Polygamy in India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

How widespread is polygamy?

2019-20

Rema Nagarajan , July 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan , July 28, 2022: The Times of India

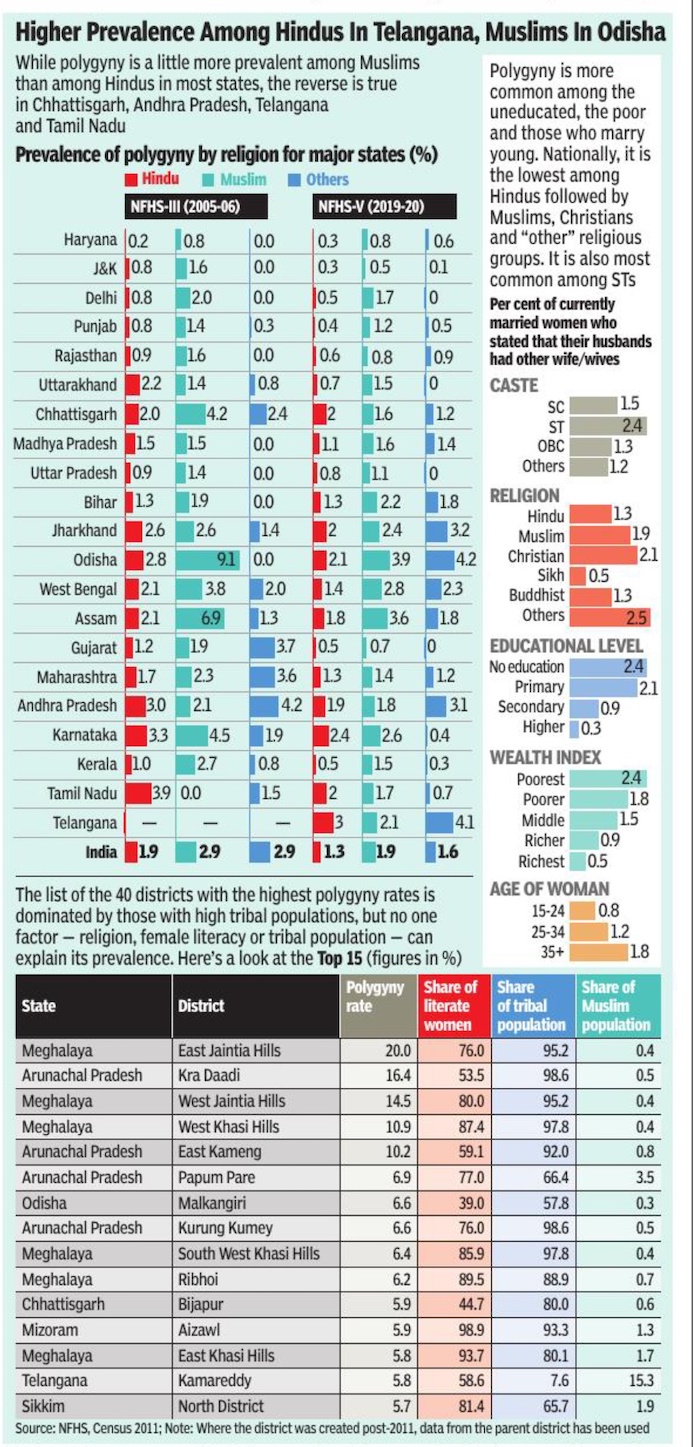

Polygyny or the practice of having more than one wife is legal in India only for Muslims, but National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data shows it is almost as prevalent in other communities, though on the decline in all. The latest NFHS data from 2019-20 shows the prevalence of polygyny was 1. 9% among Muslims, 1. 3% among Hindus and 1. 6% among other religious groups.

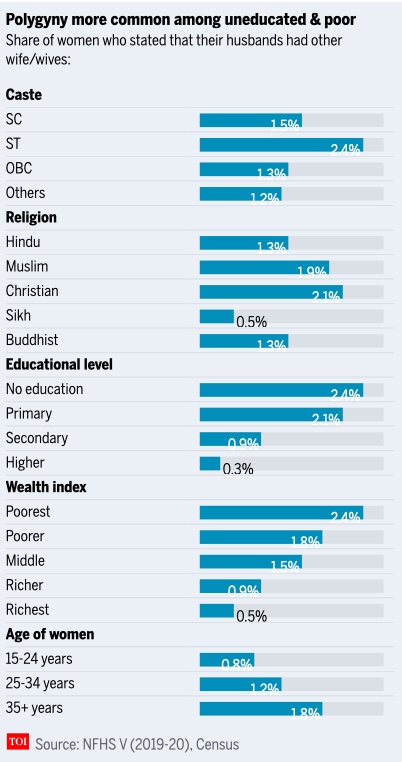

This was revealed in an analysis of data from the three NFHS rounds of 2005-06, 2015-16 and 2019-20 done by faculty from the International Institute of Population Studies in Mumbai, which also conducts the NFHS. “Overall, polygynous marriage was found to be higher among poor, uneducated, rural and older women. It indicated that socio-economic factors also played a role in this form of marriage in addition to region and religion,” stated the authors of the recently published research brief, adding that the prevalence of polygyny in India was very low and fading away.

The prevalence of polygyny here is the percentage of married women in the 15-49 age group who indicate that their partner has more than one wife. In India, polygynous marriages have decreased from 1. 9% in 2005-06 to 1. 4% in 2019-20. The northeastern states with high tribal populations have the highest proportion of women reporting polygyny, ranging from 6. 1% in Meghalaya to 2% in Tripura. The southern states and those in the east like Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal have higher prevalence of polygyny than North India.

Among caste groups, polygyny is most prevalent among scheduled tribes, at 2. 4%, a decline from 3. 1% in 2005-06, followed by scheduled castes (1. 5% in 2019-20 as against 2. 2% in 2005-06). Thus, states with a higher proportion of tribal population seem to have the highest prevalence of polygyny.

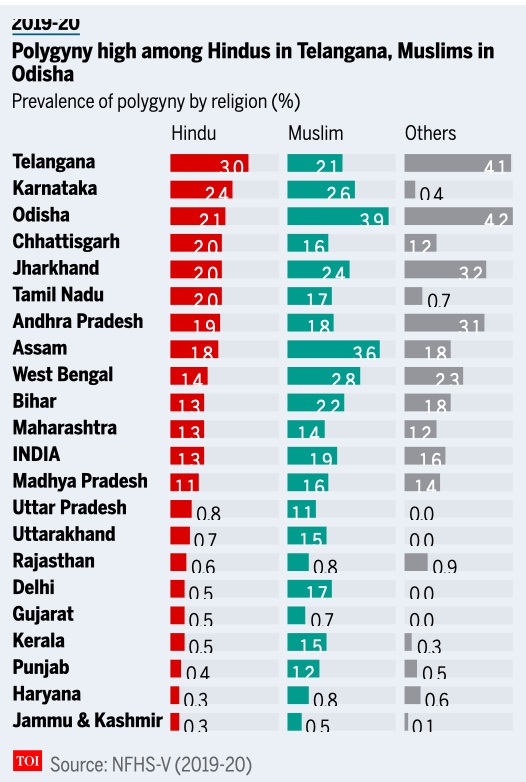

The broad patterns, however, have exceptions. For instance, while there is a higher prevalence of polygyny among Muslims than among Hindus in most states, the opposite is true in states like Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Tamil Nadu.

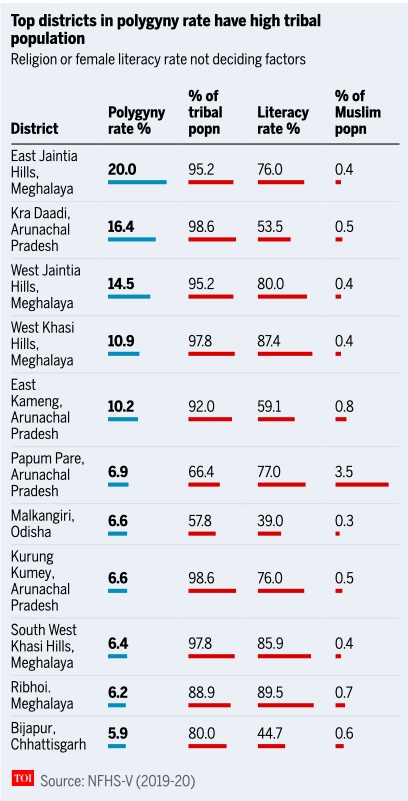

TOI looked at the 40 districts identified by the study as those with the highest prevalence of polygamous marriages. Analysing this list with data from the Census on female literacy as well as the share of religious groups and tribals in the total population showed that no single background characteristic could be attributed as the reason for higher prevalence of polygyny, though predominantly tribal districts seem to have high prevalence ranging from a high of 20% in the East Jaintia Hills district in Meghalaya to Anuppur in Madhya Pradesh at the 40th place with 3. 9%.

Among religious groups, polygyny was most common among “others” (2. 5%), followed by Christians (2. 1%), Muslims (1. 9%) and Hindus (1. 3%). The high prevalence among Christians could be because of northeastern states, where the practice is more common.

The survey also found polygynous marriages were more prevalent among the poorest women and women with no formal education than among those who had higher educational qualifications. However, the higher prevalence of polygyny in districts in Tamil Nadu and the Northeast with very high literacy rates shows that it is not just about literacy. In all rounds of NFHS, polygynous marriages were higher among older women aged 35 years and above, partly an indication of the practice being on the decline.

2005-20

Rema Nagarajan, July 28, 2022: The Times of India

May 11, 2023: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 28, 2022: The Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, July 28, 2022: The Times of India

How polygyny is declining, even among Muslims

Polygynous marriages are not confined to a fixed religion and have declined across all. The national average is down from 1.9% in 2005-06 to 1.4% in 2019-20, according to survey findings

Polygyny or the practice of having more than one wife is legal in India only for Muslims, but National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data shows it is almost as prevalent in other communities, though on the decline in all. The latest NFHS data from 2019-20 shows the prevalence of polygyny was 1.9% among Muslims, 1.3% among Hindus and 1.6% among other religious groups.

This was revealed in an analysis of data from the three NFHS rounds of 2005-06, 2015-16 and 2019-20 done by faculty from the International Institute of Population Studies in Mumbai, which also conducts the NFHS. “Overall, polygynous marriage was found to be higher among poor, uneducated, rural and older women. It indicated that socio-economic factors also played a role in this form of marriage in addition to region and religion,” stated the authors of the recently published research brief, adding that the prevalence of polygyny in India was very low and fading away.

The prevalence of polygyny here is the percentage of married women in the 15-49 age group who indicate that their partner has more than one wife. In India, polygynous marriages have decreased from 1.9% in 2005-06 to 1.4% in 2019-20.

The northeastern states with high tribal populations have the highest proportion of women reporting polygyny, ranging from 6.1% in Meghalaya to 2% in Tripura. The southern states and those in the east like Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal have higher prevalence of polygyny than North India.

Among caste groups, polygyny is most prevalent among scheduled tribes, at 2.4%, a decline from 3.1% in 2005-06, followed by scheduled castes (1.5% in 2019-20 as against 2.2% in 2005-06). Thus, states with a higher proportion of tribal population seem to have the highest prevalence of polygyny.

The broad patterns, however, have exceptions. For instance, while there is a higher prevalence of polygyny among Muslims than among Hindus in most states, the opposite is true in states like Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Tamil Nadu.

TOI looked at the 40 districts identified by the study as those with the highest prevalence of polygamous marriages. Analysing this list with data from the Census on female literacy as well as the share of religious groups and tribals in the total population showed that no single background characteristic could be attributed as the reason for higher prevalence of polygyny, though predominantly tribal districts seem to have high prevalence ranging from a high of 20% in the East Jaintia Hills district in Meghalaya to Anuppur in Madhya Pradesh at the 40th place with 3. 9%.

Among religious groups, polygyny was most common among “others” (2.5%), followed by Christians (2.1%), Muslims (1.9%) and Hindus (1.3%).

The high prevalence among Christians could be because of northeastern states, where the practice is more common.

The survey also found polygynous marriages were more prevalent among the poorest women and women with no formal education than among those who had higher educational qualifications.

However, the higher prevalence of polygyny in districts in Tamil Nadu and the Northeast with very high literacy rates shows that it is not just about literacy. In all rounds of NFHS, polygynous marriages were higher among older women aged 35 years and above, partly an indication of the practice being on the decline.

Is polygamy common in Assam?

May 10, 2023: The Times of India

The Assam government has decided to form an expert committee to study whether the state legislature has the authority to ban polygamy. The committee will scrutinise the provisions of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Act, 1937, along with Article 25 of the Constitution of India, in relation to the directive principle of state policy for a Uniform Civil Code (UCC).

The committee will engage in extensive discussions with all stakeholders, including legal experts, to arrive at a well-informed decision, the state government said on May 9.

The committee is expected to submit its recommendations within six months. Besides the legal aspect, it will also examine the religious as well as the personal aspect.

Polygamy is generally prohibited in all religious communities in India except Muslims. Practising polygamy is an offence punishable under Sections 494 and 495 of the Indian Penal Code except for the Muslim community wherein Section 2 of the Shariat Act governs the law pertaining to marriage, which allows polygamy.

What did the chief minister say?

Assam chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma said the ban was not directed against any particular community but against all those practising polygamy and “we will do this through consensus and not by force or aggression”.

“We are not going towards UCC for which a national consensus is required; the Centre will take the initiative on that...We are announcing our intention to ban polygamy in the state as one component of the UCC,” he said.

“We want to stop a man, whether Hindu or Muslim, from marrying several times...We want to ban polygamy and declare it unconstitutional and illegal through legislative action,” he said. “The expert committee will decide whether the Assam assembly is competent to do it, whether the President’s assent is required and also take the views of the various sections of the society.”

Is polygamy common in Assam?

Polygamy is common in the three districts of Barak Valley and in the central Assam areas of Hojai and Jamunamukh. The rate of polygamy among the educated, however, is very low and it is practically non-existent among the indigenous Muslim population, the chief minister said.

During the crackdown against child marriage in the state, it was found that many elderly men got married multiple times and their wives were mostly young girls belonging to the poorer section of the society, he said. “We will further intensify the operation against the perpetrators of child marriage along with the ban on polygamy,” he said.

Sarma pointed out that polygamy is practised in some tribal communities of the state too, though now it may not be as a community but on an individual basis. There are many cases where men have a first wife but as the law prohibits polygamy, they live with other women without marrying, which is worse, Sarma said. “De facto polygamy exists and the committee will also suggest ways to ban both formal and informal polygamy,” he added.

Why it isn’t about Muslims alone

May 10, 2023: The Times of India

Polygyny or the practice of having more than one wife is legal in India only for Muslims, but National Family Health Survey (NFHS) data shows it is almost as prevalent in other communities, though on the decline in all. The latest data from 2019-20 shows the prevalence of polygyny was 1.9% among Muslims, 1.3% among Hindus and 1.6% among other groups.

This was revealed in an analysis of data from the three NFHS rounds of 2005-06, 2015-16 and 2019-20 done by faculty from the International Institute of Population Studies in Mumbai, which also conducts the NFHS.

The northeastern states with high tribal populations have the highest proportion of women reporting polygyny, ranging from 2% in Tripura to 6.1% in Meghalaya. The southern states and those in the east like Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal have higher prevalence of polygyny than North India.

Among caste groups, polygyny is most prevalent among Scheduled Tribes, at 2.4%, a decline from 3.1% in 2005-06, followed by Scheduled Castes (1.5% in 2019-20 as against 2.2% in 2005-06). Thus, states with a higher proportion of tribal population seem to have the highest prevalence of polygyny.

The legal position

A: What do previous judgments say?

May 10, 2023: The Times of India

The Assam government stated that Section 2 of the Shariat Act was the subject matter of a challenge before the Supreme Court. In the Shayara Bano vs Union of India case (2017), the court declared the practice of triple talaq unconstitutional as it was discriminatory against Muslim women. Consequently, it struck down Section 2 to the extent it applies to triple talaq.

It is to be noted that in the Shayara Bano case, the issue of polygamy was also raised. The apex court observed: “Other questions raised in the connected writ petitions such as polygamy and halala would be dealt with separately. The determination of the present controversy may, however, coincidentally render an answer even to the connected issues.” However, the court did not render any findings with regard to polygamy and ruled only on the aspect of triple talaq. The issue of polygamy and its legality has constantly engaged the courts. In the Javed vs State of Haryana case (2003), the issue pertained to the disqualification of persons having more than two living children from contesting polls for the post of sarpanch. One of the arguments raised against such a disqualification criteria was that the Muslim personal law allowed polygamy and the same was obviously for procreating children. Therefore, any such restriction would be violative of Article 25 of the Constitution. Negating such contention, the Supreme Court held that although Muslim law permits polygamy, nowhere does it mandate or dictate it as a duty to perform four marriages. Marrying less than four women or abstaining from procreating a child from each and every wife in case of permitted bigamy or polygamy would not be irreligious or offensive to the dictates of the religion. Further, protection under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution is with respect to religious practice which forms an essential and integral part of the religion. A practice may be a religious practice but not an essential and integral part of the practice of that religion. The latter is not protected by Article 25, it added. In the Sarla Mudgal vs Union of India case (1995), the Supreme Court held that polygamy is injurious to “public morals” and even though some religions may make it obligatory or desirable for its followers, the same can be superseded by the state just as it can prohibit human sacrifice or the practice of sati in the interest of public order. Personal law operates under the authority of legislation and not under religion and, therefore, personal law can always be superseded or supplemented by legislation, the court added.

In the State of Bombay vs Narasu Appa Mali case (1952), it was held that a distinction must be drawn between religious faith and belief and religious practices. What the state protects is religious faith and belief. If religious practices run counter to public order, morality or health or a policy of social welfare upon which the state has embarked, then the religious practices must give way before the good of the people of the state as a whole.

Further, if the legislature in its wisdom has come to the conclusion that monogamy tends to the welfare of the state, then it is not for the courts of law to sit in judgment upon that decision. Such legislation does not contravene Article 25(1) of the Constitution, the court said.

The legal position enunciated in all the above judgments were reiterated and upheld by the apex court in the Khursheed Ahmad Khan vs State of Uttar Pradesh case (2015). It is to be noted that as per Article 13 of the Constitution, all laws in force or to be enacted must be consistent with the provisions of Part III of the Constitution.

Further, law includes any custom or usage that has the force of law. Thus, marriage laws have to be consistent with fundamental rights under Part III. Polygamy infringes the fundamental rights of Muslim women under Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution.

Moreover, India is also a signatory to various international conventions and covenants such as the UN Committee on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against Women, which notes that polygamy violates the dignity of women and should be abolished.

With inputs from Economic Times and PTI.

The legal position: B

Written by Apurva Vishwanath, May 12, 2023: The Indian Express

Traditionally, polygamy — mainly the situation of a man having more than one wife — was practised widely in India. The Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 outlawed the practice.

IPC Section 494 (“Marrying again during lifetime of husband or wife”) penalises bigamy or polygamy. The section reads: “Whoever, having a husband or wife living, marries in any case in which such marriage is void by reason of its taking place during the life of such husband or wife, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to seven years, and shall also be liable to fine.”

This provision does not apply to a marriage which has been declared void by a court — for example, a child marriage that has been declared void.

The law also does not apply if a spouse has been “continually absent” for the “space of seven years”. This means a spouse who has deserted the marriage or when his or her whereabouts are not known for seven years, will not bind the other spouse from remarrying.

The second marriage

Generally, the first wife files a complaint that her husband has remarried. The court will have to look into whether the husband has entered into a legally valid second marriage. This means that the second marriage would have to be performed as per prescribed customs, and the penal provision will not apply for adulterous relationships that do not qualify as valid marriages under the law.

In Kanwal Ram and Ors v The Himachal Pradesh Administration (1965), the Supreme Court reiterated the legal position that the standard of proof must be of marriage performed as per customs. “In a bigamy case, the second marriage as a fact, that is to say, the ceremonies constituting it must be proved…”

Section 495 of the IPC protects the rights of the second wife in case of a bigamous marriage. It reads: “Whoever commits the offence defined in the last preceding section (i.e. Section 494) having concealed from the person with whom the subsequent marriage is contracted, the fact of the former marriage, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to ten years, and shall also be liable to fine.”

Under Hindu law

After Independence, anti-bigamy laws were adopted by provincial legislatures including Bombay and Madras. The Special Marriage Act, 1954, was a radical legislation that proposed the requirement of monogamy — subsection (a) of Section 4 of the SMA (“Conditions relating to solemnization of special marriages”) requires that “at the time of marriage…neither party has a spouse living”.

Parliament passed the Hindu Marriage Act in 1955, outlawing the concept of having more than one spouse at a time.

Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs are also included under the Hindu Marriage Code. The Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936, had already outlawed bigamy.

Section 5 (“Conditions for a Hindu marriage”) of the Hindu Marriage Act lays down that “a marriage may be solemnized between any two Hindus, if…[among other conditions] neither party has a spouse living at the time of the marriage”.

Under Section 17 of the HMA bigamy is an offence, “and the provisions of sections 494 and 495 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860, shall apply accordingly”.

However, despite bigamy being an offence, the child born from the bigamous marriage would acquire the same rights as a child from the first marriage under the law.

A crucial exception to the bigamy law for Hindus is Goa, which follows its own code for personal laws. So, a Hindu man in the state has the right to bigamy under specific circumstances mentioned in the Codes of Usages and Customs of Gentile Hindus of Goa.

These circumstances include a case where the wife fails to conceive by the age of 25 or if she fails to deliver a male child by the age of 30. However Goa Chief Minister Pramod Sawant has said that the provision for Hindus is virtually “redundant” and that “no one has been given the benefit of it since 1910”.

Under Muslim law

Marriage in Islam is governed by the Shariat Act, 1937. Personal law allows a Muslim man to have four wives. To benefit from the Muslim personal law, many men from other religions would convert to Islam to have a second wife.

In a landmark ruling in 1995, the Supreme Court in Sarla Mudgal v Union of India held that religious conversion for the sole purpose of committing bigamy is unconstitutional. This position was subsequently reiterated in the 2000 judgment in Lily Thomas v Union of India.

Any move to outlaw polygamy for Muslims would have to be a special legislation which overrides personal law protections like in the case of triple talaq.

Prevalence of polygamy

The National Family Health Survey-5 (2019-20) showed the prevalence of polygamy was 2.1% among Christians, 1.9% among Muslims, 1.3% among Hindus, and 1.6% among other religious groups. The data showed that the highest prevalence of polygynous marriages was in the Northeastern states with tribal populations. A list of 40 districts with the highest polygyny rates was dominated by those with high tribal populations.

Second spouse, kin cannot be prosecuted under bigamy law: HC

March 29, 2024: The Times of India

Bengaluru: Only a person who marries for a second time during the subsistence of his/her earlier marriage and the lifetime of the earlier spouse can be prosecuted and punished for bigamy under IPC section 494, not the second spouse or his/her family members, Karnataka high court has ruled. Justice Suraj Govindaraj made this clear while quashing proceedings pending before a judicial magistrate first class court in Chitradurga under section 494 against the petitioners — the parents and sister of a woman married to a person, whose first marriage was still subsisting. The petitioners, residents of Hulugindi in Chikkamagaluru district, had challenged the proceedings initiated on a complaint lodged by a govt hospital nurse against her husband, his second wife and friend. The parents and sister of the second wife were also named in the complaint on the ground that they had participated in the marriage, knowing well that the groom’s marriage with the complainant was subsisting. The petitioners said they could not be prosecuted under section 494 as it was applicable only to the person who had committed the offence. The complainant first wife, however, argued that because of the petitioners’ participation, the second marriage had taken place, leading to the offence under the said provision.

Justice Govindaraj, in his order, said section 494 stipulated that whoever marries during the lifetime of his/her husband/wife shall be punished with imprisonment for up to seven years, but “does not even contemplate prosecuting the person who the husband or wife has married, let alone the father, mother and sister who had participated in or attended the said second wedding”.