PNS Ghazi

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

India Today’s account

Sandeep Unnithan, The Ghazi mystery. January 26, 2004 | India Today

With the release of pictures of the Ghazi, the submarine whose sinking tilted the 1971 war in favour of India, the debate on what caused the blast on board the Pakistani vessel is renewed.

FITTING IN THE PIECES

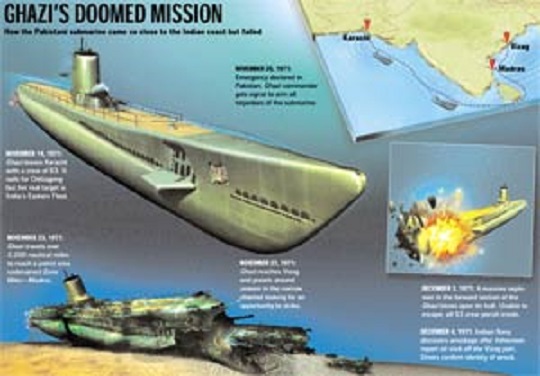

November 14, 1971: Pakistani submarine Ghazi leaves Karachi for Chittagong in East Pakistan. Its real mission is to target Indian aircraft carrier Vikrant. Fooled by an Indian ruse that Vikrant is in Vizag, Ghazi reaches the port town.

December 3, 1971: War breaks out between India and Pakistan. But a mysterious blast sinks Ghazi off Vizag harbour. Three days later, Vikrant launches airstrike against East Pakistan.

December 10, 2003: Indian Navy divers go down to examine the Ghazi in a bid to solve the decades-old puzzle. Underwater cameras take images of the vessel but the answer is still unclear.

December 4, 1971: The first rays of dawn had just illuminated Vizag harbour when Lieutenant Sridhar More steered the INS Akshay out towards the open sea.

The mystery

War had broken out between India and Pakistan the previous day, but all was quiet on the eastern coast. At least until a few hours earlier when some fishermen had visited the Eastern Naval Command with pieces of wreckage and reported an oil slick.

As the Akshay made its way to the spot, More saw an oil slick stretching out as far as the eye could see.

The first of the divers who went down to investigate surfaced after a few minutes and gasped. "Sir, it's a submarine." A second diver was sent in.

He surfaced half an hour later, excited. "I've felt the length of the submarine and its fin. The mouth is blown open." More punched out a signal to the Maritime Operations Room (MOR) in Vizag: "Have located bottomed submarine in position Dolphin light 110 4.1."

Soon after the divers could make out the Urdu initials on the black shape, More flashed his second signal. "Confirmed submarine is Pakistani." Thumbing through his copy of Jane's Fighting Ships, More sized up Pakistan's fleet of four submarines.

Three were the smaller French coastal submarines of the Daphne class, less than 200 ft long, and the fourth and largest one was the Ghazi. The divers estimated its length to be over 300 ft. More's third and last signal sent a ripple through the base: "It is the Ghazi."

December 10, 2003: Exactly 32 years and a week later, Petty Officer Rajaram Dinkar Patil rappelled down a rope into the sea off Visakhapatnam. He was part of a team of 10 divers from the Eastern Naval Command, sent down for another look at an old enemy that had come so close and failed.

As Patil switched on his underwater camera, the crew onboard the Gemini crowded around the monitor to see what he was seeing. The Ghazi, in death, was teeming with life.

Its hull was covered with thousands of fishing nets. Patil relayed what would be the first publicly released footage of the last submarine to sink in a war. Footage that experts from submarine museums in the US, USS Cod in Cleveland and USS Torsk in Baltimore, helped INDIA TODAY understand.

Ghazi was still sitting on an even keel, but its thin outer hull had all but chipped away, exposing the steel skeleton which covered its internal pressure hull and its grid of pipes and fittings. The aft escape hatch was blown open and lay exposed to the sea. An 18-inch high bronze capstan, used for docking and torpedo loading, sat fastened to the deck, chalk white and coral-encrusted.

"The fishing nets made it look like a trapped marine beast," says Commander Ajay Chauhan, command diving and special operations officer. The Ghazi had indeed fallen into and died in a net, a wartime ruse that killed it.

November 14, 1971: Millions of refugees were fleeing into India from the Pakistan Army's rampage in the east. A full-scale war seemed only a matter of time.

PNS Ghazi quietly cast its moorings and sailed out of Karachi harbour into the Arabian Sea with its crew of 93 men and crammed with food and ammunition. It had sailed out ostensibly for Chittagong in East Pakistan, but its real mission was known to only a few in the submarine directorate and probably just its captain, Zafar Muhammad Khan.

The Ghazi, formerly USS Diablo, was built during World War II. It was leased to Pakistan in 1964 and rechristened Ghazi or "holy warrior" and was South Asia's first submarine. The 26-year-old steel shark's sinews may have been ageing but it still had phenomenal Pacific reach - it could stay out at sea for 75 days at a stretch and travel over 11,000 nautical miles (17,000 km).

The pride of the Pakistan Navy now sailed to India's eastern coast to seek the aircraft carrier Vikrant in a gladiatorial contest. By November 23, the Ghazi had travelled over 2,200 nautical miles from Karachi to reach a patrol area codenamed Zone Mike - Madras.

Vice-admiral Krishnan, the Flag Officer Commanding, Eastern Naval Command, was a maverick whose colourful language could make a seasoned sailor blush. In November 1971, he looked out to sea and was a worried man.

The Eastern Fleet's aircraft carrier Vikrant was tasked with blockading East Pakistan from the sea but the vessel had a crack in its boiler which reduced its speed to just 16 knots and made it vulnerable to submarines. That was not all.

Signal intercepts of the Pakistan Navy indicated an imminent deployment of the Ghazi in the Bay. But the maverick admiral was also a master of ruses. In 1946, as the captain of the Royal Indian Navy frigate RINSShamsher, Krishnan had fabricated an alarm for a downed aircraft off Mumbai, sailed out to hunt for this "aircraft" and ensured his men didn't join the naval mutiny raging in the city.

Now, 25 years later, he had to pull off his best one yet. Krishnan did everything to let the enemy believe that the Vikrant was still in Vizag. He summoned Lt-Commander Inder Singh, the captain of INS Rajput, an ageing destroyer which was being sent to Vizag to be decommissioned.

The wily Krishnan gave it and Inder Singh one last mission - the Rajput was to pretend to be the Vikrant, sail 160 miles out of Vizag harbour and generate heavy wireless traffic - which would lead the enemy to believe there was a large ship in the vicinity. He then falsely informed naval authorities in Madras that the carrier would be arriving there shortly.

In Vizag, he began ordering huge quantities of rations - meat and vegetables - which indicated that the fleet was in harbour. He hoped that spies in the city would pick up and transmit this intelligence. The bait was snapped up.

On November 26, 1971, the Ghazi's wireless room crackled with a terse message from the commodore, submarines: "Occupy Zone Victor with all despatch. Intelligence indicates carrier in port." Khan altered course and sped his submarine north.

Zone Victor was Vizag. Reaching Vizag on November 27, the mechanical predator prowled perilously close to the Indian coast, looking for its quarry.

December 3, 1971: Shortly after midnight on December 3, an explosion tore through the forward section of the Ghazi where torpedoes and mines were stored. The shockwave blew open the knife-shaped bow, crumpling the hull and cracking open watertight compartments. Seawater rushed in, snuffing out all the lights and drowning the crew.

Ghazi's doomed mission

The submarine careened out of control and crashed to the seabed. "At a depth of 30 m, a hole as small as 0.5 mm would let in 30 tonnes of water per hour, impossible to pump out," explains marine medicine specialist Surgeon Commander Sangram Singh Pundir. "The lucky crewmen would have died in the first few seconds, the unlucky ones in the aft section hours later when the air supply ran out."

A few days later, divers blasted their way into the stricken submarine and brought to the surface six bloated bodies of Pakistani crewmen. One of the dead sailors, a Petty Officer Mechanical Engineer, had a wheel spanner tightly grasped in his fist. Another sailor had in his pocket a poignant letter written in Urdu to his fiancee.

"I don't know if you will ever read this, but we are here separated by thousands of miles of sea..." Where was the Vikrant? Days before the Ghazi arrived off Madras, the carrier and her escorts had already sailed into "X Ray" a secret palmfronded anchorage in the Andaman Islands nearly 1,000 miles away.

Here, far from prying eyes, the fleet awaited the signal to strike at East Pakistan and enforce a complete sea blockade. On December 6 morning, three days after the sinking of the Ghazi, the Vikrant launched its first airstrike. How exactly did the Ghazi die?

Official accounts of the Pakistan Navy say that it triggered off one of its own mines, but divers who studied the wreckage say the submarine must have suffered an internal explosion which blew up its mines and torpedoes. Another theory suggests an explosion of gases built up inside the submarine while its batteries were being charged.

This too has been disputed since the bodies recovered were not charred. In the past three decades, the Indian Navy has made a series of attempts to unravel the puzzle but failed. The latest expedition was another bid to solve the enigma.

"We would like to know what exactly happened to the Ghazi," says Vice-admiral (retd) Vinod Pasricha who converted the submarine Kursura and the Vikrant into maritime museums. "It would be of great historical value in the long term and would solve one of the last great mysteries of the 1971 war."

Vice-admiral (retd) G.M. Hiranandani, whose book Transition to Triumph gives an exhaustive account of the sinking of the Ghazi, says the submarine almost certainly suffered an internal explosion but its causes are debatable.

"The Pakistani account exonerates the poor condition of the submarine by saying it set off one of its mines, while the chauvinistic Indian version says the Rajput dropped depth charges sinking it." The truth about the Ghazi, which remains what the submarine community calls "on eternal patrol", lies somewhere in between.

Deccan Chronicle looks at the theories

Many theories crop up regarding the mysterious sinking of PNS Ghazi

Visakhapatnam: While there are different theories around the Ghazi’s sinking on the intervening night of December 3 and 4, the Indian Navy says that the submarine was hit and sunk by the destroyer INS Rajput. The Pakistan Navy claims an accidental internal explosion led to the sinking of the submarine.

Many old timers who were around the spot where the submarine sank said there was no activity by the Indian Navy at that time.

Mr Nannapaneni Venkateswarlu, captain of fishing vessel MT Suneeta Rani was operating off the Vizag coast at that time. “I heard a deafening sound but I was not sure what exactly happened. I am certain that there were no Indian Navy vessels around. Only once, three days before the explosion, I saw the INS Rajput passing by. Later I came to know the Pak submarine Ghazi had exploded. God saved Vizag from a Pakistani attack,” Mr Venkateswarlu said.

According to the Indian Navy, Pakistan was fed with wrong intelligence that the Ghazi’s target, the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant, was at Vizag when it was actually somewhere near the Andamans. The destroyer INS Rajput was acting as a decoy for the Vikrant. Rajput released the depth charges which blew up the Ghazi.

“The depth charge could have led to the hydraulic hammer situation on board the Ghazi and let seawater into the sub. The seawater intrusion might have led to the short circuit resulting in the explosion,” veteran submariner Cmde P. R. Franklin (Retd), who has written ‘Foxtrots of the Indian Navy’ told this correspondent.

Cmde Arun Kumar (Retd), veteran submariner and former executive officer on the nuclear submarine INS Chakra, attributed the demise of the Ghazi to a ruse of the Eastern Naval Command.

“They generated a vast amount of signal traffic on behalf of the ship (INS Vikrant) and with the command indicating that the ship was operating from Vizag whereas in fact it was doing so off Port Blair and was moved up only after the hostilities broke out,” he said.

“The Ghazi commander accordingly positioned himself outside Vizag harbour to lie in wait for the carrier to leave the harbour. Instead it met its grave there,” he said.

Cmde Kumar explained that Ships in actual hostilities while leaving harbour leave through a swept channel (of mines) and on leaving it drop depth charges routinely to deter a lurking sub. In this case it seems that during leaving harbour INS Rajput did the same and the depth charges found Ghazi sending her to the bottom.”

Mr Joseph P. Chacko, defence analyst and author of the book ‘Foxtrot to Arihant— The Story of Indian Navy’s Submarine Arm’, said, “The PNS Ghazi sinking has multiple theories. It ranges from internal explosion to accidental sinking by the Indian Navy. There are some weird ones too."

What is important is that the Ghazi sank early in the war. The plan to send the Ghazi to hoping to sink the aircraft carrier was audacious. Had it succeeded, it would have been a very demoralizing factor for the Indian Navy.

Ghazi sleeps off Visakhapatnam

The mystery of Ghazi lies embedded in the Vizag seabed, close to the harbour channel around 1.5 nautical miles from the breakwaters. The spot is marked on navigational maps for the vessels to avoid the wreck.

An attempt was made in 2003 by the Eastern Naval Command to check the condition of the debris and images of Ghazi were taken with underwater cameras. The debris lies at the 17 degrees 41 North and 83 degrees 20.6 East around 1.5 nautical miles from the harbour breakwaters.

A team of 10 divers of the Eastern Naval Command were deployed to examine the debris on Dec. 10, 2003. Ghazi’s hull was covered with thousands of fishing nets.

Vice Adm Hiranandani’s exhaustive, definitive, balanced account

Vice Adm (Retd) GM Hiranandani| 1971 War: The Sinking of the Ghazi; Indian Defence Review

Vice Adm Gulab Mohanlal Hiranandani

In his book, “Pakistan’s Crisis in Leadership”, written in 1972 soon after the war, Maj General Fazal Muqeem Khan states: (Page 153)

“The submarine GHAZI was despatched to the Visakhapatnam Naval Base in the Bay of Bengal. The GHAZI’s task was to carry out offensive mine laying against Visakhapatnam.

“GHAZI which had sailed towards Visakhapatnam with special instructions, had to reach its destination on 26 Nov 71. She was to report on arrival but no word was heard from her. Efforts were made to contact her but to no avail. The fate of the GHAZI was in jeopardy before 3 Dec. The Indians made preposterous claims about the sinking of the GHAZI. However, being loaded with mines, it seems to have met an accident on her passage and exploded. A few foreign papers at that time also reported that some flotsam had been picked up by Indian fishermen and handed over to the Indian Navy, which made up stories about its sinking”.

The Story of the Pakistan Navy’ published twenty years later in 1991, gives a slightly different account:

“The Navy ordered the submarines to slip out of harbour quietly on various dates between 14 and 22 November. They were allocated patrol areas covering the west coast of India, while GHAZI was despatched to the Bay of Bengal with the primary objective of locating the Indian aircraft carrier, INS VIKRANT, which was reported to be operating in the area.

“GHAZI’s deployment to the Bay of Bengal must be regarded as a measure taken to rectify a strategic posture that was getting increasingly out of step with military realities. Our response to Indian military deployments around East Pakistan were a series of adhoc measures, taken from time to time, as a reaction to the Indian build-up. Despatch of GHAZI to India’s eastern seaboard, not part of the original plans, was one such step taken on the insistence of our Military High Command to reinforce Eastern Command. Pressure on the Pakistan Navy to extend the sphere of its operations into the Bay of Bengal increased with the growth of Indian and Indian-inspired naval activities in and/around East Pakistan.

“The strategic soundness of the decision has never been questioned. GHAZI was the only ship which had the range and capability to undertake operations in the distant waters under control of the enemy. The presence of a lucrative target in the shape of the aircraft carrier VIKRANT, the pride of the Indian Fleet, in that area was known. The plan had all the ingredients of daring and surprise which are essential for success in a situation tilted heavily in favour of the enemy. Indeed, had the GHAZI been able to sink or even damage the Indian aircraft carrier, the shock effect alone would have been sufficient to upset Indian Naval plans. The naval situation in the Bay of Bengal would have undergone a drastic transformation, and carrier-supported military operations in the coastal areas would have been affected. So tempting were the prospects of a possible success that the mission was approved despite several factors which militated against it.

“Against it was the consideration of GHAZI’s aging machinery and equipment. It was difficult to sustain prolonged operations in a distant area, in the total absence of repair, logistic and recreational facilities in the vicinity. At this time, submarine repair facilities were totally absent at Chittagong, the only port in the east. It was on these grounds that the proposal to deploy GHAZI in the Bay of Bengal was opposed by Captain Submarines and many others. The objections were later reluctantly dropped or overruled due to the pressures mentioned earlier.

“On 14 November 1971, PNS GHAZI, under the command of Cdr Zafar Mohammad Khan, sailed out of harbour on a reconnaissance patrol. Orders had been issued to the Commanding Officer. A report expected from the submarine on 26 November was not received. Anxiety grew with every day that passed after frantic efforts to establish communications with the submarine failed to produce results. Before hostilities broke out in the West on 3 December, doubts about the fate of the submarine had already begun to agitate the minds of submariners and many others at Naval Headquarters. Several reasons could, however, be attributed to the failure of the submarine to communicate

“The first indication of GHAZI’s tragic fate came when a message by NHQ India, claiming sinking of GHAZI on the night of 3 December but issued strangely enough on 9 December, was intercepted. Both the manner of its release and the text quoted below clarified very little: “I am pleased to announce that Pakistan Navy Submarine GHAZI sunk off Visakhapatnam by our ships on 3/4 December. Dead bodies and other conclusive evidence floated to surface yesterday – 091101 EF”. Their mysterious silence for 6 days between 3 December, when the submarine was claimed to have been sunk and 9 December, when the message was released could not be easily explained. It gave rise to speculations that the submarine may well have been sunk earlier, at a time when the Indians were not ready to accept their involvement in the war. Failure of the GHAZI to communicate after 26 November strongly supported such a possibility. As it happened, the release of the message on 9 December also served to divert attention of their public from the sinking of KHUKRI on this very date even though the claim of sinking GHAZI was apparently made a few hours before the loss of KHUKRI”.

In his book ‘No Way But Surrender – An Account of the Indo Pakistan War in the Bay of Bengal 1971′, Vice Admiral N Krishnan, then Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Eastern Naval Command, states:

“The problem of VIKRANT’s security was a serious one and brought forth several headaches. By very careful appreciation of the submarine threat, by analyzing data such as endurance, distance factors, base facilities, etc we had come to the definite conclusion that the enemy was bound to deploy the submarine GHAZI against us in the Bay of Bengal with the sole aim of destroying our aircraft carrier VIKRANT. The threat from GHAZI was a considerable one. Apart from the lethal advantage at the pre-emptive stage, VIKRANT’s approximate position would become known once she commenced operating aircraft in the vicinity of the East Bengal coast. Of the four surface ships available, one had no anti-submarine detection device (sonar) and unless the other three were continually in close company with VIKRANT (within a radius of 5 to 10 miles), the carrier would be completely vulnerable to attack from the GHAZI which could take up her position surreptitiously and at leisure and await her opportunity

“We decided that in preparing our plan, we would rely much more on deception and other measures against the GHAZI.

“We had to find some place to crouch in, to spring into action at the shortest notice. After embarking the remaining aircraft of Seahawks, Alizes and Alouettes, the Fleet left Madras on Saturday 13 November for an unknown destination which I shall call “Port X-Ray,” for reasons of security. Port X-Ray was a totally uninhabited place with no means of communication with the outside world and it was well protected and in the form of a lagoon.

“Having sailed the Fleet away to safety, the major task was to deceive the enemy into thinking that the VIKRANT was where she was not and lure the GHAZI to where we could attack her. I spoke to the Naval Officer-in-Charge, Madras on the telephone and told him that VIKRANT, now off Visakhapatnam, would be arriving at Madras and would require an alongside berth, provisions and other logistic needs. Captain Duckworth thought I had gone stark raving mad that I should discuss so many operational matters over the telephone. I told him to alert contractors for rations, to speak to the Port Trust that we wanted a berth alongside for VIKRANT at Madras, etc.

“In Visakhapatnam, we ordered much more rations, especially meat and fresh vegetables, from our contractors to whom it must have been obvious that this meant the presence of the Fleet at or off Visakhapatnam. I was banking on bazaar rumours being picked up by spies and relayed to Pakistan. I had no doubt that such spies did exist and I hoped that they would do their duty.

“During the several weeks before the war, we had taken special pains to contact the various fishing communities in and around Visakhapatnam and motivate them to act as a sort of visual lookout for anything out of the ordinary that they may see when out fishing. This meant explaining to them all about oil slicks, what a submarine looks like, what sort of tell-tale evidence to look for and so on. They were briefed on exactly what to do with any information that they gathered.

“We decided to use INS RAJPUT as a decoy to try and deceive the Pakistanis into believing that VIKRANT was in or around Visakhapatnam. RAJPUT was sailed to proceed about 160 miles off Visakhapatnam. She was given a large number of signals with instructions that she should clear the same from sea. Heavy wireless traffic is one means for the enemy to suspect the whereabouts of a big ship. We intentionally breached security by making an unclassified signal in the form of a private telegram, allegedly from one of VIKRANT’s sailors, asking about the welfare of his mother “seriously ill.”

“Our deception plan worked only too well! In a secret signal which we recovered from the sunken GHAZI, Commodore Submarines in Karachi sent a signal to GHAZI on 25 November informing her that “INTELLIGENCE INDICATES CARRIER IN PORT” and that she should proceed to Visakhapatnam with all despatch!”

On the evening of 3 December, Pakistan initiated hostilities. Admiral Krishnan’s book states:

“By the time I arrived at the Maritime Operations Room, orders for commencement of hostilities had been received, the shore defences of Visakhapatnam were immediately put on alert and the Coast Battery was brought to First Degree of Readiness. I had already decided that the RAJPUT should also join the rest of the Eastern Fleet for operations off Bangladesh.

We decided that in preparing our plan, we would rely much more on deception and other measures against the GHAZI.

“I sent for Lt Cdr Inder Singh, the Commanding Officer of the RAJPUT for detailed briefing; as soon as she completed fuelling she must leave harbour. I had already ordered all navigational aids to be switched off, so greatest care in navigation was necessary. Once clear of the harbour, he must assume that an enemy submarine was in the vicinity. If our deception plan had worked, the enemy would be prowling about looking for VIKRANT. Before clearing the outer harbour, he could drop a few charges at random.

“The RAJPUT sailed before midnight of 3/4 December and, on clearing harbour, proceeded along the narrow channel. Having got clear, the Commanding Officer saw what he thought was a severe disturbance in the water, about half a mile ahead. He rightly assumed that this might be a submarine diving. He closed the spot at speed and dropped at the position two charges. It has been subsequently established that the position where the charges were dropped was so close to the position of the wreck of the GHAZI that some damage to the latter is a very high probability. The RAJPUT, on completion of her mission, proceeded on her course in order to carry out her main mission. A little later, a very loud explosion was heard by the Coast Battery who reported the same to the Maritime Operations Room. The time of this explosion was 0015 hours. The clock recovered from the GHAZI showed that it had stopped functioning at the same time. Several thousand people waiting to hear the Prime Minister’s broadcast to the nation also heard the explosion and many came out thinking that it was an earthquake.

“As per our arrangement with them, some fishermen reported oil patches and some flotsam. The Command Diving Team were rushed to the spot and commenced detailed investigations. The divers established that there was a definite submerged object some distance out seawards, at a depth of 150 feet of water and that it was a probable submarine. Even though there were a number of floating objects picked up, there was nothing to indicate the identity of the submarine. Everything had American markings. I told the Chief of the Naval Staff that personally I was convinced that we had bagged the GHAZI. He wanted “ocular proof” that it was the GHAZI, before authorizing the announcement. This was easier said than done. Diving operations were extremely difficult and highly hazardous as the sea was very choppy and the divers were operating some 150 feet below. The boat I had was not a suitable one to conduct such operations. By Sunday 5 December we were able to establish from the silhouette and other characteristics that the submarine was in fact the GHAZI. But there was no means of ingress into the submarine as all entry hatches from the conning tower aft were tightly screwed down from the inside.

“In the meantime, the Chief of Naval Staff had arranged for an Air Force aircraft to be positioned in Visakhapatnam so that “the ocular proof” that he insisted on could be flown to Delhi before the announcement was made.

“On the third day, a diver managed to open the Conning Tower hatch and one dead body was recovered. As the hatch was opened, it was clogged up with bloated dead bodies and it was quite a job to clear the same to make an entrance. The Hydrographic correction book of PNS GHAZI and one sheet of paper with the official seal of the Commanding Officer of PNS GHAZI were also recovered. The aircraft standing by finally took off for Delhi the next morning with the evidence”.

Four signals recovered from the GHAZI

The following four signals recovered from the GHAZI have been reproduced in Admiral Krishnan’s book:

FM COMSUBS TO SUBRON-5 INFO PAK NAVY DTG 221720 NOV 71

FOLLOWING AREAS OCCUPIED.

i)PAPA ONE, TOW, THREE, FOUR.>

ii) PAPA FIVE, SIX, SEVEN, EIGHT.>

iii)BRAVO ONE, TWO, THREE, FOUR, FIVE, SIX>

iv)MIKE.</li></ol>

FROM COMSUBS TO GHAZI MANGRO INFO PAK NAVY DTG 222117 NOV 71.

>FROM COMSUBS TO SUBRON-5 INFO PAK NAVY DTG 231905 NOV 71.

ASSUME PRECAUTIONARY STAGE<

FROM COMSUBS TO GHAZI INFO PAK NAVY DTG 252307/NOV 71

OCCUPY ZONE VICTOR WITH ALL DESPATCH INTELLIGENCE INDICATES CARRIERS IN PORT.

Admiral Krishnan’s book states:

“The GHAZI story, as related below is pieced together from much evidence that has been collected from the sunken submarine itself, and detailed analysis of track charts of the attacking ship, INS RAJPUT as well as that of the GHAZI. From a recovered chart, it is clearly revealed that the GHAZI sailed from Karachi on 14 November, on her marauding mission. She was 400 miles off Bombay on 16 November, off Ceylon on 19 November and entered the Bay of Bengal on 20 November. She was looking for VIKRANT off Madras on 23 November.

“From the position of the rudder of the GHAZI, the extent of damage she has suffered, and the notations on charts recovered, the situation has been assessed by naval experts as follows:

The GHAZI had evidently come up to periscope/or surface depth to establish her navigational position, an operation which was made extremely difficult by the blackout and the switching off of all navigational lights. At this point of time, she probably saw or heard a destroyer approaching her, almost on a reciprocal course. This is a frightening sight at the best of times and she obviously dived in a tremendous hurry and at the same time put her rudder hard over in order to get away to seaward. It is possible that in her desperate crash dive, her nose must have hit the shallow ground hard when she bottomed. It seems likely that a fire broke out on board for’d where, in all probability, there were mines, in addition to the torpedoes, fully armed”.

Analysis of Ghazi’s Sinking

Two points merit analysis:

When did the GHAZI sink? >

What caused the GHAZI to sink?

When did the Ghazi Sink

According to the ‘Story of the Pakistan Navy,’ GHAZI failed to make its check report from 26 November onwards.

Lt Cdr (SDG) Inder Singh was the Commanding Officer of INS RAJPUT in 1971. He recalls:

“At about 1600 hrs on 1st December 1971, I was called by the FOCINCEAST Vice Admiral Krishnan to his office. He said that a Pakistani submarine had been sighted off the Ceylon Coast a couple of days back which would be heading for Madras/Visakhapatnam. He was absolutely certain that now the submarine was expected to be anywhere between Madras and Vizag and that she was sent here to attack VIKRANT the moment hostilities were declared at a time chosen by Pakistan. Till that time, the submarine would be looking for VIKRANT and shadowing her. So the submarine would have to be prevented from locating VIKRANT at any cost before hostilities commenced.

“With this thought in mind, he wanted to hold the Pakistani submarine off Visakhapatnam till such time hostilities were declared. To achieve this, he unfolded his plan of action and said that he would like INS RAJPUT to sail out and act as decoy of VIKRANT. He wanted RAJPUT to proceed towards Madras and send some misleading signals as from VIKRANT, so that the submarine mistaking RAJPUT for VIKRANT, would be shadowing her and VIKRANT would be safe in her hiding place. FOCINC said he knew it was a suicidal mission for RAJPUT. He was sure that the Pakistani submarine would make RAJPUT a target the moment hostilities were declared and he was definite that RAJPUT would not return from this mission and that he was giving RAJPUT as a bait to Pakistan for the safety of VIKRANT. He was sorry for the move but he had no other choice. I told him that I considered myself very lucky that he had selected me for this great cause and that I was ready to take the challenge.

“On 2nd December 1971, I sailed out of harbour in the afternoon as VIKRANT and set course for Madras. I sent some telegrams through Bombay WT seeking confirmation for sickness of parent’s etc and other signals including a LOGREQ signal to NOIC Madras. It was considered necessary to increase the signal traffic as VIKRANT, being a large ship and a flagship, naturally was to have heavy signal traffic. Basic code was used for the signals. I later on came to know that NOIC Madras was baffled by the quantity of provisions and other items demanded at such short notice in my LOGREQ signal. He phoned up FOC-in-C, who showed his annoyance and asked NOIC Madras to supply whatever VIKRANT wanted.

“On 3rd December 1971, RAJPUT was asked to return to harbour, berth at fuelling jetty, top up and get ready for the next assignment. RAJPUT was secured alongside by 1900 hours. No sooner had we secured, a despatch rider came on board and informed that Pakistan had attacked Indian airfields. Before proceeding to HQENC, I left instructions to speed up fuelling, collect rations, naval stores and fresh water as required. At Command Headquarters, the Chief of Staff told me that FOCINC wanted RAJPUT to sail for Chittagong as soon as possible. I cast off from fuelling jetty at about 2340 hrs on 3rd December 1971 with a pilot on board. Scare charges were being thrown overboard whilst the ship was secured at the jetty and while leaving harbour.

“When the ship was half way in the channel, it suddenly occurred to me that “what if the Pakistan submarine which I was looking for the last two days, was waiting outside harbour and it torpedoes RAJPUT while disembarking pilot at the Outer Channel Buoy.” I immediately ordered to stop engines, and disembarked the pilot. I slowly increased speed and was doing the maximum speed I could manage by the time I reached Outer Channel Buoy.

“Shortly after clearing Outer Channel Buoy at about midnight of 3/4 December, when the Prime Minister was addressing the nation, the starboard lookout reported disturbance of water, fine on the starboard bow. As the ship was already doing maximum speed and nearing the disturbed water patch and since the ship was already closed up at action stations, appropriate depth was set on the depth charges and two depth charges were dropped at the reported position. The ship got a heavy jolt after the deafening blasts. Then the ship turned and the area was searched for any sign of a contact. Satisfied that there was no sign of any contact or anything on the surface, the ship resumed course.

“There were a few reasons which prompted me to carry out an immediate attack. First, as stated earlier, I had an intuition while leaving harbour when the ship was in mid channel. Secondly knowledge of a Pakistan submarine in the area, for which RAJPUT had been operating for the last two days to mislead her. Thirdly plain speaking by the FOCINC to me when he had called me to his office on 1st December and told me that RAJPUT mistaken as VIKRANT, would be torpedoed by the Pakistani submarine on outbreak of hostilities. And lastly the disturbed water patch made me to think that the submarine had just dived”.

Lt (TAS) (later Commodore) KP Mathew recalls:

“I clearly recall that I was on watch in the PDHQ. We were all waiting for Mrs Gandhi’s address to the nation. That was delayed by a few minutes. During that delay we received a report from the PWSS, which was located next to the Coast Battery which overlooks Vizag Outer Harbour, that there had been a very strong explosion which rattled the window panes. When they looked out, they could see a big plume of water going up quite high into the sky at a distance from them. Though the report came in very clearly, nothing much was done about it since everybody was keen to hear Mrs Gandhi. But I think it was reported by the PDHQ to the MOR that this report had come in from the PWSS”.

Cdr (E) (later Rear Admiral) GC Thadani was the Staff Officer Engineering in Headquarters Eastern Naval Command in 1971. He recalls:

“I was with the C-in-C in the MOR on the 3rd evening when CO RAJPUT was being briefed by him. As CO RAJPUT was leaving the MOR, he mentioned to me that his ship did not have wooden shores for damage control. I instantly went with him to the Shipwright Shop, gave him some shores and accompanied him to the jetty where RAJPUT was fuelling. I personally saw RAJPUT cast off. Thereafter, I went home which was on a hill which overlooked the sea. The distance from the jetty to my home was a 15 minute drive. After I reached home, whilst I was listening to All India Radio, an announcement was made that the Prime Minister’s speech had been delayed. It was during this delay period that I heard a massive explosion and the windows of my house rattled.

“The next morning at 8 o’ clock I went to the Jetty. The Commander in Chief and the Chief of Staff were talking about the GHAZI. The C-in-C went on board a boat and I went with him. We went to the site of the explosion where, I remember, Lt Sajjan Kumar was diving. He came up and told the C-in-C that he had put his hand on the ships side and felt the letters of GHAZI”.

Capt (later Commodore) KS Subra Manian, was the Indian Navy’s seniormost submariner at that time and Captain of the 8th Submarine Squadron (Capt SM in the Submarine Base at Visakhapatnam. He recalls:

“The first indication of GHAZI having sunk came in the middle of the night. A muffled but powerful explosion resembling a deep underwater explosion (distinctly different from gunfire) was heard in the naval base during the night of 3/4 Dec. The next morning (4 Dec) fishermen reported finding flotsam. It was only after this discovery that it was appreciated that possibly there had been a sinking off Visakhapatnam. The next morning (5 Dec), we went out to the spot and located the wreck. The Clearance Diving Team from Vizag was ferried across. I was there with them. They found the GHAZI sunk in fairly shallow water.

“On the day before the hostilities actually broke out, she was already in position which perhaps we didn’t anticipate. She had laid mines. One of her own may have blown her up and she sank outside Vizag harbour before she could do any further damage”.

Lt (later Lt Cdr) (Diving) Sajjan Kumar was the Officer-in-Charge Command Clearance Diving Team in 1971. He recalls:

“As far as I can remember, the explosion was in the middle of night of 3rd/4th Dec. I was fast asleep when I heard a very big explosion and my own window panes rattled loudly. I must have been dead tired because I fell asleep again. It was definitely on the 3rd/4th night that there was an explosion. I heard only one explosion, not more than one.

“On 5 December I embarked on board SDB AKSHAY with my Gemini dinghies. We were accompained by a number of catamaran type fishing boats to the site of the wreck. Before sailing, I was briefed to go and locate the object and was told that it may be a submarine.

“So we went and the team dived at the site, using the fishing boats as diving platforms. I anchored the fishing boats some distance apart and sent the divers down from the fishing boats. The first diver came up and reported that it is a submarine. The first message sent to the C-in-C was that we have located a submarine. I felt the urge to dive myself but had to postpone it to a more decisive moment because the decompression regime required we could not dive to that depth more than once in a day. After the first diver had reported that it was a submarine, I sent another better diver to find out what type of submarine it was and how big. The second diver came up and said that it was a big submarine. So a second message was then sent that it is a big submarine.

“At this stage I decided to dive myself. The visibility underwater was about 10 feet. At the depth of nearly 110 feet, the current was fairly strong, in the sense that it was not possible to swim against the current. But since a line had been snagged, we were able to reach the submarine. I first saw the silhouette from about 10 feet away. I caught hold of the various projections, the gratings, the railings and went round the entire submarine.

“Naval Headquarters had earlier provided us documents which included photos of the GHAZI from various angles, so I knew what GHAZI would look like. After I swam around and saw the various things, I came to the conclusion that this was the GHAZI and I came up. The third signal I sent to C-in-C was that it was GHAZI. After that signal was received in HQENC, they sent a message back to AKSHAY saying “Do not send any more signals.

“After about an hour, Capt Subra Manian and Admiral Krishnan came on board AKSHAY and we had a meeting. I told them what I saw about the submarine, and that there was massive damage in the portion forward of the Conning Tower”.

The submarine rescue vessel INS NISTAR undocked on the evening of 5 December. On 6 December she anchored on top of the GHAZI and commenced diving operations.

Commodore Subra Manian recalls:

“The submarine rescue vessel INS NISTAR, which had just gone into dry dock, was hastily undocked and sent out to the area on 6 Dec. The wreck was located by sonar in about 55 to 58 metres of water. After the NISTAR had moored herself over the wreck and attached a line to it, divers who went down found that the wreck had cracked open at the top forward end of the submarine, but they couldn’t get in. So they had to use plastic explosive to make an opening and enter. They then identified it as the GHAZI and recovered documents and bodies. This took about a day and probably happened on 07 Dec”.

Lieutenant (later Commander) Shafi Syed, a submariner, was embarked on board NISTAR during the diving operations on GHAZI. He recalls:

“I was instructed to embark in INS NISTAR and liaise with the Command Diving Officer to guide the divers on to the GHAZI, which had sunk off the northern side of the entrance channel to Vizag. NISTAR positioned herself on top of the GHAZI, from where we could conduct diving operations. The alignment of GHAZI, as indicated by the divers, showed that it was lying on a heading which was at 90 degrees to the entrance channel. This would be an ideal aspect from which to fire a torpedo salvo at any ship coming in or going out, which would be sunk in the channel and block it. The depth of water where she was lying was around 30 meters. She was within torpedo firing range of the harbour entrance.

“By drawing a sketch of the general construction of the submarine, I explained to the diver going down, the entry point into the conning tower. The diver reported that he had gone around the conning tower and saw that the periscope was in the raised position. He also saw a gyro pelorus, which had on top a binocular of very high magnification which could be swivelled right around. Opening the hatch the next day on 7 December, the diver entered the conning tower. He reported that there were two fully bloated bodies which were stuck in the conning tower. These were removed. Divers were then sent to recover whatever books and equipment could be brought up from the conning tower. The divers reported that there was a small plotting table in the forward end of the conning tower with some charts, GHAZI’s flag and some other flags. Most of the material which was inside the conning tower was recovered”.

Cdr (later Rear Admiral PP Sivamani) who was the Eastern Fleet’s Navigation Officer, recalls:

“A few weeks after the hostilities ended I was called to the Headquarters Eastern Naval Command one day and handed over GHAZI’s track charts, the Navigator’s Note Book and the Log recovered from GHAZI during the diving operation. I was told to analyse the track charts and submit a written report on GHAZI’s movements.

The salient points which emerged out of the analysis of these records indicated that:

GHAZI left Karachi for a post refit trial around November 1971. She came back after a day, apparently to rectify the defects found in the post refit trials. Then she left Karachi on the 14th and set course South for deployment on the East Coast. She stayed between longitude 64 East and 65 East till she passed west of Mangalore and then slowly curving in, she made a landfall fix at Minicoy. She passed close to Minicoy Island and gave a wide berth to Colombo. South of Ceylon she steered East North East and then on a northerly course fetched up off Madras PM 23 November.

At snort depth, GHAZI was doing 8 to 9 knots and maybe on surface at night it was building up to 11.5 or 12 knots. That speaks very highly of GHAZI’s performance capabilities at the time. The total distance from Karachi to Madras via Minicoy and south of Ceylon is about 2200 miles. To have traversed this distance, alternating day and night between surface and periscope or snort depth, would mean that she was averaging 10 knots. She must have been making good not less than 8 knots. Whatever be the speed made good, with the current or against the current, the fact remains that GHAZI fetched up off Madras on PM 23 November.

“Off Madras she did crossover patrols between the 23rd and the 25th. The tracks were very very clear. She had a series of fixes and she was concentrating exactly at the entrance to Madras, 10 to 15 miles either side, at a distance of 12 to 15 miles.

“She then set course for Visakhapatnam where she seems to have arrived on 27 November traversing a distance of about 340 miles. She commenced patrolling off Visakhapatnam on the 27th and did a series of crossover patrols, put out to sea eastward for a short duration, came back towards Visakhapatnam to an area 5 to 10 miles from the Entrance Channel Buoy and hung around there. The last entry made was on the midnight of 2/3 December. The chart was in fairly good condition, but the Log Book and the Navigators Note Book, written in pencil and in pen were smudged and took a little time for me to decipher.

“GHAZI’s cross over patrol off Visakhapatnam was confined to a very small area within a radius of about 2 miles centered on a position to the east of the Entrance Channel Buoy at about three to four miles. If a unit keeps on doing cross over patrols in such a small area, it will be very difficult to sift out the fixes or for that matter, translate the entries from the Navigators Note Book on to the chart and vice versa. Maybe she had put some entries or since the Navigator’s yeoman knew the submarine was in the same position, he did not keep on repeating the same position over and over again”.

The Sequence of Events.

The sequence of events after 5 Dec, when AKSHAY started diving operations, appears reasonably clear. As regards events prior to 5 Dec, there are two recollections which state that the explosion occurred on the night of 2/3 December

In his book “Surrender at Dacca – Birth of a Nation”, Lt Gen JFR Jacob, who was Chief of Staff Eastern Army Command at Calcutta states:

“We had signal intercepts of the GHAZI, a Pakistani submarine, entering the Bay of Bengal and we had passed on this information to the Indian Navy.

“On the morning of 3 December, Admiral Krishnan, Flag Officer Commanding in Chief of our Eastern Naval Command, telephoned me to say that the wreckage of a Pakistani submarine had been found by fishermen on the approaches to the Visakhapatnam port. Krishnan said that the blowing up of the GHAZI, either on 1 or 2 December whilst laying mines, was an act of God. He said it would permit the Navy greater freedom of action. Next morning on 4 December, Krishnan again telephoned asking me whether we had reported the blowing up of the GHAZI to Delhi. I said that we had not as I presumed that he had done so. Relieved, he thanked me and asked me to forget our previous conversation. The official naval version given out later was that the GHAZI had been sunk by the ships of the Eastern Fleet on 4 December”.

According to Lieutenant (later Commander) H Dhingra, who was a qualified Deep Diver serving on board the NISTAR:

“The explosion was heard a little after midnight between 1st and 2 December i.e. prior to the breaking out of war. During the night of 1/2 December itself, I received a message that an explosion had been heard and that at dawn I had to go to the jetty and report to the C-in-C. At dawn on 2 December, I, together with the C-in-C Admiral Krishnan and CO Virbahu/Captain SM8, Captain Subra Manian, we went out of Vizag harbour in the Admiral’s barge. In the barge itself I saw two life jackets which had been picked up earlier by fishermen and handed over to the Navy. We found an oil slick and a lot of flotsam. Immediately thereafter, we were told to start diving. NISTAR was floated out of dock on the 5th evening and brought to the site the next day. By that time the Command Clearance Diving Team’s divers had already gone down from AKSHAY and tied a rope on to the bollard of the sunken submarine”.

Two alternatives therefore present themselves:

A loud explosion was heard around midnight 3/4 December just before the Prime Minister’s broadcast to the nation. It was accompanied by a flash of light. The explosion rattled several window panes in buildings near the beach. The PWSS/Naval Battery reported the explosion to the PDHQ who reported it to the Maritime Operations Room. During the night, fishermen who saw the explosion picked up two lifejackets and took them to the Navy. At dawn on 4 December, the FOCINC Admiral Krishnan, the Captain SM 8, Capt Subra Manian and Lt Dhingra personally went to the site of a wreck after which clearance Divers went to the scene in a Gemini dinghy on 4 Dec. The Command Clearance Diving Team dived from the SDB INS AKSHAY on AM 5 December and identified the GHAZI. INS NISTAR started diving operations on 6 Dec. On 7 December, divers gained access into the GHAZI’s conning tower and recovered documents. On 8 December, GHAZI’s artefacts were sent to New Delhi. On 9 December, Naval Headquarters announced that the GHAZI was sunk off Visakhapatnam on night 3/4 December.

In view of Gen Jacob’s recollections about Admiral Krishnan’s phone calls on 3 and 4 December, Cdr Dhingra’s recollection that the explosion occurred on night 2/3 December and Rear Admiral Sivamani’s recollection that the last entry made on GHAZI’s track chart was on midnight 2/3 Dec, an alternative sequence of events emerges as follows:

- That GHAZI exploded at midnight on 2/3 December. Debris came to the surface, fisherman picked up and brought lifejackets to the Naval Base, which reached the C-in-C on 3 December. (On 1 December, the C-in-C was in Calcutta with General Jacob and made no mention of the GHAZI).

- At dawn on 3 December, the C-in-C, Captain Subra Manian and Lt Dhingra went to the site of the wreck in the Admiral’s barge. The C-in-C ordered diving operations to start. Clearance divers went to the site on 3 December. The C-in-C rang up General Jacob on 3 December. On the evening of 3 December war broke out.

- On 4 December, everyb

Dec 3, 2021: The Times of India

A retired naval officer recalls the day PNS Ghazi met its watery grave while chasing INS Vikrant off the coast of Vishakhpatnam

It was 1969, civil disobedience had erupted across the state of East Pakistan, that morphed into a guerilla war when ruthless killing of people by the Pakistan army resulted in the Bangladesh genocide.

I had left the Indian Navy after serving from 1949 to 1963, the last three years of which, as the first Indian chief of the flight deck of INS Vikrant, the first Indian carrier, and as per rules I was on the reservist list. Late in 1969, I was asked to report to Shiva ji for an orientation course and drafted to the Eastern Naval Command in Visakhapatnam. I reported to Commander P Mukundan, my senior. The Chief of Eastern Command was Admiral N Krishnan, my former commanding officer at INS Delhi. A couple of weeks into my engagement, the phone rang in the middle of the night. It was Commander Mukundan, his message was short: “Narasiah the balloon is up. Please report to INS Nistar at once”.

INS Nistar, was a Russian naval submarine support vessel, given on loan to the Indian Navy and was in the port dry-dock for underwater repairs. I rushed to the dry dock, and met the six Russians who were manning the vessel with some Indian sailors. I got the ship undocked in a record time of a day-and-a-half.

When we were on the job, a big thud was heard and we knew that was an unusual explosion. Admiral Krishnan from intelligence reports knew that there was an imminent threat to INS Vikrant from the Pakistan navy. A submarine on loan from the US navy to Pakistan, PNS Ghazi, was assigned to sink Vikrant and was close to Visakhapatnam. Krishnan ordered the carrier to move to the Andaman Islands. He changed the call sign of Vikrant to that of INS Rajput, an old destroyer at the base.

Uncoded messages were sent from Rajput, which appeared to be emanating from Vikrant. This made the Pakistan navy believe that Vikrant was leaving Visakhapatnam port and so ordered Ghazi to move closer, ready with its torpedoes.

Krishnan briefed Lieutenant Commander Inder Singh, the commanding officer of INS Rajput, that once clear of the harbour he can expect an enemy submarine in the vicinity.

In his book ‘No Way But Surrender – An Account of the Indo-Pakistan War in the Bay of Bengal 1971 , Krishnan writes, “Our deception plan worked only too well! In a secret signal which we recovered from the sunken Ghazi, Commodore submarines in Karachi sent a signal to Ghazi on November 25: “intelligence indicates carrier in port” and she should “proceed to Visakhapatnam with all despatch!”

INS Rajput sailed before midnight of December 3-4 and Lt Cdr Inder Singh perceived a disturbance in the water. He sailed closer and dropped two depth charges and sailed away. A little later, a loud explosion was heard and I knew that was the thud that I heard in the dry dock.

The next day, INS Nistar proceeded to the spot and the diving team established there was a submerged object at a depth of 150ft. From the flotsam American markings were visible. On the third day, a diver managed to open the conning tower hatch and a body was recovered. The report said, “As the hatch was opened, it was clogged with bloated bodies … The hydrographic correction book of PNS Ghazi and one sheet of paper with the official seal of the commanding officer of PNS Ghazi were recovered”. It was later learned that Ghazi’s own warheads had been activated by the impact of the depth charges and its nose had blown off.

I was happy to be involved, however miniscule, but a significant part, as I ensured quick undocking of Nistar. But grim news came from the western front — INS Khukri was torpedoed on December 9 by a Pakistan submarine killing 18 officers and 176 sailors and its captain Mahendra Singh Mulla went down with the ship. Commander Oomen, chief engineer and a senior of mine from Shiva ji, too went down.. Such are the bittersweet memories of that time.

( As told to Arpita Bose. K R A Narasiah is is an ex-servicemen of the Indian Navy)

See also

1965 War: The role of the Indian Navy