Jammu & Kashmir, history: 1947-48

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Accession to India: an overview

A

Mediawire, Nov 2, 2021: The Times of India

From: Mediawire, Nov 2, 2021: The Times of India

The state of Jammu and Kashmir as it exists today was created by the British in 1846. To further ‘weaken the Sikh’s after their defeat at Sobraon, the British government separated Kashmir from the Sikh empire and ‘sold’ it to Raja Gulab Singh, ruler of Jammu. The treaty of Amritsar -notoriously referred to in Kashmir as the sale deed of Kashmir- the British government made over to Raja Gulab Singh and the heirs male of his body forever and in independent possession, the state of Jammu and Kashmir for a consideration of 75 lakhs of British Indian rupees.

Gulab Singh’s Dogra dynasty ruled Kashmir till 1947, till the attack by Pathan tribesmen, which was masterminded by the Pakistan army and led by its senior officer Akbar Khan. The British had succeeded in forging an uneasy peace with the tribes of the North-West Frontier but after the British withdrew, Pakistan incited the tribesmen into launching their attack. By Oct. 1947, about 5,000 tribesmen had entered Kashmir.

The tribesmen transited through Pakistan carrying modern military gear. The first standoff was at Muzaffarabad where they faced a battalion of Dogra troops, capturing the bridge between Muzaffarabad and Domel, which itself fell to the attackers the same day. Over the next two days, they took Garhi and Chinari. The main group of attackers then proceeded further towards Uri.

Battle of Uri

At Uri, Brigadier Rajinder Singh, who led J&K state forces, was killed. “He and his colleagues will live in history like the gallant Leonidas. The battle at Uri holds significance in accession history as it likely helped Maharaja Hari Singh avoided capture and bought the Indian government valuable time to bring in more forces. After the battle, the tribesmen invaders travelled down the Jhelum River to Baramulla, the entry point into the Kashmir Valley.

On October 24, the Maharaja made an urgent appeal to the Indian government. He waited for a response, while the Cabinet’s defence committee met in Delhi. V. P. Menon, administrative head and secretary of the state’s department, was instructed to fly to Srinagar on October 25. Menon’s priority was to get the Maharaja and his family out of Srinagar. There were no forces left to guard the capital and the invaders were at the door. The ruler left the Valley by road for Jammu. On October 26, after a Cabinet defence committee meeting, the government decided to fly two companies of troops to Srinagar. Menon himself took a plane to Jammu where the ruler was stationed.

Governor-general Mountbatten had contended it would be the 'height of folly' to send troops to a neutral state without an accession is completed, "but that it should only be temporary before a referendum." Neither Nehru nor Sardar Patel attached any importance to the “temporary” clause, but Menon was carrying a message for the ruler: he had to join the Union if he wanted to ward off the invasion. The ruler agreed to accede.

In fact, according to Menon’s memoirs, he had left word with an aide that if Menon did not return with an offer, he was to shoot the ruler in his sleep. Hari Singh signed the Accession letter regretting that the invasion had left him with no time to decide what was in the best interest of his state, to stay independent or merge with India or Pakistan. Mountbatten while accepting the request for Accession, mentioned that referendum would be held in the state when the law-and-order situation is restored.

Sheikh Abdullah took charge of an emergency administration in Kashmir. Nehru appointed the former Kashmir Prime Minister N Gopalswamy Ayyangar as a cabinet minister to look after Kashmir affairs. Ayyangar was one of the chief architects of Article 370. The article allowed the state a certain amount of autonomy - its own constitution, a separate flag and freedom to make laws. Foreign affairs defence and communications remained the preserve of the central government.

As a result, Jammu and Kashmir could make its own rules relating to permanent residency, ownership of property and fundamental rights. It could also bar Indians from outside the state from purchasing property or settling there. The constitutional provision has underpinned India's often fraught relationship with Kashmir, the only Muslim-majority region to join India at partition.

The Instrument of Accession is a legal document executed by Maharaja on October 27, 1947. By executing this document under the provisions of the Indian Independence Act 1947, he agreed to accede to the Dominion of India.

The Bharatiya Janata Party had from the inception long opposed Article 370 and revoking it was its political agenda and in the party's 2019 election manifesto, it was more specifically promised to the voters. They argued it needed to be scrapped to integrate Kashmir and put it on the same footing as the rest of India. After returning to power with a massive mandate in the April-May general elections, the government lost no time in acting on its pledge, and on August 5th,2019 by a Constitutional amendment the Article 370 was made inoperable and Article 35-A was scrapped and the State of Jammu & Kashmir was bifurcated into two Union Territories.

B

Mediawire, Nov 2, 2021: The Times of India

Mountbatten accepts Accession

In a letter sent to Maharaja Hari Singh on October 27, 1947, Lord Mountbatten accepted the accession with a remark, "it is my government’s wish that as soon as law and order have been restored in Jammu and Kashmir and her soil cleared of the invader the question of the State's accession should be settled by a reference to the people. Lord Mountbatten's remark and the offer made by the Government of India to conduct a plebiscite or referendum to determine the future status of Kashmir led to a dispute between India and Pakistan regarding the legality of the accession of Jammu and Kashmir. India claims that the accession is unconditional and final while Pakistan maintains that the accession is fraudulent.

The accession to India is celebrated on Accession Day, which is held annually on October 26.

The legal ruler Maharaja Hari Singh has explicitly mentioned that he is acceding to Indian Union.

“And whereas the Government of India Act, 1935, as so adapted by the governor-general, provides that an Indian State may accede to the Dominion of India by an Instrument of Accession executed by the Ruler thereof. Now, therefore, I Shriman Inder Mahander Rajrajeswar Maharajadhiraj Shri Hari Singhji, Ruler of Jammu and Kashmir State, in the exercise of my sovereignty in and over my said State do hereby execute this my Instrument of Accession and I hereby declare that I accede to the Dominion of India with the intent that the governor-general of India, the Dominion Legislature, the Federal Court and any other Dominion authority established for the Dominion shall, by this my Instrument of Accession but subject always to the terms thereof, and for the purposes only of the Dominion, exercise about the State of Jammu and Kashmir (hereinafter referred to as "this State") such functions as may be vested in them by or under the Government of India Act, 1935, as in force in the Dominion of India, on the 15th day of August 1947, (which Act as so in force is hereafter referred to as "the Act,” read the document signed by him.

The document further stated: “I hereby assume the obligation of ensuring that due effect is given to the provisions of the Act within this state so far as they are applicable therein by this my Instrument of Accession. I accept the matters specified in the schedule hereto as the matters concerning which the Dominion Legislatures may make laws for this state.

I hereby declare that I accede to the Dominion of India on the assurance that if an agreement is made between the Governor-General and the ruler of this state whereby any functions about the administration in this state of any law of the Dominion Legislature shall be exercised by the ruler of this state, then any such agreement shall be deemed to form part of this Instrument and shall be construed and have effect accordingly.”

Nothing in this Instrument shall empower the Dominion Legislature to make any law for this state authorizing the compulsory acquisition of land for any purpose, he agreed to provide facilities to the Indian government to exercise suzerainty over Jammu and Kashmir.

Accession empowers Indian Union

“I hereby undertake that should the Dominion for a Dominion law which applies in this state deem it necessary to acquire any land, I will at their request acquire the land at their expense or if the land belongs to me transfer it to them on such terms as may be agreed, or, in default of agreement, determined by an arbitrator to be appointed by the Chief Justice Of India. Nothing in this Instrument shall be deemed to commit me in any way to acceptance of any future constitution of India or to fetter my discretion to enter into arrangements with the Government of India under any such future constitution.

Nothing in this Instrument affects the continuance of my sovereignty in and over this state, or save as provided by or under this Instrument, the exercise of any powers, authority and rights now enjoyed by me as Ruler of this state or the validity of any law at present in force in this state. I hereby declare that I execute this Instrument on behalf of this state and that any reference in this Instrument to me or the ruler of the state is to be construed as including to my heirs and successors,” read the document signed by Maharaja Hari Singh on Octo. 26, 1947

Some scholars have questioned the official date of the signing of the accession document by the Maharaja. They maintain that it was signed on October 27 rather than October 26. However, the fact that the Governor-General accepted the accession on October 27, the day the Indian troops were airlifted to Kashmir, is generally accepted. An Indian commentator, Prem Shankar Jha, has argued that the accession was signed by the Maharaja on October 25 1947, just before he left Srinagar for Jammu. Before taking any action on the Maharaja's request for help the Govt. of India decided to send Mr V.P. Menon, representing the Government of India who flew to Srinagar on the (25.10.1947). On realizing the emergency, V.P Menon advised the Maharaja to leave immediately to Jammu to be safe from invaders.

Pluralists, democratic heads needed to support the crown

The Maharaja did the same and left Srinagar for Jammu that very night (25.10.1947) while Menon and Mr Meher Chand Mahajan Prime Minister flew to Delhi early next morning. (26.10.1947). On reaching New Delhi, the Indian government assured Menon and Mahajan that they will militarily rescue Jammu and Kashmir State only after the signing of the accession instrument. Hence Menon flew back to Jammu immediately with the Instrument of Accession. On reaching Jammu he contacted the Maharaja who was in sleep at that time after a long journey. He woke up and at once signed the Instrument of Accession.

V.P Menon flew back immediately on October 26 to Delhi along with the legal documents, completing the proper and legal Accession of the state of Jammu and Kashmir with the Indian Union.

Since then, Jammu and Kashmir are a shining crown on the head of Bharat Mata or Indian Union. It is an utmost duty for every citizen to protect this crown, its pride and glory. The glory of Jammu and Kashmir is associated with the splendour of India. Neither there should be any attempts to truncate this crown, nor there should be a venture to narrow the head of Bharat Mata. A pluralistic, democratic liberal, accommodating head of the Indian Union is best in the interests to support this crown.

(Written by Shri Ashok Bhan, who is a senior advocate at Supreme Court of India and distinguished fellow USI, Chairman-Kashmir (Policy & Strategy) Group. He can be reached at: ashokbhan@rediffmail.com. The views expressed in the above advertorial are personal, BCCL and its group publications disassociate from the views expressed above)

Disclaimer: Content Produced by Samrudh Bharat Social Welfare Foundation

Accession: Nehru, Patel, Hyderabad, Junagadh, the UN, the ceasefire and J&K

Yashee, Dec 16, 2023: The Indian Express

Nehru, Patel, and accession

After the British left, two important princely states refused to join either India or Pakistan. Jammu and Kashmir had a Hindu ruler in a Muslim-majority state. Hyderabad had a very high-profile and very rich Muslim ruler in a Hindu-majority state. Both wanted independence.

Nehru was firm that Kashmir should be a part of India. Patel, while very clear that a hostile Hyderabad would be a “cancer in the belly of India”, believed that “if the Ruler [of Kashmir] felt that his and his State’s interest lay in accession to Pakistan, he would not stand in his way” (from My Reminiscences of Sardar Patel, by V Shankar, his political secretary). Patel’s opinion about Kashmir changed on September 13, 1947, when Pakistan accepted the accession of Junagadh.

Before we move on to the first India-Pakistan war, its ceasefire, and India going to the UN (Nehru’ supposed “blunders”), let’s look at the accession of Junagadh and Hyderabad.

Accession of Junagadh

Junagadh, in the Kathiawar region of Gujarat, was ruled by Nawab Muhammad Mahabat Khanji III. Initially, the Nawab had given indications of joining India. However, months before Independence, he got a new prime minister, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto (father of Pakistan’s future PM, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto).

Upon Bhutto’s persuasion, the Nawab on August 14, 1947, announced he would join Pakistan, though most of his subjects were Hindu and Junagadh had no direct land link to the new country. Pakistan accepted the accession.

Incensed, India sent a small military to support two of Junagadh’s tributary states that did not agree with the Nawab’s decision. Junagadh’s residents too rose in protest. By November, the Nawab had fled to Karachi and Bhutto had to ask India to take over the province. A plebiscite was held, where 91% of the voters chose to stay in India.

Accession of Hyderabad

Adhir Ranjan in Parliament mentioned Victoria Schofield’s book. Here’s what it says about the proposed “barter”, “Corfield had suggested that if Hyderabad, second largest of the princely states, with its Hindu majority and Muslim ruler, and Kashmir, with its Hindu ruler and Muslim majority, were left to bargain after independence, India and Pakistan might well come to an agreement. ‘The two cases balanced each other . . . but Mountbatten did not listen to me… Anything that I said carried no weight against the long-standing determination of Nehru to keep it [Kashmir] in India.’”

Hyderabad joining Pakistan was never a practical proposition. However, Patel gave Nizam Mir Usman Ali a long rope, partially because of the prestige he enjoyed in the Muslim world — his sons were married to the daughter and niece of the deposed Caliph of Ottoman, Abdulmejid II, who even wanted his daughter’s heir to succeed him as the Caliph. Till three months after Independence, all India had with Hyderabad was a stand-still agreement, which meant ties remained as they were under the British. Negotiations continued.

However, soon, the situation on the ground demanded faster action. Revolt against the Nizam’s rule was widening, for democracy as well as against large landholdings, forced labour, and excessive tax collection. An outfit meant to cement the Nizam’s position, the Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen, was getting more violent, with its paramilitary wing called the ‘razakars’ brutally attacking all opponents.

Finally, on September 13, 1948, the Indian Army was sent to Hyderabad under Operation Polo. In three days, the Nizam’s forces surrendered.

Accession of Jammu and Kashmir

Maharaja Hari Singh refused to accede to either dominion, preferring independence. In September, lorries carrying petrol, sugar, salt, clothes, etc. for J&K were stopped on the Pakistan side of the border, possibly to create pressure for accession. Meanwhile, a revolt broke out in Poonch against Hari Singh, not a very popular ruler.

On September 27, 1947 [India after Gandhi, by Ramachandra Guha], Nehru wrote to Patel that the situation in J&K was “dangerous and deteriorating”. Nehru believed Pakistan planned to “infiltrate into Kashmir now and to take some big action as soon as Kashmir is more or less isolated because of the coming winter” [Schofield]. The infiltrators came in October.

India maintains they were armed and sent by Pakistan. Pakistan claims these were tribesmen acting on their own, “to avenge atrocities on fellow Muslims”. Hari Singh asked India for military help, and to secure this help, acceded.

Indian troops quickly secured Srinagar, and then began driving out the infiltrators from other parts.

Nehru’s “blunders”

This is where we come to the “blunders” of Nehru mentioned by Shah. Why did India go to the UN, instead of defeating Pakistan in battle?

First, it was under pressure from Louis Mountbatten, then Governor-General of India, and the British government. British PM Clement Attlee had written to Nehru: “I am gravely disturbed by your assumption that India would be within her rights in international law.”

Second, there was the risk of the war spilling outside Kashmir and into Punjab, which had just suffered the brutalities of Partition. Third, the war was costing India dearly: Patel himself, addressing locals at a library opening in Delhi in December 1947, had said, “You must realise that nearly Rs 4 lakh are being spent every day on the Kashmir operations alone.” Fourth, the Indian government seems to have believed that a ‘neutral’ forum like the United Nations would agree with its position, and the Kashmir issue would be resolved once and for all.

Instead, India was shocked by British and American hostility. The US had seen in Pakistan a valuable asset against the Soviet Union. Britain, after having just partitioned Palestine, did not want to oppose another Muslim country. Soon, Nehru himself regretted ever going to the UN. He told Mountbatten that “power politics and not ethics” were driving the UN, “which was being completely run by the Americans” [Guha]. He went on to resist all demands of a plebiscite — from the UN to the Commonwealth — till all Pakistani intruders were out of Kashmir.

As for the ceasefire, it was supervised by the UN. While many in India continue to see it as an opportunity lost, Pakistan had then seen it as favouring India. “The ceasefire was imposed on us at a time when it suited the enemy most,” wrote Colonel Abdul Haq Mirza, who fought as a volunteer from October 1947, as quoted by Schofield. “Four months of operational period was allowed to the Indians to browbeat the ill-equipped Mujaheddin and to bring back vast tracts of liberated territories in their fold.”

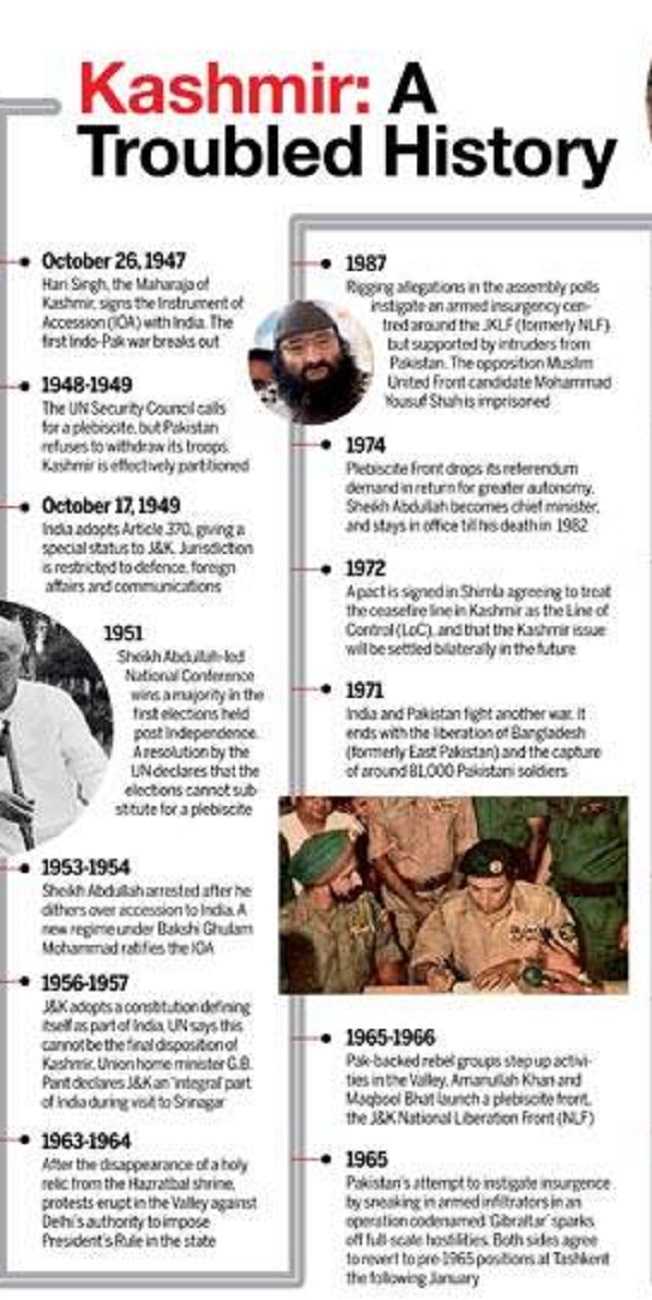

1947-90: A timeline

August 14, 2008

From the archives of “The Times of India”: 2008

As Jammu & Kashmir slips into another spell of anarchy, here’s a look at the history and social indicators of the scenic state that was once known for its unique syncretic culture where diverse faiths prospered in peace.

Ancient Era : According to mythology recorded in Rajatarangini, the history of Kashmir written by Kalhana in the 12th century, the Kashmir Valley was formed when sage Kashyapa drained a lake. It became a centre of Sanskrit scholarship and later a Buddhist seat of learning

14th century : Islam becomes the dominant religion in Kashmir. The Sufi-Islamic way of life of Muslims here complements the ‘rishi’ tradition of Kashmiri Pandits, leading to a culture where Hindus and Muslims revere the same local saints

1588 : Akbar invades Kashmir and the region comes under Mughal rule

Early 19th century : Sikhs take control of Kashmir. Maharaja Ranjit Singh had earlier annexed Jammu. Scion of the Dogra clan, Gulab Singh, made raja of Jammu in 1820. Singh soon captures Ladakh and Baltistan

1846 : After partial defeat of the Sikhs in the First Anglo-Sikh War, Kashmir is given to Gulab Singh for Rs 75 lakh. Thus the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu (as it’s then called) is formed

Post-1857 : After the first war of independence, kingdom comes under the reign of British Crown. Gulab’s son, Ranbir Singh, becomes ruler

1925 : Hari Singh, Ranbir’s grandson, ascends the throne. His rule is generally considered unpopular

Oct 1932 : Kashmir’s first political party, the Muslim Conference, is formed with Sheikh Abdullah as president. It is renamed National Conference in 1938

August 1947 : At the time of partition, India and Pakistan agree that rulers of princely states will be given the right to opt for either nation. To put off a decision, Maharaja Hari Singh signs a ‘standstill’ agreement with Pakistan to ensure that trade, travel and communication continue

October 1947 : Pashtun raiders from Pakistan’s NWFP invade Kashmir. Hari Singh appeals to Governor General Mountbatten for help. India assures help on condition Hari Singh signs Instrument of Accession. He does, and Indian troops repulse assault from across border. UN invited to mediate and insists opinion of Kashmiris be ascertained. India initially says no to referendum until all raiders are driven out but Nehru two months later agrees to a poll. Pakistan contests accession, claims Indian army illegally entered Kashmir

Jan 1, 1948 : India declares unilateral ceasefire. Under Article 35 of the UN Charter, India files complaint with UN Security Council

Jan 20, 1948 : Security Council establishes a commission and adopts a resolution on Kashmir accepted by both countries. Pakistan is blamed for invading Kashmir and asked to withdraw its forces. A year later, UN passes resolution calling for plebiscite

March 17, 1948 : Sheikh Abdullah takes oath as prime minister of J&K

Jan 1, 1949 : India and Pakistan conclude a formal ceasefire

1949 : Article 370 granting special status to J&K is inserted in Constitution

Aug 9, 1953 : Sheikh Abdullah arrested and imprisoned. His dissident cabinet minister, Bakshi Ghulam Mohammed, appointed PM. Abdullah jailed for 11 years, accused of conspiracy against the state in the ‘Kashmir Conspiracy Case’

1965 : Pakistan attacks India in operation codenamed Gibraltar. Following Pakistan’s defeat, Tashkent Agreement signed

March 30, 1965 : Article 249 of Indian Constitution extended to J&K. Designations like prime minister and president of the state replaced by chief minister and governor.

1972 : India and Pakistan sign Simla Agreement, promising to respect Line of Control until Kashmir issue resolved

Feb 1975 : PM Indira Gandhi and Sheikh Abdullah sign accord. J&K made a ‘constituent unit’ of India. Abdullah becomes CM

1977 : National Conference wins the first post-Emergency elections

1982 : Abdullah dies after naming son, Farooq, successor. Allegations of rigging surface during state elections in the 1980s

1987 :Street protests and demonstrations in Srinagar against inefficiency and corruption against the state government turn into anti-India protests

1989 : Armed militancy erupts. Kashmiri Pandits flee valley. State brought under central rule next year as Army fights Pak-trained militants

1990-present : Armed militancy and terrorism, with international jihadi elements entering the arena, stalk the valley. Elections in 1996 and 2002, especially the latter, bring back some legitimacy to the democratic process but violence continues

From Britain’s Pakistan bias in 1947 to Zia’s 1980s Wahhabisation

Rashme Sehgal, Dec 5, 2019 Rediff

Kashmir's Untold Story Declassified has not come a day too soon given that no state -- now a Union Territory -- has witnessed so much turmoil and received so much attention in the last 70 years.

Written jointly by Iqbal Chand Malhotra and Maroof Raza , the book looks at why the Kashmir valley has been in a state of turmoil for 72 years and why China and its client State Pakistan will continue to back militancy in the years to come.

Malhotra, chairman of AIM Television, produced several documentaries on Kashmir before he and Raza, a strategic affairs expert who anchors a programme on this subject for the Times Now television channel, got down to the task of putting this book together.

"By sustaining the militancy and hybrid war currently on in Jammu and Kashmir, China is seeking to permanently thwart India's attempts to use modern hydrology, to prevent us from tapping into the 19.48% of the waters of the Indus that we are entitled to," Malhotra tells Rediff.com Contributor Rashme Sehgal.

Your book highlights how a conspiracy was hatched around the erstwhile maharaja of J&K Hari Singh to ensure that he acceded to Pakistan and not India. Why did this plan prove to be a failure? The British deep state of which Lord Hastings Ismay (Viceroy Lord Louis Mountbatten's chief of staff) and NWFP (North West Frontier Province) Governor Sir George Cunningham were a part wanted the whole principality of Jammu and Kashmir to accede to Pakistan.

As long as the principality's prime minister Ram Chandra Kak was in the saddle, they were confident that Kak would steer the state towards accession with Pakistan.

Once Kak was dismissed by Maharaja Hari Singh and accession to Pakistan appeared unlikely, the British instituted Operations Gulmarg and Datta Khel respectively to foil possible accession to India.

Operation Gulmarg failed because the invaders were denied British leadership.

This happened because Major Onkar Singh Kalkat, a Sikh officer, gained access to the British devised invasion plans.

Major Kalkat was waiting to hand over charge of the brigade when a demi-official letter arrived from General Sir Frank Messervy stationed at the general headquarters in Rawalpindi.

Attached to the letter was an appendix titled 'Operation Gulmarg - The Plan for the Invasion and Capture of Kashmir' with the operations expected to commence on October 20 1947.

Major Kalkat managed to escape from the frontier settlement of Mir Ali Mirali by the skin of his teeth, arriving in Delhi on October 18 1947.

He informed then defence minister Sardar Baldev Singh of this plan on October 19, 1947.

Sardar Baldev Singh asked the British staffed intelligence directorate to verify Major Kalkat's account, but they paid no heed to it.

It was only after the invasion had started in full swing that Major Kalkat's warning was taken seriously. He was taken to meet Pandit Nehru only on October 24, 1947.

It is my guess that it was this snafu regarding Major Kalkat that made the British mercenaries, who were originally expected to lead the Kabailis or Pathan invaders, to stand down and not lead the invasion.

The rest is history.

The plan for Operation Gulmarg actually started in 1943.

Yes, planning for Operation Gulmarg started way back in 1943.

The British were certain Kashmir would go to Pakistan and pulled out all the stops in advance to ensure this.

Cunningham , in his second term as governor of NWFP, had initiated the forming of the Tucker committee in 1944 that recommended that regular Indian army troops be withdrawn from the Razmak, Wana and Khyber Pass garrisons and be replaced with scouts and khassadars. The northern boundaries of British India were to be defended by Muslim staffed Frontier Scouts and Frontier Constabulary.

In 1943, the British withdrew the army from the north western borders and the withdrawal was completed by 1946.

They were replaced by khassadars with basic detachments of 2,000 of these paramilitary troops being officiated by British officers called district officers.

There were around 25,000 khassadars with 20 to 40 British officers overseeing them.

They would have achieved success had it not been for the show of courage shown by Major Kalkat.

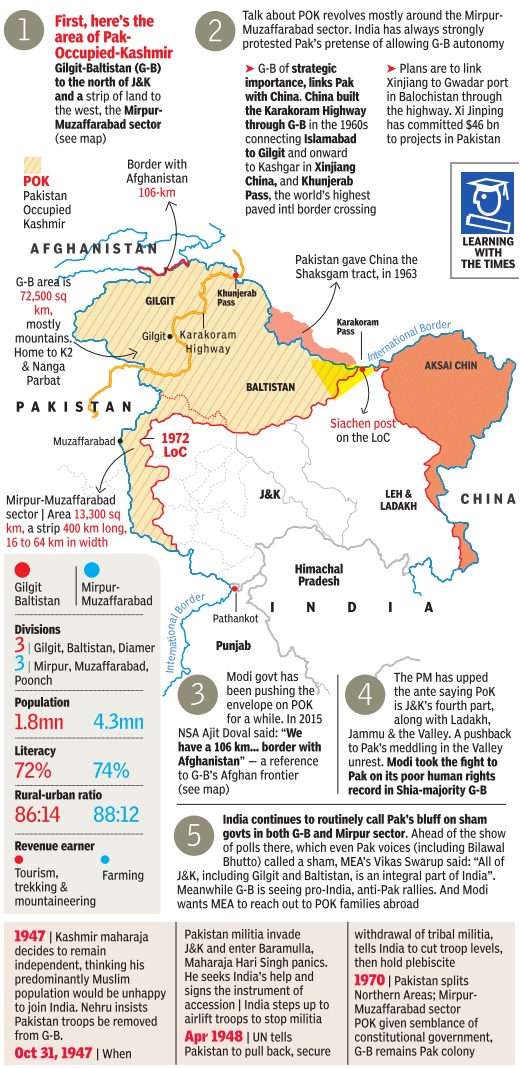

Your book also highlights how the British deep state was active in ensuring Gilgit was taken over by Pakistan. Its strategic importance was something Indian rulers seemed oblivious of.

Unfortunately, the Indian political leadership of that time led by Pandit Nehru were singularly obsessed with the mistaken notion that Sheikh Abdullah called all the shots.

However, Abdullah only represented the valley and no more.

Abdullah was unacceptable in the other four regions of the state, namely Gilgit, Ladakh, Jammu and Muzaffarabad.

Gilgit shared an international border with Afghanistan, Xinjiang and Tibet.

How was Gilgit actually given over to Pakistan?

The conglomeration of the vassal States of Gilgit, Puniyal, Koh-e-Khizr, Yasin, Yashkoman and Chitral were called Gilgit Agency.

In 1943, Colonel Roger Bacon took over as political agent in Gilgit.

Lord Mountbatten announced after becoming viceroy of India that the Gilgit lease would be rescinded on July 31 1947 so that it be returned to Maharaja Hari Singh.

But Lord Ismay, Colonel Bacon and Major Brown in Gilgit had other plans.

Major Brown asked the then governor Ghansara Singh, an appointee of Maharaja Hari Singh, to step down which he refused.

This made way for Operation Datta Khel on the night of November 4 , 1947 where Major Brown and his troops took siege of the governor's residence.

A fierce gun battle followed and the governor and his staff were forced to surrender.

On November 17 , 1947, a Pakistani flag was flying over the governor's flag staff.

It is obvious this operation was the brain child of the British deep state.

This seems to be a common chord -- call it indifference or unawareness about the strategic importance of the regions around J&K For example, when China acquired a large chunk of Aksai Chin, alarm bells should have rung in the Indian establishment, but this did not happen.

The Government of India knew about the Chinese intrusions and purported annexation in Aksai Chin from 1952 onwards.

Why then did the Indian government sign the Pancheel Agreement with China in 1954?

Why did India surrender its consulates in Kashgar, Sinkiang and Gartok in Tibet?

The Chinese followed the annexation of Sinkiang and Tibet by annexing a large chunk of Aksai Chin.

The central leadership chose to ignore it and in fact bent over backwards to cede further sovereign territory in Tibet to China.

This was the principality of Minsar.

China had in 1959, wanted a part of the Gilgit Agency and especially the Shaksgam Valley with its 250 glaciers making it the most glaciated region in the world to be part of China. Were the Chinese conscious even then of the importance of water that saw them push their expansionist design?

That is obvious, otherwise they wouldn't have entered into a territory swap with Pakistan in 1963; they wouldn't have chosen Lop Nor lake in Xinjiang for their nuclear testing site and they wouldn't have annexed the Aksai lake in Aksai Chin having a catchment area of 8,000 sq km as compensation for their planned degradation of Lake Lop Nor with nuclear waste.

Subsequent to this was that China attacked India on October 20, 1962 because they needed greater strategic depth to build the Aksai Chin highway.

The attack on October 20, 1962 by China was to politically consolidate their pre-existing annexation of Indian territory from 1952 onwards.

They were primarily interested in avenging the Treaty of Chushul signed in 1842 between the Sikh empire, Tibet and the Daoguang emperor of China, wherein China had conceded vast tracts in Tibet and Ladakh to the Sikhs.

The Chinese were interested in overthrowing the Treaty of Chushul which had caused them great humiliation and also emboldened the British officered Indian Army to storm the gates of the imperial capital Nanjing and submit the Daoguang emperor to yet another humiliation in the form of The Treaty of Nanjing signed also in 1842.

Making India bleed with a thousand cuts was not a strategy put in place by either Zulfikar Ali Bhutto or Zia-ul Haq , but had its origins in the tenure of Pakistan's longest serving ISI chief Major General Robert Cawthome.

Major General Cawthome was ISI chief from 1949 to 1959 and devised and institutionalised the strategy of 'continuous proxy war' against India. It was he who established the fact that India was an existential threat to Pakistan.

It was he who reciprocated the overtures of China's chief spymaster in the 1950s, Kang Sheng.

How successful was Zia-ul Haq's operation? To turn Kashmiris away from sufism to hard line Wahhabi Islam as also to cleanse non-Muslims from the Kashmir valley?

Why were the valley's leaders and the central establishment napping through all these tumultuous developments?

Zia-ul Haq's strategy of converting Kashmiris to Wahhabi Islam has been almost 90% successful. His successors were almost 100% successful in ethnically cleansing the valley of all Kashmiri Pandits.

In your book you state that militancy in Kashmir is set to intensify.

China is never going to give up on the waters of the Indus river.

By sustaining the militancy and hybrid war currently on in Jammu and Kashmir, China is seeking to permanently thwart India's attempts to use modern hydrology, to prevent us from tapping into the 19.48% of the waters of the Indus that we are entitled to.

1947, Jan- Aug

The British help Pakistan get Gilgit

SANDEEP BAMZAI, May 17, 2017: The Times of India

An empire which is toppled by its enemies can rise again, but one that is toppled from within crumbles that much faster. It could be a Trojan or a saboteur who brings it to its knees. History is replete with such examples — from Achilles in Troy (in Greek mythology, he was a hero of the Trojan War and the central character and greatest warrior of Homer’s Iliad) to Mir Jaffar in the decisive Battle of Plassey (who assembled his troops to assist Nawab Siraj-ud-daulah against a much smaller force led by Robert Clive, but did not lead them into combat, thus neutralising the Nawab of Bengal’s fighting efficacy, leading to his rout and subsequent death). The reprobate British did their best to prevent decolonisation as many of them played their part to the hilt in order to serve the Churchillian diktat of keeping a bit of India, using cunning and subterfuge to blindside Indians, as they were ordered to leave the subcontinent after the Second World War. However, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Patel and even Lord Louis Mountbatten fixed the subversive political department under the wily Sir Conrad Corfield.

There were many deceitful characters floating around in those uncertain times. F. Paul Mainprice was one such gadfly. He came from London’s Bexhill and joined the Indian Civil Service in the late 1930s, serving in Assam and Madras provinces. Towards the end of his service, he was transferred to the political department and served as political agent for the states in Assam and later in the crucial areas of Gilgit and Chilas. In 1947, he was acting political agent in Gilgit, from where he was relieved in August when Gilgit was handed back to the Kashmir government.

He reportedly reached Srinagar around August 26-27 and stayed at the famed Nedous Hotel. After about a week, he left for Delhi. He had lots of boxes full of papers with him. In Delhi, it is learnt he contacted Mahatma Gandhi, to whom he gave a certain note on Gilgit, probably on the lines that Gilgit should remain under the Indian government or that of Pakistan. It is further learnt a copy of that note was passed on by him to Pakistan’s deputy high commissioner. He then reportedly left for Kalimpong, as his address there was “Care of Mrs Shariff, Tashiding”.

As we now know, Pakistan got possession of Gilgit-Baltistan through the connivance of two British military officers. In 1935, the Gilgit agency was leased for 60 years by the British from the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir because of its strategic location on the northern borders of British India. It was administered by the political department in Delhi through a British officer. With impending Independence, the British terminated the lease, and returned the region to the Maharaja on August 1, 1947.

The Maharaja appointed Brig. Ghansara Singh of the J&K state forces as governor of the region. Two officers of Gilgit Scouts, Maj. W.A. Brown and Capt. A.S. Mathieson, along with Subedar Major Babar Khan, a relative of the Mir of Hunza, were loaned to the Maharaja at Gilgit. But as soon as Maharaja Hari Singh acceded to India on October 26, 1947, Maj. Brown imprisoned Brig. Ghansara Singh, and informed his erstwhile British political agent, Lt. Col. Roger Bacon, who was then at Peshawar, of the accession of Gilgit to Pakistan. The conspiracy saw Maj. Brown on November 2 officially raising the Pakistani flag at his headquarters, and claimed he and Mathieson had opted for service with Pakistan when the Maharaja signed the Instrument of Accession in favour of India.

Earlier, Mainprice had arrived in Srinagar on June 13, 1948. He stayed for some time at Nedous Hotel, then moved into a houseboat. From the beginning, his activities came under the notice of the police. He visited Bandipur, Baramulla and Sopore in the beginning, and then at Baramulla tried to take some photographs and came under the Army’s notice. He was eventually stopped from doing so. He came into very close contact with Dr Edmunds, principal of the local missionary high school, who was incidentally known for his pro-Pakistan sympathies.

Remember this was an extremely fluid and dangerous time. He accompanied him to Mahadev on a trekking expedition. During his stay in Srinagar, he had a close association with Capt. Annette and other Europeans, who were also seemingly pro-Pakistan. He tried to establish contact with local people and was observed trying to get information from them on military movements and the working of the government. It seemed his purpose of staying on in Srinagar was to wait for United Nations Kashmir Commission to arrive and to supply them with data. During the commission’s stay in Srinagar, he first tried to approach the commission, in which he did not succeed, but then contacted Mr Symonds, secretary to the commission, and also he tried through his other European friends to influence the commission through Mr Symonds in favour of the state’s accession to Pakistan.

When his activities got absolutely objectionable, the government was forced to pass an order against him under the Defence Rules to leave the state, but he refused to obey it, calling it a ridiculous and scandalous order. However, under the Defence Rules, the DIG, Kashmir Range, was deputed to inform him he would have to leave the state, and if he refused to do so he would be forced to leave and put on the aircraft. When the DIG reached his houseboat, he was found to be absent and closeted with Capt. Annette in the latter’s boat. He was sent for by the DIG and told he had to leave that day, as the time limit given to him was about to expire. To this he replied that he was not going. The DIG told him the order would have to be carried out and he would have to leave.

At this Mainprice got excited and made a sudden assault on the DIG, knocking off his hat and spectacles, and tried to grapple with other police officers. However, he was overpowered and driven to the airport, where he was put on a plane bound for Delhi. After he left, a magistrate was asked to make an inventory of all his belongings, so that these could be handed over to Capt. Annette, in accordance with Mainprice’s wishes. While making this inventory, some papers were found that indicated Mainprice had been busy writing a note on the happenings in Jammu in a very exaggerated manner, and also a note on the history of Kashmir, including Gilgit; possibly for the benefit of the commission on how the state actually came under Dogra rule.

He also seemed to be trying to compile a census of the population of different communities in various districts of the state. He was busy telling people that he was private secretary to Sir Walter Monckton, constitutional adviser to His Exalted Highness the Nizam of Hyderabad (one of those opposed to the unification of India and the merger of the princely states with the two dominions). He was also expressing a desire to be closely associated with the UN commission on Kashmir to give them all the information he had collected.

Further, it was discovered he had some links with a certain Anglo-Indian officer of the Royal Indian Air Force, and through him had managed to take some aerial photographs of the state of J&K. It was thus obvious how Mainprice, like so many other assorted characters who were floating around after the British had officially handed over India to Indians, continued to obfuscate and frustrate us.

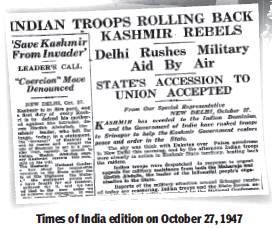

1947, Oct 23-26

August 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 6, 2019: The Times of India

From: August 6, 2019: The Times of India

The Four Eventful Days That Decided The Fate of Kashmir

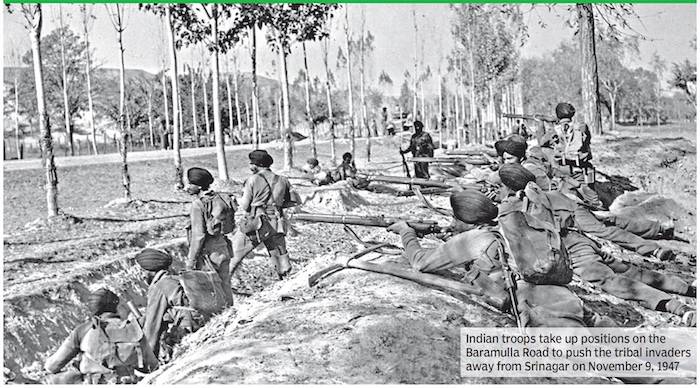

1 RAID ON KASHMIR (the final week of October 1947)

The attack on Kashmir by Pathan tribesmen was masterminded by Pakistan army and led by senior Pakistan army officer Akbar Khan. The British had succeeded in forging an uneasy peace with the tribes of the North-West Frontier but after the British withdrew, Pakistan incited the tribesmen into launching their attack. By the last week of October 1947, about 5,000 had entered Kashmir

2 INVADERS’ ROUTE (October 23)

The tribesmen transited through Pakistan carrying modern military gear. The first standoff was at Muzaffarabad where they faced a battalion of Dogra troops, capturing the bridge between Muzaffarabad and Domel, which itself fell to the attackers the same day. Over the next two days, they took Garhi and Chinari. The main group of attackers then proceeded towards Uri

3 THE GALLANT 300

At Uri, Brigadier Rajinder Singh, who led J&K state forces, was killed. “He and his colleagues will live in history like the gallant Leonidas and his 300 men who held the Persian invaders at Thermopylae,” writes civil servant VP Menon. The battle at Uri holds significance as it likely helped Maharaja Hari Singh avoid capture and bought the Indian government valuable time to bring in more forces. After the battle, the tribesmen travelled down the Jhelum river to Baramulla, the entry point into the Valley

4 THE FLIGHT OF HARI SINGH (October 24-25)

On October 24, the maharaja made an urgent appeal to the Indian government. He waited for a response, while the Cabinet’s defence committee met in Delhi.VP Menon, administrative head and secretary of the states department, was instructed to fly to Srinagar on October 25. Menon’s first priority was to get the maharaja and his family out of Srinagar. There were no forces left to guard the capital and the invaders were at the door. The king left the Valley by road for Jammu

5 TROOPS INDIAN FLY INTO THE VALLEY

On October 26, after a Cabinet defence committee meeting, the government decided to fly two companies of troops to Srinagar. Menon himself took a plane to Jammu where the king was stationed

6 SIGNING OF INSTRUMENT OF ACCESSION (October 26)

Governor-general Mountbatten had contended it would be the “height of folly” to send troops to a neutral state without an accession completed “but that it should only be temporary prior to a referendum.” Neither Nehru nor Sardar Patel attached any importance to the “temporary” clause, but Menon was carrying a message for the maharaja: he had to join the Union if he wanted to ward off the invasion. The king was ready to accede. In fact, according to Menon’s memoirs, he had left word with an aide that if Menon did not return with an offer, he was to shoot the king in his sleep. Hari Singh signed the accession letter regretting that the invasion had left him with no time to decide what was in the best interest of his state, to stay independent or merge with India or Pakistan

7 FINAL ACT (October 27)

Menon returned to Delhi on October 27 with both the letter and Instrument of Accession. The Cabinet defence committee accepted the accession, subject to a provision that a referendum would be held in the state when the law and order situation allowed it. Sheikh Abdullah took charge of an emergency administration in Kashmir. Nehru appointed the former Kashmir PM N Gopalswamy Ayyangar as a cabinet minister to look after Kashmir affairs. Ayyangar was one of the chief architects of Article 370

Source: Kashmir in Conflict by Victoria Schofield, The Story of the Integration of the Indian States by VP Menon

1947, Sept

Nehru links accession to the installation of popular government in J&K

Chandrashekhar Dasgupta, Dec 16, 2022: The Indian Express

Nehru had been urging the Maharaja to induct Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of the secular National Conference, into the state government in order to ensure popular support for the administration. The Maharaja indicated that he was not prepared to do so

Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir was one of the few princely rulers who had held out against accession to either India and Pakistan before the partition of British India. In June 1947, a couple of months prior to the partition, the Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, visited Srinagar in an attempt to persuade the Maharaja to opt for one or the other of the two states, offering him an assurance from Sardar Patel that India would raise no objection if the ruler were to opt for Pakistan. The Maharaja entertained his guest in regal style but evaded any discussion on the political issue, pleading a stomach ailment. Hari Singh evidently hoped that, with the lapse of British paramountcy, he would become the ruler of an independent and sovereign state.

These hopes were dashed shortly afterwards by two developments — an uprising in Poonch assisted by Pakistani elements and an undeclared economic embargo imposed by the Pakistani authorities. Since Kashmir’s main trade exchanges in those days were with Pakistan, the unofficial embargo resulted in great hardship.

At this stage, the Maharaja revised his position on accession. He asked Justice Mehr Chand Mahajan, his prime minister-designate, to convey to Nehru the terms on which he was prepared to accede to India. The Maharaja was not agreeable to introducing immediate reforms in the administration of the state. Nehru had been urging the Maharaja to induct Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of the secular National Conference, into the state government in order to ensure popular support for the administration. The Maharaja indicated that he was not prepared to do so, at least at this stage. When Mahajan conveyed these terms to Nehru in the third week of September, the latter reiterated that Abdullah should be freed from prison and associated with the governance of the state.

Why did Nehru insist on bringing Sheikh Abdullah into the administration? Nehru anticipated armed intervention by Pakistan in Kashmir and foresaw that this could be repulsed only by a government that enjoyed popular support. He set out his views in a letter to Sardar Patel on September 27, 1947, nearly a month before the tribal invasion. This remarkable letter has not received the attention it deserves. “The Muslim League in the Punjab and the NWFP are making preparations to enter Kashmir in considerable numbers. The approach of winter is going to cut off Kashmir from the rest of India,” he wrote. “I understand that the Pakistan strategy is to infiltrate into Kashmir now and to take some major action as soon as Kashmir is more or less isolated because of the coming winter… I rather doubt if the Maharaja and the State forces can meet the situation by themselves without some popular help… Obviously the only major group that can side with them is the National Conference under Sheikh Abdullah’s leadership.”

Nehru, therefore, concluded that the only acceptable course was for the Maharaja to seek the cooperation of Sheikh Abdullah and the National Conference while acceding to India. This was the only effective way of countering Pakistani designs.

We must also recall that developments in Kashmir were unfolding against the backdrop of Junagadh. On August 15, the Nawab of Junagadh had acceded to Pakistan and subsequent events had demonstrated the folly of taking such decisions without popular support. In this context, India proposed to Pakistan on September 30 that all cases of disputed accession should be settled by a plebiscite or referendum. This was the course India followed in Junagadh and it had obvious implications also for Kashmir.

Why did Nehru insist on bringing Sheikh Abdullah into the administration? Nehru anticipated armed intervention by Pakistan in Kashmir and foresaw that this could be repulsed only by a government that enjoyed popular support. He set out his views in a letter to Sardar Patel on September 27, 1947, nearly a month before the tribal invasion. This remarkable letter has not received the attention it deserves. “The Muslim League in the Punjab and the NWFP are making preparations to enter Kashmir in considerable numbers. The approach of winter is going to cut off Kashmir from the rest of India,” he wrote. “I understand that the Pakistan strategy is to infiltrate into Kashmir now and to take some major action as soon as Kashmir is more or less isolated because of the coming winter… I rather doubt if the Maharaja and the State forces can meet the situation by themselves without some popular help… Obviously the only major group that can side with them is the National Conference under Sheikh Abdullah’s leadership.”

Nehru, therefore, concluded that the only acceptable course was for the Maharaja to seek the cooperation of Sheikh Abdullah and the National Conference while acceding to India. This was the only effective way of countering Pakistani designs.

We must also recall that developments in Kashmir were unfolding against the backdrop of Junagadh. On August 15, the Nawab of Junagadh had acceded to Pakistan and subsequent events had demonstrated the folly of taking such decisions without popular support. In this context, India proposed to Pakistan on September 30 that all cases of disputed accession should be settled by a plebiscite or referendum. This was the course India followed in Junagadh and it had obvious implications also for Kashmir.

It is significant that at the end of the 1947-48 war, the areas on our side of the Kashmir ceasefire line were, broadly speaking, the areas where the National Conference enjoyed wide support.

Far from being a blunder, Jawaharlal Nehru’s insistence on linking accession to the installation of a popular government in Jammu and Kashmir bears testimony to his foresight and statesmanship.

1947, Oct-Nov

‘Standstill agreement’ with India and Pakistan

Oct 10, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 10, 2021: The Times of India

From: Oct 10, 2021: The Times of India

The princely state of Jammu & Kashmir, a Muslim-majority state led by a Hindu ruler, was among only a handful that chose against joining either India or Pakistan after Independence. J&K shared borders with both newly formed countries, making it a key strategic region. So when Maharaja Hari Singh — who wanted J&K to be the “Switzerland of the East” — refused to accede to either dominion, the state became another early source of instability as India grappled with the violence stemming from Partition and other obstinate princes.

Just days ahead of Independence, Singh sought a ‘standstill agreement’ with India and Pakistan, which would temporarily maintain its existing agreements with the British government. Pakistan signed on but India refused. While Pakistan believed that signing the standstill agreement would eventually result in J&K joining it, India held out hope that its strong ties to popular local leaders like National Conference founder Sheikh Abdullah and Jawaharlal Nehru’s Kashmiri roots would lead to accession in its favour.

But the stalemate continued through October amid growing strife within J&K. Despite signing the standstill agreement, Pakistan urged Singh to accede to it, saying failing to do so would lead to “gravest possible trouble”. J&K complained of Pakistani incursions across the border but Pakistan shot back accusing the princely state of making incursions into Sialkot. At the same time, an anti-establishment campaign in Poonch turned into a secessionist movement to join Pakistan. As relations with the maharaja worsened, Pakistan began to fear the princely state would accede to India, prompting a military operation to take J&K by force.

On October 22, 1947, Pakistan launched ‘Operation Gulmarg,’ sending in thousands of Pathan tribal fighters across the North-West Frontier Province into J&K. Singh was ill-prepared to fend off the raiders, who descended into the Jhelum valley, taking Uri and Baramulla, and cutting off power supply to Srinagar. Left with no other choice, on October 24, Singh sought assistance from India. On October 25, India’s Defence Committee recommended swift action against the raiders while Lord Louis Mountbatten, India’s last viceroy, said intervention should be conditional on accession. As tribal fighters neared Srinagar, Singh signed the Instrument of Accession on October 26. India then airlifted troops to Srinagar, and defended the capital and repelled the raiders. The fighting carried on through November with Indian forces pushing the tribal fighters as far back as Uri until the arrival of winter snows.

In January 1948, India took the matter to the United Nations, hoping it would help clear the Pakistani occupation in northern J&K. But in May 1948, the first Indo-Pakistan war broke out with Pakistan sponsoring a government of ‘Azad Kashmir’ across what is now the Line of Control. In August 1948, the UN passed a resolution calling for a ceasefire, withdrawal of troops and a plebiscite. The ceasefire was agreed to on January 1, 1949, bringing an end to hostilities after more than a year.

Mehr Chand Mahajan (month not stated, perhaps Oct)

Sugata Srinivasaraju, Dec 20, 2022: The Times of India

If there is a highly credible eyewitness account that survives as to how the Maharaja of Kashmir finally signed the accession treaty with India, and how the principal players of the time from Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru, Sardar Patel, Jinnah and Sheikh Abdullah moved their Kashmir cards, it is to be found in this book.

To the blame game that constantly erupts between the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Congress on the role of Nehru in Kashmir, this autobiographical work can play a neutral umpire. It offers a blow-to-blow account of an insider who highlights the precocious, yet impatient role played by Nehru. Justice Mahajan was negotiating with Nehru directly, on behalf of Maharaja Hari Singh.

The neutrality of the account is somewhat established when it does not offer a positive portrait of Sheikh Abdullah, Nehru’s friend and ally: “This was my first good look at Sheikh Abdullah and my impression was that he was out to gain power at any cost. To acquire it he would try to influence his friend, the Prime Minister of India, but would not disdain the use of any other means such as creating some kind of uprising in the State.”

One particular episode, when Mahajan is seeking military help from Nehru to ward off Pakistani raiders is interesting. It shows how Nehru was deeply invested and dependent on Sheikh Abdullah to get Kashmir to accede to India: “As a last resort I said, ‘Give us the military force we need. Take the accession and give whatever power you desire to the popular party [National Conference]. The army must fly to save Srinagar this evening or else I will go to Lahore and negotiate terms with Jinnah.’ When I told the Prime Minister of India that I had orders to go to Pakistan in case immediate military aid was not given, he naturally became upset and in an angry tone said, ‘Mahajan, go away.’ I got up and was about to leave the room when Sardar Patel detained me by saying in my ear, ‘Of course, Mahajan, you are not going to Pakistan.’ Just then, a piece of paper was passed over to the Prime Minister, he read it and said in a loud voice, ‘Sheikh Sahib also says the same thing.’ It appeared Sheikh Abdullah had been listening to all this talk while sitting in one of the bedrooms adjoining the drawing room where we were.”

The Lahore question

As insightful and interesting in the book are Mahajan’s exchanges with Radcliffe on the Boundary Commission that partitioned India: “I myself did not know what the award of Lord Radcliffe would be [because all four judges on the commission had disagreed and had written separate reports and Radcliffe as head had to arbiter the final award] but I had some hope on the basis of the talks and arguments that I had with him for a whole day that Lahore might remain in India. But while we were discussing the award at the hotel, Lord Radcliffe had once exclaimed: ‘How can you have both Calcutta and Lahore?

What can I give to Pakistan?’ I protested against this non-judicial observation. Thereafter throughout our talk he seemed to agree to most of my arguments when I urged that Lahore should be included in India and not in Pakistan. It was on this basis that I told some people who came to see me on the 9th of August that there was some likelihood of Lahore remaining in India…Most of the Hindus and Sikhs in Punjab had hypnotized themselves into belief that Lahore would remain in India.”

There is no reference to the Karnataka-Maharashtra border dispute because the book stops at 1963.

This enormously accomplished man, whose birth anniversary happens to fall on December 23, was declared as “highly inauspicious” by astrologers at birth and was given away to a poor peasant family. He was born to a rich family of Mahajan Sahukars: “When I became four years old I was assigned the duties that a peasant boy has to perform, look after the family goats and sheep, take the cattle for grazing, sit on the water mill and the furrows.” He was accepted back by his original family after he turned 12. The partitions of his own life, it appears, were equally wrenching.

When did the Indian army intervene?

The government of India offered a temporary accession and promised to carry out a referendum later on, ensuring that India would control external affairs, defence and communications in J&K. Indian troops were airlifted into Srinagar on October 27, 1947. The fighting continued for over a year and in 1948 Jawaharlal Nehru asked the UN to intervene. A UN ceasefire was declared from December 31, 1948. By now, two-thirds of the state was under the control of India, while one-third came under Pakistan’s control. The ceasefire was laid out by a UN resolution requiring Pakistan to withdraw its troops while India was allowed to keep its forces to maintain law and order in the state. A plebiscite was supposed to take place once peace was restored.

UN intervention in 1948

UN intervention in 1948 gave J&K its present shape

UN intervention in 1948 gave J&K its present shape

The Times of India, Oct 17, 2011

From the Durranis and Mughals, the Kashmir Valley passed to the Sikh rulers who conquered the region in the early 19th century. Gulab Singh played a vital role in this campaign and Maharaja Ranjit Singh made him the king of Jammu. Later, Gulab Singh captured Ladakh and Baltistan and merged them into Jammu. After the first Anglo-Sikh war, the Sikhs ceded Kashmir, Hazarah and all the hilly regions between the Indus and Beas to the East India Company. In 1846, Gulab Singh and the company signed a treaty in which he purchased the Valley from the British.

What happened in 1947?

After Independence, the princely states were given the option of joining India or Pakistan. The ruler of J&K, however, delayed his decision. He was a Hindu while a majority of his subjects were Muslims. In October 1947, ‘tribals’ from Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province, supported by the Pakistan army invaded J&K, instigating communal clashes between Hindus and Muslims in the state. Unable to control the situation, the king requested India for armed assistance.

Why did the plebiscite never take place?

Both sides blame each other for that. While Pakistan blames India for not carrying out the referendum, India counters by saying that Pakistan never withdrew its forces, thereby making it impossible for India to hold a referendum in the entire territory.

Sangh’s stand on J&K plebiscite

A month-long exhibition on J&K, which opened at the National Archives on Thursday, seeks to highlight just how the founding president of Jan Sangh, Syama Prasad Mookerjee, warned former PM Jawaharlal Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah about the far reaching consequences of the signing of Kashmir’s Instrument of Accession.

Drawing from documents and videos obtained from the ministry of defence, the films division and the British Pathe, the exhibition includes rare documents like The Treaty of Lahore of March, 1846, The Treaty of Amritsar, and the Instrument of Accession signed in October 1947. The exhibition also contains a section titled ‘Syama Prasad Mookerjee on J&K issue and on the agitation which sought full integration of the state with India’.

Four letters written by Mookherjee, two each to Nehru and Sheikh Abdullah, are also on display. In one such letter to Nehru on January 9, 1953, Mookerjee wrote, “It is high time that both you and Sheikh Abdullah should realise that this movement will not be suppressed by force or repression...The problem of J&K should not be treated as a party issue. It is a national problem and every effort should be made to present a united front.”

Warning against the dangers of a “general plebiscite on a highly controversial issue”, Mookerjee also predicted the rise of communal passions in J&K. His letter to Abdullah also exposes the schism between the Jan Sangh and the National Conference over the rule of J&K shifting hands from the ‘Hindu Dogras’ to the ‘Kashmiri Muslims’. In a letter dated February 13, 1953, Mookerjee refers to Abdullah’s opposition to Praja Parishad, a political outfit with close ties with

the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, and which campaigned for the integration of Jammu & Kashmir with India, and opposed the special status granted to the state under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution.

Inaugurating the exhibition, culture minister Mahesh Sharma said the purpose of curating the exhibition is to educate the youth about how Kashmir became a part of India. “Maharaja Hari Singh, when he signed this instrument (of accession), only after that, I repeat, only after that, the Indian forces went to that area. This needs to be showcased,” Sharma said.

Why India sought UN intervention

March 27, 2022: The Indian Express

It is well documented that both the British government and Lord Mountbatten, who was the first Governor General of India after Independence from August 15, 1947 to June 21, 1948, believed that the then newly-founded UN could help resolve the Kashmir dispute. Mountbatten suggested this to Muhammad Ali Jinnah at a meeting between the two men in Lahore on November 1, 1947.

After Nehru met Liaquat Ali Khan in Lahore the following month, Mountbatten was convinced that an intermediary was needed. He recorded his views: “I realised that the deadlock was complete and the only way out now was to bring in some third party in some capacity or other. For this purpose I suggested that the United Nations Organisation be called in.” (Victoria Schofield, ‘Kashmir in Conflict’, quoting Mountbatten in H V Hodson, ‘The Great Divide’)

Reference to UN

Initially, while Liaquat “agreed to refer the dispute to the UN”, Victoria Schofield wrote in her seminal history of the Kashmir dispute, “India was not prepared to deal with Pakistan on an equal footing”. However, “when the two prime ministers met again in Delhi towards the end of December [1947], Nehru informed Liaquat Ali Khan of his intention to refer the dispute to the UN under article 35 of the UN Charter…”.

Consequently, on December 31, 1947, Nehru wrote to the UN secretary general (then Trygve Lie of Norway) accepting a future plebiscite in Jammu and Kashmir.

He said: “To remove the misconception that the Indian government is using the prevailing situation in Jammu and Kashmir to reap political profits, the Government of India wants to make it very clear that as soon as the raiders (Pakistan-backed tribesmen who had entered the Kashmir Valley) are driven out and normalcy is restored, the people of the state will freely decide their fate and that decision will be taken according to the universally accepted democratic means of plebiscite or referendum.”

Issue in the UN

The UN Security Council took up the matter in January 1948. The jurist Sir Zafrullah Khan spoke for five hours in favour of the Pakistani position. India was unhappy with the role played by the British delegate, Philip Noel-Baker, who it believed was nudging the Council towards Pakistan’s position. V Shankar, private secretary to Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, noted in his unpublished memoirs (quoted in Schofield):

“The discussions in the Security Council on our complaint of aggression by Pakistan in Jammu and Kashmir have taken a very unfavourable turn. Zafrullah Khan had succeeded, with the support of the British and American members, in diverting the attention from that complaint to the problem of the dispute between India and Pakistan over the question of Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan’s aggression in the State was pushed into the background due to his aggressive tactics…as against the somewhat meek and defensive posture we adopted to counter him.”

On January 20, 1948, the Security Council passed a resolution to set up the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) to investigate the dispute and to carry out “any mediatory influence likely to smooth away difficulties”.

There is evidence to believe Sardar Patel was uncomfortable with Nehru taking the matter to the UN, and thought it was a mistake. “…Not only has the dispute been prolonged, but the merits of our case have been completely lost in the interaction of power politics,” he wrote. (July 3, 1948, quoted in Schofield)

Article 35 of UN Charter

There has been some debate on whether India chose the wrong path to approach the UN. In 2019, Home Minister Amit Shah said that had Nehru taken the matter to the UN under Article 51 of the UN Charter, instead of Article 35, the outcome could have been different.

According to UN records, India reported to the Security Council “details of a situation existing between India and Pakistan owing to the aid which invaders, consisting of nationals of Pakistan and tribesmen from the territory immediately adjoining Pakistan on the north-west, were drawing from Pakistan for operations against Jammu and Kashmir”.

India pointed out that J&K had acceded to India, and that the “Government of India considered the giving of this assistance by Pakistan to be an act of aggression against India…” Therefore, “the Government of India, being anxious to proceed according to the principles and aims of the Charter, brought the situation to the attention of the Security Council under Article 35 of the Charter.”

Articles 33-38 of the UN Charter occur in Chapter 6, titled “Pacific Settlement of Disputes”.

These six Articles lay out that if the parties to a dispute that has the potential for endangering international peace and security are not able to resolve the matter through negotiations between them, or by any other peaceful means, or with the help of a “regional agency”, the Security Council may step in, with or without the invitation of one or another of the involved parties, and recommend “appropriate procedures or methods of recommendation”.

Specifically, Article 35 only says that any member of the UN may take a dispute to the Security Council or General Assembly.

Article 51, which occurs in Chapter 7, titled “Action With Respect to Threats to the Peace, Breaches of the Peace, and Acts of Aggression”, on the other hand, says that a UN member has the “inherent right of individual or collective self-defence” if attacked, “till such time that the Security Council has taken measures necessary to maintain international peace and security”.

Nehru’s role

A

Adrija Roychowdhury, Oct 13, 2022: The Indian Express

Kashmir before Independence

When the British decided to exit the Indian subcontinent, the fate of the 500-odd princely states was yet to be decided. The Congress had announced its decision of integrating the princely states within the Indian union by the late 1930s itself. Consequently, a new states department was set up with Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel as its head and V P Menon as the secretary. They worked together under the guidance of Lord Mountbatten to strategise and convince the princely states to accede to the Indian union.

Of the 500 princely states, the most important was Jammu and Kashmir. It was the largest in India and also the most strategically located, sharing borders with both the newly born dominions of India and Pakistan. The state with a predominantly Muslim population was being ruled by Maharaja Hari Singh, a Dogra king who ascended the throne in September 1925. The king, however, is known to have spent most of his time in race courses and hunting.

By the 1930s, the Kashmiri political scene saw the emergence of Sheikh Abdullah, son of a shawl merchant, who graduated from Aligarh Muslim University with a degree in science. Abdullah’s inability to find a government job in Kashmir led him to question the treatment of Muslims in the state administration which was dominated by Hindus. “We constituted the majority and contributed the most towards the state’s revenues, still we were continually oppressed…I concluded that the ill-treatment of Muslims was an outcome of religious prejudice,” he is known to have said as quoted by historian Ramachandra Guha in his book, ‘India after Gandhi’.

In 1932, Abdullah along with other Muslims of the state opposed to the ruler formed the All-Jammu Kashmir Muslim Conference that later became the ‘National Conference’. It consisted of Hindus and Sikhs apart from Muslims, and demanded a representative government based on universal suffrage. During this time, Abdullah came into contact with Jawaharlal Nehru and they warmed to each other instantly, mainly on account of their shared ideological commitment to Hindu-Muslim harmony and socialism.

Through the 1940s, Abdullah’s popularity in Kashmir kept increasing. He demanded the Dogra dynasty to quit Kashmir, and the Maharaja responded by sending him to jail on more than one occasion. In 1946 when he was sentenced to three years imprisonment for sedition, Nehru rushed to his rescue, but was prevented from entering the state by the Maharaja’s men.

The accession of Kashmir to India

When the question of Kashmir’s accession to India or Pakistan arose, the Maharaja made clear his intention of remaining independent. “He loathed the Congress, so could not think of joining India. But if he joined Pakistan the fate of the Hindu dynasty might be sealed,” wrote Guha. The Maharaja disliked Nehru, who was openly supporting Abdullah’s ‘Quit Kashmir’ movement.

But for Nehru, the issue of Kashmir was a most crucial one. While the responsibility of convincing the states to join India was left in the hands of Patel, a task that he performed with near full autonomy, in the case of Kashmir, Nehru was personally involved.

Geographer Simrit Kahlon in her article, ‘Kashmir and Nehru: Contours of a troubled legacy’ (2020) noted Nehru’s fondness for Kashmir in his writings which included both his personal and well as official correspondence. In a letter to Abdullah in September 1947, Nehru wrote, “For me Kashmir’s future is of the most intimate personal significance.”

In the days preceding Independence, however, it was Mountbatten who tried to convince the Maharaja to accede to India. An old acquaintance of the Maharaja, he set off for Kashmir in June 1947, largely to forestall Nehru or Gandhi from doing so. In Srinagar, Mountbatten first met the prime minister Ramchandra Kak, who reiterated the state’s decision to remain independent. Mountbatten then fixed a private meeting with the Maharaja on the last day of his visit. However, on the day of the appointment, Hari Singh stayed in bed with an attack of colic, most probably a way to avoid the encounter. Hari Singh’s son, Karan Singh, in his autobiography has described this decision of his father to avoid meeting Mountbatten as a “typical feudal reaction to a difficult situation”. “Thus the last real chance of working out a viable political settlement was lost,” he wrote.

On August 15, Kashmir had neither acceded to India or Pakistan, but it offered to sign standstill agreements with both countries to allow movement of people and goods across borders. While Pakistan agreed to sign the agreement, India decided to wait and watch. However, Kashmir’s relations with Pakistan began deteriorating as the latter expected its accession on account of a largely Muslim population.

Guha in his book noted that while Nehru always wanted Kashmir to be part of India, Patel at one time was inclined to allow the state to join Pakistan. But he changed his mind on September 13, when Pakistan decided to accept the accession of Junagadh, a Hindu-majority state in the Kathiawar region with a Muslim ruler.

On September 27, Nehru wrote to Patel about the ‘dangerous and deteriorating’ situation in Kashmir and that there were rumours of Pakistan preparing to send infiltrators. He also wrote that releasing Abdullah was a necessity now to ensure popular support for the Maharaja.

Soon after Abdullah was released, he announced his demand for a popular government in Kashmir consisting of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims. The Maharaja, on the other hand, was still harbouring thoughts of an independent government. “The only thing that will change our mind is if one side or the other decides to use force against us,” he is known to have said.

Two weeks later, several thousand armed men crossed into the state from the north, making their way to the capital. The fact that these were Pathans from Pakistan has remained undisputed, but why they came and on whose orders has remained at the heart of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. While India believed that these were Pakistani infiltrators sponsored by the state, Pakistan denied any involvement. They claimed that these were Pathans who rushed to the aid of Muslims in Kashmir being persecuted by a Hindu administration.

As the tribesmen marched on killing and looting everything in sight on their way to Srinagar, the Maharaja wired the Indian government for military assistance. On October 25, V P Menon flew down to Srinagar and advised Singh to move to Jammu for his safety. Once Menon flew back to Delhi, a Defence committee meeting was convened consisting of Nehru, Mountbatten, Patel and Abdullah. It was decided that India would immediately send troops to Kashmir, but before that it would secure Hari Singh’s accession to India. The following morning, Menon flew to Jammu where the Maharaja had taken refuge. The Maharaja, exhausted from his turbulent escape, agreed to sign the instrument of accession immediately.

From October 27, several planes carrying Indian soldiers and supplies left from Delhi to Srinagar to fight back the infiltrators and restore peace in the valley.

Kashmir after accession

The entry of Indian troops into Kashmir left the Pakistan government fuming. When Mountbatten met Jinnah in Lahore in November 1947, the former described Kashmir’s accession to India as being based on ‘fraud and violence’. Mountbatten, however, suggested that the aggression had come from raiders from Pakistan.

With the Indian military securing Srinagar and clearing infiltrators from the other parts of the valley, the focus of the Indian government shifted to the internal politics of Kashmir. Nehru wrote to Singh asking him to place full confidence in Abdullah and make him head of the administration. With the support of Gandhi, Nehru was able to get Abdullah appointed as head of an emergency administration by the Maharaja.

As far as the impasse with Pakistan was concerned, Nehru suggested a plebiscite be conducted to decide on which dominion the people of the state wanted to join. Guha noted in his book that Nehru was also open to an independent Kashmir or the state being divided with Jammu and the valley being with India and the rest of the territory going to Pakistan.

With no decision being taken on the matter, On January 1, 1948, India decided to take the Kashmir issue to the United Nations on the advice of Mountbatten who was then the governor-general of India. But at the UN, India was surprised to see the British support for the Pakistan position. Nehru deeply regretted taking the matter to the international stage. Meanwhile, the Pakistan and Indian armies engaged in battle through the later months of 1948 in the northern and western parts of Kashmir.

Abdullah, who had by now become the most important political figure in Kashmir, insisted on the ties that Kashmir shared with India. In May 1948 he organised a weeklong celebration of freedom in Srinagar, in which several leading figures of the Indian government were invited.

B: ‘Nehru consulted his generals,’ say papers declassified in 2023

Anisha Dutta, 8 Mar 2023: The Guardian

India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was urged by his most senior general to agree to a ceasefire with Pakistan in 1948, the Guardian can reveal after viewing letters on Kashmir that have been kept classified in India for decades.

The correspondence from the then commander-in-chief, Gen Sir Francis Robert Roy Bucher, will have significant political ramifications for the current nationalist government in Delhi, which has discredited Nehru’s decision to come to a compromise on the status of disputed Kashmir as an ill-informed “blunder”.

Narendra Modi’s government has used that reasoning to justify stripping Kashmir of special status in 2019 and tightening its grip over the region.