Union budget: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A backgrounder

Written by Udit Misra, January 31, 2023: The Indian Express

An Annual Financial Statement

The Union Budget is more technically called the Annual Financial Statement. It is true that the budget has traditionally been seen as the most influential tool in the hands of any government to signal its choice of policies, but at the heart of the exercise lies some basic accounting.

Any budget essentially provides three big details.

One, the total amount of money that the government will raise in the coming year; this is called the total receipts.

Two, the total amount of money it will spend; this is called the total expenditure.

Three, the total amount of money it will borrow from the market to plug the gap between what it spends and what it earns; this is referred to as the fiscal deficit.

Forces that shape a Budget

Let’s start with something that is dominating the news flow at the moment. Notwithstanding considerable secrecy around budget-making, newspapers are full of stories about what to expect from the Union Budget.

Essentially, all demands can be placed in three different categories.

One set of demands, essentially, is for a lower rate of taxation and/or a higher rate of exemptions. In other words, people and firms lobby to get their tax burden reduced.

For instance, salaried taxpayers may be demanding that income tax exemption levels — that is, the annual income level which escapes any taxation — should be raised. That’s because over the past few years, inflation has been high, and as such, even if someone’s salary went up by, say, Rs 1 lakh annually, that additional money might largely be going into paying higher prices. In other words, Rs 4 lakh per annum salary today may have the same purchasing power that a salary of Rs 3 lakh per annum had 2-3 years ago. As such, an argument can be made that the government should raise the income tax exemption limit from Rs 3 lakh to Rs 4 lakh. That is to say that no income tax will be charged if your annual income is Rs 4 lakhs.

To be sure, the numbers used in this example are just for illustrating a point.

The second set of demands is from people/firms wanting higher or newer subsidies. An example could be a firm that produces green energy or produces products that run on cleaner fuels. Such a firm/entrepreneur may argue that subsidising (or increasing existing subsidies) will help India transition to a cleaner environment in the coming years. There might also be sectors — such as travel and tourism — that have been most severely hit by the pandemic (and have struggled to recover adequately) and want some special help from the government.

The supporting argument in both types of demands is the same: In the absence of lower taxes or higher subsidies, such people/firms/sectors will struggle to grow, thus dragging down the overall growth of the economy. These demands are made not from the perspective of the Union Budget but from the demands of their individual budgets.

There is a third category of demands. It is a small group but it is influential. This group demands something called “fiscal rectitude or prudence”. Simply put, they demand the exact opposite of the first two categories. They demand that the government cuts down on its fiscal deficit (essentially the total amount of money the government borrows from the market in order to bridge the gap between its total expenditure and its total receipts). More often than not, cutting down the deficit, in turn, requires the government to maximise revenues and prune subsidies.

The final details of the Union Budget are the compromise solution between the pulls and pressures of these three demands.

Scope of the Union Budget

On the face of it, the Union Budget appears to be the single biggest economic news event in any year. Before the Budget it might appear that all the problems of India’s economy can be solved by the Union Budget. [To be sure, when one refers to the Union Budget in this context one refers to the total expenditure pencilled in by the Union government.]

It is expected that as the size of the Union Budget increases, the higher government expenditure will push the economy forward. But there are two reasons why such expectations should be tempered.

One, there was a time in India’s history when the Union Budget was the biggest game in town. In other words, the total budgeted expenditure of the Union government was not only much more than the budgeted expenditure of any one state but also significantly more than the total budgeted expenditure of all states put together. In those days, the Union Budget was the prime mover of the Indian economy.

But over the years, this has changed. Nowadays, the size of the Union Budget is smaller than the combined budgets of all the state governments. For instance, in the current financial year (2022-23), the Union government is expected to spend Rs 39.5 lakh crore while all the states put together are expected to spend Rs 47.6 lakh crore. This means states will spend 20% more than the Centre in FY23.

With states spending more, the ability of the Union Budget to influence the economy is coming down even though the Union Budget remains the single biggest budget of the year.

Two, while on the face of it, the Union government spends something like Rs 40 lakh crore, not all this expenditure is completely new. In fact, as Pronab Sen, former Chief Statistician of India, recently said in a conference (organised by the International Growth Centre), year on year, the Finance Minister has just about 7% of the total budget at her disposal for fresh allocation. The first 93% goes into expenditures that are already committed — think of all the ministries and all the schemes that are already in play. So the FM doesn’t exactly have Rs 40 lakh crore to allocate; rather just about 7% of it for new allocations.

These two factors provide a context for what to expect from any given Union Budget.

Preparation of a Union Budget: Key steps

Before the Union government can decide on its revenue and expenditure plans it needs to know how the overall economy would do in the coming year. That’s because its revenues will depend on the size of the overall economy and its growth rate. To arrive at that number, the government has to first figure out what is the likely size of the economy in the current financial year (April to March); it is noteworthy that at the time of the Budget presentation, the current financial year would still not have ended.

1: Nominal GDP (or what will the size of the economy be next year?)

So the starting point of next year’s Union Budget is to ascertain the “nominal” GDP of the current year. Nominal GDP is nothing but the total market value of all the goods and services produced in India in a financial year. For purposes of analysing the economy one often uses the “real” GDP but for preparing the budget, it is the nominal GDP that matters. The real GDP is “derived” from the nominal GDP by removing the effect of inflation. Prof N R Bhanumurthy, vice chancellor of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar School of Economics (BASE) University, refers to nominal GDP as “Lord Ganesha” of budget making.

Once the government knows the nominal GDP of the current financial year, it uses this number to project the likely nominal GDP in the next financial year (in this case, 2023-24) for which the budget is being made.

The “Budget At a Glance” document in the Union Budget clearly mentions this projection. For instance, last year’s Union Budget stated the following: “GDP for BE 2022-2023 has been projected at Rs 2,58,00,000 crore assuming 11.1% growth over the estimated GDP of Rs 2,32,14,703 crore for 2021-2022.”

2: Fiscal Deficit (or how much money can the government borrow?)

Typically in India, as indeed is the case with most developing economies, the governments are forced to spend more than they earn. That means they have to borrow money from the market. But overtime India instituted strict rules limiting how much the Union government can borrow. These limits are set by the Fiscal responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act. The FRBM Act stipulates that the total borrowings (fiscal deficit) cannot be more than 3% of the (nominal) GDP.

So once the government has arrived at an estimate of the nominal GDP it then calculates the total amount of money it can raise from borrowings. At present, the fiscal deficit is much higher than 3%, thanks to the additional spending (for example, additional food subsidy to the poor) the government has had to do in the wake of the pandemic.

3: Total Revenues (or how much money can the government raise on its own?)

Once the government knows the maximum money it can raise from borrowings, it trains its attention towards its revenues. The challenge now is to figure out how much money can be raised through various means. There are three main ways to raise revenues — tax revenues (by levying taxes), non-tax revenues (such as the dividends earned by government-owned enterprises etc.), and money raised through disinvestment of public sector undertakings.

4: Total Expenditure (or what is the maximum it can spend and where?)

By now the government knows both how much money it can raise on its own and how much money it can borrow. Taken together, they provide it with the total money it can spend on different schemes — old or new. The next step is to apportion this money among different ministries and departments. That completes the budget-making process.

Budgets that signalled a change

1947

From: February 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The union budget of 1947, which made a difference

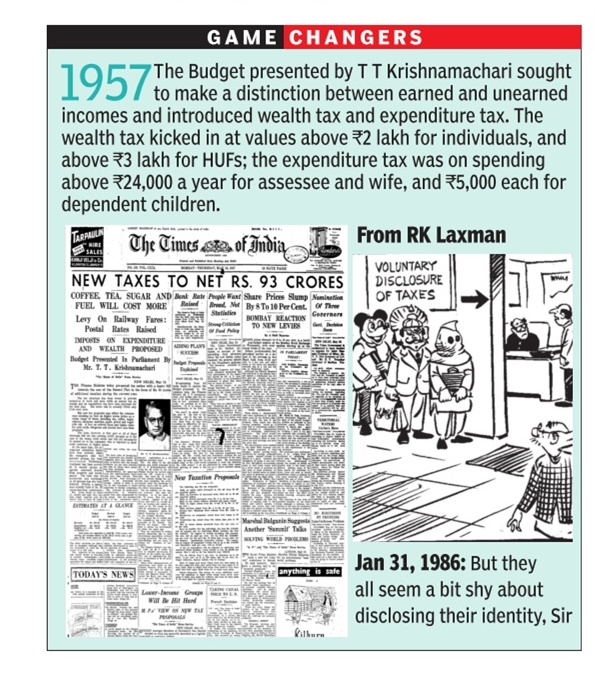

1957

From: February 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The union budget of 1957, which made a difference

1970

From: February 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The union budget of 1970, which made a difference

1991

From: February 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The union budget of 1991, which made a difference

1997

From: Feb 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The union budget of 1997, which made a difference

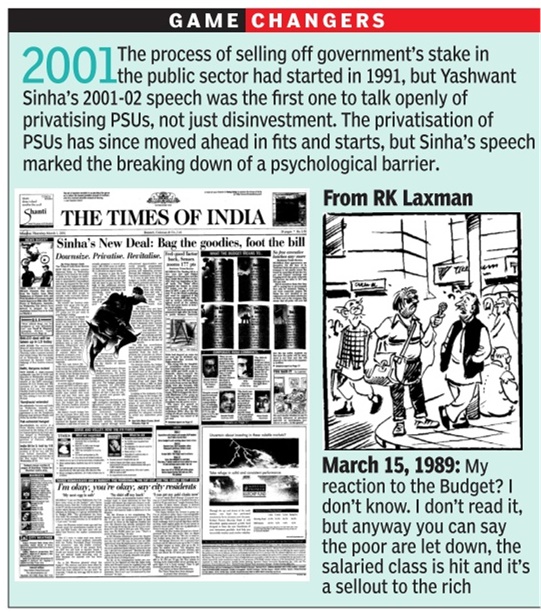

2001

From: February 2, 2022: The Times of India

See graphic:

The union budget of 2001, which made a difference

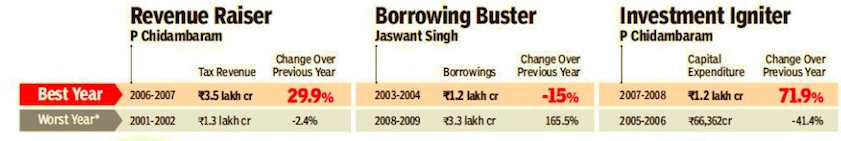

1990-2009

February 2, 2018: The Times of India

From: February 2, 2018: The Times of India

From: February 2, 2018: The Times of India

Finance minister Manmohan Singh’s 1991 Budget is widely regarded as India’s best, but as an annual financial statement of the government, it wasn’t remarkable. It would be facile to categorise a Budget in terms of best or worst because, just as Budgets affect the economy, they are also impacted by the economic and political environment of the time, which may not be within a finance minister’s control. Besides, governments often take big decisions outside of the Budget — for example, the 1991 devaluation of the rupee or the 2017 GST rollout. In picking five out-of-ordinary Budgets here, we focused only on their role as financial statements and not as instruments of policy-making. Only Budgets between 1990-91 and 2015-16 were considered because the structure of the economy has changed since the 1990s and actual data for 2016-17 isn’t available

Vignettes

B

[ The Times of India]

From: The Times of India

Every year, the finance minister would treat ministry officials to halwa as part of a ritual before the Budget papers went for printing. While the Budget has gone paperless, instead of the halwa ceremony [in 2022], sweets were shared around with the staff

Before Nirmala Sitharaman, FMs brought the Budget to Parliament in a brown leather briefcase. She broke the tradition first with a red cloth bag that she termed “bahi khata”, and then with a made-in-India iPad

Nirmala Sitharaman’s 2-hour-40minute Budget speech in 2020 – cut

short because she felt unwell – was the longest ever. The shortest was HM Patel’s 800-word speech in the 1997 interim Budget

Budget transparency

2013-14

The Times of India, Sep 10 2015

India's budget transparency score worse than Bangladesh's

NZ tops list, China lowest among BRICS

An international report on budget transparen cy places India at a middling level globally and next only to Bangladesh in South Asia. The report, which looks at 2013-14, the last year of the UPA, gave India a score of 46 on 100, just slightly better than the average of 45 for all the countries surveyed.

The report, Open Budget Survey 2015, brought out by the International Budget Partnership, evaluates countries on the transparency of their budgeting process on several counts under three major heads public participation, oversight by the legislature and oversight by audit. India scores an impressive 75 on 100 in oversight by audit, but performs poorly on the other two counts. In particular, on public participation, India's score was a mere 19 on 100.

On top of the list was New Zealand with a score of 88.Sweden, South Africa, Norway and the US all scored in the eighties. Among the BRICS nations, apart from South Africa, Brazil with 77 and Russia with 73 had scores well above India's, but China with a score of just 14 was judged to have among the least transparent budget processes.

India's score is a significant dip from the 62 it scored in an earlier round of the same survey in 2012. However, the sharp drop is largely on account of temporary factors like the mid-year review and the year-end report not being presented in time.

These delays could be attributed to changes in personnel (like Raghuram Rajan moving from the chief economic advisor's job to head the RBI and his replacement taking time), which is why they are seen as a temporary regression.

The report does make the point, though, that while the regressions may be temporary and the rebound from them quick, they highlight what can happen “when the mechanics of publishing documents on time are not sufficiently institutionalized“.

Had India retained its score of 62 it would have been among the better countries globally and comfortably led in South Asia.

The research for the survey was done by 102 research and civil society organisations working around the world. The organisation doing the research for India was the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA), an NGO advocating greater transparency and accountability in budget making in India.

2017: India above global average

India beats global average on budget transparency, February 1, 2018: The Times of India

From: India beats global average on budget transparency, February 1, 2018: The Times of India

Ranks 53 Out Of 115 Countries In Survey

India has scored slightly better than the global average when it comes to budget transparency, according to results of the Open Budget Survey (2017) released on January 30. With a rank of 53 among 115 countries covered by the survey, India’s score of 48 out of 100 for transparency (as against the global average of 43) showed an improvement of 2 percentage points over the 2015 index.

Every two years, the International Budget Partnership (IBP) — using over a hundred indicators — assesses budget transparency based on the amount, level of detail and timeliness of budget information made available to the public. Results of the Open Budget Survey (2017) highlight that the global average score of budget transparency has declined by 2 percentage points from 45 in 2015 to 43 in 2017. It reflects that 89 out of the 115 countries fail to make sufficient budget information publicly available. IBP states that this failure undermines the ability of citizens to hold their government to account for managing public funds.

Countries like New Zealand and South Africa (with scores of 89 each) topped the charts whereas Saudi Arabia scored 1, or for that matter Qatar and Yemen scored a 0, indicating that no budget information is made available in the public domain. The average score for South Asian countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) was 46 — an increase of 5 percentage points over the 2015 survey results.

To improve budget transparency, IBP suggests that India should draft and publish a prebudget statement and mid-year review. Pre-budget statements are published by nearly 50 countries, including India’s neighbour Afghanistan. It should also increase the information in the budget proposals by providing detailed data on the financial position of the government and extra-budgetary funds. India should also provide more information, such as comparisons between planned revenue and actual outcomes and a comparison between the original macroeconomic forecast and actual outcomes.

In terms of public participation, the Open Budget Survey (2017) gave India a score of 15 out of 100, denoting that few opportunities are provided to the public to engage in the budget process. Interestingly, this score is above the global average of 12. For improving public participation, IBP suggests introduction of a pilot mechanism (such as social audits) to enable the public and government officials to exchange views on national budget matters during monitoring of the national budget implementation. Among India’s neighbours, Nepal had the highest score of 24 on the public participation parameter. India tied with Afghanistan with a score of 15. Bangladesh followed with a score of 13.

In terms of budget oversight, India obtained a score of 48. The IBP said that the legislature and supreme audit institution (which is the Comptroller and Auditor General, or CAG) provided weak oversight during the planning stage of the budget cycle and limited oversight during the implementation stage of the budget cycle.

For the 2017 survey, documents that should have been published prior to December 2016 were assessed. India-based thinktank Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability, which partnered with IBP, said, “In terms of publishing timely and relevant information in the audit reports and yearend reports, India has scored well above other countries.”

Government revenues, expenditure

2012-17

Sidhartha, Spending by states grows at slowest pace in 13 years, May 29, 2017: The Times of India

Most Budget For 11% Increase In FY18 Against 19% in FY17

Amid low spending by the private sector, some of the top states in the country have slowed down spending due to their inability to increase the tax base.

During the current finan cial year, 17 major states have budgeted for a 10.8% rise in spending, compared with 19% last year, making this the slowest pace of increase in at least 13 years. As a result, general government spending is expected to grow 7.8% this year, less than half the 17% rise recorded last year, a study by Motilal Oswal economist Nikhil Gupta showed.

But the good news is that at 7.8%, the pace of increase in revenue spending is lower than capital spending, which creates assets and generates jobs. Capital expenditure is projected to rise by14%, faster this year than the long-term average growth of around 12%. Given that nearly 84% of states' budgets goes toward revenue spending, such as interest payments, there is very little left to undertake productive spending.

Devendra K Pant, chief economist at India Ratings, said, “Indian states are providing support to investment growth.The subdued investment is pos sible only because of the capital spending by the states. After the 14th finance commission award, the general apprehension was that states would spend on current consumption.On the contrary , the states have spent more on capital expenditure. On average, states spent 60% of their capex on building roads and bridges, power, and irrigation.“

This year too, the highest share of allocation is towards irrigation and flood control (23%), followed by transport (19%) and energy (8%). Of the overall revenue spending, education (18%) tops the list, followed by interest payments (12%) and pension (11%).

But the real worry is inability of states to increase the share of own tax revenue. States raise resources from four key areas -own taxes, nontax receipts, share of central taxes and grants from the Centre. Although tax collections are budgeted to grow over 14%, the highest in five years, as percentage of GDP it remains a modest 6.5%.

States are increasingly relying more on the Centre to meet their funding needs as the growth in states' own receipts has significantly lagged the rise in support from the Centre, which comes in the form of tax transfers and grants. While Centre's support has increased by nearly 30% in the past three years, states' own resources grew by only 10% per annum between 2013-14 and 2016-17, the report said.

Just three years ago, support from Centre was estimated at around 60% of states' own tax receipts, but now they are nearly equal following the recommendations of the last finance commission.

Financial year

2017: MP first state to go for Jan-Dec

MP first state to go for Jan-Dec fiscal, May 3, 2017: The Times of India

The Narendra Modi government is still mulling shifting the financial year from April-March to January-December, but Madhya Pradesh has already announced a merger of the fiscal and calendar years.

“The state cabinet has decided to change the financial year to January-December from April-March. The state budget will be tabled in December-January while financial closure will be done in December every year,“ state le gislative affairs and public relations minister Narottam Mishra told reporters after Tuesday's cabinet meeting.

The minister did not elaborate how the government would go about it especially when the Centre would be on a different schedule. He said the MP government would “try to finish the current budget proceedings by December this year“. “The next budget will be presented in December this year, or in January 2018,“ he added.

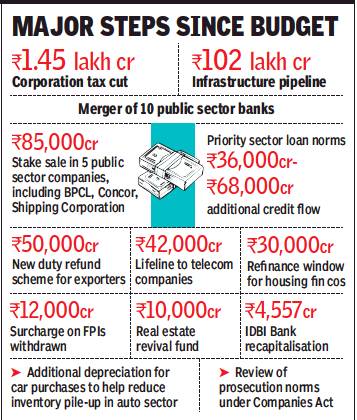

Major decisions taken outside the budget

1991, 2019

Sidhartha, January 31, 2020: The Times of India

From: Sidhartha, January 31, 2020: The Times of India

In 1991, the P V Narasimha Rao government ushered in major economic reforms — it opted to keep key decisions outside the Budget. In its second term, the Narendra Modi government, battling an acute economic slowdown, has been forced to announce a series of steps to accelerate activity. Instead of waiting for the Budget, the government chose to unveil steps — including one of the sharpest ever corporation tax reductions — months after Nirmala Sitharaman presented her first Budget in July 2019.

The series of steps announced by the government over the last few months would leave a Rs 2.9-lakh-crore impact on the exchequer, which is over 10% of the Centre’s Budget. Almost half of it is on account of a reduction in the corporation tax rate to 22%, along with a 15% levy on new manufacturing companies.

While it does impact the already strained fiscal situation, not all the outgo will take place during the current financial year. For instance, the income tax department is estimating a savings of up to a third of the tax reduction as all companies are yet to shift to the lower rate. Similarly, the new Rs 50,000-crore export scheme to refund levies will kick in from next year and will replace a leakage-prone Merchandise Export from India Scheme (MEIS). Even the government’s Rs 10,000-crore contribution to the proposed Rs 25,000-crore fund to revive stalled housing projects is unlikely to see an outgo in one shot, with at best a marginal amount of funds to be released during the current financial year.

In an interview, Sitharaman said that the Modi administration has responded to demands from various sectors. And, the steps have also shown that the Budget is no longer the sole event for making key economic statements. Of course, some of the announcements by the finance minister, which had almost turned into a weekly affair in August and September, included a series of steps that should have been taken during normal course of business.

In its first term, the BJPled government had moved ahead with the goods and services tax (GST), which took away the powers of the state legislature as well as Parliament to decide levies, ranging from excise duty, VAT and service tax on almost the entire set of items.

With a committee headed by former Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) member Akhilesh Ranjan having submitted a draft of the new income tax law, all eyes are now on Sitharaman to see if she pushes for its enactment, which may end the annual suspense over reworking tax slabs and increasing exemptions and deductions.

The revenue moves of Finance Ministers

2012-19

From: Sep 21, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

The revenue moves of Finance Ministers, 2012-19

The stock market after the Budget speech

2020: the biggest loss for investors on a Budget day

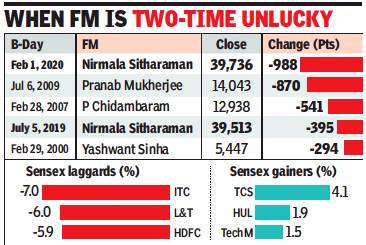

February 2, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 2, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 2, 2020: The Times of India

Nirmala Sitharaman disappointed Dalal Street investors with her second Budget on multiple fronts: She shifted the burden of dividend tax from corporates to recipients in a move that will hurt promoters, didn’t give in to expectations of abolishing longterm capital gains tax on equities, and raised fiscal deficit targets that is expected to keep rate of interest at an elevated level.

As a result, the sensex crashed 988 points — the biggest single-session points drop on a Budget day — to close at 39,736, a threemonth closing low. The day’s sharp dive in the market also left investors poorer by Rs 3.5 lakh crore with the BSE’s market capitalisation now at Rs 153 lakh crore.

In the session, HDFC group was hit the sharpest as the market expects a tough time for financial sector firms if interest rates remain sticky. In addition, insurance and mutual fund companies were hit by the FM’s proposal to do away with IT exemptions for individuals in favour of lower income tax rates. HDFC, ITC, ICICI Bank and HDFC Bank accounted for most of the sensex’s slide, while a higher closing for TCS, HUL and Infosys cushioned the fall marginally.

The FM, however, changed some rules which are expected to enthuse foreign funds to invest in India. According to Edelweiss Group chairman & CEO Rashesh Shah, the FM has sent out a very positive signal to foreign investors through exemptions to sovereign wealth funds to invest in infrastructure and the abolition of dividend distribution tax, “to reaffirm their faith in the India growth story”. Institutional dealers too feel that with central banks readying to pump in cash to revive a slowing global economy, FPIs are expected to continue to buy into the India story.

On the other side of the spectrum, market’s expectations about strong fiscal and other measures to bring the economy back on track, were not met. “The proposed listing of LIC, abolition of dividend distribution tax are positives but markets were hopeful of fiscal measures to kick-start the economy and the Budget fell short on this count,” said Raamdeo Agrawal, chairman, Motilal Oswal Financial Services.

The day’s selling was across the board with both BSE’s midcap and smallcap indices closing 2.2% lower. Among the sectoral indices, real estate, capital goods and industrials lost the most with IT and tech indices closing with marginal gains. The session also recorded a net foreign fund outflow of Rs 1,200 crore while domestic funds were net buyers at just Rs 37 crore, BSE data showed.

Dalal Street players feel stocks may fall some more when trading opens on Monday but thereafter the news about the spread of coronavirus globally and the quarterly numbers in the domestic market would give directions to the market. Investors globally are turning cautious about the spread of the virus from China and this may lead to volatility across the world, including in India, they said.

Secrecy

As in 2019

June 10, 2019: The Times of India

Does Union Budget really need to be this secret?

NEW DELHI: The secret mission started on Monday as the Narendra Modi government got down to prepare its first budget of its second term. North Block, which houses the finance ministry, will be in 'quarantine' from today (out of bounds for visitors and media) until the presentation of the budget on July 5.

Hawk eyes: During the 'quarantine' period, all the entry and exit points of the ministry will be guarded by security personnel while the Intelligence Bureau personnel, assisted by Delhi police, will keep a close watch on the movements of those entering the rooms of officials involved in the Budget-making process. Electronic sweeping devices have been installed and private e-mail facilities to most computers in the ministry blocked.

A blue sheet: A secret sheet known as Blue Sheet (as the colour of the sheet is blue) is maintained during the budget preparation process and contains the key economic numbers that form the basis for the budget's calculations and is updated as new data come in. It's one of the biggest secrets of all the budget's elements. Only the joint secretary (budget) is given custody of the secret paper and not even the finance minister is allowed to take it outside the ministry premises.

Fort Knox: It gets even more secretive when the printing of budget papers starts. During this two-week period, those who oversee the printing aren't even allowed to go home, remaining sequestered within the North Block basement area where the presses are kept. To prevent any cyber theft, the computers inside the press area are delinked from the National Informatics Centre (NIC) servers. By the way, leaking of budget documents is punishable under the Officials Secrets Act.

The history: While an element of secrecy was there in almost all Union budgets, it became even more stringent after a certain portion was leaked in 1950 when the printing of the budget used to take place at the Rashtrapati Bhavan. The same year, the printing venue was moved to a government press in Minto Road and then since 1980, the basement in North Block has become the place for budget printing.

Why keep it secret? Some experts say that this level of secrecy isn't needed given that major government announcements including indirect tax rates (GST) are not part of the budget anymore. In some countries, the budget is put in the public domain up to three months before it is presented. But then the meticulous secrecy is also a well-preserved British legacy like the budget briefcase that the finance minister carries on the budget day.