distinct traditions that have nothing to do with each other, vedas being the creation of Aryans and puranas being the creation of non-Aryans, who mingled with the Aryans. They see puranas as a Hindu reaction to Buddhist monasticism, which is why the puranas and temple traditions celebrate the householder's life over the hermit's.

Others see vedas as superior and puranas as inferior, a hierarchy that was common amongst Greek aristocrats, and later colonial orientalists, who preferred philosophy over poetry and saw `logos' as superior to `mythos'. This was adopted by many Hindu `reformers' of the 19th century , who were ashamed of Hindu customs such as what they perceived as `idol' worship.

At the heart of the vedas is brahmavidya or atmajnan a deep understanding of human nature, which does not change with time (sanatan dharma).The sages struggled to communicate this idea. First they used rituals, hence the vedas. Later, with increased confidence, they used stories, hence the puranas. The former created an elite club. The latter reached out to the general public In the 21st century , we are seeing a trend towards anti-elitism and anti-intellectualism. Perhaps we need to question why some people insist that vedas are seen as different than or superior to the puranas. Why do we reject the fruit and prefer the tree? Does it indulge the ego? Does that not go against the very point of vedic wisdom?

When were the Purans written?

Bibek Debroy’s view

Bibek Debroy, January 18, 2022: The Times of India

From: Bibek Debroy, January 18, 2022: The Times of India

The word Purana means old, ancient. The Puranas are old texts, usually referred to in conjunction with Itihasa (the Ramayana and the Mahabharata). Whether Itihasa originally meant only the Mahabharata, with the Ramayana being added to that expression later, is a proposition on which there has been some discussion.

But that’s not relevant for our purposes. In the Chandogya Upanishad, there is an instance of the sage Narada approaching the sage Sanatkumara for instruction. Asked about what he already knows, Narada says he knows Itihasa and Purana, the Fifth Veda. In other words, Itihasa-Purana possessed an elevated status. This by no means implies that the word Purana, as used in these two Upanishads and other texts too, is to be understood in the sense of the word being applied to a set of texts known as the Puranas today.

The Valmiki Ramayana is believed to have been composed by Valmiki and the Mahabharata by Krishna Dvaipayana Vedavyasa. After composing the Mahabharata, Krishna Dvaipayana Vedavyasa is believed to have composed the Puranas. The use of the word composed immediately indicates that Itihasa-Purana are ‘smriti’ texts, with a human origin. They are not ‘shruti’ texts, with a divine origin. Composition does not mean these texts were rendered into writing. Instead, there was a process of oral transmission, with inevitable noise in the transmission and distribution process. Writing came much later.

How they came into existence

Pargiter’s book on the Puranas is still one of the best introductions to this corpus. To explain the composition and transmission process, one can do no better than to quote him. “The Vayu and Padma Puranas tell us how ancient genealogies, tales and ballads were preserved, namely, by the sutas, and they describe the suta’s duty… The Vayu, Brahmanda and Vishnu give an account on how the original Purana came into existence. Those three Puranas say: Krishna Dvaipayana divided the single Veda into four and arranged them, and so was called Vyasa. He entrusted them to his four disciples, one to each, namely Paila, Vaisampayana, Jaimini and Sumantu.

Then with tales, anecdotes, songs and lore that had come down from the ages, he compiled a Purana, and taught it and the Itihasa to his fifth disciple, the suta Romaharsana or Lomaharsana… After that he composed the Mahabharata. The epic itself implies that the Purana preceded it…

As explained above, the sutas had from remote times preserved the genealogies of gods, rishis and kings, and traditions and ballads about celebrated men, that is, exactly the material — tales, songs and ancient lore — out of which the Purana was constructed. Whether or not Vyasa composed the original Purana or superintended its compilation, is immaterial for the present purpose.

After the original Purana was composed, by Vyasa as is said, his disciple Romaharsana taught it to his son Ugrasravas, and Ugrasravas the sauti (narrator) appears as the reciter in some of the present Puranas; and the sutas still retained the right to recite it for their livelihood. But, as stated above, Romaharsana taught it to his six disciples, at least five of whom were brahmans.

It, thus, passed into the hands of the brahmans, and their appropriation and development of it increased in the course of time, as the Purana grew into many Puranas, as Sanskrit learning became peculiarly the province of the brahmans, and as new and frankly sectarian Puranas were composed.”

How many Puranas are there?

There are Puranas and Puranas. Some are known as Sthala Puranas, describing the greatness and sanctity of a specific geographical place. Some are known as Upa-Puranas, minor Puranas. The listing of Upa-Puranas has regional variations and there is no country-wide consensus about the list of Upa-Puranas, though it is often accepted there are 18. The Puranas we have in mind are known as Maha-Puranas, major Puranas. Henceforth, when we use the word Puranas, we mean Maha-Puranas. There is consensus that there are 18 Maha-Puranas, though it is not obvious that this number of 18 existed right from the beginning. The names are mentioned in several of these texts, including a shloka that follows the shloka cited from the Matsya Purana. Thus, the 18 Puranas are (1) Agni (15,400); (2) Bhagavata (18,000); (3) Brahma (10,000); (4) Brahmanda (12,000); (5) Brahmavaivarta (18,000); (6) Garuda (19,000); (7) Kurma (17,000); (8) Linga (11,000); (9) Markandeya (9,000); (10) Matsya (14,000); (11) Narada (25,000); (12) Padma (55,000); (13) Shiva (24,000); (14) Skanda (81,100); (15) Vamana (10,000); (16) Varaha (24,000); (17) Vayu (24,000); and (18) Vishnu (23,000).

A few additional points about this list. First, the Harivamsha is sometimes loosely described as a Purana, but strictly speaking, it is not a Purana. It is more like an addendum to the Mahabharata. Second, Bhavishya (14,500) is sometimes mentioned, with Vayu excised from the list. However, the Vayu Purana exhibits many more Purana characteristics than the Bhavishya Purana does.

There are references to a Bhavishya Purana that existed, but that may not necessarily be the Bhavishya Purana as we know it today. That’s true of some other Puranas too. Texts have been completely restructured hundreds of years later. Third, it is not just a question of Bhavishya Purana and Vayu Purana. In the lists given in some Puranas, Vayu is part of the 18, but Agni is knocked out.

In some others, Narasimha and Vayu are included, but Brahmanda and Garuda are knocked out. Fourth, when a list is given, the order also indicates some notion of priority or importance. Since that varies from text to text, our listing is simply alphabetical, according to the English alphabet. The text of the Brahma Purana has no such listing of Puranas. Indeed, the Brahma Purana is described as Adi Purana in several other Purana texts too, underlining its importance.

The numbers within brackets indicate the number of shlokas each of these Puranas has, or is believed to have. The range is from 9,000 in Markandeya to a mammoth 81,100 in Skanda. The aggregate is a colossal 409,500 shlokas. To convey a rough idea of the orders of magnitude, the Mahabharata has, or is believed to have, 100,000 shlokas.

It’s a bit difficult to convert a shloka into word counts in English, especially because Sanskrit words have a slightly different structure. However, as a very crude approximation, one shloka is roughly twenty words. Thus, 100,000 shlokas become two million words and 400,000 shlokas, four times the size of the Mahabharata, amounts to eight million words. There is a reason for using the expression ‘is believed to have’, as opposed to ‘has’. Rendering into writing is of later vintage, the initial process was one of oral transmission. In the process, many texts have been lost, or are retained in imperfect condition. This is true of texts in general and is also specifically true of Itihasa and Puranas.

The Critical Edition of the Mahabharata, mentioned earlier, no longer possesses 100,000 shlokas. Including the Harivamsha, there are around 80,000 shlokas. The Critical Edition of the Mahabharata has of course deliberately excised some shlokas. For the Puranas, there is no counterpart of Critical Editions.

However, whichever edition of the Puranas one chooses, the number of shlokas in that specific Purana will be smaller than the numbers given above. Either those many shlokas did not originally exist, or they have been lost. This is the right place to mention that a reading of the Puranas assumes a basic degree of familiarity with the Valmiki Ramayana and the Mahabharata, more the latter than the former. Without that familiarity, one will often fail to appreciate the context completely. More than passing familiarity with the Bhagavad Gita, strictly speaking a part of the Mahabharata, helps.

How they are classified

Perhaps one should mention that there are two ways these 18 Puranas are classified. The trinity has Brahma as the creator, Vishnu as the preserver and Shiva as the destroyer. Therefore, Puranas where creation themes feature prominently are identified with Brahma (Brahma, Brahmanda, Brahmavaivarta, Markandeya). Puranas where Vishnu features prominently are identified as Vaishnava Puranas (Bhagavata, Garuda, Kurma, Matysa, Narada, Padma, Vamana, Varaha, Vishnu). Puranas where Shiva features prominently are identified as Shaiva Puranas (Agni, Linga, Shiva, Skanda, Vayu).

While there is a grain of truth in this, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva are all important and all three features in every Purana. Therefore, beyond the relative superiority of Vishnu vis-à-vis Shiva, the taxonomy probably doesn’t serve much purpose. The Brahma Purana is so named because it was originally recounted by Brahma, with subsequent transmissions by Vedavyasa and Lomaharshana, Vedavyasa’s disciple.

The second classification is even more tenuous and is based on the three gunas of sattva (purity), rajas (passion) and tamas (ignorance). For example, the Uttara Khanda of the Padma Purana has a few shlokas along these lines, recited by Shiva to Parvati. With a caveat similar to the one mentioned earlier, this should be in the 236th chapter of Uttara Khanda.

According to this, the Puranas characterised by sattva are Bhagavata, Garuda, Narada, Padma, Varaha and Vishnu. Those characterised by rajas are Bhavishya, Brahma, Brahmanda, Brahmavaivarta, Markandeya and Vamana. Those characterised by tamas are Agni, Kurma, Linga, Matysa, Skanda and Shiva.

Excerpted from the introduction of The Brahma Purana Volume 1 & 2; translated by Bibek Debroy (Penguin Random House India)