Capital punishment: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Capital punishment: incidence of

Actual hangings are rare: Nithari, Rajiv Gandhi cases

From: Dec 18, 2019 Times of India

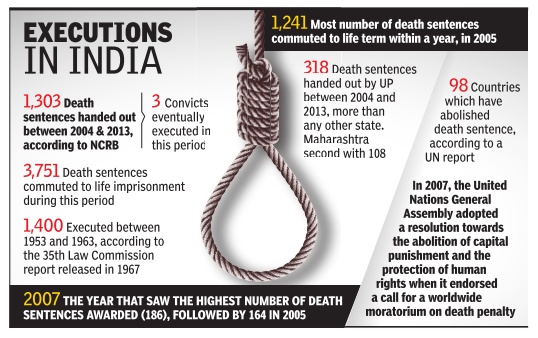

See graphic:

Actual hangings in India are rare as the Nithari and Rajiv Gandhi cases show

Joshi-Abhyankar killings of ’70s Pune

4 Convicts Were Last Hanged In A Day In 1983: Report, Press Trust of India, January 8, 2020: NDTV

In 1983, four convicts in the sensational "Joshi-Abhyankar" killings in Pune were executed together at the Yerwada Central Jail.

Pune:

With four convicts in the Nirbhaya gang rape and murder case set to face the gallows on January 22, this won't be the first time that four convicts on death row will be hanged in a day.

In 1983, four convicts in the sensational "Joshi-Abhyankar" killings in Pune were executed together at the Yerwada Central Jail.

Rajendra Jakkal, Dilip Sutar, Shantaram Kanhoji Jagtap and Munawar Harun Shah were hanged on October 25, 1983.

The Joshi-Abhyankar serial killings were 10 murders committed by them between January 1976 and March 1977.

Suhas Chandak, an accused in the case, had turned an approver.

The murderers were commercial art students at the Abhinav Kala Mahavidyalaya on Pune's Tilak Road. They were notorious for drinking and robbing two-wheelers.

The first murder took place on January 16, 1976.

The victim, Prasad Hedge, was a classmate of the murderers. His father ran a small restaurant behind their college. They sent the note to his father the next day.

Between October 31, 1976 and March 23, 1977 they killed nine more people. They used to break into homes, threaten residents and make them direct the group towards the valuables. They would then murder the family members by stuffing cotton in their mouths and then strangling them with a nylon rope.

The gruesome killings had sent shock waves across Maharashtra.

Sharad Avasthi, who retired as assistant commissioner of police, was present in the court when the death sentence was pronounced.

"I remember that when the accused were sentenced to death, there was a large crowd in the court premises. The four convicts, while being taken out of the court complex after the sentenced was pronounced, were actually waving at the crowd as if they were heroes," he recalled.

Avasthi, who was then a police inspector, said special teams were formed to nab the killers.

"Police officers who had worked in Pune earlier were summoned to investigate the case," he said.

Pune-based social activist Balasaheb Runwal, who was at that time in his teens, said the killings created so much fear among people that they had stopped venturing out of their houses after 6 pm.

"I remember people used to be in a state of shock, but reports related to the killings appearing in newspapers and of the court trials were widely read," he said.

Gujarat, UP have number of prisoners on death row: 2022

Parth.Shastri , Dec 11, 2023: The Times of India

Ahmedabad : At the end of 2021, the Gujarat prisons had eight inmates on the death row of which five were awarded capital punishment or death sentence in the same year. The year 2022 completely changed the picture with the number of inmates on death row shot up to 49 – 41 were awarded the punishment in 2022.

It was the highest single year addition for any Indian state, according to the Prison Statistics India (PSI) report of 2022 by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Uttar Pradesh (30) and Jharkhand (27) were two other states with more than 25 death sentences.

Experts point at the judgement of 2008 serial blasts last year as the primary reason for the phenomenon – 38 of the 49 convicts in the case were awarded death sentences by the judiciary. The inci dent on July 26 had claimed 58 lives in Ahmedabad and was considered one of the biggest terror attacks in India in recent times.

With the update, Gujarat is second across the country with inmates on death row at 49, whereas Uttar Pradesh had the highest 95 such inmates. The report indicated that there was no execution across the country in the calendar year of 2022. The report also highlighted overcrowding and understaffing of state prisons. According to the report, as of December 31, 2022, the state prisons had 16,611 inmates against the capacity of 14,065 indicating 18% more inmates than capacity. The share however was much higher at sub-jails at 39% and central jails at 29%.

Against the sanctioned strength of 3,756 jail officers and personnel, the state had 2,241 or 60% of the present staff. The overall 40% vacancy rate was as high as 57% for the officers from IPS cadre to assistant jailor level. “While some posts were filled up in 2023, efforts are on to reduce the vacancy,” said a senior state official.

At 99, Gujarat had the highest number of undertrials of Pakistan origin. In all, the state had a marked diversity in inmates from other countries — the undertrials included 31 from African nations including Nigeria, 31 from Middle Eastern nations, 15 from Bangladesh, two each from Myanmar and Nepal, and one from Canada.

Commuting death sentence to life imprisonment

Where the age of victims was below 16 years

Nov 9, 2021: The Times of India

Low age of victims in rape-and-murder cases not sufficient for imposing death penalty: SC

NEW DELHI: Low age of victims in rape-and-murder cases has not been considered as the "only or sufficient factor by this court" for imposing the death penalty, the Supreme Court has said referring to its verdict that had analysed 67 similar cases dealt by it in the last 40 years.

The apex court's crucial observation came on an appeal of Irappa Siddappa who was convicted and given death penalty by a trial court. The Karnataka high court confirmed the trial court's decision on March 6, 2017.

He was convicted for kidnapping, rape and murder of a five-year old-girl in the village of Khanapur in Karnataka in 2010 and post the incident, he had put the body of the victim in a bag and thrown it into a stream, named Bennihalla.

A bench comprising Justices L Nageswara Rao, Sanjiv Khanna and BR Gavai confirmed the conviction of Siddappa for offences including rape, murder and destruction of evidence, but set aside the award of death penalty, which was handed down by courts below on grounds including the minor age of the victim, and commuted it to life imprisonment for a period of 30 years.

"We find sufficient mitigating factors to commute the sentence of death imposed by the Sessions Court and confirmed by the High Court into imprisonment for life, with the direction that the appellant shall not be entitled to premature release/remission for the offence under Section 302 (murder) of the Code until he has undergone actual imprisonment for at least thirty years,” said the verdict penned by Justice Khanna for the bench.

It also directed that the sentences shall run concurrently and not consecutively.

The top court extensively dealt with arguments based on minor age of the victims in rape-and-murder cases and referred to the apex court's judgment in the Shatrughna Baban Meshram case in which 67 judgments of the Supreme Court in the previous 40 years were surveyed.

In these judgments, death sentence had been imposed by the trial court or the high court for the alleged offences under Sections 376 (rape) and 302 (murder) of the IPC, and where the age of victims was below 16 years, the apex court said.

"Out of these 67 cases, this Court affirmed the award of death sentence to the accused in 15 cases. In three, ... out of said 15 cases, the death sentence was commuted to life sentence by this Court in review petitions.

“Out of the remaining 12 cases, in two cases..., the death sentence was confirmed by this Court and the review petitions were dismissed. Thus, as on date, the death sentence stands confirmed in 12 out of 67 cases where the principal offences allegedly committed were under Sections 376 and 302 IPC and where the victims were aged about 16 years or below,” it said.

Out of these 67 cases, at least in 51, the victims were aged below 12 years, it said, adding that in three cases, the death penalty was commuted to life sentence in review.

“It appears from the above data that the low age of the victim has not been considered as the only or sufficient factor by this Court for imposing a death sentence. If it were the case, then all, or almost all, 67 cases would have culminated in imposition of sentence of death on the accused,” the top court said.

It referred to various verdicts and said that though such an offence was heinous and required condemnation, it was not “rarest of the rare, so as to require the elimination of the appellant from the society.”

The state government has not shown anything to prove the likelihood that the convict would commit acts of violence as a continuing threat to society, and his conduct in the prison has been described as satisfactory, it said.

"There is no doubt that the appellant has committed an abhorrent crime, and for this we believe that incarceration for life will serve as sufficient punishment and penitence for his actions, in the absence of any material to believe that if allowed to live he poses a grave and serious threat to the society, and the imprisonment for life in our opinion would also ward off any such threat. We believe that there is hope for reformation, rehabilitation, and thus the option of imprisonment for life is certainly not foreclosed and therefore acceptable,” the bench said.

A

AmitAnand Choudhary, Nov 10, 2021: The Times of India

‘Hope for reformation’: SC ‘reprieve’ for rapist-killer

Death Commuted To 30-Yr Jail Term Sans Remission

A man, convicted for raping a five-year old girl and then killing her by strangulation in Gadag district in Karnataka, escaped the gallows with the Supreme Court commuting his death sentence to life imprisonment with a condition that he will spend at least 30 years in jail without remission.

A bench of Justices L Nageswara Rao, Sanjiv Khanna and BR Gavai commuted the death sentence, which was awarded by a trial court and upheld by the high court, after considering his young age at the time of committing the offence, his weak socio-economic background, absence of any criminal antecedents and his satisfactory behaviour in jail in the last ten years, as mitigating factors.

Granting his relief, the Supreme Court said that the high court was wrong in saying that there were no mitigating circumstances at all. “To begin with, it is clear that the appellant had no criminal antecedents, nor was any evidence presented to prove that the commission of the offence was preplanned. As submitted by the counsel for the appellant, there is no material shown by the state to indicate that the appellant cannot be reformed and is a continuing threat to the society,” it said.

Referring to the Supreme Court verdict in Shatrughna Baban Meshram case in which 67 judgments of the apex court in the previous 40 years were surveyed wherein death sentence had been imposed by the trial court or the high court and where the age of victims was below 16 years, the bench said, “It appears from the above data that low age of the victim has not been considered as the only or sufficient factor by this court for imposing a death sentence. If it were the case, then all, or almost all, 67 cases would have culminated in imposition of the sentence of death on the accused.”

Court verdicts

Some famous cases

Famous executioners

Shobita Dhar, Piyush Rai & Sandeep Rai, January 14, 2020: The Times of India

Some sing, some eat a hearty meal and sleep soundly and some go kicking and screaming protesting innocence: Sunil Gupta, retired legal officer at Delhi’s Tihar Jail, has seen the many moods of many a man walking to the gallows. And the grim parade in his 35-year career began one restless night in 1982 when he couldn’t swallow his dinner.

The next morning, January 31, Gupta was to preside over his first hanging — of Billa and Ranga — who were given the death penalty for kidnapping, raping and murdering two teenage siblings in 1978. The case has grisly similarities with the Nirbhaya case in which four men are sentenced to hang later this month: the siblings were given a lift by the two criminals in their car; the 14-year-old brother was struck with a kirpan while his sister was raped and then stabbed.

“Until then, I had only read about Billa and Ranga in newspapers. When I first saw them, it was something else,” says Gupta who recounts the night in his book, Black Warrant, which he co-wrote with journalist Sunetra Choudhury. Prisoners are told a week ahead of their hanging so they may speak to family and friends and settle their will. “The jail superintendent has to convey this information,” says Gupta. “While Ranga was a happy-go-lucky fellow who would always say ‘Ranga khush (happy)’, Billa was always weeping and blamed Ranga for the crime and the death sentence.” The prisoner is moved to the death cell — jail number 3 — and put on suicide watch. All belongings are taken away, even the pyjama string as it can be used to strangle oneself. Then, sheer mechanics take over. The prisoner is weighed, his height and length of the neck measured to prepare the equipment for the execution. “The heavier the prisoner, the shorter the fall. It’s very important to follow the procedure because otherwise there’s a risk of decapitation,” says Gupta. The hanging is then simulated with sandbags 1.5 times the convict’s weight just to make sure the noose is strong enough. In his book, Gupta says wax or butter is applied to ensure the rope doesn’t cut; some hangmen like Bengal’s Nata Mullick preferred soap and mashed bananas instead. “The night before their hanging, Ranga ate his meal and slept well but Billa kept pacing his cell, muttering. When they were hanged, Billa was sobbing but Ranga went shouting Jo Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal ,” remembers Gupta.

While the SP usually nods at the hangman to pull the lever, to hang Billa and Ranga, he chose to signal with a dramatic wave of a red handkerchief. The ‘Billa-Ranga’ hanky remained a souvenir he would show friends and relatives.

The hanging had a hair-raising moment too. When the jail doctor went to check on Ranga two hours after the hanging as per rules, his pulse was still going steady. “Sometimes, the prisoner stops breathing due to fear and the air stays trapped in the body. This is what must have happened in his case,” says Gupta, recalling that a guard was then asked to jump into the 15-feet-deep well over which Ranga was hanging and pull his leg. “That released the trapped air and the pulse stopped.”

Having witnessed eight hangings in his career, Gupta has come to be realistic about a job that must be done. He often breaks into a hearty guffaw as he narrates his interactions with the death row convicts — hardened criminals shorn of their reputations, only men keenly aware of the end.

The night before their hanging, Ranga ate his meal and slept well but Billa kept pacing his cell, muttering. When they were hanged, Billa was sobbing but Ranga went shouting Jo Bole So Nihal, Sat Sri Akal Sunil Gupta, Retd legal officer at Delhi's Tihar jail

Gupta remembers that Maqbool Bhat, founder of Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front who was hanged in 1984, helped him improve his English. Bhat served his death sentence in Tihar for the murder of a government official. “He was an educated and pious man and spoke fluent English. The jail staff often got him to file replies to official memos,” says Gupta.

Bhat’s black warrant came suddenly, after the kidnapping and murder of Indian diplomat Ravindra Mhatre in UK by a separatist group that had demanded Bhat’s release. “On the day of his hanging, Bhat was calm and composed.” He (Maqbool Bhat) was an educated and pious man and spoke fluent English. The jail staff often got him to file replies to official memos Sunil Gupta, Retd legal officer at Delhi's Tihar Jail

Contrary to the cliché in films, there is no last wish ritual, says Gupta. “What will prisoners ask for? They say don’t hang us or give us a non-vegetarian meal. Neither can be granted. Tihar is a vegetarian prison,” he says.

The last hanging that Gupta witnessed impacted him the most. The hardened officer admits he became quite emotional about Mohammad Afzal Guru, who was given the death sentence for his role in the Parliament attack of 2001.

Before going to the phansi kothi, the SP, Afzal and I sat down to have tea on the morning of Feb 9, 2013. He discussed his case and said he was not a terrorist, just an ordinary man fighting the system. Then he sang a song from an old Bollywood film, Badal: Apne liye jiye toh kya jiye, tu ji ae dil zamane ke liye Sunil Gupta, Retd legal officer at Delhi’s Tihar Jail

“Before going to the phansi kothi (jail number 3, ward 8), the SP, Afzal and I sat down to have tea on the morning of February 9, 2013. He discussed his case and said he was not a terrorist, just an ordinary man fighting the system. Then he sang a song from an old Bollywood film, Badal: Apne liye jiye toh kya jiye, tu ji ae dil zamane ke liye ,” recalls Gupta. In his book, Gupta says there was something so moving in the way Afzal sang that Gupta joined him. It’s a song Gupta says he has heard more than 100 times since.

Details

Rope Ready

- Length of the rope = Length of the drop + the distance from the angle of the prisoner’s jaw to the ring

- The noose is made from Manila rope manufactured in Bihar's Buxar jail. The jail is located next to the Ganga river and has a humid climate, which ensures the rope fibres are strong yet soft. If fibres are rough, they can decapitate the convict

- Hangmen prepare the rope by rubbing it with wax or butter. Some even use mashed bananas

- Two spare ropes per convict are kept in reserve, ready on the scaffold, in case of a mishap while carrying out the execution

Morning Hanging

All hangings are to be carried out early in the morning before it gets too bright, with the convict's hands tied behind his back. No execution can take place on a public holiday

A Piece Of Gallows For Curing Exam Fear

Sunil Gupta says a lot of people believe that keeping a piece of wood taken from the wooden planks can remove fear from a child. "We used to get a lot of requests for this wood," he recalls.

Shunned By Society

Janardhan Pillai

Count: 117

He was the hangman of the King of Travancore in 1940s. Shashi Warrier wrote a fictional account of Pillai’s life in a book titled ‘The Last Hangman’. It shows Pillai as a serious and withdrawn man who faced social ostracisation because of his work.

Old Monk For Hangman, Convict

Nata Mullick

Count: 25

Most well-known execution: Dhananjay Chatterjee, who raped and murdered a teen

Mullick was said to drink heavily before executions so that he wouldn’t flinch while pulling the lever. As Bengal’s state executioner, he got Rs 150 and a bottle of Old Monk every time he left a prisoner hanging on the gallows. In his book, Black Warrant, Sunil Gupta writes that Mullick would pour some of that rum onto the hanging plank after pulling the lever as an offering to the escaping soul of the prisoner. He died in 2009

Deadly Duo

Kalu & Fakira

Most well-known executions: Indira Gandhi’s assassins

The two worked as a pair. If one developed cold feet, the other was there to do the deed, writes Gupta. Kalu worked in Meerut jail while Fakira at Faridkot jail

Last Wish

Mammu Singh

Count: 15

Kalu trained his son, Mammu, who would send flyers — ‘Expert hangman. Rent his services’ — to Tihar and other jails to get work. But Mammu was never hired at Tihar because he was not a government employee, Gupta notes in his book. Mammu went on to be the hangman at Meerut jail. But his desire to execute Kasab remained unfulfilled. Now, son Pawan Kumar, carries the family legacy forward

One Of India’s Last Jallads On A Dying Biz

Soon after the death of UP’s official hangman, Pawan Kumar decided to step into his father Mammu Singh’s shoes. In 2013, the UP Directorate of Prisons took him on a retainership but six years later, the fourth generation ‘jallad’ is still waiting with the noose.

There was one near-call — in 2014, he was scheduled to hang the notorious Surinder Koli but the prisoner got a judicial reprieve. “For seven days, I strenuously prepared for the execution. But he got away,” says Kumar, sounding almost disappointed.

Now, with Tihar jail asking the UP prison department for hangmen to execute the four Nirbhaya convicts, the 57-year-old has his hopes up. Though he’s currently enjoying the attention of TV crews buzzing around him for bytes, it’s not the momentary fame or the paltry stipend of Rs 3,000 a month that attracts him. His motivation, he says, stems from his sense that justice needs to be done. “I kill people who have committed the most heinous of crimes. In fact, I am cleansing the world of its evil. So, I respect my profession,” he told TOI last month.

He also feels he will get a chance to redeem his family’s honour. Kumar’s great grandfather Laxman Ram served the British Raj and hanged several freedom fighters — a fact that bothered his grandfather Kallu Jallad and father Mammu Jallad — who were also hangmen. Kumar, too, doesn’t like to talk about his great grandfather.

“My father Mammu Singh wanted to hang 26/11 attack convict Ajmal Kasab and Parliament attack convict Afzal Guru to wash away the blot of freedom fighters’ blood on our family’s reputation,” Kumar said. Singh, however, passed away in May 2011, a year before Kasab was sent to the gallows.

Though other executions have happened – Afzal Guru in 2013 and Yakub Memon in 2015 – they have been handled by prison constables whose identities have been kept anonymous.

One reason for this is that almost no state now has a hangman. In fact, the only other professional hangman is an ageing Ahmadullah, who lives in Lucknow and is currently unwell. Though the only qualifications are that one has to be an adult male with a minimum height of five feet four inches, there are very few — quite understandably — who have the stomach for it.

Kumar, who lives with his family in a one-bedroom house at Kanshi Ram Awas Yojana in Lohia Nagar and sells clothes from a pushcart for a living, Meerut, says his children are unlikely to take up his profession. “My father Mammu was the state hangman for 47 years till he died on May 19, 2011, but the government has offered little in lieu of the services provided by our family. We get a stipend but no government job and no security. This legacy will probably die with me,” he says.

Analysis of capital punishment cases

2016> 19

Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

From: Feb 3, 2020: The Times of India

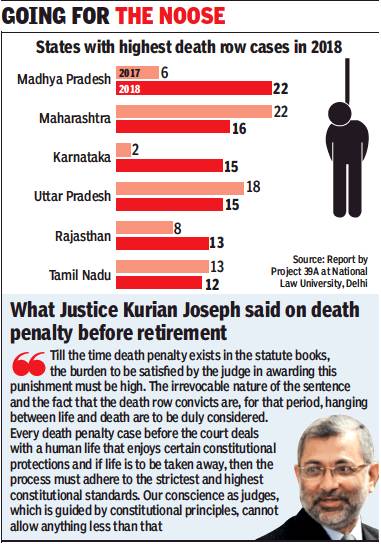

NEW DELHI: Even as the hanging of convicts in the Nirbhaya gang rape and murder case is put on hold, TOI takes a look at how the courts dealt with death sentences in 2019.

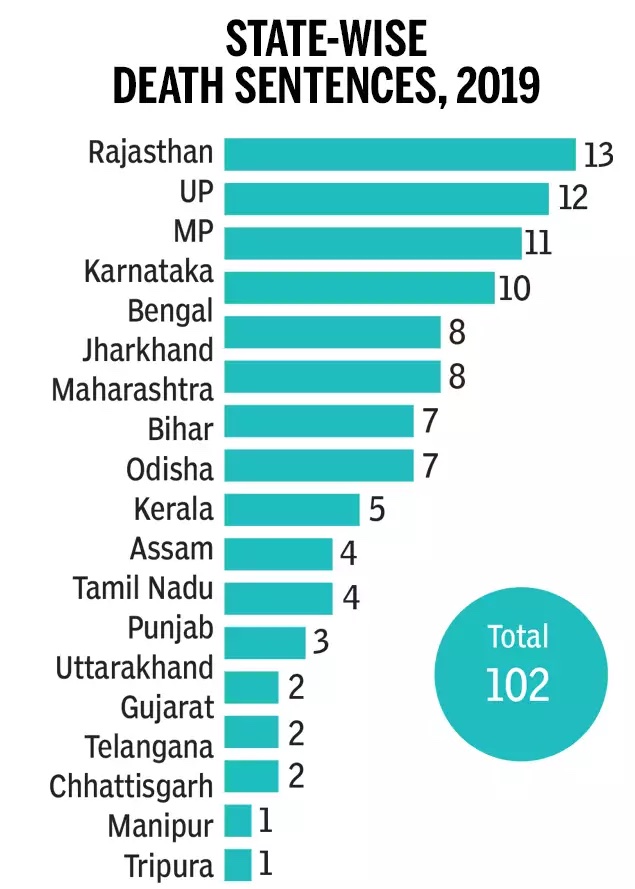

102 death sentences in 2019, Rajasthan handed out the most

Over the years, death sentences handed out by the courts have declined. Last year, sessions courts across the country handed out a total of 102 death sentences -- the lowest in four years. Barring Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim, all other states handed out the death penalty in 2019. Rajasthan sentenced the maximum number of people to hang, followed by Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka.

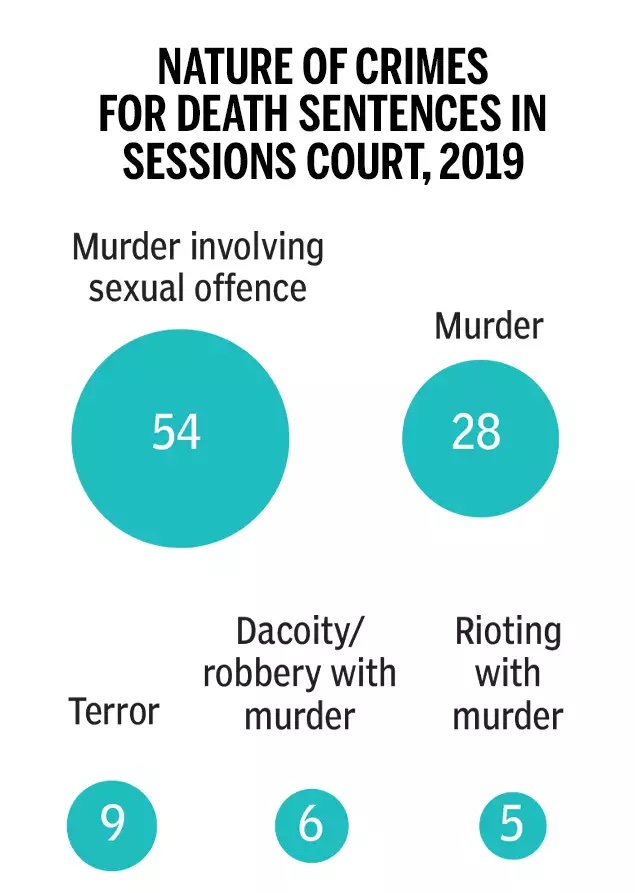

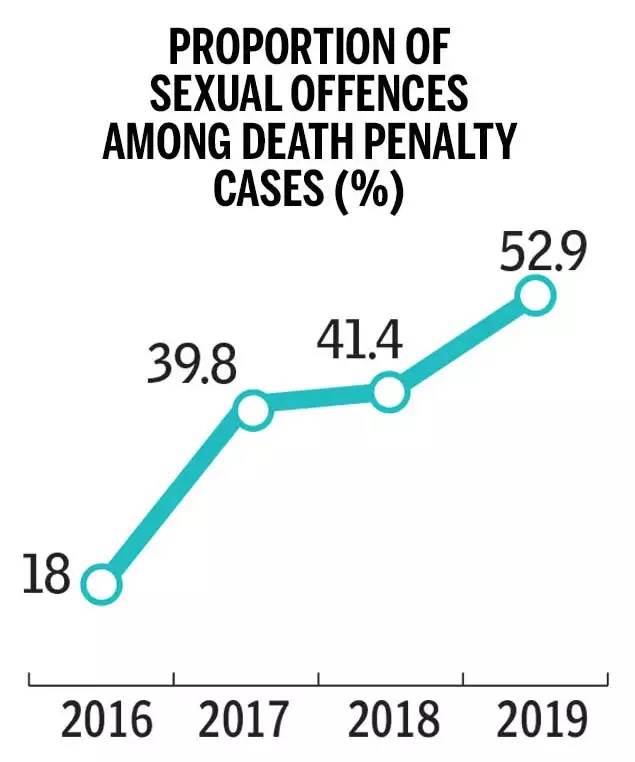

Most death sentences are for murders involving sexual crimes But while the total number of death sentences has fallen, the proportion of cases of murder involving sexual offences has gone up, from 18% in 2016 to 52.94% in 2019. This could be due to an amendment to the POCSO Act 2012, which introduced stringent mandatory minimum punishments and the death penalty for penetrative sexual assault on children.

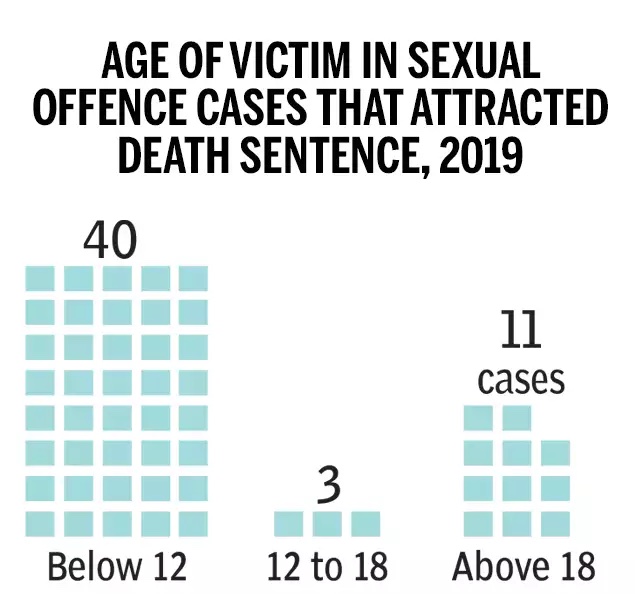

Disturbingly, in most cases, the youngest were the most vulnerable. In 2019, 39.21% of the total death sentences (40 out of 102) were cases of murder involving sexual offences with victims below 12 years of age.

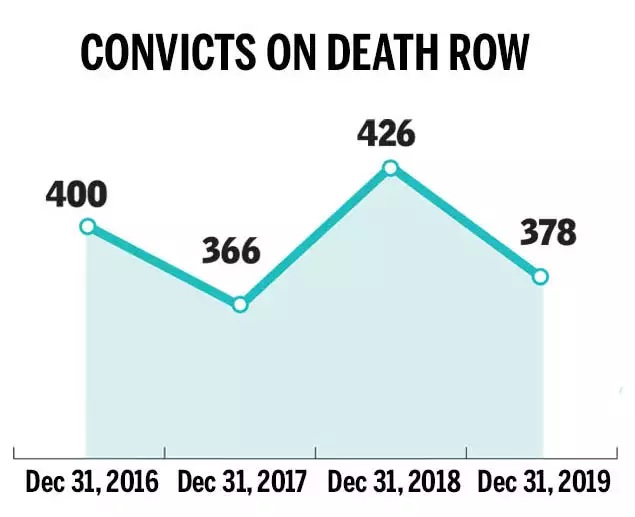

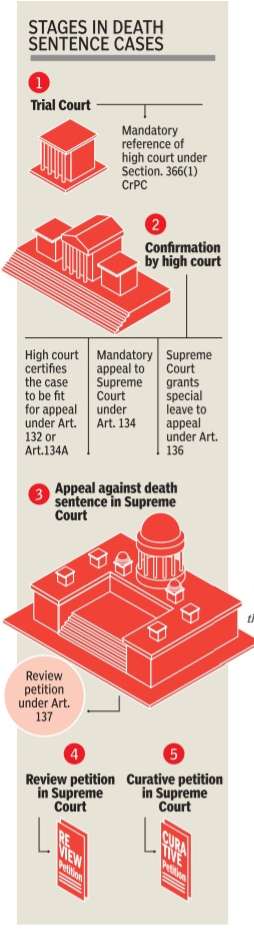

With few executions, 378 convicts still on death row Executions, however, have not been quick despite strict laws and session courts imposing death sentences. As of December 31, 2019, there were a total of 378 convicts were on death row. This is because after a trial court hands out the death sentence, convicts still have two chances to appeal the decision — in the high court and Supreme Court. If the death sentence is upheld by the higher court, the convict can seek a pardon from the President or state governor in some cases.

Uttar Pradesh has the most number of convicts on death row, followed by Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh. In fact, UP and Maharashtra house nearly a quarter of all death row convicts — 54 and 45 respectively. Madhya Pradesh has 34.

For murder involving sexual offences, more sentences commuted than confirmed .

In 2019, high courts commuted only 26.8% (15 out of 56) of death sentences for murder involving sexual offences, while confirming 65.4% (17 out of 26) — the highest in four years.

In contrast, 64.7% (11 out of 17) of the death sentences commuted by the Supreme Court were cases of murder involving sexual offences. 57.1% (4 out of 7) of the SC’s confirmations were cases of murder involving sexual offences.

UP, Rajasthan and Maharashtra high courts handed out the most commutations. Maharashtra and Haryana high courts confirmed the most death sentences.

2000-2015

Capital punishment orders of courts in 3 Indian states, 2000-2015

Himanshi Dhawan, May 14, 2020: The Times of India

From: Himanshi Dhawan, May 14, 2020: The Times of India

Almost half the death penalty judgments given by criminal courts in three states were done so on the date of conviction, according to a report by the National Law University, Delhi’s Project 39A which looked at 215 capital punishment orders awarded between 2000-2015 by courts in Delhi, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh.

The report expressed concern over this haste in sentencing. “In MP, same-day sentencing was observed in 76.9% of the cases. Maharashtra had same-day sentencing in 34.4% of the cases, but 57% of the cases had sentencing either on the same day or with just a 24-hour gap. Delhi fared relatively better with 53.4% of sentencing hearings taking place at least one week after the conviction,” the report said.

About 322 prisoners across the three states were sentenced to death of which nearly half or 49% of the prisoners were found guilty of murder while 28% had the death penalty imposed for murder involving sexual offences.

The three states were chosen because the death penalty was frequently imposed and a large number of the decisions in capital cases were overturned at appellate level. The report also found that death penalty in India is imposed in a manner that is subjective, arbitrary and does not adhere to the “rarest of rare” principle. “We found that this principle, mandated to be used for death penalty, is an empty doctrine,” Anup Surendranath, 39A executive director, said.

Life imprisonment was not even considered in many cases. According to section 354(3) of the CrPC, life imprisonment is the default option and the death sentence requires special reasons. Instead, courts have considered life imprisonment only in eight out of 43 in Delhi, 22 of 82 in MP, 27 of 90 in Maharashtra.

The courts appeared to have given more importance to brutality of the crime and lack of remorse rather than to mitigating circumstances like socio-economic conditions of the accused, age, or the circumstances that led to the crime. The inadequate nature of arguments made by defence lawyers had an impact on the courts’ not even considering mitigating factors during sentencing. The trial courts mainly relied on aggravating circumstances to impose death sentences. The MP trial courts’ reliance only on aggravating factors to impose death sentence was particularly high.

In as many as 51 judgments out of a total of 82 in MP, no mitigating circumstances were considered during sentencing while 41 out of 90 cases from Maharashtra adopted this approach. In Delhi, in 18 out of a total of 43 cases, the decision did not include consideration of mitigating factors.

Death penalty not open-ended, must have finality: SC

Dhananjay Mahapatra, January 24, 2020: The Times of India

NEW DELHI: Revealing judicial discomfort over death row convicts exploiting procedural loopholes to avoid or delay execution for years, the Supreme Court on Thursday said “it is extremely important for death penalty to attain finality”.

Indirectly referring to continuous and separate litigations by the four Nirbhaya case condemned prisoners to delay execution, a bench of Chief Justice S A Bobde and Justices S Abdul Nazeer and Sanjiv Khanna said, “Many are under the impression that concurrently awarded death penalty (by trial court, high court and the SC) is open-ended and can be argued against as and when one wishes. Finality of death sentence is extremely important. Recent events have shown that. One cannot go on fighting endlessly on this.”

The court also held that post-conviction “good behaviour” in jail may not be sufficient to modify a death sentence as any mitigating circumstances are taken into account by courts at the trial stage. While the court was not against reformation, punishment reflected societal expectation and gravity of crime, the bench said.

The CJI-led bench’s observations came during open court hearing of petitions by one Shabnam and Saleem seeking review of their death sentences. Infuriated by constant objections to their relationship, which had resulted in pregnancy at the time of the crime, Shabnam mixed sedatives in tea and served it to her family members. She then held the heads of her parents and four other family members while Saleem slit their throats. A seventh victim, her brother’s 10-month-old child, was throttled to death. The duo wanted to lay claim over the entire family property.

The bench’s remarks assume significance as the Centre on Wednesday, responding to public resentment over Nirbhaya convicts delaying execution, sought a change in guidelines laid down by the SC in 2014 to protect the rights of death row prisoners. The Centre said the rights of victims and society must also be factored in. When solicitor general Tushar Mehta mentioned this during Thursday’s hearing, the SC said it would separately deal with it.

For Saleem and Shabnam, senior advocates Anand Grover and Meenakshi Arora strenuously attempted to convince the bench that the couple’s exemplary post-conviction conduct should be considered for commuting the death penalty to life imprisonment. Arora said as the couple now had a child to look after the court could exercise forgiveness as they had shown enough signs of reform during incarceration.

The bench asked, “Does the couple having a child mitigate the gravity of their crime? Does it mitigate the murder of a 10-month-old child? Does that mitigate the murder of seven innocent family members? We are not against forgiveness. But it is the law which prescribes punishment for crime. A judge awards punishment as per law, which reflects society’s expectations. We must protect innocent and also punish the guilty. Can a judge forgive a murderer brushing aside evidence if he feels an accused appears innocent?” Responding to mitigating circumstances cited by Grover and Arora, the bench said, “A court examines mitigating circumstances at the time of sentencing. Can post-conviction mitigating circumstances be a ground for commuting death sentence? What we understand is that the sentence should be proportionate to the crime. Seven members of a family were killed through meticulous planning and in cold blood. Is the death sentence proportionate to this crime? All three courts have said yes.

“If post-conviction good behaviour is accepted as mitigating circumstances, then there never will be finality to sentences and it will open the floodgates for petitions seeking commutation of all kinds of sentences.”

The bench then reserved its verdict on the review petitions.

HC says, execution delay against rights, commutes death

Shibu Thomas, July 30, 2019: The Times of India

The Bombay high court commuted the death penalty given to two convicts in the 2007 Pune BPO employee rape and murder case to life imprisonment of 35 years, citing the “inordinate and unreasonable” delay in executing them.

A division bench of Justices Bhushan Dharmadhikari and Swapna Joshi said the 35-year jail term would include the time they have already spent in jail.

Purushottam Borate (38) and Pradeep Kokade (32), who were due to be executed on June 24, 2019, had approached the high court through their lawyer Yug Chaudhry. The duo were sentenced to death for raping and murdering a 22-year-old woman employee of a BPO company in Pune.

2016-19: criminals guilty of sexual violence more likely to hang

Himanshi Dhawan, May 14, 2020: The Times of India

A criminal found guilty of sexual violence is more likely to hang now than four years earlier as trial courts in some states have an increasing propensity to award death for such crimes, suggests a report.

In 2016, MP awarded death in 33.3% of such cases; this rose to 81.8% in 2019. Similarly, in Maharashtra, 45.5% of such cases were awarded capital punishment four years ago which rose to 71.4% in 2019. The data on the two states was collated by NLU, Delhi’s Project 39A, which studies death penalty cases in India. Project 39A executive director and NLU assistant professor Arup Surendranath said, “In the post-Nirbhaya context, social and political conversations have been inclined towards harsher punishment as a means to address the growing concern over such cases.”

2018-20: analysis of court verdicts

Himanshi Dhawan, Oct 23, 2022: The Times of India

From: Himanshi Dhawan, Oct 23, 2022: The Times of India

There is a popular maxim — justice delayed is justice denied. But what happens when judgments are given in haste? In a majority of cases related to minor’s rape or murderrape of minors, trial courts have convicted and sentenced the accused within a few days, a report has revealed.

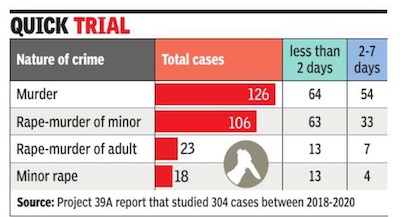

Of the 18 cases of minor rape where death penalty was imposed, in 13 (72%) of the cases, trial courts took fewer than two days to decide on conviction and sentencing while the remaining four cases were decided within a week. Minor-rape murder cases went in a similar vein. In a total of 106 such cases, in 63 or about 60% cases, trial courts took the decision of holding the person guilty and sentencing them to death penalty in less than two days. In 33 cases, the process was completed within a week.

National Law University Delhi’s Project 39A analysed 304 death sentences across 221 cases in its report ‘Death penalty sentencing in India’s trial courts 2018-2020’.

Of the death sentences analysed, there were 125 cases of murder-rape of a minor and minor rape. In these 15% of the cases were decided in less than a week while 28% cases were decided in less than 3 months. This data calls into question sentencing practices in lower courts and is an analysis of the 2019 amendments to the Protection of Children Against Sexual Offences (Pocso) act that introduced the death penalty provision as punishment for those found guilty of aggravated penetrative sexual assault of a minor. In cases of murder or rapemurder of an adult, the courts took a two-day period to impose death penalty in half the cases. For instance, of the total 23 cases of murder involving sexual violence with an adult, 13 (56%) ofthe cases were decided within two days while of the total 126 murder cases, the courts imposed death penalty in less than two days in 64 or 50% of the cases.

According to report co-author Zeba Sikora, the short gap is an indication of the mechanical manner in which people are sentenced to death. “Little or no time between these two phases of a trial means that the accused person’s legal team has not been given sufficient time to present mitigating circumstances relating to the accused.

While this is a problemacross the board in death penalty cases, data from trial courts shows that the problem is more acute in cases involving sexual offences against children. Simply put, this means that many people and more so, persons convicted for sexual crimes against children, are sentenced to death without being given the opportunity for an effective sentencing hearing,” Sikora said.

The report also points out that judges dismissed the alternative of life imprisonment and sentenced the convicted to death ‘by default’ in nearly 30% of the sentences involving minor rape.

Reasons for this haste range from public pressure after a heinous crime, as well as more scrutiny of the judicial process because of the frenzy around it. The report shows that this scrutiny might be adversely affecting the convicted and the judicial system.

Earlier, research by Project 39A had revealed that fewer than 5% of the death sentences imposed by trial courts between 2000-15 were confirmed up the judicial ladder, and around 30% ended in acquittals upon appeal which indicates that decisions on levying capital punishment might be taken under pressure.

Sikora was optimistic as issues of death penalty sentencing have been referred to a Constitution Bench.

Death only when life term inadequate: SC/ 2019

AmitAnand Choudhary, March 13, 2019: The Times of India

Holding that the death sentence should be awarded for heinous crimes only when life imprisonment appears to be wholly inadequate, the Supreme Court on Tuesday spared a man from the gallows and sentenced him to 25 years in jail for raping and killing a minor girl in 2015.

A bench of Justices N V Ramana, M M Shantanagoudar and Indira Banerjee convicted a school bus driver who had raped and murdered the child in Jabalpur and refused to give credence to some discrepancies in the statement of witnesses. It said traditional dogmatic hypertechnical approach has to be replaced by a rational, realistic and genuine approach for administering justice in a criminal trial.

The accused had taken the ground that there were procedural lapses on the part of police and his alleged confession, which led to the recovery of the victim’s body, was liable to be rejected as the panchnama was drawn at the police station and not at the spot from where the body was recovered. He said the prosecution’s case mainly rests on the last-seen circumstances, but the said circumstance has not been duly proved.

SC: Benefit of doubt must not be fanciful

The court, however, rejected his plea and said there was sufficient evidence to prove his guilt and upheld the trial court and HC’s order of conviction. But the bench commuted the punishment to 25 years’ imprisonment without remission. “As has been well-settled, life imprisonment is the rule to which the death penalty is the exception. The death sentence must be imposed only when life imprisonment appears to be an altogether inappropriate punishment having regard to the relevant facts and circumstances of the crime,” the bench said.

Rejecting the plea of the accused for granting him the benefit of the doubt, the bench said courts are not obliged to make efforts either to give latitude to the prosecution or loosely construe the law in favour of the accused.

“In our considered opinion, all the circumstances relied upon by the prosecution are proved beyond reasonable doubt and consequently the chain of circumstances is so complete so as to not leave any doubt in the mind of the court that it is the accused and accused alone who committed the offence in question. It is worth reiterating that though certain discrepancies in the evidence and procedural lapses have been brought on the record, the same would not warrant giving the benefit of the doubt to the accused/appellant. It must be remembered that justice cannot be made sterile by exaggerated adherence to the rule of proof, inasmuch as the benefit of doubt given to an accused must always be reasonable, and not fanciful,” the bench said.

Ghastly nature of crime not sole criterion for giving death: SC

February 10, 2022: The Times of India

Ghastly nature of crime not sole criterion for giving death: SC

New Delhi: Holding that the abhorrent nature of a crime can’t be the sole and decisive factor for awarding the death sentence, the Supreme Court said the possibility of an offender reforming and his socio-economic background and other mitigating factors can’t be ignored while awarding the sentence.

It commuted the capital punishment awarded to a convict to 30-year jail in a rapecum-murder case of a sevenyear-old girl in UP, reports Amit Anand Choudhary.

A bench of Justices A M Khanwilkar, Dinesh Maheshwari and C T Ravikumar said that the abhorrent nature of the crime and its repulsive impact on society also cannot be ignored while sentencing.

Nature of crime and impact on society can’t be ignored: SC

The SC said abhorrent nature of the crime and its repulsive impact on society also cannot be ignored while sentencing and in such cases, the sentence of life imprisonment be awarded without application of provisions of premature release/remission for a substantial length of time as has been done by the apex court in several cases. “It could readily be seen that while this court has found it justified to have capital punishment on the statute to serve as deterrent as also in due response to society’s call for appropriate punishment in appropriate cases but at the same time, the principles of penology have evolved to balance the other obligations of society, i.e., of preserving the human life, be it of accused, unless termination thereof is inevitable and is to serve the other societal causes and collective conscience of society,” Justice Maheshwarisaid.

The SC said the delicate balance expected of the judicial process has led to another midway approach, in curtailing the rights of remission or premature release while awarding imprisonment for life, particularly when dealing with crimes of heinous nature. The bench disapproved the trial court and the Allahabad HC for awarding death sentence on the basis of the nature of crime and not taking into consideration mitigating factors like the offender had no criminal antecedent.

Crime and capital punishment

Rape- murder and capital punishment

Rape and murder of 23 year-old paramedic Nirbhaya on December 16, 2012 had sparked unprecedented national outrage.Deep internal wounds caused by wolves of lust snuffed out her life 13 days later in Singapore, where she was shifted for emergency treatment.

The Supreme Court termed the crime “brutal, barbaric and diabolic“ to award death penalty to all four adult accused. Thunderous applause followed the unanimous decision of Justices Dipak Misra, R Banumathi and Ashok Bhushan. Members of society , who had defied prohibitory orders on cold December nights of 2012 to hold candle-light marches in the capital, clapped in approval.

Did the SC show similar sensitivity in the last two decades for society's cry for justice in even more shocking rape-cum-murder cases involving extreme brutality?

What separated the Nirbhaya case from these, which happened away from cities, was the absence of public outrage and candle-light marches.

In the hinterland, life continues to be cheap, that of a girl child even cheaper.Rape and murder of a girl is blamed more on her destiny than the accused. Daily struggle for livelihood quickly douses the outrage, and candles are far too costly to buy and burn for the cause of a dead girl.

Is award of death penalty dependent on an individual judge's sensitivity and volatility of his judicial conscience?

In February 1999, a bench of Justices G B Pattanaik and S Rajendra Babu commuted death penalty to life sentence for Akhtar, who was concurrently awarded death penalty by the trial court and Allahabad HC for raping and murdering a minor girl. The logic, “The accused has committed murder of the girl neither intentionally nor with pre-meditation. The accused found a young girl alone in a lonely place, picked her up for com mitting rape; while committing rape and in the process by gagging, the girl had died. It cannot be categorised as `rarest of rare' case to justify imposition of death penalty .“

In December 1999, an SC bench of Justices G T Nanavati and K T Thomas in Maharashtra vs Suresh found the man guilty of kidnapping a four-year-old girl, sexually assaulting her and then murdering her. The trial court had awarded him death penalty .But the HC acquitted him.The SC said the HC had gravely erred by ignoring material evidence. But it commuted death sentence to life imprisonment saying the man was acquitted, even though erroneously , by the HC.

In October 2001, in Bantu vs Madhya Pradesh, Justices R C Lahoti and Ashok Bhan awarded life sentence to a man found guilty of raping and murdering an 11-year-old girl. After murdering her, he had chopped off her ankles with an axe to take her silver anklets. The parents discovered her body and severed limbs in the fields.

In Sebastian vs Kerala, Justices H S Bedi and J M Panchal in October 2009 commuted death sentence to life imprisonment for a man who had kidnapped a two-year-old child, raped her and then murdered her brutally . Despite recording that the man was a known paedophile, the SC said imprisonment for entire life was just punishment.

In September 2013, Justices C K Prasad and Kurian Joseph in Rajasthan vs Jamil Khan found a man guilty of brutally raping and killing a five-year-old. He had packed the body in a gunny bag and left it in a train. Commuting the trial court's decision to impose death penalty, the SC awarded 24 years jail term to him.

In February 2014, Justices B S Chauhan and M Y Eqbal found a man guilty of raping a friend's daughter and murdering her by strangulation.The girl used to call the rapist `uncle'. The SC set aside the concurrent decisions of the trial court and the HC to award death sentence and replaced it with 35 years jail term. It said, “We are of the view that in spite of the fact that the appellant has committed a heinous crime and raped an innocent, helpless and defenseless minor girl who was in his custody , he is liable to be punished severely, but it is not a case which falls within the category of `rarest of rare’.“

Apparent lack of uniformity in awarding sentences, even in gruesome murder cases, was discussed by the SC in November 2012 in Sangeet vs State of Haryana. “In the sentencing process, both the crime and the criminal are equally important. We have, unfortunately , not taken the sentencing process as seriously as it should be with the result that in capital offences, it has become judgecentric sentencing rather than principled sentencing,“ it had said.

It said the Bachan Singh case (1980), contrary to popular perception, did not endorse the principle of aggravating and mitigating circumstances to weigh imposition of capital punishment. “ Aggravating circumstances relate to crime while mitigating circumstances relate to criminal. A balance-sheet cannot be drawn up for comparing the two. The considerations for both are distinct and unrelated. The use of the mantra of aggravating and mitigating circumstances needs a review,“ it had said. We hope the Nirbhaya judgment will make the SC take a relook at the nuances of sentencing so as to inject uniformity .

Safeguards introduced by Supreme Court rulings

February 1, 2020: The Times of India

From: February 1, 2020: The Times of India

A trial court’s decision to postpone, “till further orders”, the execution of the Nirbhaya convicts underlines how safeguards introduced by Supreme Court rulings expanding death penalty jurisprudence can be exploited. The dilly dallying by Tihar administration, experts say, is by no means any less responsible for the delay.

As far back as 1982, the apex court had acted to prevent “judicial vagaries” in imposing death sentence. In the Harbans Singh vs State of UP case, the court ruled that till the time the convicts exhausted all their legal options, none would be hanged. The court inserted the protection after it emerged in this case that one convict was executed, but a second person was awarded life imprisonment even as the third was set to be hanged.

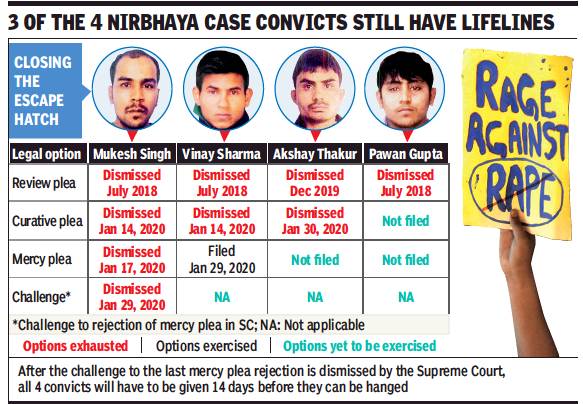

This ruling is reflected in Delhi’s revised jail manual as Rule 854, and was cited by the convicts’ lawyers on Saturday in the trial court, which postponed their execution indefinitely, giving the condemned prisoners a reprieve for the second time in two weeks. Going by the strategic manner in which the four men have exploited loopholes to file mercy, curative and review pleas in close succession, such dilatory tactics may well push the date of execution to March or beyond, since two of the men are yet to file a mercy plea.

This is for the second time that the execution of the death warrants has been deferred. The first order, issued on January 7 for January 22, was stayed on January 17. The second warrant, issued on January 17, for February 1, was stayed.

A 2014 ruling by Supreme Court on capital punishment in the Shatrughan Chauhan vs Union of India case also figures as a major factor in deferment of the death warrant. It provides a 14-day window to a condemned person to make “peace with God” and accept his fate, after the rejection of mercy by President. In Mukesh Singh’s case, President Ram Nath Kovind rejected his mercy plea on January 17, well before the scheduled hanging date of January 22. Yet, the Tihar administration expressed its helplessness in carrying out the sentence as that would have breached SC’s mandate.

There is, however, merit in the allegations that the jail administration failed to act quickly in July 2018, once Supreme Court dismissed the review plea of three convicts. With the judicial process having got over, experts said that it was when the jail and the trial court concerned could have gone ahead and issued a death warrant. “The process of availing the remedies would have started after July 2018 itself. The prosecution sat for almost two years in carrying out a sentence confirmed by all levels of the judicial hierarchy. There is no rule that says that a death warrant can’t be issued before filing of the mercy plea. After all, the situation remained unchanged between July 2018 and January 7 this year,” a senior judge said. Interestingly, the jail administration changed its stance on Saturday and challenged the application for a stay, arguing that the death-row convicts could be hanged separately. Earlier, before Delhi high court, it had conceded that the rules forbade separate execution of the convicts sentenced to death in the same case.

The trial court, however, rejected this argument and partially agreed with advocate AP Singh, the counsel for the three convicts — Pawan, Vinay and Akshay — that their legal remedies were yet to be exhausted.

Constitutional and legal remedies available

Redress of grievances through procedure established by law is the hallmark of any civilised society, said a Delhi court on Friday and “postponed till further orders” hanging of the four convicts in the 2012 Nirbhaya case.

Additional sessions judge Dharmendra Rana stated, “The courts of this country cannot afford to adversely discriminate against any convict, including death row convicts, in pursuit of his legal remedies by turning a Nelson’s eye towards him.”

Special prosecutor Irfan Ahmed said that Mukesh had exhausted all his constitutional and legal remedies and the mercy plea of another convict Vinay Kumar Sharma was pending. In case of the other two, Pawan and Akshay, there weren’t any pleas pending. The state prosecutor, therefore, said that barring Vinay, the other three men could be hanged on February 1.

Trial court cites prison rules, says 3 convicts can’t be hanged separately

Ahmed submitted that any relief to the three convicts apart from Sharma was tantamount to abuse of the process of law and lead to travesty of justice.

The court, however, dealt with the prosecution’s contention stating that Rule 836 of the Delhi Prison Rules provided that if an appeal or an application is made by only one convict, the execution of sentence shall be postponed in the case of co-convicts. Appearing for the three convicts — Sharma, Gupta and Thakur — advocate A P Singh argued that while Sharma’s mercy plea had been filed, convict Thakur intended to file a mercy plea before the President of India.

Amicus curiae Vrinda Grover and advocate Soutik Banerjee, who appeared for convict Mukesh, submitted that the convict had been “earnestly” and “sincerely” pursuing his legal remedies without any unnecessary delay.

Grover stressed that since all convicts were held guilty for the same offence and were convicted by a common judgment their fate could not be segregated and convict Mukesh’s case couldn’t be dealt with separately.

Grover relied on a precedent of the Supreme Court in the matter of Harbans Singh versus the state of UP to contend that the execution of the death sentence would lead to an “irreversible and irreparable” process. She also argued that in case the mercy plea of similarly placed convicts is favourably considered by the President of India, the change in circumstance would entitle Kumar to file a fresh mercy plea.

Present in court were Nirbhaya’s parents, who paid close attention to the proceedings. Advocates Seema Kushwaha and Jitender Kumar Jha, who represented them, argued that the convicts were trying to thwart justice by adopting delaying tactics. Jha also stated that according to a provision of the Delhi Prison Rules, 2018, the jurisdiction to decide such applications, filed by convicts, lay with the government and not with the court.

Unimpressed with the contention, the court observed, “I cannot agree with the contention of the counsel for the victim that the jurisdiction to dispose of the application at hand vests with the government and not this court.” Neither did the provision, it went on to add, confer any power upon the executive authority to cause the order of the death sentence to be carried into effect nor did it give any judicial power to the authority to deal with such applications.

The court also pointed out that the execution of sentence shall in all cases be postponed pending receipt of orders of the President. The court, as a result, had no “hesitation in observing” that the execution of warrant with respect to convict Vinay ought to be postponed. The court held, “As a cumulative effect of the discussion, I am of the opinion that the execution of warrants issued by this court by order dated January 17, 2020 deserves to be postponed till further order.”

Legal provisions

Section 364A of the Indian Penal Code

Sec 364A: Too harsh a provision?

TIMES NEWS NETWORK 2013/07/05

New Delhi: The Supreme Court had laid down the “rarest of rare” criteria for courts to award death penalty only in select heinous and gruesome murder cases.

In this background, can Parliament enact a law providing for mandatory death penalty for those found guilty of murdering a person after kidnapping him to demand ransom? Would this not amount to pushing every offence of kidnap for ransom involving murder of the victim into ‘rarest of rare’ category without a judicial determination to that effect?

This question was framed by Justices T S Thakur and S J Mukhopadhaya while referring to a petition challenging the constitutional validity of Section 364A of Indian Penal Code, which imposes mandatory death penalty in kidnap for ransom involving murder of the kidnapped.

The petition was filed by one Vikram Singh, who was convicted under Sections 302 (murder) and 364A of the IPC and awarded death penalty on both counts. The apex court had upheld his conviction and sentence.

But in his petition before the Supreme Court, his counsel D K Garg argued that if the court came to the conclusion that punishment provided under Section 364A of IPC was unconstitutional, then a lenient view could be taken on the death penalty awarded to his client under Section 302.

He argued that Section 364A made even a first time offender liable to be punished with death, which was too harsh to be considered just and appropriate.

Appearing for the Union government, additional solicitor general Sidharth Luthra argued, “It is within the legislative competence of Parliament to provide remedies and prescribe punishment for different offences depending upon the nature and gravity of such offences and the societal expectation for weeding out ills that afflict or jeopardize the lives of citizens and the security and safety of vulnerable sections of the society, especially children who are prone to kidnapping for ransom and being brutally killed if their parents are unable to pay the ransom amount.

“The provisions of Section 364A are not only intended to deal with cases of kidnapping for ransom involving murder of victim but also cases in which terrorists and other extremist organizations resort to kidnapping for ransom or to such other acts only to coerce the government to do or not to do something.”

The court agreed with Luthra that the petitioner had not questioned the competence of Parliament in enacting the law and said the petitioner challenged it only on the ground of harshness.

“The questions (asked by the petitioner) may require an authoritative answer... The peculiar situation in which the case arises and the grounds on which the provisions of Section 364A are assailed persuade us to the view that this case ought to go before a larger bench of three judges for hearing and disposal.”

Judiciary vs Parliament, the debate

Who should debate death penalty: SC or Parliament?

The Times of India, Aug 03 2015

Dhananjay Mahapatra

For the past many decades, we have witnessed a psychological and constitutional battle between two classes -those seeking abolition of death penalty and others who lean for its retention. Yakub Abdul Razak Memon's last-gasp attempts to seek stay of his execution has brought the spotlight back on the debate between abolitionists and retentionists.

Petitions to save Yakub from the gallows assumed a Phoenix-like character as the execution time approached.Dismissal of one was quickly followed by another. Such is the importance given to right to life by the Supreme Court that it opened its doors postmidnight and heard Yakub's plea till the crack of dawn.

The rejection of his final appeal drew the ire of activistlawyers who had virtually taken the legal battle as an all-out war against retentionists.

Their sombre mood soon turned combative. Many renowned advocates who have doggedly fought for human rights for years sniped at the justice delivery system and government, saying a “lynch mob“ and “bloodlust“ attitude had resulted in a “tragic mistake by the SC“.

Till 1973, the law had given absolute discretion to the judges to choose between death penalty and life imprisonment in murder cases. Despite this, the SC had repeat edly cautioned the trial courts to exercise discretion, keeping in mind the criminal and not the crime.

In 1973, the new Criminal Procedure Code made it imperative that life imprisonment was the rule and death penalty the exception for murder convicts. It also said the judge was duty-bound to record special reasons for which heshe preferred to award death penalty instead of life term.

The analysis of `special reason' led the SC to devise the `rarest of rare' doctrine for award of death penalty in the Bachan Singh case in 1982 while upholding the validity of capital punishment. This we will deal with a little later.

Even prior to the enactment of the new CrPC, a five judge SC bench in Jagmohan Singh vs state of UP (1973 AIR 947) had answered alleged arbitrariness in imposing death penalty , which the petitioner said extinguished every constitutional right of a convict, and that there was no guideline for judges in deciding which cases warranted imposition of capital sentence.

It had said, “The exercise of judicial discretion on well-recognized principles is, in the final analysis, the safest possible safeguard for accused.“

Seven years later, a threejudge bench headed by Justice V R Krishna Iyer dealt with a similar question in Rajendra Prasad vs State of UP (1979 AIR 916). It had cautioned against individual cases being made examples to argue either for abolition or retention.

“Personal story of an actor in a shocking murder, if considered, may bring tears and soften the sentence. He might have been a tortured child, an ill-treated orphan, a jobless man or the convict's poverty might be responsible for the crime,“ it had said.

However, it upheld the constitutional validity of death penalty saying there could be a situation where law-breakers brutally kill law enforcers trying to discharge their function. “If they are killed by designers of murder and the law does not ex press its strong condemnation in extreme penalization, justice to those called upon to defend justice may fail. This facet of social justice also may in certain circumstances and at certain stages of societal life demand death sentence.“

Four years later, a constitution bench by four-to-one majority upheld the validity of death penalty in Bachan Singh case on August 16, 1982. It had classified murders into two broad categories -one committed purely for private reasons and the other which “unleash a tidal wave of such intensity , gravity and magnitude, that its impact throws out of gear the even flow of life“.

It explained the stand of abolitionists. “Statistical attempts to assess the true peno logical value of capital punishment remain inconclusive.Firstly , statistics of deterred potential murderers are hard to obtain. Secondly , the approach adopted by the abolitionists is over simplified at the cost of other relevant but imponderable factors, the appreciation of which is essential to assess the true penological value of capital punishment. The number of such factors is infinitude, their character variable, duration transient and abstract formulation difficult,“ it had said.

However, it had sounded caution. “Judges should never be blood-thirsty . Hanging of murderers has never been too good for them. Facts and figures, albeit incomplete, furnished by the Union of In dia, show that in the past, courts have inflicted the extreme penalty with extreme infrequency -a fact which attests to the caution and compassion they have always brought to bear on the exercise of their discretion.“

The statistics and studies in the past few decades have been woefully inadequate to help the SC arrive at a definitive opinion about the efficacy of death penalty. It is time for abolitionists to spend their energies convincing representatives of people to raise the matter in Parliament and bring an amendment to the provisions of law providing for death penalty rather than blame the judiciary for imposing the punishment in `rarest of rare' murder cases.

Find alternatives to hanging: SC to government

Krishnadas Rajagopal, October 6, 2017: The Hindu

Death convicts should die in peace and not in pain, it says. Why can’t hanging as a means of causing death of condemned prisoners stop? Find alternatives to death by hanging, SC tells govt.

The condemned should die in peace and not in pain. A human being is entitled to dignity even in death, the court observed.

The government should look to the “dynamic progress” made in modern science to adopt painless methods of causing death.

A Bench led by Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra issued notice to the government and ordered it to respond to the issue in the next three weeks.

“Legislature can think of some other means by which a convict, who under law has to face death sentence, should die in peace and not in pain. It has been said since centuries that nothing can be equated with painless death,” Chief Justice Misra observed in the order.

The court clarified that it was not questioning the constitutionality of the death penalty, which has been well settled by the apex court, including in the Bachan Singh case reported in 1983.

The court said Section 354 — which mandates death by hanging — of the Code of Criminal Procedure has already been upheld.

However, the provision of hanging to death may be re-considered as “the Constitution of India is an organic and compassionate document which recognises the sanctity of flexibility of law as situations change with the flux of time.”

The fundamental right to life and dignity enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution also means the right to die with dignity, the court said.

The order comes on a writ petition filed by Delhi High Court lawyer Rishi Malhotra, who sought the court’s intervention to reduce the suffering of condemned prisoners at the time of death. Mr. Malhotra said a convict should not be compelled to suffer at the time of termination of his or her life. “When a man is hanged to death, his dignity is destroyed,” he submitted.

During the hearing, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, one of the three judges on the Bench along with Justice A.M. Khanwilkar, pointed out that in the U.S. a prisoner suffers for almost 45 minutes before his death by lethal injection.

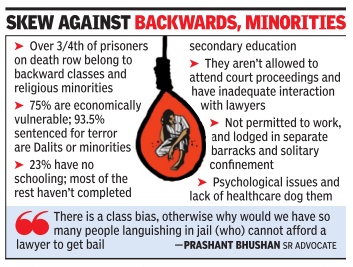

Legislative wants expansion, judiciary wants restriction

The statistics on the state of death penalty in 2018 is an indication of the confusion that besets use of death penalty in India. Drastically different treatment by the legislature, trial courts and the appellate judiciary further intensifies competing tensions in administration of the death penalty.

Calls for death penalty began early on in the year in the backdrop of incidents in Kathua and Unnao. 2018 also saw the prime minister encouraging the death penalty in his Independence Day speech and amendments to IPC and Pocso introducing the death penalty for rape of children.

As far as its judicial treatment is concerned, trial courts in 2018 imposed a record number of 162 death sentences – the highest in nearly two decades. The Supreme Court, on the other extreme, commuted 11 out of the 12 death sentence cases it decided and continued to signal concerns with administration of the death penalty by courts below.

The legislative expansion of death penalty is not new. In the last five years, Parliament passed two other laws introducing death penalty. The Delhi gang rape prompted amendments to IPC in 2013 introducing death penalty for certain sexual offences. In 2016, the Anti-Hijacking Act was passed prescribing death penalty as well.

The legislature guided by political and public reactions has immense faith in death penalty as a response to heinous crimes. But, irrespective of public notions, the law requires courts to consider aspects beyond just the crime when imposing death sentence.

Socioeconomic circumstances of the individual, age, past history, time spent in prison, and the probability of reformation are some factors, which the Supreme Court itself has declared as integral to the sentencing process. However, in reality all levels of the judiciary have for long struggled with using their own terms of reference in administering the death penalty uniformly.

Given this context, expanding the use of death penalty in an already constitutionally suspect framework threatens to weaken the criminal justice system even further. Lack of cohesion within the judiciary is evident from multiple instances when the appellate judiciary has pushed back against the eagerness of trial courts in imposing death penalty.

The Supreme Court has time and again indicated that death sentence is being used by the lower courts more liberally than is intended. The ‘Death Penalty India Report, 2016’ found that over a 15-year period from 2000 to 2015, less than 5% of death sentences were eventually upheld by the Supreme Court.

This trend seems to be continuing. In 2018 itself, various high courts commuted death sentences in 55 cases, of which 24 involved sexual offences. Interestingly, out of the nine death sentences imposed by trial courts under the 2018 law, six were commuted by the respective high courts.

On its part the Supreme Court commuted 11 death sentences in 2018, including a dissenting opinion by Justice Kurian Joseph calling for the abolition of the penalty itself. Six of these commutations by the Supreme Court involved charges pertaining to sexual offences. Be that as it may, the Supreme Court’s performance on death penalty sentencing is also rife with inconsistencies as traced by ‘Lethal Lottery: The Death Penalty in India’, a report analysing over 50 years of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on this issue.

It is evident that death penalty encounters different responses at various levels of the judiciary. While the trial courts demonstrate an exaggerated affection for death penalty, appellate courts seem to be increasingly sceptical.

This incoherence has been particularly glaring in the past year. The legislature’s faith in death penalty, then, is in sharp contrast to this reality and its reliance betrays an honest evaluation of the criminal justice system.

Procedure before the execution

The procedure in brief

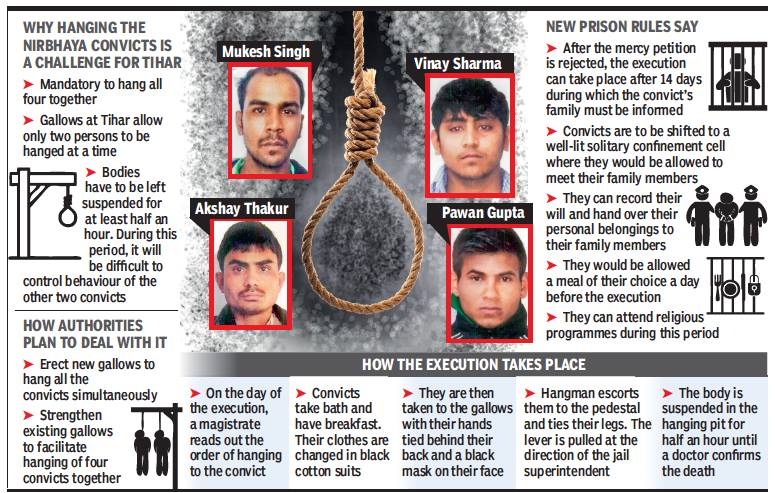

Abhinav Garg, Dec 20, 2019: Times of India

HOW THE PROCESS BEGINS

1. Starts with fast-track

Trial courts (or fast-track courts) handling cases of sexual offences against women and children are bound by deadlines. They need to decide the case within six months after filing of the charge-sheet. But on an average, trial courts take between 1 and 2 years to reach a verdict notwithstanding the day-to-day hearing in cases mandated by Section 309 CrPC.

2. Higher courts But high courts and the Supreme Court deal with such matters on a case-by-case basis. There is no fixed time-frame; it is up to the chief justice or the presiding judge to take a call.

3. Review plea

After conviction by the Supreme Court, a convict gets 30 days’ time to seek review under Article 137 of the Constitution. Even after a review plea is dismissed, the convict can file a curative petition invoking Article 142 (inherent powers) of the Supreme Court. There is no time-frame within which it has to be filed; but courts have largely accepted six months after dismissal of review plea as the standard.

4. Mercy plea

As a last resort, a convict has right to seek mercy by filing a petition directly with the President. The process provided under Article 72, however, doesn’t provide for any prescribed procedure to deal with such mercy petitions.

5. Leniency

Indian courts and jail administration are generally lenient if there is delay in filing of review, curative or mercy petitions by a convict, recognising that imprisoned persons find it difficult to hire lawyers and prepare petitions.

TWO CASES THAT SHOW HOW PLEAS FOR MERCY PROGRESS Nithari killings: How Koli escaped the plea at the 11th hour in 2014

Surendra Koli's hanging was fixed for September 2014 but the SC stayed the execution in the middle of the night over a pending review petition

16 FIRs were registered against Surendra Koli for rape and murder in the Noida serial murders case involving him and his employer Moninder Singh Pandher that came to light in 2006. Death sentence was handed to Koli in 11 cases by the trial court, while 5 cases are still pending.

- In 2009, the first death sentence to Koli was awarded by the trial court. Allahabad HC confirmed the death sentence.

- In 2011, SC dismissed the appeal and upheld the death sentence. Koli then filed a mercy petition.

- In 2014, President rejected the mercy petition. The hanging was fixed for September after the trial court issued a black warrant (the final order). However, SC stayed the execution at 2am over Koli’s pending review petition after lawyers appeared for him and got him a reprieve on this ground. SC rejected the review in October.

In 2015, Koli and an NGO separately moved the Allahabad HC against hanging on the grounds of delay in deciding the mercy petition. The high court commuted death to life citing 2014 SC ruling in Shatrughan Chauhan case. Since then, Koli has been convicted and awarded death sentence in 10 other cases, including one in April 2019. Due to multiple cases and trials and witnesses/victims, justice has been delayed with each case likely to go through the full cycle of appeals and review. Jurisprudence in capital punishment argues that since death is irrevocable, authorities should wait for a convict to exhaust all legal options before carrying out the sentence.

Rajiv Gandhi assassination: Decades of back and forth over mercy petitions

Nalini Sriharan, arrested for being part of the plot to kill Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991, is India's longest-serving woman prisoner Nalini Sriharan was arrested for being part of the plot to kill former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi in May 1991. She is the longest-serving woman prisoner in India.

Though all 26 accused were given the death penalty by a Special TADA court in 1998, SC in 1999 confirmed capital punishment only in the case of Murugan, Santhan (both Sri Lankan Tamils), AG Perarivalan and Nalini, wife of Murugan.

- In 2000, Nalini, however, escaped the noose following a Tamil Nadu Cabinet decision and the governor’s assent to commute her death penalty to life. The clemency petitions of the other three were rejected by the President in 2011.

- In 2011, execution of three convicts was fixed for September 9 that year but Madras high court stepped in and stayed the move. The matter was transferred to the SC.

- In 2014, SC commuted the death sentence on grounds of delay in disposing of mercy pleas. It also said the state government may consider freeing the convicts under powers vested with it. TN cabinet wanted to immediately release Santhan, Murugan, Perarivalan, Nalini, Robert Pious, Jayakumar and Ravichandran and sent its decision to Centre under Section 435 CrPC. But Centre secured a stay from the top court.

- In 2017, SC dismissed the Centre’s curative plea seeking to re-impose death penalty on Nalini and other convicts.

- In 2019, Madras high court granted Nalini 30 days’ parole. Nalini has also sought remission of her sentence from the Tamil Nadu governor.

Dos and Don'ts of execution by hanging

There has to be a minimum gap of 14 days between the date of execution and the date when a convict's mercy petition is rejected — counted from the date of receipt of such communication — as per the Model Prison Manual 2016.

When more than one person is scheduled to be executed by hanging, an appeal to a higher court or a special leave to appeal to the Supreme Court by even one of the convicts is enough to postpone the hanging of all the convicts. All executions by hanging are to be carried out early in the morning before it gets too bright, with the convict's hands tied behind his back. However, no convict can be executed on a public holiday.

Heavier the prisoner, the easier it is to execute him — as heavier convicts require a lesser drop distance needed to break the neck and sever the spine. The rope, made of cotton yarn or manila, should be of 2.59-3.81 cm in diameter and should have wax or butter applied to it. Two spare ropes per convict are kept in reserve, ready on the scaffold, in case of a mishap while carrying out the execution.

No prisoners are allowed where the hanging is to be carried out and are to be kept under lock and key till the execution takes place. Even the convict to be hanged is not allowed to see the gallows — his face is to be covered by a cotton cap with a flap, with the body left hanging for at least 30 minutes.

Convicts get 14 days if mercy plea is rejected

Somreet Bhattacharya, Dec 13, 2019 Times of India

The hanging of the four Nirbhaya gang-rape and murder case convicts may be imminent but it’s unlikely to take place in the next few days. Supreme Court is scheduled to hear a review petition filed by one of the convicts, Akshay Singh, on December 17, although the 30-day window for filing mercy pleas is now over, Tihar Jail authorities said.

The jail authorities also have to give a 14-day period to the convicts to “mentally prepare” for the execution, write a will, etc.

Earlier this week, a review petition filed by one of the convicts, Pawan Gupta, was rejected by the apex court. Another convict, Vinay Sharma, who had appealed for a mercy from the President, later withdrew claiming that he did not sign it. He also sought for a permission to file a fresh plea.

Convicts to get 14 days if mercy plea is rejected

Speaking to TOI, former Tihar jailer Sunil Gupta explained that unlike in the past, jail authorities now have to follow jail rules drafted after the hanging of Parliament attack convict Afzal Guru. Under this, the convicts will be granted a provision to seek a curative petition even after the mercy plea to the President is rejected. The petition is ,however, subjected to its admission by the court.

Gupta, who served as a jailor and legal officer with the Tihar Jail since 1981 and has witnessed 14 hangings, including that of Afzal Guru, said the new prison rules, prepared on the basis of a petition by Shatrugan Chauhan, allow the death row convicts to meet their family members, who will have to be clearly informed about the rejection of the mercy pleas, in writing well in advance before the hanging. This was corroborated by other sources too.

Under the jail rules, implemented in 2018, the convicts as well as their families will be handed the death sentence in a red envelope during the 14-day period. The acknowledgement and date of its receipt have to be entered in a register with the superintendent.