Lucknow: A-E

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

This article was written in 1939 and has been extracted from

HISTORIC LUCKNOW

By SIDNEY HAY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ENVER AHMED

With an Introduction by

THE RIGHT HON. LORD HAILEY,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E.

Sometime Governor of the United Provinces

Asian Educational Services, 1939.

Contents |

The Alam Bagh

Compared With Many Of The historic buildings in and around Lucknow, the Alam Bagh on the Cawnpore Road is relatively modern, for it was built by Wajid Ali Shah, the last King of Oudh, who reigned from 1847 to 1856. It was built as a country residence for one of his favourite wives, but it is hard to realise that a pleasant garden once covered the dreary waste now surrounding the ruins of a compact house. Each of the four corners is ornamented by an octagonal tower, on one of which a semaphore post established the only means of communication with the beleaguered garrison in the Residency in 1857.

The house consists of two storeys, and there is not a single window in the entire building. A battered brick wall surrounds the erstwhile garden, and both it and the solid square entrance gate still show great holes where the enemy made repeated attacks upon the gallant little force pressing on to relieve their comrades pent up in the Residency. On July 7, 1857 Havelock proceeded with a small force of 1,400 British and 550 Indians to the relief of Lucknow. An Indian pensioner named Ungud got through the besieging force several times, carrying letters from Brigadier Inglis (who by that time was in command at the Residency owing to the death of Sir Henry Lawrence) to Sir Henry Havelock at the Alam Bagh. On July 25, Havelock sent Ungud back to the Residency with a letter saying, “We have two-thirds of our force across the river, and eight guns in position already.

The rest will follow immediately. We have ample force to destroy all who oppose us..….” This struck an unduly optimistic note and after five great actions had been fought and won, Havelock’s losses were so severe that he decided to fall back to Cawnpore on August 17. Havelock was then superseded by Sir James Outram. The country people said of him: “A fox is a fool and a lion is a coward by the side of Outram Sahib.”

On September 23, the column again sighted the Alam Bagh but found it strongly held by about 10,000 trained sepoys and many guns. From there, crossing the Cawnpore Road and extending for some two miles, stretched a line of hostile troops, the centre upon rising ground and the right flank lying behind a marshy swamp. The rebels had concentrated the bulk of their troops in the A lam Bagh and were taken completely by surprise when Havelock sent his second Brigade through the heavy marsh land.

Eyre’s heavy battery crashed up the road, while Major Olpherts’ battery galloped along to cover the advance of the 2nd Brigade, amid the cheers of the 1st Brigade. Soon they had to leave the road and cross a deep ditch filled, with water. The cavalry escort crossed it without much difficulty and halted for the guns, “Hell-Fire Jack” Olpherts was not to be beaten.

For a moment there was chaos : a wild medley of detachments, drivers, guns, struggling horses and splashing water ; and then the guns were on the further side, nobody and nothing the worse for the scramble, all hands on the alert to obey Olpherts’ shout, “Forward, gallop.” The enemy, taken by surprise, fled in confusion and the force attacking the Alam Bagh, reinforced by the 5th Fusiliers on the south side and the 78th at the main entrance, carried it with a rush. A Malacca cane was Outram’s only weapon and brandishing it he led the pursuit of the enemy for several miles. That night news was received of the fall of Delhi, which raised still higher the soldiers’ spirits, although afterwards the report was found to be erroneous.

The next move was to be via the Sikandra Bagh to the Residency, leaving Major McIntyre of the 78th at Alam Bagh, in charge of 280 European soldiers, a few Sikhs, four guns, about 130 sick and wounded, some 4,000 native followers, the baggage, the reserve food, and the ammunition. Although they fought no actual engagement, the rebel cavalry was always skirmishing round and it was a relief when on October 7 a reinforcement arrived from Cawnpore consisting of two hundred men and two guns, and later on five hundred infantry, fifty cavalry and two more guns appeared.

On November 6, the sick and wounded were removed to Cawnpore under the escort of a strong force. Four days later Kavanagh made his famous journey out of the Residency to the Alam Bagh thereby gaining the Victoria Cross. Although his wife and children were in the Residency, he volunteered to make his way out in disguise in order to guide the relieving force. Brigadier Inglis refused to allow him to go unless his disguise was impenetrable. Accordingly he dressed himself as an Indian, and walked boldly into the officers’ dining-room in the Residency, where he sat down uninvited and without removing his shoes—in those days two dreadful breaches of etiquette.

The officers remonstrated with him for several minutes, but until he revealed himself they did not penetrate his disguise. So he made for the river by way of the entrenchments, swam across and recrossed again by the old stone bridge. Then he walked boldly through the heart of the city full of rebel posts and finally reached the Alam Bagh. On November 12, the force encamped there was joined by more troops from Cawnpore, and at 9 a.m. on the 14th, the march towards the Residency began by way of Dilkusha and La Martinière.

On November 17, the relieving force made its way into the Residency, and before them all, untouched by the hail of bullets, ran Kavanagh. Not until his safe return was his wife told of his gallant exploit. A link with Kavanagh was severed in 1934 by the death in England of Mrs. Long, his daughter, who went through the siege at the age of eight. She was twice married, her second husband having been in the 10th Royal Hussars. Her sister who also endured the siege was still alive at that date.

On November 18, Sir Colin Campbell decided to evacuate the Residency and to leave a strong force near the Alam Bagh. Two days later Havelock fell ill and died on November 24 in a soldier’s tent in the garden of Dilkusha. The next day his remains were taken to the Alam Bagh, and buried there in the presence of the Commander-in-Chief and many officers and men.

Pending the erection of a monument, the letter “H” was cut, it is said, by Outram himself in a mango tree whose branches shaded the grave. An obelisk has since been erected there bearing his proud record, and in 1897 was added a memorial to his son, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Marshman Havelock Allen, Bt., V.C., who was killed by Afridis in the Khyber Pass.

In the same peaceful little graveyard, amongst sweet-smelling flowering shrubs, lie the remains of several other officers and men who gave their lives in those troublous years of 1857 and 1858.

Asaf-Ud-Doulah

1775-1798

Asaf-Ud-Doulah Is Remembered to this day in Lucknow for his unlimited generosity. When Shuja-ud-Doulah died in 1775, his son Mirza Amani became Nawab, assuming the name of Asaf-ud-Doulah. In the same year, he transferred his capital from Fyzabad to Lucknow and at once set on foot schemes for the aggrandisement of his new headquarters, for Lucknow was then not much more than a large village. He and his courtiers lived in the Daulat Khana behind the Taluqdars’ Hall in the Husainabad area while his other schemes were taking shape.

To him are attributed the Rumi Darwaza, the Great Imambara and the Bibiapur Kothi. The magnificence and wealth of his court enhanced his fame until it exceeded that of the Great Mogul himself, living not so far away at Delhi. Adventurers, hearing of the riches and luxury to be had almost for the asking, crowded to the court of Lucknow.

During this reign the fame and luxury of Oudh reached its zenith. No other kingdom throughout the length and breadth of India could rival it. The Nawab’s only apparent ambition was to discover how many elephants the Nizam or Tippu Sultan possessed, how valuable were their diamonds—and then to surpass them. His vast wealth was collected from the peasants who were fleeced by officials until they were put almost out of existence.

Six months after his accession Asaf-ud-Doulah ceded Jaunpur and Ghazipur to the British with an annual payment to the Company. He then applied for, and received, the services of several Europeans to officer his troops. Shortly after they had assumed command of the army a mutiny broke out and a fierce engagement was fought between 2,500 matchlockmen and 15,000 regulars. This only ended when a tumbril exploded and the rebel forces retreated, leaving 600 mutineers and 300 regulars dead on the battle-field.

Asaf-ud-Doulah heard of an enterprising young Frenchman named Claud Martin, whose inventive mind had, amongst other things, caused the first balloon in India to ascend into the air. This intrigued the Nawab who asked that Martin might be transferred to his service. The request was granted. From that time began Martin’s days of wealth., prosperity, and power. When he came to Lucknow he took over the Hayat Baksh Kothi, the present Government House, as an arsenal. There he established “a manufactory where he makes pistols and fusils both as to lock and barrel better than the best arms that come from Europe.” He was clever and a faithful servant to the Nawab, and effected many excellent reforms in the military machinery of the state.

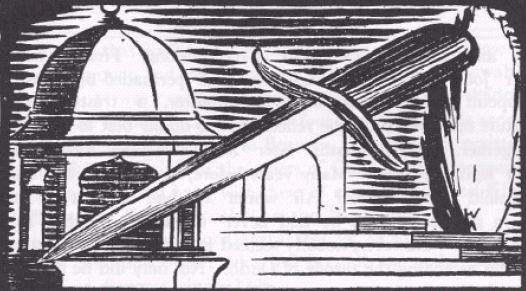

Portraits show Asaf-ud-Doulah as a squarely built man of portly mien, with protruding eyes and pendulous moustaches. His dress, of the finest white muslin, reached to his instep and was very full, bordered by rich metal braid. Long sleeves were caught at wrist and upper arm by bands of embroidery. His closely wound turban was overlaid with plaques of precious stones, surmounted by valuable aigrettes. About his waist wound a thick scarlet-and-gold cord into which was thrust a large jewelled dagger.

When the fame of the Court of Oudh was firmly established an English artist named William Hodges, who had been a member of Captain Cook’s expedition to the South Seas, visited India, where he secured the patronage of Warren Hastings. In company with another artist, John Zoffany, who was then coming to the end of his monetary resources in England, and who had obviously been stirred by the extravagant tales of wealth at the court of Oudh, Hodges set sail in 1783. The two artists landed at Calcutta, whence they made their way upcountry to Lucknow. Hodges did not make much headway but Zoffany quickly established a reputation for himself, and in 1784 he painted a portrait of the Nawab, inscribed: “John Zoffany painted this picture at Lucknow A.D. 1784 by order of His Highness the Nawab Vizier Asoph-ud-doulah, who gave it to his servant Francis Baladon Thomas.” Zoffany immortalised a favourite sport of the day in what is, perhaps, his best-known picture, ‘Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match’, painted in 1786.

In this picture appears a portrait of the Nawab and of other well-known contemporaries, both Indian and European. During Asaf-ud-Doulah’s reign seven British Residents successively assisted in the administration of his lands and revenue. In 1794 one Thomas Twining of the Civil Service accompanied the Commander-in-Chief of the Company’s army on a tour of inspection. On January 5, 1795, Twining wrote: “I dined to-day with Mr. Orr, an English merchant, and met a large party of English gentlemen, among whom was Dr. James Laird, brother of the head physician who accompanied Sir Robert Abercrombie from Calcutta. There were also Mr. Paul and Mr. and Mrs. Arnot. Mrs. Arnot enjoys the distinction of being the handsomest lady in India.”

Mr. Orr was a rich merchant who resided for many years in Lucknow, besides possessing a bungalow at Tanda near Fyzabad, where also were situated one of his several cotton cloth factories. Twining was agreeably impressed with Lucknow society for he wrote that “the style in which this remote colony lived was surprising, it far exceeding even the expense and luxuriousness of Calcutta. As it was the custom of these families to dine alternately with each other they had established a numerous band of musicians.”

Of the Nawab himself, Twining noted that “in polished and agreeable manners, in public magnificence, in private generosity, and also, it must be allowed, in wasteful profusion, Asafud- Doulah, Nawab of Oudh, might probably be compared with the most splendid sovereign of Europe.”

The Nawab had a great admiration for things European and things mechanical. In a building known as the Ina Khana he made a collection of objects which, so long as they were English, needed no other common denominator. Watches, clocks, scientific instruments, firearms, glass, and furniture were jumbled together in utter confusion.

Timepieces studded with jewels and exquisitely ornamented in coloured enamels lay cheek by jowl with the most tawdry imitations. Each had probably cost the Nawab an equal sum of money, and each had presumably caught his attention for a similar number of minutes. Above this quaint muddle of trumpery and jewels hung a myriad crystal prisms, reflecting the light diffused from a number of wall and table lamps set here and there with little thought of artistry.

In 1784 a famine came upon Lucknow. As a relief measure and to give employment to his people, Asaf-ud-Doulah caused architects throughout India to submit plans for a building to be known as the Great Imambara.

But the Nawab, although he built great palaces, laid out beautiful gardens and sank wells, had no eye for the squalor of his immediate surroundings. The city itself was a miserable place; the streets were narrow, dirty, and crowded with bazaars and very poor people. “It was evident,” writes one spectator, “that splendour was confined to the palace while misery pervaded the streets: the true image of despotism.”

In spite of this the Nawab was held in affection by his subjects until the day of his death and was laid to rest beneath the high vaulted ceiling of the Great Imambara, for which, rumour has it, over a million English pounds bought the ornate chandeliers and mirrors to complete the state’s bankruptcy.

As a result of extravagance and lack of supervision over petty court officials and taxcollectors, the court of Oudh found itself almost penniless at the death of Asaf-ud-Doulah in 1798.

Amjad Ali Shah

1842—1847

King Amjad Ali Shah Was the second son of his predecessor Muhammad Ali Shah. His elder brother Ashar Ali died young so that his son Mumtaz-ud-Doulah, formerly in direct succession, was thenceforward of no account.

It was already May when the old King died, but undeterred by the heat of the summer, Amjad Ali Shah gave full rein to excess and vice. All reforms attempted by his father were nullified. The country went from bad to worse. Almost the only good things he seems to have done were to erect the Iron Bridge over the Gumti, which had been lying by the wayside for more than thirty years, and to construct the road to Cawnpore which still follows the same route. His minister Amin-ud-Doulah built the great Aminabad bazar and serai on the Cawnpore Road now engulfed in the heart of Lucknow city.

The King also built his own mausoleum and the street of Hazrat Ganj, in which it now lies forgotten and deserted, given over to rats, cobwebs and decay.

Von Orlich visited Lucknow soon after Amjad Ali Shah’s accession and was granted audience by the King in the Farhat Bakhsh. General Nott was the new Resident and was assisted by Captain Shakespeare who had been one of the actors in the tumultuous scene at Muhammad Ali Shah’s accession.

The Resident presented Von Orlich to the King, who impressed the visitor as being tall, rather fat, benevolent-looking, but extremely ugly, having an enormous nose. On this occasion he wore a robe of green silk lavishly embroidered with gold and silver threads, which opened to disclose red silk pantaloons and gold embroidered shoes.

Upon his head he wore a high jewelled cap. Round his neck and upon his fingers flashed priceless jewels. Amjad Ali Shah is always depicted as wearing the most gorgeous robes and jewels. Not one costly chain but four hung round his neck, a magnificent osprey surmounted his crown, which blazed with jewels. In the palace a special table was reserved for a large assortment of head-dresses for it pleased the King to change these at frequent intervals.

At the end of an interview the chamberlain produced the golden embroidered garlands for which Lucknow is still justly famed. The royal ones were made of silver thread and incorporated the kingly arms of two swords, a tiara, a crown, and the famous fish emblem embossed in gold upon silver shields. These garlands the King with his own hand placed around the necks of his visitors before escorting them to the entrance of the palace. There he was wont to embrace them, shake them warmly by the hand and retire.

King Amjad Ali Shah cared nothing for manly sports. Instead, he passed a great deal of his time in his harem where dwelt a very remarkable woman, his chief wife, daughter of Hasinud- Din, Khan of Kalpi. Hers were not the only attractions which drew the King so often to the women’s quarters of the palace. He had nearly two hundred concubines. His eldest son thus had the worst possible upbringing for one of his inherited tendencies.

This King cared nothing for affairs of state and took no interest in the government of his country in spite of repeated representations from the British Resident that if he did not mend his ways of his own accord, steps would be taken by the Governor-General to see that he was made to do so.

In 1845 Sir Henry Lawrence paid a tribute to these kings. He said: “The Oudh rulers have been no worse than monarchs so situated usually are; indeed, they have been better than might have been expected. Weak, vicious, and dissolute they were, but they have seldom been cruel, and have never been false. In the storms of the last half century, Oudh is the one single native state that has invariably been true to the British Government: that has neither intrigued against us nor seemed to desire our injury.”

The verdict of so stern a moralist should be remembered by those who are inclined to think of all the Kings of Oudh alike as monsters of treachery and misrule.

The Badshah Bagh

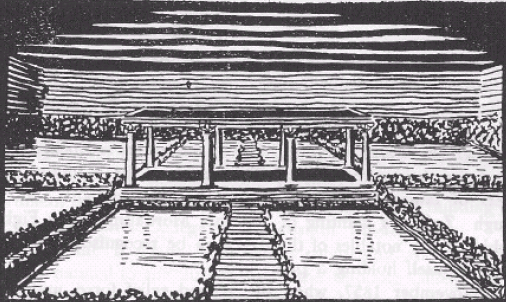

King Nasir-Ud-Din Haider, about a hundred years ago, built himself a high-walled garden which he called the Badshah Bagh. In the centre of pleasant walks was an open hall supported by fine carved pillars, where were held the festive gatherings of the period. Between the formal walks, gaily-hued flowers bordered shallow marble lakes filled with sweet-scented rose water, in which the favourites of the harem were wont to disport themselves.

The King is reputed to have included European beauties in his harem. For them he built the Walaiti Bagh. Within the Badshah Bagh he caused a square house washed in red ochre to be erected for their convenience. Thither also the nobility and leaders of fashion would repair to witness cock-fights, famous through Zoffany’s painting of “Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Fight” in which many notables of the day may be recognised, including Zoffany himself holding a paint brush.

In November 1857, when the second relief force under Sir Colin Campbell had advanced to within a few hundred yards of their objective, the enemy made one last attempt to prevent the British from crossing the river, raking the troops with a heavy fire from the Kaisar Bagh in front and from the Badshah Bagh behind. A few months later, in March 1858, the British erected a battery at the south-west corner near the river to bombard the Kaisar Bagh whose inhabitants still clung to a forlorn hope.

Soon afterwards the Badshah Bagh became the property of the Maharajah of Kapurthala, In the garden stands a stone cross beneath which lie the remains of the eldest son of one of die Maharajahs. He became a Christian and thereby forfeited the right both to succeed to the throne and to be gathered unto his fathers when death befell him.

On May 1, 1864, a high school was opened in the Aminabad Palace, attended by over two hundred boys. The Taluqdars of Oudh guaranteed to contribute Rs. 25,000 annually towards its upkeep provided the Government did the same. Two years later it was raised to the status of a College, known as the Canning College. In 1867 it was affiliated to the Calcutta University for the Bachelor of Arts Degree and for Law in 1870. Later it was affiliated to the Allahabad University.

At one period the College was housed in a building within the Kaisar Bagh, once the seat of Government and now a museum housing stone carvings, belonging to the Government of the United Provinces. At present the building is used by the Marris College of Hindustani Music.

In 1905 the Badshah Bagh estate comprising about ninety acres was handed to the authorities of the Canning College. Sir John Prescott Hewett, Lieutenant-Governor of the Province, laid the foundation-stone of the new College in 1909, and performed the opening ceremony in 1911 Little remains of the original buildings. The new ones are fine and imposing surrounded by the traditional restful green lawns and tennis courts.

The Begum Kothi

The Begum Kothi Must Not be confused with the house of the same name within the Residency enclosure. It stands on the left hand side of Hazrat Ganj, coming from Cantonments. Until 1932 the house including a large group of buildings huddled round the central one was used as the General Post Office. The Begum Kothi was built by King Amjad Ali Shah in 1844 as a palace for his Queen, Malka Ahad Begum. One authority attributes it to Sa’adat Ali Khan about forty years earlier. Possibly Amjad Ali Shah reconstructed his palace upon the site of a former one.

The building was not conspicuous during the Mutiny until March 1858, when two batteries, including the naval guns of H.M.S. Shannon, bombarded it continuously for twentyfour hours and made two breaches in the wall near where Abbott Road now runs. The 93rd Highlanders were ordered to storm the Begum Kothi at these two points, supported by the 4th Punjab Rifles and five hundred of Jung Bahadur’s Gurkhas.

When the bombardment ceased they charged forward, leaping over a ten-foot ditch and a parapet, and took their opponents completely by surprise, so rapid was their advance. The Grenadier Company led by Captain Middleton and Lieutenant Wood, scrambled through the right hand breach, while the Light Company, headed by Captain Clarke and Lieutenant Macpherson, tackled that on the left. They all dashed headlong into the narrow alleys and courts and buildings in which some five thousand of the enemy were said to be ensconced.

They followed to the letter their orders to “Keep well together and use the bayonet; give them the Sikandar Bagh over again.” Although the garrison of the Begum Kothi numbered about five thousand, they made no attempt to meet the British face to face in the open. The fighting was severe for large nambers found their retreat cut off by the rush of the attackers past the rooms, archways and passages where they were concealed. Being unable to escape, they fought desperately. From every loophole, door and window, and from every hidden corner in the dark interior came a deadly fire. Many barriers were forced. Small parties headed by officers took possession of one enclosure after another.

They pitched bags of gunpowder fixed with slow matches into the crowded rooms and bayoneted the rebels in every nook and corner. For about two hours the blind and bloody fight raged from court to court, from room to room. So rapid was the progress of the troops through the buildings that the Begum herself narrowly escaped capture. About eighty of her female attendants were taken prisoners and proved an embarrassing encumbrance.

Captain Charles William McDonald of the 93rd Highlanders was wounded by a shell splinter in the right arm at the very beginning of the charge, but he refused to heed it until he was again wounded in the throat, this time mortally. His remains are buried near Dilkusha under an inscription erected by his relations : “In memory of his simple virtues as a Christian and his noble conduct as a soldier.”

By the evening the attackers were in possession, at the price of many casualties. The foe had suffered even more heavily.

When the attack was announced by signal gun, the famous Major Hodson of the Guides and Hodson’s Horse was at the camp at Headquarters. He at once leapt upon his horse and galloped to the spot. There he plunged into the thick of the fight, being mortally wounded as he attempted to climb a staircase.

He was carried to Banks House in great pain, there to die the next morning saying, “I trust I have done my duty.” He lies buried in La Martinière park near the College under one of the finest epitaphs that have ever been written: “Here lieth all that could die of William Stephen Raikes Hodson.” One of the few that can be compared with it is the inscription on the grave of Sir Henry Lawrence in the Residency cemetery—”Here lies Henry Lawrence, who tried to do his duty.”

Bibiapur Kothi

About A Mile To The South-East of Dilkusha lies the Bibiapur Kothi, shielded from view by the Government Dairy Farm. The two-storeyed building is solid and stands on high ground to command a fine view of the country. Originally surrounded by a big park, its origin is shrouded in obscurity, but it was built under the direction of General Claude Martin for Nawab Asaf-ud-Doulah who stayed there from time to time, using it as a hunting box. Its chief use was as a guest house for the incoming British Resident when a change of officials took place.

Incidentally it was from here that Sir John Shore (afterwards Lord Teignmouth) had issued the deposition orders of the usurper Wazir Ali, alleged son of Nawab Asaf-ud-Doulah, in 1798 ; at the same time summoning Sa’adat Ali Khan from Benares and welcoming him with an impressive durbar at Bibiapur before taking him in procession to the city where he was proclaimed Nawab. Years later, in 1856, Colonel Outram received instructions from Lord Dalhousie to proceed to Lucknow from Calcutta to acquaint the King of Oudh with the terms of a treaty. On nearing Lucknow the newly-appointed Resident was escorted by a detachment of irregular cavalry.

The road was lined all the way by crowds anxious to see the man to whom the destinies of their state had been committed. When approaching the Char Bagh, a salute was fired by the Oudh Artillery announcing that the Resident had nearly completed his journey. On these occasions it was the etiquette that the Resident should not enter the city but stay as guest at some garden palace belonging to the King. On his arrival another royal salute from His Majesty’s guns proclaimed the presence of the Resident to the public. When he had resided outside the city for the time demanded by etiquette, the reigning King advanced to meet him with all the pomp and ceremony at his command.

An eye-witness of the occasion when Outram arrived as Resident, in December 1856, describes the scene of splendour. Long before sunrise thousands upon thousands crowded the roads and clambered upon the roof of every-building whence they could catch a glimpse of the procession.

A guard of honour consisting of the flank companies of the 19th, 34th and the 2nd Oudh regiments, their colours flying, were drawn up in the park to do honour to Colonel Outram and to salute the heir-apparent.

The troops were officered by Europeans under the command of Major Troup. Accompanying them was the band of the 19th Regiment. “Let the reader imagine a procession of more than three hundred elephants and camels, caparisoned and decorated with all that “barbaric pomp’ could lavish and Asiatic splendour shower down, with all the princes and nobles of the kingdom blazing with jewels, sparkling with gems, gorgeous in apparel, with footmen and horsemen in splendid liveries, swarming on all sides, pennons and banners dancing in the sun’s rays, and a perfect forest of gold and silver sticks, spears and other insignia of imperial and royal state.”

Slowly and with stately tread the procession approached the newly-appointed official. With equal pomp and gravity the Resident’s coach advanced to meet it. As the King and his new adviser met, the guns again thundered forth a royal salute. The Englishman took his place beside the King, whereupon the whole procession retraced its steps to the city. The way was a sea of heads, their owners decked in gala attire. The heir-apparent presented the newcomer with a bag of Rs. 1,200 for distribution amongst the crowds of beggars and vagrants who, as ever, shouted baksheesh, baksheesh !

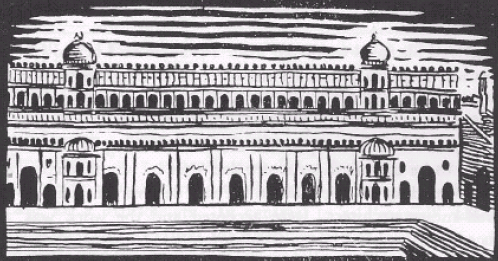

Bara Imambara

As in 2021

The Times of India, Oct 9, 2011

The entrance of Bara Imambara is encroached by shops and eating joints. Inside, many families live, some in underground cells in the mosque. An ASI report says out of 56 protected monuments, 24 are encroached upon, some by residents, others by shops, trusts and government agencies. O P Pathak, additional district magistrate, Lucknow, says with an air of resignation, “Efforts were made for over four decades to get these monuments vacated, but the inhabitants move court and the process is halted.” But Mohammed Jabir, a chikankari worker, says, “My forefathers have been living here. Leaving this place will take away our shelter and our jobs.” – Shailvee Sharda

A backgrounder: a food for work project

April 7, 2024: The Times of India

We decided to visit the Bada Imambara in the two hours before the flight. This is an enormous prayer hall from the 1780s, sponsored by the then Nawab of Awadh, Asaf-ud-daula, in response to a terrible drought and resulting famine. It was a food-for-work program — anyone who came for work on the building project got some basic provisions.

There is a famous maze inside the imambara called the Bhulbhulaiya. The guide we took to avoid getting lost told an interesting story. Apparently, the local upper classes were also starving — not surprising given that they too lived off the land. The nawab, he said, knew that they were too proud to show up for work with the everyday labourers. So, instead, he paid them to come hidden in the dark of the night to demolish a part of the day’s work.

I am not sure I entirely believe it, but it’s a great story. Two interesting points come out of it. First, the nawab wanted people to work for their food. I am no expert, but I don’t think of that as an Indian tradition. Sita crossed the Lakshman Rekha to honour a beggar (Ravana in disguise) even though she was expressly forbidden to do so. She didn’t think of what work she was going to ask him to do in return. Bhikkhus and fakirs have a very specific role in Indian religious culture, and both Hindu and Muslim families would think twice before turning either away, and would certainly never ask them to do something in return. On the other hand, the Rohilla chieftain Hafiz Rahmat Khan was using famine-hit labour for public construction, including for the famous Pilibhit mosque, even before 1780. Where did he get the idea?

Second, the dignity of the welfare recipients was important to the nawab. Whether or not I think this is the right priority, he cared about the fact that ashraf Mussalmans would rather die than work shoulder-to-shoulder with their own servants, just as we children knew not to dig too deep when one of our once-prosperous relatives showed up without the gold bangle she always wore, and claimed it was lost.

Both these choices — should there be a work requirement and how to treat the beneficiaries — would become important issues for the British, who, exactly around 1780, assumed the over-lordship of large parts of northern India and, therefore, the responsibility for managing the periodic droughts and consequent famines that afflicted the area. Being a private company mostly dedicated to making money, this troubled them a lot. Land revenue was an important part of its earnings, and collections tended to fall in drought years. They were, therefore, not exactly keen to spend more money to help the starving.

But it was not possible to do nothing. During the 1783 famine, the fledgling East India Company administration discovered that many people left their homes in search of work and food and never came back. Others died. Large areas were depopulated. With no people to work the land, productivity and land revenue crashed.

Moreover, it is hard to get people to pay taxes to a state that seems indifferent to their well-being, and in those early days, the Company knew that it was being compared with the regimes it displaced (or was trying to displace), like Awadh. Finally, and perhaps equally importantly, on the ground, the Company was represented by people, British men and women, often quite young, for whom the starving faces and the piling dead bodies were a daily reality. They could not but want to do something. Fanny Eden, sister to Lord Auckland, the-then Governor-General of India, writing during the brutal 1838 famine, put it bluntly: “But it is no affection to say that when we sit down to dinner with the band playing and all the pomp and circumstances of life about us, which is just as much kept up in a tent as anywhere else, my very soul sickens at the cries of the starving children outside which never seem to cease.”

I know all this only because one of my dearest friends from my JNU years, Sanjay Sharma, is the author of the seminal book, ‘Famine, Philanthropy and the Colonial State: North India in the Early Nineteenth Century’. Sanjay observes that the bottom-up pressure to relieve the misery caused by the famines ran up against the growing influence of laissez-faire thinking in Britain at the time. Indeed, many of the ameliorative efforts by the local (British) administrators got squashed by their higher-ups. This, of course, was partly just being cheap. But there was a strong ideological element in it too, in keeping with the contemporary emphasis on “scientific economic basis” for charity, in contrast with Indian traditions, which placed a value on the giving itself. These were frequently described by British observers as irrational or hypocritical, based on piety and the desire to earn credit in heaven. ‘Rational charity’, on the other hand, was all about avoiding waste: “Overly generous” policies were frowned upon because they might encourage people to stop working and live off public munificence (they also cost the Company more).

The debate on how to ensure that charity was also ‘good economics’ went on for years. In the meanwhile, there were famines when little was done, and many died. It was only during the awful 1838 famine that Ms. Eden was writing about, that a clear policy of providing public employment to the needy, much like in Lucknow and Pilibhit, emerged. However, Fanny’s brother, the Governor-General, made sure that these jobs would be paid so little that only those who had no choice would take them. And to make it more acceptable to the devotees of economic rationality, the plan was to put the labour to good use. To build irrigation canals, which would raise productivity and prevent famines, and roads to move grains to where there was scarcity. In fact, many got built.

This only covered those who were able to work. The rest, like women with young children or the handicapped, were left to their fate. It was only after 1861 that the government started building poor-houses where such people could get some food, after many intense debates about just how little dal-roti could suffice.

None of this prevented the recurrence of murderous famines. Bad weather and blind ideology continued to take their toll. Estimates suggest that 8.2 million people died just in the 1876-78 famine. But for better or worse, these ideas continue to guide our approach to social transfers.

MGNREGA, of course, is modelled exactly on the public works of the earlier periods, though Lord Auckland would have surely thought it was too generous. Perhaps as a result, it works. Research by Clement Imbert and John Papp shows that it reduces rural poverty.

At the same time, our governments are still all too concerned with ensuring that only the truly desperate, prepared to navigate the bureaucratic mazes and not be discouraged by the many engineered dead-ends, get benefits. Getting a widow’s pension in Delhi, a study by the World Bank’s Sarika Gupta tells us, requires two visits, on average, to the local MLA among the many tedious and/or humiliating steps. As a result, many of the eligible just give up. Our recent work in Tamil Nadu finds something similar. Maybe we should consider relaxing a bit about keeping the undeserving out, so as not to exclude those in real need. And perhaps even try to be respectful of the beneficiary’s humanity: I imagine the nawab sanctioning some mithai (shahi tukra?) for his workers on the rare parab days. I suspect Lord Auckland wouldn’t.

I imagine a household in famine times, relieved that they had resisted the Company’s push towards cash crops and monocultures and planted some hardy millets that luckily survived the drought, making a delicious khichdi with whatever else they had, scraps of vegetables, some dal and peanuts for protein.

This is part of a monthly column by Nobel-winning economist Abhijit Banerjee illustrated by Cheyenne Olivier.

The Chutter Munzil

Probably Everybody knows that the United Service Club, otherwise the Greater Chutter Munzil, was once a palace belonging to the Kings of Oudh, but how many realise that formerly there were two storeys below the present three ?

Under the existing river terrace was the “ground floor” and below that again were the tykhanas, cooled by the waters of the Gumti which lapped against the outer walls. Considering their size, surprisingly little is known about the Chutter Munzil Palaces. The name comes from the gilt “chhuttars” or umbrellas at the top of the two main buildings. Their conception is attributed to no less than three Nawabs, Sa’adat Ali Khan, Ghazi-ud-Din, and his son Nasir-ud-Din. Whoever was responsible, present-day experts characterise the building as “a flagrant example of the hybrid style” of Muhammadan architecture allied to debased French or Italian art.

The buildings were intended for the Kings’ wives. Originally the palace area extended from the Baillie Gate to some distance beyond the present club entrance, the whole collection being enclosed by a high wall of considerable strength.

The present residential club quarters were known as the Farhat Bakhsh Palace, the property of General Claude Martin who sold it for Rs. 50,000 to King Sa’adat Ali Khan. Miss Eden who visited Lucknow before the Mutiny went into ecstasies over the Chutter Palaces.

“Such a place,” she wrote home to England, “is the only residence I have coveted in India. Don’t you remember reading in the Arabian Nights, Zobeide bets her Garden of Delight against the Caleph’s Palace of Pictures ? I’m sure this was the Garden of Delight. “There are four small places in it fitted up in the Eastern way with velvet, gold and marble, with arabesque ceilings, orange trees and roses in all directions and with numerous wild paroquets of bright colours flitting about. And in one place there was an immense hammam or Turkish bath of white marble, the arches intersecting each other in all directions and the marble inlaid with cornelian and bloodstone, and in every corner of the palace there were little fountains ; even during the hot winds, they say, it is cool from the quantity of water in the fountains playing ; and in the verandah there were fifty trays of fruits and flowers laid out for us.”

Tradition hints at a large tank lying between the Greater and Lesser Chutter, although there is no evidence to prove either that or the supposition that a subterranean passage leads from the Greater Chutter under the river to the far bank of the Gumti.

Other buildings embraced in the term Chutter Munzil are the Darshan-Bilas (Pleasure to the Sight) and the Gulistan-i-Eram (Heavenly Garden), now the Public Works Department offices. Either in the Gulistan-i-Eram or in the Farhat Bakhsh occurred the death of Nasir-ud- Din Haider, the second King of Oudh.

On the night of July 7, 1837 King Nasir-ud-Din accepted from a woman a glass of sherbet, which is said to have contained powdered glass. He died there and then. For nearly twenty years after that the Chutter buildings again echoed to the soft laughter of women of the royal harem, until the first mutterings of the Mutiny froze the smile upon their lips. By then the out-buildings of the Palace extended almost to the Monkey Bridge, and a perfect web of narrow passages and courtyards had sprung up on the space now presided over by the statue of Her Majesty Queen Victoria.

The Chutter Munzil palaces were important strongholds of the rebels. Their capture had to be effected by the relieving force on their difficult path to the Residency. Late in September 1857, Havelock’s column moved towards the Residency to receive a sharp check at the Char Bagh bridge which lay over a canal now forgotten. The resistance was soon overcome, however, with the aid of Maude’s battery and a charge by the Fusiliers.

Fighting every foot of the way, the relief column halted beneath the comparative shelter of the Chutter Munzil. Next day they gained the Residency. On November 16, the beleaguered garrison knew that the second relieving force under Sir Colin Campbell was advancing by way of the Sikandar Bagh.

The besieged troops were drawn up in the courtyard of the Chutter Munzil which was reoccupied by the rebels. When the advance sounded at half past three that afternoon, General Havelock says in his report that it was “impossible to describe the enthusiasm with which this signal was received by the troops. Pent up in inaction for upwards of six weeks and subjected to constant attacks, they felt that the hour of retribution and glorious exertion had returned. Their cheers echoed through the courts of the palace, responsive to the bugle sound, and on they rushed to assured victory.

The enemy could nowhere withstand them. In a few minutes the whole of the buildings were in our possession.” On November 19 when Sir Colin Campbell decided finally to evacuate the Residency, the way to freedom lay through the Chatter Palace area ; from there to the Moti Mahal the route was still subject to musketry fire. An old legend whispers of an unseen servant who carries a lantern from room to room of the upper storey ; rooms which in he broad light of day are found to be non-existent.

Dilkusha Palace

The Palace Of Dilkusha —“Heart’s Delight”—was built by Nawab Sa’adat Ali Khan (1798-1814). It was erected as a hunting box in the centre of a large park stocked with all manner of game that disported among the great trees. Near by lay a large shallow lake upon which the Nawabs, especially Nasir-ud-Din Haider, would conduct bird shoots. At first shooting was the primary object, with comfort a bad second.

As generation succeeded generation, however, the ratios were reversed. Everything was sacrificed to comfort and the birds were so tamed for weeks beforehand that a shoot amounted almost to wholesale slaughter. In 1814 Lord Hastings, the Governor-General, visited Lucknow and shot in the Dilkusha park but sport was moderate. At that time it had a circumference of about three miles. It was thickly wooded with a dense tropical undergrowth.

In the troubles of 1857 Havclock spent some time discussing routes by which to approach the Residency, one of which was by way of Dilkusha, La Martinière, and the Sikandar Bagh, but ultimately he decided to take a more direct route. On November 14, Sir Colin Campbell, with the second relief force, advanced from the Alam Bagh by way of Dilkusha. The rebels had not expected him to go by this route and were taken by surprise.

However, they put up a stiff resistance. After a sharp interchange of hostilities the British force made a breach in the park wall and poured in, driving the enemy pell-mell before them. Two batteries were brought up and placed in position upon a commanding slope to the north-west of Dilkusha Palace and supported the infantry advance.

On November 16, the force pressed hard on their adversary’s heels, leaving the Eighth Foot to garrison Dilkusha.

When the relief of the Residency was at last accomplished the main body of the survivors evacuated the position by way of the Sikandar Bagh, and thence to Dilkusha whither the troops, last to leave the historic site, marched by a more direct route through the city. On November 20, General Havelock fell ill and was taken to Dilkusha. There Sir Colin Campbell visited him on the evening of the 23rd, and wrote later: “I had a most affecting interview with him.

His tenderness was that of a brother. He told me he was dying and spoke from the fulness of his honest heart of the feelings which he bore towards me, and of the satisfaction with which he looked back to our past intercourse and service together, which had never been on a single occasion marred by a disagreement of any kind, nor embittered by an angry word. How truly I mourned his loss is known to God and my own heart.” The next morning the great soldier breathed his last. Havelock died fearlessly, saying only a few minutes before the end, “I have, for forty years, so ruled my life that when death came I might face it without fear.” He was buried in a soldier’s modest grave at the Alam Bagh the next day.

Several others lie buried beneath die shadow of the crumbling walls. Among them are Lieutenant Paul of the 4th Punjab Rifles, who was killed at the Sikandar Bagh, Captain Macdonald of the 93rd Highlanders who, “although he had been a Captain for some years, was still almost a boy”, and Lieutenant Charles Dashwood, affectionately known to the whole garrison as Charlie Dashwood.

He had been through the entire siege and had both his legs shot off while sketching in the gardens of the Residency. An operation was performed, but his health was too weak to stand it, and he died from exhaustion when freedom was within sight. When the troubled land was once more peaceful, Dilkusha was restored and became the residence of the General Commanding the Oudh Division, until it was declared to be unsafe. It was partially demolished and lies almost derelict now. From the top of the tower there is a fine panorama of Lucknow and its surroundings, peaceful and prosperous at last.