MG NREGS (Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme)

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Annual statistics

October-November 2016

The Times of India, Dec 13 2016

MGNREGA hires plummet by 23% in notebandi November

Subodh Varma

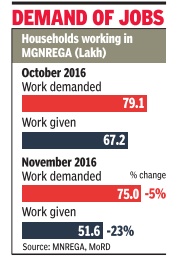

The Modi government's demonetisation move seems to have taken the wind out of the sails of an already faltering job guarantee scheme. The number of households getting work in November dropped by 23% compared to the previous month and those being turned back empty-handed jumped to a staggering 23.4 lakh, almost twice the number in October.

Compared to the same month last year, work given this November is down by over 55%, indicating this is not a seasonal decline peculiar to November. With the overall emp loyment situation grim, this dip in jobs is expected to increase distress in rural areas. If there was work available (in MGNREGA), we would have got some relief at least. Now we get casual labour work at just Rs 50 per day , sometimes. Mostly we are just sitting, waiting,“ says Suniya Laguri, a 20-year old woman in Jharkhand's West Singhbhum district.

Suniya is voicing a concern that finds echoes across India in greater or lesser measure. Rural wages have crashed due to non-availability of cash as well as the desperation of the poorest -agricultural labourers and small or marginal farmers -to try and earn something in order to survive.

Mangoo Ram of Hardoi district in UP says his family survived the first few weeks by getting basic food items on credit and cutting down on an already minimal consumption. But now, in the fifth week of demonetisation, the situation is dire.

Most of the wages earned for work under the job guarantee scheme are deposited in banks or post offices. So, why has work itself suffered so much? The answer is not clear, with people citing different reasons. Shankar Singh of advocacy NGO Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan in Rajasthan says everybody -MGNREGA employees as well as people seeking work -were too preoccupied with standing at banks or post office lines for the first few weeks. This directly affected the whole system.

“Already , there was a squeeze on expenditure, with government not releasing adequate funds and gram panchayats overstretched. Notebandi has come on top of that, that is why this problem,“ Singh said.

Till December 12, gram panchayats were in the red to the tune of an incredible Rs 37,000 crore, according to the latest financial summary available with the rural development ministry .

That is, they had spent this much money but had yet to receive it from the top.

On the other hand, state governments had with them more than Rs 13,000 crore in funds that were yet to be transferred downwards.

There seems to be some efficiency issue also: in some states, work given under the scheme in November is not as bad as in others.

But the resultant ripples are evident all round.

The main issue is that banks are just not getting enough cash to dispense and people are waiting 4-5 hours to get Rs 200. Many return without any money .

With the reported return of thousands of migrants, the situation has worsened in rural areas as there is an army of unemployed in villages. Sowing for rabi (winter crop) is in progress but it cannot absorb everybody . This was the right time for the job guarantee scheme to open its doors wider and provide much needed relief. But that was not to be.

2016-17 (record year) vs. 2017-18 (a housing-inspired spike)

Eight key states logged a massive increase in demand for work under the job guarantee scheme MGNREGA this fiscal, an increase that is seen as astronomical in the history of the programme.

Three other states saw high demand during the earlier part of the year but have registered a sharp fall in later months. Still, the annual demand for work under MGNREGA is projected to stay below or, at best, touch the levels of 2016-17.

Curious is the story of MGNREGA in 2017-18 when the scheme swung from being reviled by the ruling BJP as a “shame” to having to tap extra funding to tide over demand of the last four months. The rural development ministry this month pumped in Rs 7,000 crore more, securing Rs 3,500 crore from the finance ministry and mopping up the rest from savings in its other schemes.

What makes for interesting reading is MGNREGA notching lakhs of extra ‘persondays’ of work across Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal.

As the high demand for distress labour across poor and rich states lends itself to comments about rural stagnation, the rural development ministry attributes it to work being done under the rural housing scheme.

Secretary, rural development, Amarjeet Sinha, said 54 lakh houses were in different stages of construction under PM Awas Yojana where each house was being supplied with 90 days of labour from the job scheme. Also, a quarter of the expenditure under the PM’s rural road scheme came from MGNREGA, he added.

Despite the spike, according to the ministry, the demand for work is projected to touch 225 crore ‘persondays’ in 2017-18, as against 235.75 crore ‘persondays’ in 2016-17.

Chhattisgarh registered a sharp rise in demand, monthon-month, over 2016-17 — 1.18 lakh in August, 2.58 lakh in September, 4.27 lakh in October, 6.57 lakh in November and 7.86 lakh in December.

In Gujarat, the last five months saw an extra demand of 72800, 76825, 43239, 84842 and 46574 ‘persondays’.

The increase in ‘persondays’ in Jharkhand in the last five months was 2.9 lakh, 3.9 lakh, 4.12 lakh, 3.5 lakh and 1.2 lakh. The same trend of jump in demand was noticed in MP

(39.5 lakh persondays), Maharashtra (11.35 lakh) and Rajasthan (10.66 lakh).

2019-21

Subodh Ghildiyal, January 17, 2021: The Times of India

Job scheme sees record work, but share per family drops

From 48.4 Days In 2019-20 To 44.38 In 2020-21

New Delhi

As the demand for work under MGNREGS during the pandemic unemployment shot through the roof, the share of work per household slipped by four days.

Surprising as it seems, the average employment per household was 48.40 days in 2019-20 when the number of families that worked under the job scheme was 5.48 crore. In contrast, the employment per household has gone down to 44.38 days in 2020-21 when the number of families has zoomed to 6.90 crore. Under MGNREGA, every household is entitled to 100 days of work per year.

Also, total persondays generated in 2019-20 was 265.38 crore as against 306.39 crore in the pandemic year when formal employment took a serious hit due to the lockdown.

It implies while more households sought and found work under the job scheme this year, the individual share of employment was lower. Interpretations and reasons vary. While the government believes the temporary share in MGNREGA of migrants who returned to villages skewed the figures, job scheme activists say the administrations have not been able to generate work owing to the surge as well as budgetary constraints resulting in a serious gap between the demand and work given.

“The overall figures may be hiding two averages. The migrants sought work in villages and later went back to cities. These additional workers are not seeking work any more under MGNREGA but are dragging down the per family share. If the migrants are taken out of the calculation, the work per household may go up. It requires a detailed study,” a senior rural development ministry official said. The rise in work demand without concomitant increase in work per household (HH) is a national pattern.

In Uttar Pradesh, the average HH work dropped from 46 days in 2019-20 to 38 days in 2020-21 even as the number of families working went up from 53.14 lakh to 88 lakh. In Bihar, it has fallen from 42 days to 39 days, Chhattisgarh from 55.69 days to 43.17 days and Maharashtra from 41 days to 35 days. Here, Odisha and Madhya Pradesh are exceptions — Odisha per HH average has gone up from 48 days to 49 days and in MP, from 53 days to 55 days. It is to be seen if the remaining two and half months in the financial year change the average since overwhelming number of migrants are said to have since returned to the cities.

Fund allocation

2013-16

Half of the fund allocation under job scheme MGNREGA goes to five states, but only two of them, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, rank high on the poverty list.

The paradox that poor states are not partaking of “distress labour“ scheme has been underlined by the Sumit Bose committee set up to analyse welfare schemes of the rural development ministry and suggest ways to prioritise beneficiaries.

A break-up of the fund flow under the job scheme between 2013-2016 shows that Andhra Pradesh (AP), Tamil Nadu (TN), UP, Bengal and Rajasthan have accounted for half of the allocations. AP, TN and Rajasthan are low on the list of deprivation or degree of poverty. In contrast, Bihar and Maharashtra are not among the top five states despite having “greater concentration of deprived households“, as mapped by rural household survey socio-economic caste census (SECC).

The expert panel's findings are in consonance with the general understanding that hard labour offered by MGNREGA should have greater demand from states with higher degree of poverty . The Bose panel has recommended that the scheme's focus should be more on poor regions.

Insiders acknowledge the paradox but attribute it to the nature of MGNREGA which is universal and demand-driven. Sources in rural development ministry said the scheme cannot be selectively focussed on poor states as it has to respond to demand whereever it emanates from. An earlier attempt to focus only on 2500 backward blocks kicked up a major controversy in 2015.

However, a top official said the skewed relationship between poverty and work demand has been noticed and the ministry is building systems to help poor regions leverage MGNREGA better.Sources said instead of limiting the scheme to poor areas, the ministry has launched a concerted campaign to target families which have reported deprivation under SECC.

All gram panchayats have been asked to ensure that deprived households are issued “job cards“ so that they are encouraged to seek work.The campaign has a special focus on 2569 poorest blocks, as identified by the erstwhile plan panel. “The labour budget and employment has shot up in Rajasthan, UP , Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Assam, Odisha in 2016. We've tried to push up work there,“ he said.

2008- 24

From: Atul Thakur & Rema Nagarajan, February 2, 2023: The Times of India

See graphic:

Annual outlay for NREGS 2008- 24

2015- 20

Atul Thakur & Rema Nagarajan, January 30, 2023: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: If the government were to actually provide 100 days of work to every household registered under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGS), it would need to allocate over Rs 1.8 lakh crore in the coming Budget assuming the number of households opting for the scheme remains at the current level.

What has actually happened is a steady shrinking of the outlay after the Covid period boost to under half this amount. On average, the government provided only about 48 days of work per household in the five years preceding the Covid years (2015-16 to 2019-20).

Despite the Niti Aayog report of 2020 on the impact of MNREGS on household income and poverty alleviation stating that the scheme is a "powerful instrument for inclusive growth in rural India", the number of days of work provided remains barely half the promised 100 days. Any increase in the number of days would require substantial enhancement in allocation. For instance, providing even 60 days of work would require about Rs 1.1 lakh crore while providing work for 80 days would require roughly Rs 1.5 lakh crore.

In 2020-21, the Covid year, the spending on MNREGS soared to touch Rs 1.1 lakh crore, the highest annual spend on the scheme. The very next year, this fell to Rs 98,000 crore according to the revised budget figures. The allocation in 2022-23 is Rs 89,400, with the addition of the supplementary grant of Rs 16,400 crore to the original budgetary allocation of Rs 73,000 crore.

How do we reach the Rs 1.8 lakh crore figure? In the past five years, the annual average increase in wages is 5.1%. Assuming this remains true for the coming year, the average wage of Rs 217.7 per person per day in the current year would rise to Rs 229 in the coming financial year. Assuming the number of households provided work remains the same, the wage bill alone would be about Rs 1.3 lakh crore. With the addition of material and administration cost at the same ratio as this year, the total cost for the central government would be over Rs 1.8 lakh crore.

How much would need to be allocated to maintain the average of 48 days per household for the coming year? Similar calculations show the number would have to be a little over Rs 87,500 crore. However, allocations have to also take into account pending wage bills from the previous year. The pending bill in January 2022 was Rs 3,358 crore, according to government. Assuming similar pendency, MNREGS spending would have to be more than what has been allocated in 2022-23.

Impact

Destroyed factory jobs, discouraged skill development

As Budget Day draws near, economic policy makers in the country are likely to shift their attention to the allocation of funds to various programmes planned for the upcoming year. Nrega is one such programme. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act aims to provide at least 100 days employment to the rural unemployed and underemployed by engaging them in rural infrastructure building.

While well-intentioned, our research based on careful study of employment and operating data from factories show that Nrega has led to some interesting consequences: factory jobs have declined by more than 10% and mechanisation has increased by 22.3% as a result of implementing Nrega.

It may have led to the migration of workers from higher value productive factory work to digging pits and filling them, with factories choosing to mechanise faster instead of replacing these workers. Nrega beneficiaries are required to exert some effort in order to earn a minimum wage. The purpose of such a requirement is to prevent those who are otherwise gainfully employed from crowding out these jobs and to ensure that only the truly unskilled and unemployed take up these jobs. Our research reveals that what transpired in practice was very different.

We looked into how implementing Nrega in a region adversely impacts the availability of labour for nearby factories, using factory-level data from the Annual Survey of Industries across the period 2002-10. Since our data includes time periods before and after Nrega was introduced, we are able to perform a pre-post analysis. Our results show that nearly 10% of the permanent factory workers jettison their factory jobs to join the Nrega bandwagon.

Why would a factory worker prefer 100 days a year of minimum wage Nrega work building rural infrastructure over an entire year's work at wages higher than minimum in a factory? We show that Nrega work is unlikely to involve a lot of effort. More importantly , workers may prefer the 100 days of guaranteed and effortless work near home to a high-effort high-risk factory job far from home. Having a job close to home also means less out-of-pocket expenses on travel, clothing and other requirements of factory work.

It is quite possible that such workers either work as contract workers in factories or do odd jobs in their villages during non-Nrega days. There was no decline in contract workers so it is plausible that the outflow of contract workers to Nrega was offset by erstwhile permanent workers turning into contract workers.

How did factories respond? Consider a factory whose cost of production is Rs 100 per unit if it employs workers and Rs 110 per unit if it employs machines to do a job. Naturally , the factory is likely to employ workers. Now if because of the availability of the Nrega option, workers demand Rs 120 per unit, the factory is likely to find using machines cheaper and let the workers go. This is indeed what we found.

Note that if the increase in wages is a result of increased productivity, per unit cost remains unchanged and hence factories are likely to continue employing workers as before.

Why is this migration of factory workers to Nrega undesirable? First, it defeats the very purpose of workfare, which is to prevent the already employed from cornering workfare jobs at the expense of truly unemployed. Second, this phenomenon negatively impacts both the Make in India and Skill Development programmes launched by the Centre. Factories that do not have access to ample financing to mechanise and cope with the labour shock engineered by Nrega may be forced out of business.

Third and most importantly , Nrega may be turning skilled factory workers into unskilled pit fillers (since Nrega discourages the use of machines of any form) while the really unskilled continue to be unemployed. Impact on skill development is severe and may have deeper consequences for human capital development in India as a country .

Our findings show that it is important to not just focus on allocation but also on programme design. From a societal point of view, there is a need to redesign Nrega to encourage skill development and discourage entry of gainfully employed productive workers. Imposing quantity and quality based output targets for the programme could be a first step in this direction.

Significance in creation of employment

Ashok Gulati and Sameedh Sharma, Feb 24 2017: The Times of India

Can MGNREGA move from being a `living monument of UPA's failure' to a development scheme?

In 2017 in his budget speech, finance minister Arun Jaitley proudly announced allocation of Rs 48,000 crore for MGNREGA the highest since the inception of the scheme. However, this the comes nearly two years after Prime Minister Narendra Modi describing the scheme in a speech delivered to Parliament on February 27, 2015 “a living monument of the UPA's failure“.

The question, then, is what has changed for Modi and Jaitley? Have they realised the importance of the scheme as a safety net to fall back on during drought years, or are they going to turn it from essentially a dole into a development scheme?

Since FY09, when the scheme had a pan India roll out, expenditure for MGNREGA has grown at an average of 7% per annum in nominal terms. But in real terms measured at 2011-12 prices (by using CPI-AL as deflator), it has actually been decreasing till FY15, and then improved marginally . Still, the budgeted expenditure in FY18 is roughly about 28% lower than the revised estimate of FY10 in real terms (see graph).

But how has the scheme performed in terms of creating employment opportunities in the last nine years?

During periods of drought when marginal farmers and labourers alike are most vulnerable, MGNREGA is supposed to work as a social safety net by offering assurance of employment and income. In FY10, the number of households given employment and the total person days generated was the highest (see graph, RHS), owing to 2009 being a drought year. But this hasn't been the case.

MGNREGA failed to serve as a fall back option for the poor during two consecutive droughts in 2014 and 2015. In fact the figure shows MGNREGA in FY15 generated the least number of person days and household employment since the start of the scheme. Although the following year saw an increase, it went down again in FY17.

This happened despite the government's January 2016 announcement that it would increase the number of days from 100 to 150. Thus, the scheme as a safety net did not come up to expectations in providing relief to poor workers and even marginal farmers during the drought of FY15.

However, it is interesting to observe that across states, the impact of MGNREGA has been ironically better in the relatively well-off states and worse in the poorer states. In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, where poverty levels are about 30% of the state population and which also hold a third of India's poor the level of employment created by MGNREGA has been disappointing.

Average number of days provided in both UP and Bihar were 34 and 45 days in FY16, the second year of back to back drought. These person days were much below the promised 100 days of employment. Contrast this with richer states like Tamil Nadu where average number of days of employment in FY16 was 61.

It is evident that lack of governance and high leakages in the poorer states is leaving the impoverished even more vulnerable. It is also interesting to note that the female participation in MGNREGA has gradually improved from 48% in FY09 to 57% in FY17 at all-India level.However, in Tamil Nadu and Kerala it is above 80%, but remains much lower in states like Assam, UP, Bihar and Odisha.

MGNREGA also suffers from untimely delivery and poor quality of assets created. The FM's announcement to construct another five lakh farm ponds under the scheme gives no assurance of quality and utility . The lack of a proper evaluation of asset quality by a third party leads us to the question whether MGNREGA has the potential for being an investment oriented model.

With so much spent on the scheme, the returns from it in areas like irrigation have not been satisfactory.Moreover, work completion rate is also a concern. Of the target 12.4 lakh farm ponds in FY17, so far only 4.5 lakh (or 37%) have been constructed. The promise to build more farm ponds in this budget is simply pushing ambition higher than is achievable.

Nevertheless, it isn't as if the government is lacking the drive to improve the scheme. The June 2016 agreement between the ministry of rural development and Isro to geo-tag all assets constructed under MGNREGA is the right step ahead. Use of space technology to monitor and identify completed and under construction assets will not just improve outcome realisation but also transparency and accountability .

MGNREGA's geo-tag platform `Bhuvan' is a user interactive visual interface that provides information on the assets already constructed. However it is still at an infant stage and the FM's claim that it has established transparency is a bit premature.

Moreover it still remains unclear what direction MGNREGA is headed towards. Its near decade long experience does not bring much solace. Real expenditure has decreased; the scheme's performance during droughts has been mixed; and assets constructed are mostly inferior. If the government is to avoid the embarrassment of MGNREGA becoming a living monument of NDA's failure, it must do more than just hiking up allocations.

Ashok Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Sameedh Sharma is Research Assistant at ICRIER

Technology undoes NREGS in Jharkhand

The Times of India, Feb 16 2017

Going online was sup posed to clean up and smoothen functioning of government programmes, like the rural job guarantee scheme MGNREGS. But experience from Jharkhand's tribal districts shows that besides chronic lack of connectivity ,a brand new system of corruption has emerged. And, instead of more transparency , villagers with no knowledge of the electronic way of life are running blindly from pillar to post.

Digital signatures of gram pradhans are stored in `dongles' and used for illegal money transfers. Arbitrary deletion and addition of names or photographs has damaged credibility of muster rolls.Wrong photos are uploaded on job cards, and payments are going into accounts that workers are not even aware of.

These worrying facts emerge from months-long study and interaction with villagers in the tribal districts of West Singhbhum, Godda, Khunti, Gumla and others by Ankita Aggarwal, a social activist. “The Centre has been issuing direction after direction, instead of letting states implement the programme according to their needs and capacities. One recent report in a newspaper showed that Centreand statelevel officials were part of a WhatsApp group for communication that makes it hard for people seeking information under RTI,“ she told TOI.

“The computer operator has emerged as a new node of corruption. If middlemen collude with the computer operator, it is fairly easy to siphon off wages by generating fake muster rolls,“ said a block development officer in Khunti district.

Funds are electronically transferred to accounts of workers and vendors after Fund Transfer Orders (FTOs) are signed digitally . Most gram panchayats lack internet connectivity and have no computer operators. So, FTOs have to be signed from the block office.But it is difficult for gram panchayat presidents and secretaries to repeatedly travel to the block headquarters, and in any case they are unfamiliar with the system. Solution? Many have given their digital signature in a dongle to blocklevel functionaries.

Unsurprisingly , these digital signatures are also being used to authorise fake payments without the knowledge of the owners of these signatures. An FIR was recently lodged against Santosh Kisku, mukhiya of Godda district, whose digital signature, kept with the block functionaries, was used to authorise payments for work done by a machine. Kisku said he had no notion that his signature could be thus misused. “I was in Ranchi when my sign appeared on fake documents,“ he said.

Normally , it takes a couple of days for the electronic fund transfer to get processed through the system. If there are technical glitches, it can take months. It is impossible for workers to demand accountability for these delays as payments are beyond the control of the gram panchayat or even the local administration once FTOs have been signed.

MGNREGS provision for compensation for not getting work, too, has become complicated as the functionaries do not accurately record the date of application for work in the Management and Information System (MIS). The exercise of recording demand is simply not done for workers who are not allotted work. As a result, workers across Jharkhand are almost never paid unemployment allowance even though denial of work is routine.

The Centre's insistence on payment of wages only into the bank account linked to the worker's Aadhaar number has created its own set of problems, as Abhimanyu Sau, a worker of Gumla district, found out.

He was unable to trace several months' wages for work done under MGNREGS. The MIS showed that his wages had been credited to his account. After several weeks of panic, a consultant with the rural development department helped him.

It was found that Sau had two accounts in the bank. To meet account opening targets under the Jan-Dhan Yojana, many MGNREGS workers were forced to open another account linked to their Aadhaar number.

Their wages get credited to their Jan Dhan account, and not the earlier one. Many workers remain unaware of this change, and some even gave up working under MGNREGS due to this reason.

Wages

Indexation to rural inflation proposed

From: Subodh Ghildiyal, RD ministry to finmin: Index NREGA wages to rural inflation, June 6, 2018: The Times of India

Move Will Hike Income

In a bid to ensure higher returns for labourers in MGNREGA, the Union rural development ministry has again asked the finance ministry to index the wages under the job guarantee scheme to Consumer Price Index (rural) in place of the current CPI (agricultural labourers).

The RD ministry has argued that CPI (R) better reflects the present consumption pattern among rural households unlike CPI(AL) which is an old basket of measurement. The CPI (AL) has a greater weightage for food items, whose prices have dipped after the advent of the National Food Security Act.

According to sources, the switch in indexing would result in hike in wages and put an annual financial burden of Rs 2,500 crore on the Centre.

The annual wage revision under the job scheme has for years resulted in minimal, negligible, hike across states, sparking outrage from activists. The hikes have been as low as Re 1 in some states while some have registered no increase at all. Then too, RD officials had blamed the no-show in wage hikes on CPI (AL). The renewed push for change in methodology for wage revision under MGNREGA comes in the wake of strong differences between the ministries of RD and finance over the issue.

Following the recommendation for change by Nagesh Singh Committee set up by RD ministry, a reference was sent to the finance ministry this year. However, the latter refused to agree, questioning the rural ministry on the need for change and if it had worked out the additional financial burden.

Payment below minimum wage: 2020-21

AtulThakur & Rema Nagarajan, January 26, 2022: The Times of India

From: AtulThakur & Rema Nagarajan, January 26, 2022: The Times of India

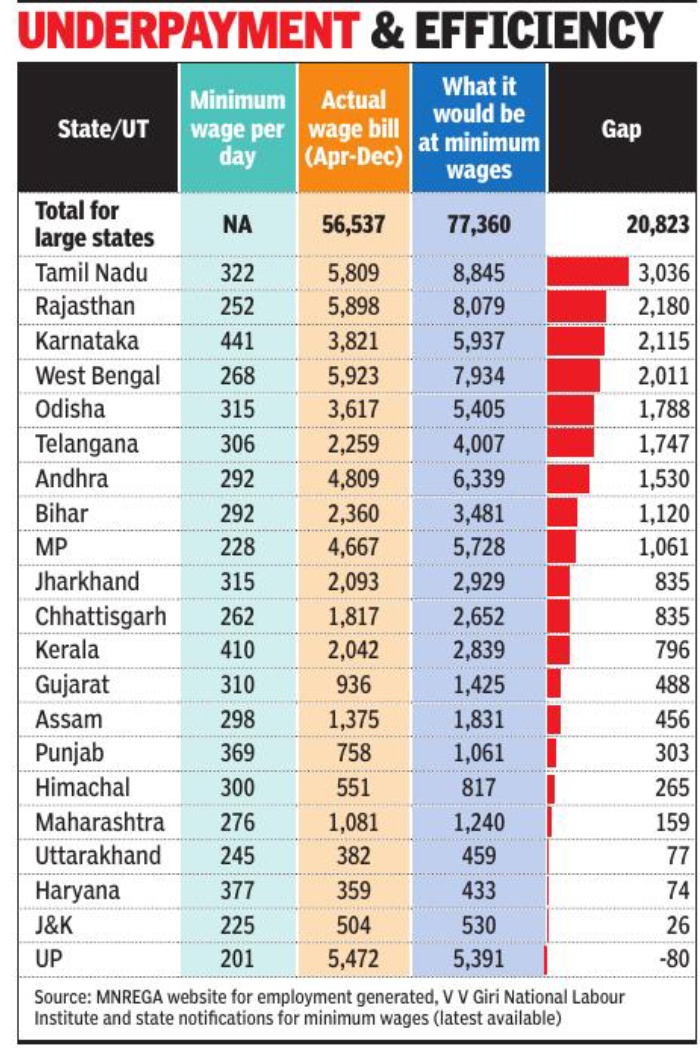

The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGS) may be seen as one that offers relief to the poor in distress, but those poor ‘beneficiaries’ are in fact subsidising the creation of infrastructural assets to the tune of over Rs 20,000 crore a year, an analysis of its wage bill suggests. By paying MNREGS workers well under minimum wages, the government saved nearly Rs 42,000 crore in just the last two years, a period in which the poor faced severe economic distress due Covid-induced disruptions. The minimum wage ranges from Rs 441in Karnataka to just Rs 201 in Uttar Pradesh. In almost no state were MNREGS workers paid the minimum wage, though it is supposed to be the barest minimum required for subsistence level existence. The minimum wage fixation (itself disputed by experts) is done by considering the most basic nutritional intake for human survival. Time and again, the Supreme Court through several judgments has also elevated the right to minimum wages from a statutory status to constitutional status. The SC has also ruled that wages less than minimum wage amount to “forced labour”. Work under MNREGS is hard manual labour used for building rural infrastructure such as water conservation structures, roads, houses under PM Awas Yojana and land development. In effect, all of this is being subsidised by the poorest through their underpaid labour. TOI looked at data on person days of work generated under the scheme and calculated what the wage bill would have been at minimum wages. We then compared this to the wages actually paid to see how much was saved. We used the minimum wage for agricultural labour, typically the lowest of the minimum wages in each state, and where that was not available, the closest proxy.

The highest savings were in states which provided more person days of employment and had the highest minimum wages, while in those which provided hardly any work under MNREGS or have very low minimum wages, there was little or no saving. Thus, in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, which have among the highest minimum wages, the government saved the highest amounts of Rs 3,038 crore and Rs 2,115 crore in April-December 2021. Rajasthan and West Bengal have much lower minimum wages but generated more person days under the scheme and thus the savings in them was over Rs 2,000 crore each. Uttar Pradesh was the only state where the actual labour bill under MNREGS was higher, tho- ugh only slightly, than the calculations at minimum wages. But then, UP has the lowest minimum wage rate for agricultural labour and has not revised them for the past two years.

Prof Ravi S Srivastava, director of the Centre for Employment Studies at the Institute for Human Development, pointed out that the total cost of providing appropriate wages would not be much, but the government has resisted an increase in MNREGS wages despite two of its own committees recommending it. “No justification has been provided for MNREGS wages not corresponding to legal minimum wages, but this has been a long standing practice. MNREGS is a very productive programme that creates basic rural infrastructure. In a crisis it makes sense to invest in short gestation period infrastructure which will be more labour intensive and can increase earning of workers. Studies going back 20 years have shown that this has a cascading effect on the economy by increasing demand. The notion that MNREGS is just a social scheme or that expenditure on the poor is relief expenditure is wrong. You are paying the poor to do very hard work and in the process creating rural assets/ infrastructure,” he said.

Government notifies revised MNREGS wages with effect from April 1 of every financial year after adjusting for changes in prices. According to a paper co-authored by Dr Anoop Satpathy, fellow at the V V Giri National Labour Institute, in 200607, the first year of implementation of the scheme, MNREGS wages were linked with the minimum wages notified by the state governments and varied from Rs 50 in Gujarat to Rs 125 in Kerala. In 2007-08, 10 states revised minimum wages and demanded more funds from the central government, which foots the entire labour bill for the scheme. The paper argues that this upward revision was not unreasonable as the Minimum Wage Act of 1948 empowers states to revise minimum wages according to price indices.

The wage revision created apprehension that the scheme might become financially unsustainable in the long-run and the Congress government, which had promised 100 days of employment per year at Rs 100 per day under MNREGS, delinked wages in the scheme from minimum wages. It is another matter that the average number of days of employment actually ranges between 44 to 52 days over the last five years. Even the fixation at Rs 100 was done arbitrarily as in states where minimum wages were lower, the MNREGS rate was hiked to Rs 100 while for states like Goa, Haryana, Kerala and Mizoram, where minimum wages were above Rs 100, these were protected and wages notified under MNREGS were also higher.