Shama Futehally

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Shama Futehally

March 25, 2007

REVIEWS: Translated lives

Reviewed by Samina Choonara

THERE can be several reasons to appreciate Shama Futehally’s posthumously published novels, short stories and literary essays, none of which have to do with the desire to read elegant prose. She can be read, for instance, as postcolonial Indian literature, feminist fiction, or indeed as an English-speaking representative of the ’50s progressive writers in united India.

It is not as though Futehally writes poorly; her homely fiction choreographs women’s anxious lives around the public careers of their men, her language sparse and modest like a good Nehruvian housewife. No delicious sensuality of place or ambiguity of emotion, no presence of the female body in ever disputed public spaces or even existentialist angst, because her women do not seem to experience themselves as individuals with a canker in the heart.

Futehally’s novels read well and carry a general sense of wellbeing, a bit like a home-knit sweater — comfortable, chunky, obviously made with love and smelling of a log fire and some nuts eaten alongside it — ultimately embarrassing precisely for these reasons.

To experience the sophistication of Shama Futehally’s mind, it may be best to go straight to her collection of essays published in an anthology titled, The Right Words. Here, in conference papers, classroom lectures, and newspaper articles, the writer documents her life as a translator, writer, and teacher of the English language. She confronts the problem of how to make peace with an imperialist language that remains tainted by class disparity as the language of the privileged in India (and, by extension, in Pakistan). And yet, after 300 years of the British rule in India, we live transcultural, translated lives where the English language and its imaginary are alive in the way we conceive our world. So how does an Indian write fiction or poetry, or indeed translate from one language into another, without sounding false and without invoking class privilege?

Futehally looks for these answers in many places. She revisits the fictionalised characters of Anita Desai who speak an English of artificial fluency and correctness, or those of Ruth Jhabvala who speak satirically incorrect English, “the first approach reduces the credibility of the a character, the second reduces his appeal”, she writes. It is the characters of Salman Rushdie who use English “… totally wrong, completely acceptable, capable of transmitting extremes of human experience”. Futehally accepts that there is no ready stock of English or Indian idiom that this new language can draw upon but, like poetry, something quite individual, a khichri of Indian English that has to be created. She thinks that it was perhaps the unabashed, somewhat jocular Indian English of Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children that was one of the reasons for the novel’s phenomenal success.

Futehally comments on all the variant forms of English spoken in India (read South Asia), the use of the continuous “I am not understanding what you mean”, or the distinctly Indian collocations “to feel a difficulty”, tautologies such as “I’ll return back” and, of course, literal translations from the vernacular that actually sound quite interesting like “stop eating my head” or “he talks in the middle”, etc. Then there is the familiar interrogative inversion like “where you are going?” and so on, the completely changed usage of words like “mood” (shaadi karne ka mood nahin hai) where it stands for a semi-permanent state of mind or “bore” (bahut bore ho gaya) which can express a feeling of frustration or irritation.

How does an Indian write fiction or poetry, or indeed translate from one language into another, without sounding false and without invoking class privilege?

Here Futehally states, “What I find distressing about Indian English is not that it is not correct, but that it is not self confident”. She feels that only through owning this new variant of English and using it unpretentiously can this language come home. It may well be that Indians and other non-White postcolonials are far too busy in trying to sound right, which is to say, sound British. This, says Futehally, not only makes for bad politics but for poor Indian fiction in English.

Then there is the issue of translation, whether it is English classical texts being translated into the vernacular or the other way around. Futehally thinks the reasons behind any translation need to be questioned, for it is often cultural contexts that are lost in translation. For instance, she makes a study of the many controversial translations of Rabindranath Tagore that falter because Bengali contains the assumption that lyricism is a valid way of looking at the world whereas “Modern English contains the opposite assumption, implied in its tone, pace and vocabulary — the assumption that an intelligent view of anything can hardly be other than detached and ironical.” This is one reason why Tagore in translation generally sounds sentimental and “syrupy”.

But translations can fail for several reasons. For instance, English translations of the Urdu ghazal or nazm fail, especially in the case of Ghalib, because here sound and meaning live off each other, and “a group of words has power and wit only when spoken to a certain intonation”, according to Futehally.

Yet another reason for the failures of translation applies to the rendering into English of Bhakti poetry which carries a complexity of emotion — being tender, serene, and despairing at the same time — devotional poetry that appears to be written by agnostics. Futehally has attempted at translating some works of Mirabai not because she could not find satisfactory versions in English, but because she needed to interpret the song in her own way.

Here, the writer acknowledges that the issue is not one of fidelity to the original because, just like in a good relationship, fidelity may be an insufficient reason for the success or failure of translation. What is needed is for translation to be an experiential act carried out with great engagement with and some respect for the realm of the other.

To continue with the theme of translation, Futehally’s novels and short stories do not seem to work except as translations into English of the works of fifties’ radicals: the Progressive Writers’ Movement. A number of stories — her short stories collected here in Frontiers — speak of middle-class guilt regarding the poor who surround their lives. The sins of the progressive writers thus visit Futehally where, in an attempt to appear unsentimental, “modern”, and descriptive, the writing becomes too mannered and sterile. Short story writing is not the medium that works best for Futehally, and her stories read more like exercises in how to write a novel, an apprenticeship, in a manner of speaking, where characters are studied and cameo situations are described.

Her novels are more competent though, and in Tara Lane, her first novel set in ’50s India, which is often considered autobiographical, she details the collapse in the fortunes of a mercantile family because of labour trouble in the factory. The novel is brave in that it documents the emotional frailties of women used to a life of calm luxury provided by their rich husbands, but Futehally does not go far enough in critiquing it as an exploitative or self-serving position that pushes the men of the household towards moral decrepitude.

Reaching Bombay Central is perhaps Futehally’s best work in terms of its fluidity and the complexity of emotion it addresses. Again, the narrative focus is an anxious, middle-aged woman travelling up to the big city by train.

Shama Futehally is too polite and too much a product of Nehruvian India to articulate the reasons behind the decline in fortune of her central characters. She will but only clear her throat, as it were, and hum and haw instead of saying that the problems stem from being Muslim in India. Like a true fifties’ radical, she probably considers it beneath her to refer to the ethnic, linguistic or religious origins of people that may be invoked for discriminatory purposes, but will only focus on class difference as the single defining category of oppression.

This was once considered the strength of Leftist politics that it did not trap people in originary myths of ethnic or linguistic belonging but attempted to form broader alliances around social issues, a strength reflected in the literature produced by the progressive writers of the ’50s — people like Ismat Chughtai, Rashid Jahan, Khadija Mastur and Amrita Pritam, to name just a few women prose writers among them. Unfortunately, in our troubled times, such delicate emotion sounds disingenuous, only because Futehally’s India has ceased to exist, if it ever actually did.

The Right Words ISBN 0-14-306218-2

Tara Lane ISBN 0-14-306219-0 174pp. Rs195

Reaching Bombay Central ISBN 0-14-31009-1 154pp. Rs195

Frontiers ISBN-14-306217-4 203pp. Rs250 By Shama Futehally Penguin Books www.penguinbooksindia.com

A brief backgrounder

From: Twitter

From: Twitter

Rumour has it there once was an Urdu magazine so popular that it was smuggled across the border and sold for exorbitant prices. Hard to believe? Trace Shama’s journey with us in this thread.

In the early 20th century, there was a surge and disruption in the way Urdu was used.From being a language of Tehezeeb it started becoming a language of rebellion.When the words of Rashid Jahan and Sajjad Zaheer sparked flame and anger,Urdu discourse would forever be changed.

Others wanted to make Urdu heard in a different way. With the coming of the Talkies, early 20th century Cinema in India was gaining new ground. With that came the opportunity for a new kind of discourse.

The advent of film journalism in undivided India probably started in Lahore where ‘Cinema and Chitra’, published in the late 1920s, was the first to make some real dent in this new field of journalism. The language of communication was primarily Urdu.

Urdu was and still is deeply intertwined with the Hindustani-speaking parts of the country, and it was from around the areas of Lucknow, Lahore, and Delhi, where people went into the glittering film industry to make a mark.

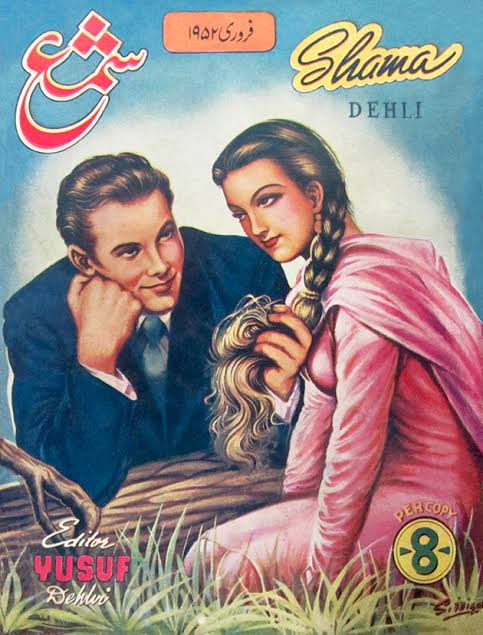

It’s not surprising that Urdu as a language became a mainstay in the early rising days of the Film industry. Shama began publication in 1939 with Yusuf Dehlvi, a successful Delhi businessman who had dealings in real estate and leather, as its proprietor.

Shama was conceived as a combination of religious and literary magazines. What made it stand out was its ability to combine and present its hybrid nature in an articulate & acceptable manner without delving into cheap slander.

Priced at two annas a copy, the first issue had this couplet on its cover:

Lo shama hui raushan, aane lage parwaane,

Aaghaaz jab aisa hai, anjaam khuda jaane (Behold the candle is burning, the moths are coming

When the beginning is like this, God knows how it will end)

It didn’t receive instant popularity and Yusuf and his family had to really dig deep. However, the heavy usage of Urdu in the industry was a big help. Urdu Poetry was used in the form of song lyrics and many Urdu novels and plays were even used as film screenplays.

Many of these writers who regularly contributed their poems and short stories on Shama were also involved heavily with the film industry, working on dialogues and screenplays. As the motion pictures started gaining popularity, so did Shama.

The era of Urdu Magazines had only begun. Partition led to a sizable influx of Urdu readers in India and for them, Shama became an addiction. But Shama didn’t just lie on their laurels. Their contributors were some of the best and most well paid names in the industry.

Among their contributors were writers like Rajinder Singh Bedi, Ismat Chughtai, and Krishan Chander, and celebrated poets like Jigar Moradabadi and Firaq Gorakhpuri. Regular film columnists included award-winning names such as K.A Abbas and Rahi Masoom Raza.

By the 1950s, almost the entirety of the Delhvi clan, including Yusuf’s three sons, Younus, Idrees, and Ilyas, and some of their wives, was in the business. Shama's commercial success even led to spin-off publications.

There was Bāno (Lady), a magazine specifically for women, Khilaunā (Toy) for children, the crime/spy magazine Mujrim (Criminal), and others, all under the Shama Umbrella. Yusuf hadn’t only created a successful business but also a nuanced space for articulate discussion.

Though the records haven’t survived the tides of time, Shama was supposedly the first monthly Indian journal of any kind in any language to surpass the 100,000 subscribers milestone as early as the 1950s, selling almost 1.5 lakh copies a month.

Such was its popularity that it was ferried across the border in large numbers. Custom officers would often ask, “Is there anyone who is not carrying Shama?” It had become a commodity that people wouldn’t think twice about spending a lumpsum on.

What added to the craze was the Adabi Muamma, monthly crosswords puzzles, which carried a hefty prize money for the winners. It even got a mention in the Shabana Azmi Starer Anjuman, released in 1986, which was considered a rare distinction for a film magazine.

Shama was loved by the stars. Dharmendra was once heard saying, “I’ve been diligently reading Shama since the time I was studying in the 9th…can say this without any hesitation that my desire to get into films was kindled by Shama”.

The likes of Raj Kapoor, and Waheeda Rehman would often visit the Shama Kothi (Delhvi House), as did the likes of Meena Kumari, Nimmi, and Jayant. There was even a rumor that it was Yusuf Dehlvi who persuaded Sunil Dutt to allow Nargis to act in Raat Aur Din.

The 1990s may have been a boom for many, but for Shama and its many contemporaries, it was twilight. The Shama office closed down in 1999, bowing down after almost 6 decades of relentless pursuit of literary eminence.

Given the kind of vitriol the language receives today, it’s hard to imagine that not so long ago an Urdu Magazine was mainstream and popular. How it wowed its readers for all those years without ever letting its standards down is something we can learn from even today.

Sources: The Golden Age by Yasir Abbasi - (https://indianquarterly.com); The Filmī-ʿIlmī Formula: Shama Magazine and the Urdu Cosmopolis by Afroz Taj - Journal of urdu studies (http://brill.com/urds); Yeh Un Dinoñ Ki Baat Hai: Urdu Memoirs of Cinema Legends by Yasir Abbasi;