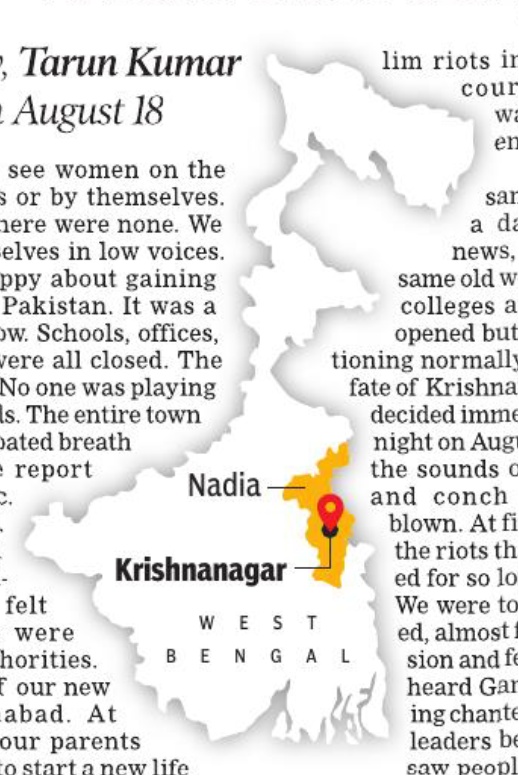

Krishnanagar

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Why Krishnanagar celebrates I-Day on August 18

August 14, 2022: The Times of India

From: August 14, 2022: The Times of India

When we woke up on August 14, the first thing I thought was that the next day we would be citizens of a nation that was independent of British rule. Even if that independence would push us towards Pakistan, I would be able to breathe the air of a free country. I was cognizant of the fact that this was coming after many decades of political movements — armed and peaceful — and what separated us from freedom was just one night. And yet, for all my excitement and happiness, the worry of which side of the border we would end up in remained heavy in our minds. If Krishnanagar was to become a permanent part of East Pakistan after the division, then there were many question marks hanging over our future. At midnight, I stood in front of a radio shop. There was a huge crowd. We stood there, all of us, and heard Nehru speak the now famous words — our tryst with destiny — and that’s how I knew that power had changed hands, and we were citizens of the new nation of East Pakistan. Nobody felt happy about this. In the crowd, there was a significant number of Muslims, and they didn’t look happy either. No firecrackers were burst. The next day, the sun rose in an independent Pakistan. The Pakistan flag was supposed to be raised in the town hall grounds, and I knew I had to go there because I used to hang out with senior members of the Congress in their office and was seen as a ‘Congressi type’. I did not want to be considered as part of the ‘enemy’ camp, so to speak, now that we were in Pakistan. So, I went there. On the ground, we saw that the Congress president hoisted the flag. Standing behind him were Naseeruddin, the DM, the police superintendent, the newly promoted DIG of East Pakistan and Shamshud Doha, who was notorious for his role in the Calcutta riots the year before. The Muslim League MLA was also there, of course. The flag was hoisted, the Congress leader expressed his commitment to the new nation, and we all shouted slogans of ‘Pakistan Zindabad’ and ‘Quaid-e-Azam Zindabad’. Then the ceremony ended.

Krishnanagar felt like a ghost town. Previously, in the relatively liberal environment of Krishnanagar, it was a familiar sight to see women on the streets, in groups or by themselves. But on this day, there were none. We too talked to ourselves in low voices. We didn’t feel happy about gaining independence in Pakistan. It was a day spent in sorrow. Schools, offices, colleges, courts were all closed. The cinema was shut. No one was playing football in the fields. The entire town was waiting with bated breath for the Radcliffe report to be made public. We felt cornered. We were worried about the animosity the Muslims felt towards us. We were scared of the authorities. We were scared of our new rulers in Islamabad. At home, we heard our parents worry about how to start a new life in a new place.

If Krishnanagar was to become a permanent part of East Pakistan, then there would have to be some major changes in the household, and I knew my parents were worried about that. August 16 was spent in the same way. But we read some news from Calcutta that gave us some strength. There were some stories of Hindu-Muslim harmony in Calcutta from August 14. There were small processions of each community that travelled to meet the other and gave them garlands, fed them sweets and initiated hope for a new era of communal harmony. Nobody could imagine that such a thing would happen. And these were just ordinary people. Without caring a hoot about political leaders, they managed to stem the tide of year-long Hindu-Mus- lim riots in Calcutta. Of course, Gandhiji was a great influence behind this. It was the same the next day: a day of no real news, a day with the same old worries. Schools, colleges and offices had opened but were not functioning normally. We hoped the fate of Krishnanagar would be decided immediately. At midnight on August 18, we heard the sounds of firecrackers and conch shells being blown. At first, we thought the riots that were thwarted for so long had started. We were totally disoriented, almost frozen in confusion and fear. But then we heard Gandhi’s name being chanted and Congress leaders being hailed. We saw people were smiling and coming out on the streets, and that’s when we realised that Krishnanagar was going to remain a part of India. All the Pakistani flags were brought down. Those who had raised them were the same people who brought them down. The DM, Naseeruddin, transferred the responsibility to the new magistrate — a Hindu — and left for his new workplace, Kushtia, which had become a part of East Pakistan. Strangers and friends were greeting each other with chants of ‘Jai Hind’. It may have been midnight, but the streets were filled with people. Everyone was overwhelmed with emotion by the news. Roy was born in 1929. He now lives in Kolkata. His story is excerpted from ‘Independence Day: A People’s History’ by Veena Venugopal published by Juggernaut