Lithium: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

A backgrounder

As in 2023 Feb

Chethan Kumar, February 11, 2023: The Times of India

From: Chethan Kumar, February 11, 2023: The Times of India

From: Chethan Kumar, February 11, 2023: The Times of India

From: Chethan Kumar, February 11, 2023: The Times of India

From: Chethan Kumar, February 11, 2023: The Times of India

On February 9, the Geological Survey of India announced that lithium reserves have been found for the first time in India in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). “...GSI, for the first time established 5.9 million tonnes inferred resources (G3) of lithium in Salal-Haimana area of Reasi district of J&K,” the statement read. TOI does a deep dive:

Lithium tales

Lithium (Li) was first recognised as an element in 1817 when Swedish chemist Johan Arfvedson analysed the mineral petalite. “The metal itself was first isolated in useful quantities in 1855. In 1869, Dmitiri Mendeleev correctly positioned it adjacent to sodium, with the alkali metals, in his then revolutionary periodic table of the elements,” as per the US Geological Survey (USGS).

With a specific gravity of 0.534, it is about half as dense as water and the lightest of all metals. In its pure elemental form it is a soft, silvery-white metal, but it is highly reactive and therefore never is found as a metal in nature.

“Lithium has an average concentration of 20 parts per million in the Earth’s continental crust. It is more abundant than some of the better-known metals, including tin and silver. Lithium occurs in most rocks as a trace element, with the lithium substituting for magnesium in common rock-forming minerals,” USGS says.

India reserves: 'Inferred Resources (G3)’

Most of us are now familiar with lithium — what with its uses ranging from mobile phones and laptops to electric vehicles? But before getting into where India stands, how this lithium from J&K can be used and more, it is important to understand one thing from the GSI statement:

'Inferred Resources (G3)’

Inferred Resources means “part of a mineral resource for which tonnage, grade and mineral content can be estimated with a low level of confidence. It is inferred from geological evidence and assumed but not verified geological and/or grade continuity. The United Nations Framework Classification for Fossil Fuel says that with the exception of past production that may be measured, quantities are always estimated and there will be a degree of uncertainty associated with the estimates.

This uncertainty is communicated either by quoting discrete quantities of decreasing levels of confidence (high, moderate, low). “A low estimate scenario is directly equivalent to a high confidence estimate (G1), whereas a best estimate scenario is equivalent to the combination of the high confidence and moderate confidence estimates (G1+G2). A high estimate scenario is equivalent to the combination of high, moderate and low confidence estimates (G1+G2+G3),” UN says.

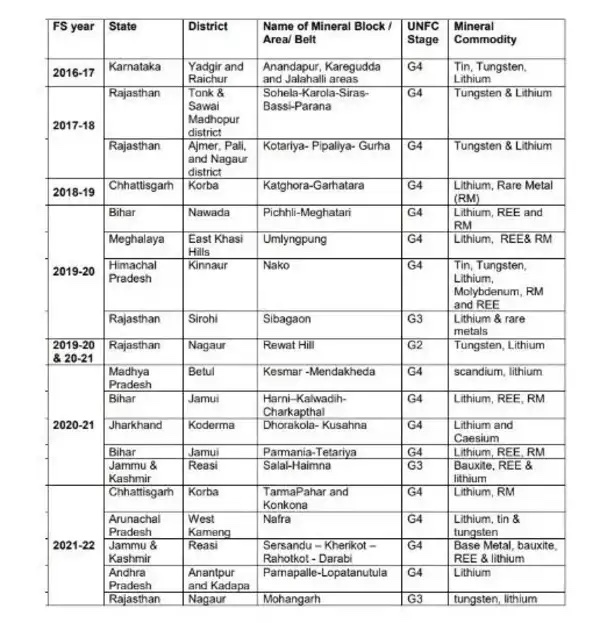

The G4 class, for instance, means the project is still at an exploratory stage. And according to the union ministry of mines & coals, here’s what India has been doing in the past few years:

Global reserves

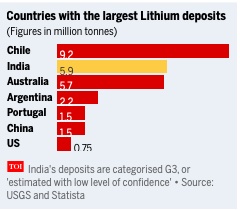

According to the US Geological Survey (USGS) Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2022: Identified lithium resources globally have been revised to 80 million tonne. However, reserves from which the element can be accessed as on date is pegged at just over 22 million with Chile leading the table (9.2 million tonne).

While the USGS break-up of data does not include the reserves in China, Statista, a global company specialising in market and consumer data, pegs it at 1.5 million tonne.

Lends itself to many uses

While lithium has many uses, the most prominent is in batteries for cell phones, laptops, and electric and hybrid vehicles.

Some key uses as per USGS include: Lithium added to glasses and ceramics for strength and resistance to temperature change; used in heat-resistant greases and lubricants, and it is alloyed with aluminium and copper to save weight in airframe structural components.

“Lithium is used in certain psychiatric medications and in dental ceramics. The lighter of two lithium isotopes — 6 Li — was used in the production of tritium for nuclear weapons,” USGS says. But the use with the greatest potential benefit to the most people in the world is in rechargeable batteries. These batteries take advantage of lithium’s light weight and high electrochemical potential and make it possible to power cars and trucks by using renewable, carbon-neutral sources of energy (for example, solar, hydro, or wind) instead of gasoline or diesel.

Lithium-ion batteries & India

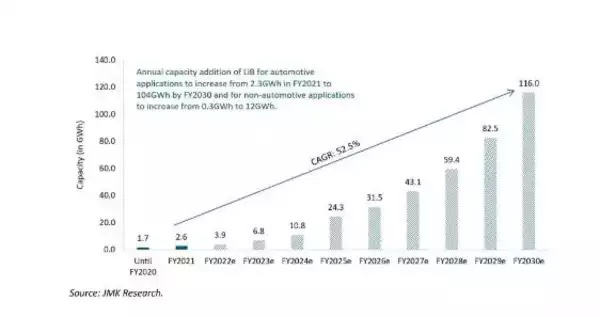

The introduction of Lithium-ion Batteries (LiB) has revolutionised numerous sectors, most prominently the EV industry. The adoption of LiB is accelerating in India and JMK Research — a specialist consultancy firm specialising in renewable energy — estimates that the annual LiB market in India will reach 116GWh in 2030, with EVs accounting for around 90% of the overall market on the back of huge government targets of adding variable renewable energy sources to the grid.

Key players in India

Of the total cost of LiBs, cells account for 65%, the battery pack 15%, BMS (battery management system) 15%, and the balance being the outer box, as per JMK Research. So far, battery packs and associated BMS manufacturing have entirely dominated the space in India and Indian manufacturers are able to produce most of the sub-components that go in a battery pack while thermal pads still need to be imported.

Similarly, BMS and outer box are also primarily supplied by the Indian battery pack assemblers. “However, since India does not have BMS manufacturing components, it sources pre-programmed protection circuit boards (PCB) from China and undertakes printing in India. The LiB pack manufacturing market in India is fragmented and comprises numerous active players including Coslight India, Okaya, Exicom, followed by Trontek, Amptek, Cygni, Grinntech, Lohum Cleantech, Pure EV etc.

In what was the first for the country, the Indian Space Research Organisation’s (Isro) Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre (VSSC) successfully developed and qualified lithium ion cells of capacities ranging from 1.5Ah to 100Ah.

This was for use in satellites and launch vehicles and Isro, after successful deployment of the indigenous lithium ion batteries in various missions, dedicated to transfer this technology to the industries to establish production facilities for producing lithium ion cells to cover the entire spectrum of power storage requirements of the country.

What is the govt doing?

The Centre, with a target for ensuring that at least 30% of new vehicle registrations be electric by 2030, has focused on developing the value chain for batteries — cells — and for the same, it encourages local manufacturing of lithium-ion cells.

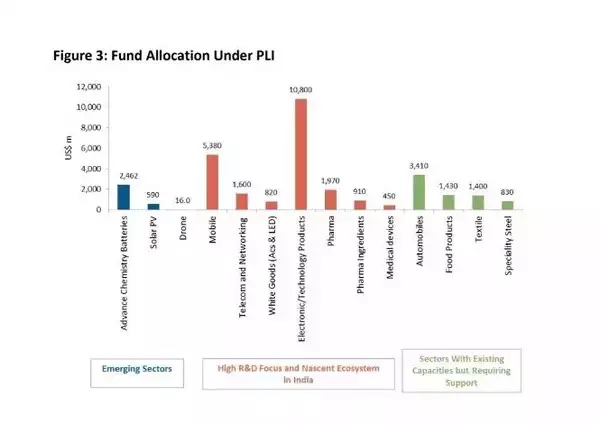

In April 2021, the Centre doubled import duty on lithium-ion cells to 10% and later announced a PLI (Production-Linked Incentives) scheme includes financial allocations for Advanced Chemistry Cell (ACC) batteries under the National Programme for Advanced Chemistry Cell (NPACC) and for automobiles and auto components with an emphasis on promoting local manufacturing.

Reserves

Salal-Haimana area of Reasi district of Jammu & Kashmir

Research- Rajesh Sharma, February 21, 2023: The Times of India

From: Research: Rajesh Sharma, February 21, 2023: The Times of India

From: Research: Rajesh Sharma, February 21, 2023: The Times of India

On February 9, the Geological Survey of India (GSI) announced that it had “for the first time established 5.9 million tonnes inferred resources (G3) of lithium in the Salal-Haimana area of Reasi district of Jammu & Kashmir." According to senior government officials, the lithium discovery is of the best quality. And with this discovery, India now has the seventh largest resource of lithium globally, though it will take time to convert this into reserves. So what is lithium? Lithium, a non-ferrous metal, is one of the key components in electric vehicle (EV) batteries. It is about half as dense as water and, in its pure, elemental form, is a soft, silvery-white metal. Being highly reactive, it is never found naturally as a metal. What does the government mean when it says “inferred resources” of lithium? Simply put, inferred resources indicate a preliminary stage of assessment where the “tonnage, grade and mineral content can be estimated with a low level of confidence”. That is, the presence of the mineral is “inferred” from geological evidence but not verified for viability. G1, G2, G3 etc are a measure of the confidence level as to the availability of a mineral. Lithium finds in India have mostly been of the G4 level, which indicates that prospects are of an exploratory stage.

Where does lithium typically come from?

There are two primary sources to obtain lithium:

Lithium brine deposits are accumulations of saline groundwater enriched with dissolved lithium. Although abundant in nature, only a few regions in the world, most in South America, contain brine.

Lithium found in ‘hard rock’ is a part of minerals hosted in pegmatites, rock units formed when mineral-rich magma intrudes from magma chambers into the Earth’s crust. As the magma cools, water and other minerals become concentrated.

Why is this discovery in J&K such a big deal?

The discovery is strategically important for India as it will go a long way in solving shortage of lithium, a key component of lithium-ion batteries used in EVs, harnessing solar power, wind energy and other chargeable instruments. All of which will help India’s efforts of moving towards a net zero emission goal by 2070.

Lithium is also added to glass and ceramics for strengthening, alloyed with aluminium and copper to save weight in airframe structures, and used in certain psychiatric medications.

Currently, India imports all the lithium it needs and in 2022, its imports amounted to almost Rs 14,000 crore. At current lithium prices, the current discovery is valued at a whopping Rs 34tn. What’s better? As against the normal grade of 220 parts per million (PPM), the lithium found in J&K is of 500 ppm-plus grading, say government officials.

How much lithium does the world have?

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) said in 2022 that total lithium resources globally stand at 80 million tonnes although the reserves from which it can be accessed were pegged at just over 22mn tonnes.

Though found on each of the six inhabited continents, Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia—together referred to as the “Lithium Triangle”—hold more than 75% of the world’s supply beneath their salt flats.

Why is lithium demand so high?

Booming global EV sales have led to lithium consumption to double over the past two years. Consumption is expected to reach 1.5mn tonnes by 2025 and over 3mn tonnes by 2030.

With suppliers unable to keep pace, a blistering price rally sent the total spot value of lithium consumption rocketing to about $35bn in 2022, up from $3bn in 2020, according to Bloomberg.

Can the discovery mitigate China’s lithium dominance?

China does not have too much lithium reserve of its own, but as the largest market for EVs, it has over half the global lithium processing and almost 75% of cell components and battery cell production in the world. Therefore, the proliferation of EVs could mean India becoming dependent on China.

J&K’s reserves, however, provide a major opening for India to be self-reliant. It will make EVs more affordable domestically, and India will also be able to tap into surging global demand.

What’s the environmental impact of lithium mining? Lithium is most often found in underground reservoirs, and mining it is known to contaminate and cut off scarce water sources in rural communities. Mining can also leave contaminants and toxic waste behind. There are other issues as well. One, extracting lithium from its ore is highly water-intensive — it takes about 2.2mn litres of water for one tonne of lithium. Two, the production process involves heating the ore at a high temperature that can only be cost-effectively reached by burning fossil fuels, meaning that for every tonne of lithium, 15 tonnes of carbon dioxide are emitted into the air. Finally, with the Himalayas being highly fragile and eco-sensitive, mining lithium may lead to long-term adverse consequences. Mining in the region is sure to attract opposition from environmentalists.

Is this really a new discovery?

In 1999 almost 24 years ago, the GSI had submitted a detailed report about the presence of lithium in the same area. But there seems to have been no meaningful follow-up until now.

A 67-page report in 1999, prepared by GSI scientists KK Sharma and SC Uppal had said “the prospect of lithium appears to be promising” in the Reasi belt, flagging high values of lithium “persistent throughout the belt”. The report had also credited MR Kalsotra, the then director for mineral investigation operations, for carrying out trace studies and reporting “high values of lithium” in 1992.