Bhitargaon

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Gupta-era temple

Akash Deep Ashok, Dec 18, 2023: The Times of India

From: Akash Deep Ashok, Dec 18, 2023: The Times of India

From: Akash Deep Ashok, Dec 18, 2023: The Times of India

From: Akash Deep Ashok, Dec 18, 2023: The Times of India

BHITARGAON’S 1500-YR-OLD MARVEL IN BRICKS

The Oldest Surviving Brick Temple In India

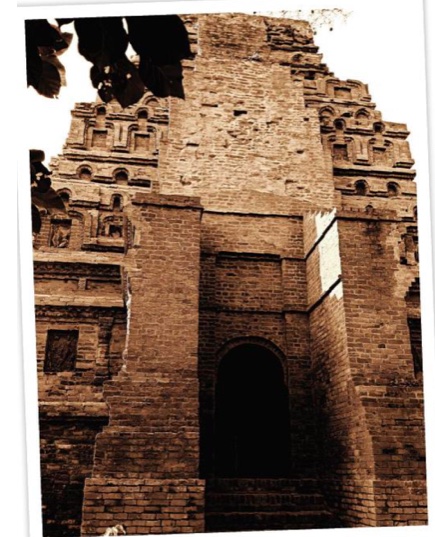

Hiding in the middle of a bustling town, 30 kilometres from Kanpur city towards Hamirpur, in a cluster of pucca houses crisscrossed by narrow bylanes, there is the temple of Bhitargaon. A billboard at the gate mentions: ‘Gupta-era temple’. A single plaque at the temple erected by ASI Superintending Archaeologist, Lucknow Circle, mentions that the temple is dated 5th century and has details of a few architectural features.

Its location is difficult to find even today in the era of Google maps. As one turns over pages of history, it turns out this was always the case. The temple has always been a serendipity to the seekers. The local residents have no idea about the scholastic importance of the ancient structure, nor any interest as the temple has no deity.

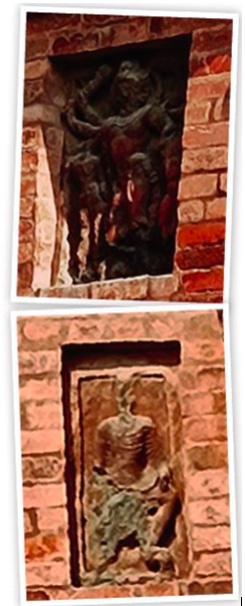

Heavily renovated, this brick temple with a few terracotta figures on the outer wall, a locked sanctum sanctorum and a shikhara that collapsed over 175 years ago is hardly a picture of joy. No wonder it has few visitors and far between. An aged caretaker deployed here by the ASI has nothing much to do. He sits on a bench on the lawns with a visitors’ register which sees no more than a dozen names even on a busy day.

But all that’s for an untrained eye. For the informed, this is a structure that withstood the ravages of time, survived the “great idol-breaking period” and escaped “the avarice of Mahmud, or the bigotry of Sikandar Lodi”.

An Arduous Journey & Discovery

In 1875, Joseph David Beglar, an Armenian-Indian engineer, archaeologist and photographer working in British India and reporting to the Archaeological Survey of India, visited Bhitargaon and found a temple that the locals believed was ancient. It was dilapidated and needed immediate conservation. Beglar, who was an assistant to Alexander Cunningham, the founder of the ASI, went back to Calcutta and showed his photographs to Cunningham who couldn’t believe his eyes. Cunningham’s old friend and noted Indian scholar, linguist and historian Raja Sivaprasad had also written to him earlier about the same temple, mentioning that it “possessed sculpture terracotta of a superior kind”. Despite his busy schedule and rigour of longdistance travel in those days, he was 64 then, Cunningham took the arduous journey – travelled in a boat all the way up from Calcutta to Kanpur and then took a horse carriage to reach this docile village. But in his own words, it was a just cause. In November of 1877, Cunningham stood right in front of what he believed to be the oldest temple made of bricks in all of India. He returned to the structure again in February 1878.

Antiquity & Scholastic Appeal

Cunningham concluded that this temple, with distinct features of Gupta architecture, was no later than 7th or 8th century or even older. “The Bhitargaon Dewal (as local referred to the temple back then) is the only specimen of an ancient brick temple now standing and this style of building would appear to have prevailed very extensively for several centuries…” he wrote. He concluded that Bhitargaon temple must have been part of the ancient city of Phulpur. The locals back then had no living memory of any prayers being held in the temple. Although they called the Dewal “pracheen” and had heard from their ancestors that its dome had been struck by lightning “2-4 years before the 1857 revolt”. From the terracotta figures on its outer wall, he concluded that it was a Vishnu temple. Jean Philippe Vogel, a Dutch Sanskritist and epigraphist who worked with the Archaeological Survey of India from 1901 to 1914, surveyed the temple in 1907 and placed it at least three centuries earlier than Cunningham’s estimate. Decorations on the temple at Bhitargaon are similar to those found on the Nirvana temple at Kasia, which could be dated to no later than the Gupta era, he wrote. Based on its architecture, pilasters and other features, both JC Harle and Percy Brown placed the temple around 450-460 AD.

Harle wrote, “The Daavatra temple at Deogarh, whose superstructure is largely conjectural, and the Bhitargaon temple near Kanpur, the sole survivor of the innumerable brick shrines which must have been raised in the Madhyadea during Gupta times, had higher, almost certainly curvilinear ikharas.” According to him, the large size of the bricks – the original bricks still retained in the inner chamber of the renovated temple are way too big for anything to be seen by the present generation – would “establish the Gupta date of this temple and 450CE would seem the latest”. Roughly, this would be the reign of Kumaragupta I (415-455 AD), the man who founded Nalanda University.

Conservation & Confusion

Ever since the temple was discovered by Cunningham, it has not stopped attracting scholars from all over the world. British archaeologist and art historian Albert Henry Longhurst visited it in 1909 and found the temple very dilapidated. After Cunnigham’s report made a splash in the British academic circles, PWD began conservation of the temple in 1884-85 but stopped due to paucity of funds. A second round of conservation was attempted in 1909 onwards. Ever since then, several attempts have been made to restore the temple. Although heavily restored, the upper half of the temple still remains untouched, as do the terracotta figures on the outer wall, which are now in advanced stages of decay. Since the temple has not witnessed any prayers in at least 170 years, there is a confusion regarding the reigning deity of the temple that was.

Historian Mohammad Zaheer in his 1980 book ‘The Temple Of Bhitargaon’ relies on iconographical analysis to disagree with Cunningham’s assertion on this being a Vishnu temple. He said that as Ganesha is present in the bhadra in the south, the temple may also be devoted to Shiva.

“Many Shaiva themes are also found in the terracotta panels of the temple. Ganesha takes a prominent place in the bhadra niche in the south. Shiva as Gajasura-samhara-murti appears in one panel. Though the features in this panel are much obliterated, his stretched hands across the panel holding an elephant are very evident. In another panel, Shiva is shown seated with Parvati, probably playing a game of dice,” he wrote. Zaheer counted a total of 143 terracotta panels belonging to the temple: 128 panels in situ, 2 in the Indian Museum, Kolkata, 12 panels in the State Museum, Lucknow, and one panel photographed by Cunningham that is no longer traceable.

The Marvel In Bricks

There is no uniformity about what the temple might have been. Conjectures abound though. About 500 feet from the Bhitargaon Dewal, Cunningham had discovered an old mound of ruins covered with bricks and broken figures which locals called ‘temple of Jhijhi Nag’. He found them to be as ancient as the Dewal and asserted that the temple of Bhitargaon could have been part of a large temple complex which stood back then.

In 2023, when this writer visited the place, nothing about ‘Jhijhi Nag’ was known to the local residents and no trace of any ruins were to be found. Cunnigham had asserted that the temple at Behta, 5 kilometres from Bhitargaon, had pillars taken away from here. This was contradicted by Zaheer based on the architecture of the two temples. According to historians, the iconographical details of the Bhitargaon temple alone put it among the most classical examples of the exquisite temple art. In one panel, Krishna is shown slaying Vrishabhasura and in another, he is subduing Kuvalayapida, the demon elephant. In another panel, he is shown seated with his elder brother Balarama, the latter is shown with a serpent hood above his head. There are images of goddesses Ganga, Yamuna, Parvati seated with Shiva at a game of dice and Durga slaying demons.

The Lone Survivor

A question that has always piqued the historians is how the temple survived so many odds: ravages of time, plunders from locals and roaming marauders of the medieval era and the onslaught of the invaders well over a millennium and a half.

“It seems strange how the Bhitargaon temple with its numerous terracotta sculptures could have escaped the iconoclastic fury of Muhammadan conquerors,” Cunnigham said. He had an interesting theory. He believed the temple was always saved by its remote location.

“Embosomed amid thick groves of trees, and protected by the windings of the Arind river, the temple is so completely hidden, that I failed to descry it even at my second visit until I was within one mile of the village,” Cunningham wrote in 1880. “Perhaps its escape may be solely due to its lucky position. During the great idol-breaking period, when Cawnpore was unknown, and Lucknow was a mere country town, the main lines of road passed by Bhitargaon on all sides at many miles distance,” he wrote.

He believed that the temple could have belonged to a “private individual of special fame”. And its details were unknown to people in larger towns in the vicinity. As a result, it was saved from the prying eyes of the invaders. “Had it been a place of pilgrimage, like Thanesar or Mathura, it would not have escaped the avarice of Mahmud, or the bigotry of Sikandar Lodi,” Cunningham concluded.

' WAS IT A PRIVATE TEMPLE? ‘

Historians also believe that the temple could have belonged to a “private individual of special fame”. And its details were unknown to people in larger towns in the vicinity