Coffee: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

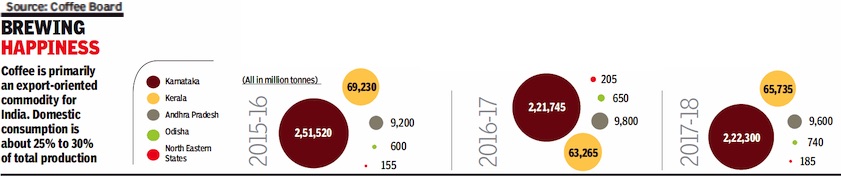

Consumption

2015-18

From: February 9, 2019: The Times of India

See graphic:

Indian states that consumed the most coffee in 2015-18

In Delhi, 2009-10

The Times of India, Mar 5, 2016

Durgesh Nandan Jha

Excessive intake of caffeine has been linked to bad health. But do children care? A survey conducted by University College of Medical Sciences (UCMS) in three Delhi schools has revealed that on an average students take 121 mg caffeine daily, mainly in the form of coffee and tea.

It is much higher than the average intake reported among teenagers in developed countries. In US, for example, the average consumption of caffeine for 12-16-year-olds is 64.8 mg daily and for 17-18-year-olds 96.1 mg daily, according to National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-10 data.

"The survey was part of a student project under ICMR. We did not look for health implications in the students. However, there are enough studies to prove excessive caffeine intake can have a negative effect in terms of optimal sleep and overall growth and development. It also ups the risk of engaging in risky behaviours," said Dr Piyush Gupta, professor of paediatrics at UCMS. He added that tea and coffee were the most common sources of caffeine but a few students also consumed energy drinks.

In the survey, published in the latest issue of the Indian Journal of Community Medicine, the researchers found 97% students took caffeine in one or the other form. At least 6% reported taking more than 300 mg of caffeine daily, which is higher than the maximum permissible limit. "Most students said they consumed caffeinated products to be more alert and to combat drowsiness," Dr Gupta said. Dr Ashok K Omar, director, non-invasive cardiology at Fortis Escorts Heart Institute, said amount of coffee intake increases during exam time and stress. "It is observed that more caffeine children take, the less they sleep, resulting in sleep disturbance. The effect of caffeine is worst in the children who have anxiety disorder," he said.

Apart from coffee, caffeine is found in tea, cola beverages, energy drinks and certain medicines also. "A mug of instant coffee contains about 100 mg of caffeine. The general advice is that adults should not have more than three to four cups of coffee daily and students not more than two cups," said Dr Anoop Misra, chairman. Fortis C-doc.

Caffeine, experts say, also enhances the preference for sweet foods and leads to an overall greater incidence of being overweight. There are more direct effects on neural, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal functions.

Recipes

Filter coffee

March 10, 2024: The Indian Express

To pay homage to this delicious drink, Taste Atlas, a popular food guide, recently released a list of the ’10 Best Rated Coffees’ in the world. While the list was topped by ‘Café Cubano’ — a sweetened espresso shot prepared using dark roast coffee and sugar — our very own ‘Indian filter coffee’ came in the second position.

But what makes Indian filter coffee unique? We reached out to chefs to understand.

What sets Indian filter coffee apart is its distinctive blend of coffee beans, typically a combination of Arabica and Robusta varieties sourced from the lush plantations of South India. “These beans undergo a meticulous roasting process, often with a touch of chicory, to enhance the depth of flavour and impart a subtle bitterness to the brew,” Biswarup Chatterjee, executive chef at Hilton Garden Inn, New Delhi, tells indianexpress.com.

The brewing process itself is an art form, with skilled artisans mastering the technique over generations. “The slow drip method ensures that the coffee grounds are fully saturated, extracting maximum flavour and aroma without compromising on the smoothness of the final cup. The addition of frothed milk, known as ‘decoction’, further enhances the richness and creaminess of the coffee, creating a sensory experience that captivates the palate,” Chatterjee adds.

In comparison to the regular cup of coffee, Indian filter coffee, or filter kaapi, has more caffeine.

“Regular coffee tastes a little bit lighter than filter coffee, which is renowned for having a deeper flavour. While we use processed and refined coffee beans to make normal coffee, we utilise fresh, ground coffee beans for filter coffee preparation. Making filter coffee takes longer than creating standard coffee drinks like cappuccino and espresso because filter coffee is prepared slowly.” says Diwas Wadhera, executive chef, Eros Hotel, Nehru Place, New Delhi.

“Indian filter coffee is also thought to be rich in antioxidants and high in fibre, which may help prevent heart disease, cancer, and other ailments,” he adds.

It also has a special ritualistic way it is often served, says Dheeraj Mathur, cluster executive chef, Radisson Blu Kaushambi, Delhi NCR.

Making Indian filter coffee involves a specific set of ingredients and a unique brewing process. Here’s a simple recipe, courtesy chef Mathur:

Ingredients

Coffee powder: A blend of dark-roasted coffee beans, often mixed with chicory. The ratio of coffee to chicory varies based on personal preference (commonly 80:20 or 70:30).

Water: Fresh, clean water for brewing.

Milk: Whole milk is traditionally used for a richer flavour.

Sugar: Optional, based on individual taste preferences.

Method

Brewing the coffee decoction:

Add 2 to 3 tablespoons of coffee powder to the upper cup of the filter.

Gently tamp down the coffee powder using the plunger or a flat spoon, ensuring it’s compact.

Pour hot water over the tamped coffee powder. Let it percolate through the tiny holes into the lower cup. This process extracts a strong coffee decoction.

Allow the collected liquid (decoction) in the lower cup to fill and set it aside.

Making filter coffee:

Heat the desired amount of milk. Traditionally, whole milk is frothed to create a creamy texture.

In a tumbler, combine the desired amount of coffee decoction with hot, frothy milk.

Adjust the ratio based on personal taste preferences. If desired, add sugar to the coffee-milk mixture according to taste.

For the traditional experience, pour the coffee from the tumbler to the dabarah (saucer) and back a few times to cool and froth it.

Your Indian filter coffee is ready to be enjoyed!

Pro tip: The quantities of coffee, milk, and sugar can be adjusted based on individual preferences. The key is to achieve a balance that suits your taste.

GI tags

Baba Budangiri, Coorg, Wayanad Robusta, Chikmagalur, Araku Valley: applied for

Shenoy Karun, India’s ‘first coffee’ brews GI tag, January 6, 2018: The Times of India

Baba Budangiri, 250 km from Bengaluru, where coffee was first grown in India, is going for Geographical Indication (GI) of its variety of the Arabica brew.

On January 1, the Coffee Board filed an application for the GI tagging of Baba Budangiri Arabica and four other varieties — Coorg Arabica, Wayanad Robusta, Chikmagalur Arabic and Araku Valley Arabica — with the Geographical Indication Registry at Chennai.

Coffee Board head (coffee quality) K Basavaraj said: “We have applied for the GI marker and we are also profiling the majority variety grown in Baba Budangiri, a variety called Selection-795,” Basavaraj said. Selection-795 (S-795) is considered to be the natural descendant of two of the oldest African cultivars of coffee — Coffea Arabica and Coffea Liberica — and a third variety is called Kent. Currently, S-795 is the most prominent coffee grown at Baba Budangiri.

Edmund Hull in his book ‘Coffee Planting in Southern India and Ceylon’ says that Coffea Arabica originated in Caffa in southern Abyssina and then found its way to Yemen. According to John Shortt’s ‘A Handbook on Coffee Planting in Southern India’, Baba Budan (Baba Booden), a Muslim pilgrim, brought the brew from Mocha, a port city in Yemen, in the 17th century and introduced the variety in the uninhabited hills that came to be known as Baba Budangiri.

Today, Baba Budangiri Arabica is grown acorss 15,000 hectares around the original hills, where it was first planted. Over the last few centuries, coffee plantations grew beyond Baba Budangiri and the adjoining Chickmagalur and spread to Kodagu and Hassan in Karnataka, and Wayanad, Travancore and Nelliampathy regions of Kerala. It is also grown in the hilly regions of Palani, Shevroy, Nilgiris and Anamalais in Tamil Nadu. The non-traditional areas of coffee-growing in India includes certain pockets in Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland.

Production

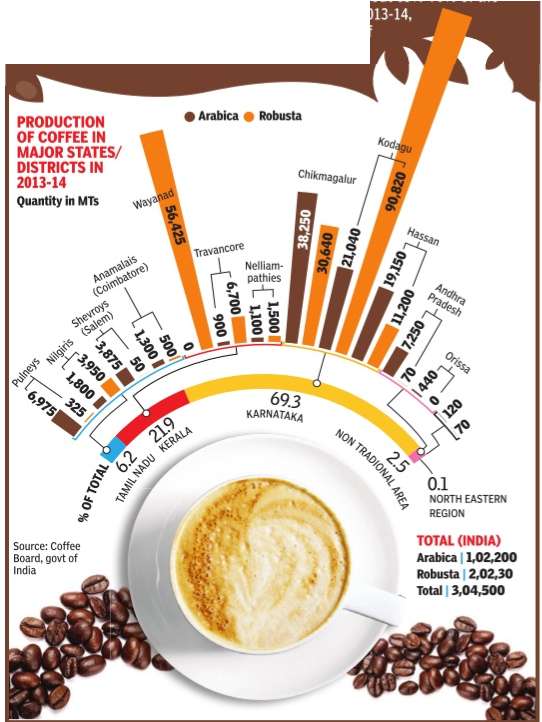

2013-14

Feb 24 2015

According to the Indian Coffee Board, the first planting of coffee in India happened in 1600 CE when saint Baba Budan planted seven seeds of mocha in the courtyard of his hermitage in Karnataka. Commercial plantation started during the 18th century. Traditionally, it is grown in the Western Ghats spread over Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. Coffee is grown predominantly as an export commodity in India as about 65%-70% of the total coffee produced in the country is exported. In 2013-14, the total production was over 3 lakh metric tonnes, of which about 70% was produced in Karnataka alone.

Types of Indian coffee

Arabica/ Robusta coffee

Positive impact on diversity of wild birds

From: Aathira Perinchery, Arabica coffee helps both farmers and wild birds in the Ghats, February 16, 2018: The Hindu

Coffee lovers may be discerning about their sweet arabica brews and the bolder robusta ones, but both types help maintain the diversity of wild birds in the Western Ghats. One, a little more than the other.

Arabica grows under the deep shade of native trees, with benefits for both farmers and birds. The surprise is that Robusta, also grown under native shade, is not far behind in the Ghats, unlike in other parts of the world.

These insights from a group of researchers were published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Native trees are cut down to grow robusta, in order to give it more sunlight, earning this coffee the tag of being inhospitable to wildlife. In Vietnam, for instance, full-sun coffee growth occurred at the expense of native trees. India too has leaned towards robusta: between 1950 and 2015, planted area under robusta grew by 840% while arabica grew by 327%.

Scientists from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS-India) and USA’s Princeton University compared bird diversity in 61 arabica and robusta estates across Chikkamagaluru, Hassan and Kodagu districts in Karnataka.

Some surprises

What they found is that the plantations supported 79 species of forest-dependent birds in all, but arabica estates hosted twice the number of endemic birds than robusta. They also supported more birds that depend on forests, and eat fruits, insects and other food. Interviews with 344 coffee-growers showed that arabica was more profitable, with returns of around ₹1 lakh per hectare.

Yet, surprisingly, robusta plantations also hosted high bird diversity. “To our surprise, robusta agroforests had much higher diversity of birds that are specifically adapted to the habitat than we expected,” says scientist Krithi Karanth of WCS-India, who led the study.

Since robusta farmers in the Western Ghats retain native trees, they have been able to preserve the complex canopy structure, setting them apart from others worldwide, says Ms. Karanth.

“Though the current selling rate for robusta is only around ₹3,000 for a 50-kg-bag, it is easier to grow,” explains Suresh M. D., who owns a one-acre coffee plantation of both coffee types.

Araku Valley coffee

One hears of cooperative farming where government, NGOs or corporate entities provide resources or knowhow to support cultivation. But in the picturesque and protected Araku Valley of Andhra Pradesh, a unique agri enterprise has taken shape. Tribals from this region, with the backing of four business leaders, are growing top-notch quality coffee, which made its debut overseas under an exotic brand.

Anand Mahindra (chairman, Mahindra & Mahindra), Kris Gopalakrishnan (co-founder, Infosys), Satish Reddy (chairman, Dr Reddy's Laboratories) and Rajendra Prasad Maganti (chairman, Soma Enterprise, a construction company) have joined hands to form an enterprise that will launch Araku coffee's first store in Paris.

For the 150-odd tribal communities living in the Maoist-infested belt, the global debut is a big step forward. Until 15 years ago, their life was dependent only on collecting forest produce. A predominantly tribal area (including the Bagathas, Valmikis Kondus and Poorjas) in Visakhapatnam district, the Araku region is classified as an agency area; the government has cre ated a special developmental and fun ding plan for locals. All the land here be longs to the government and a tribal is entitled to get land as much as she can till for free, to earn a living.

Coffee cultivation is not new to the area--the British did it and the govern ment continues to grow the beans under its own brand, but it was only in the re cent past that tribals tried their hand at it on a large scale. From 1,000 acres some years ago, the land under coffee produc tion has gone up to 20,000 acres.

The four investors have stepped in to assist them in increasing bean produc tion by roping in global experts. “We want to make Araku a gourmet coffee brand, acceptable in global markets and that's why we chose Paris for the debut,“ , Mahindra told TOI, adding that the pro fits made from the venture will be ploug hed back to improve the quality of the farmers' lives.Araku will be sold under five variants with the most expensive stock pri ced around Rs 7,000 a kg. The steep price can be justified by the fact that this is per haps the first time in the world that cof fee is being produced using techniques similar to those in wine making. Like unique tastes of different wines identified by the soil in which the grapes are grown, the variants of Araku coffee also draw their flavours from the `terroir' or unique environment.

“Araku coffee is unique because of its complex terroir and that's why premi um. Everybody wants a simple life but they pay for complex things. Luxury is all about complexity,“ Mahindra said.

Araku coffee was originally a nonprofit venture supported by Naandi Foundation, the brainchild of Andhra Pradesh chief minister Chandrababu Naidu and Anji Reddy , founder of Dr Reddy's. The late Reddy brought Mahindra into Naandi and the chairman of the au to major, along with the other three investors, soon transformed the social enterprise into a for-profit venture.

“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime. All these are passe. I believe it is now time for private enterprise at shared value, which I call 3.0,“ Mahindra said.

Araku coffee has already got a geographical indication (GI) tag, which authenticates the unique properties a region can offer to a product. But until now, the Arabica coffee produced by the tribals was being sold in bulk to roasters who were ready to pay a premium for this brew.

Plan is to launch the next set of retail stores in New York and Tokyo. Which means the world famous Columbian and Sumatra coffees will soon have competition on the shelf from a little-known region called Araku in India.

Darjeeling

2024

Joel Rai, June 16, 2024: The Times of India

To the north of Darjeeling town, two spurs descend steeply to the Rangeet, the river whose snaky course forms the boundary between Sikkim and West Bengal. Rising from the left bank of the river on the Darjeeling side are the tea gardens of Badamtam, Ging, Singla and Vah Tukvar and the hamlets of Limbu Busty and Lapchey Busty. The coiffeured look of the tea estates is broken on the fringes by unpruned bushes — dark green, waxy leaves with wavy edges, adorned at certain times of the year with deep red berries.

Mention of Darjeeling makes you think of the volatile oils of the tea plant serenading your olfactory nerves and waltzing with your taste buds. But if that’s all that the name evokes, it’s time to wake up and smell the coffee. For the raggedy clumps spoiling the serenity of the tea gardens are coffee plants.

There now are many of these coffee clusters across the hills of Darjeeling, Kurseong, Mirik and Kalimpong. Strange, because Darjeeling has been, since the 1860s, a synonym for tea, the kind that satisfies the soul, attracts eye-watering prices and makes you preen when you offer it to special guests. But now these hills are home, too, for this interloper — a beverage that is as body as tea is not, as tinged with acid as tea is not, as different as a French press is from a china pot. The debate might only be on which gives off a more energising aroma.

Late Bloomer

Take a sip. Coffee from the land of tea is making itself heard and tasted, slowly but surely. From around a decade ago, when some people casually planted the seeds and found the cherries ripening to produce beans, indigenous coffee is now being sold in cafes in the tourist hubs in the region, in souvenir shops alongside packets of tea, and on ecommerce sites. Umesh Gurung, a barista, certified coffee roaster and quality controller from the Coffee Board of India not only offers his own Himalayan Cornerstone coffee at the Andante Café in Siliguri, opened in 2019, but also on Amazon and Flipkart. Sanjog Dutta, owner of Daammee.com, which sells specialty items from the region, regularly dispatches hill coffee to customers in different parts of the country. Altura Coffee in Darjeeling has also grown from a small café to a big player, in relative terms, as has Himali Highland Coffee in Kalimpong.

Hill coffee is still minuscule, with a production of around a puny 10.5 tonnes all told against the 3.4 lakh tonnes of the bean that India produces, mainly in the south. Like foam and latte, the adventure in tea land boils down to the teamwork between farmers and processors/roasters. The coffee is grown by farmer collectives on their micro-holdings, often in their traditional homes in tea gardens. They have no means or expertise for processing the cherry they grow. That important task is left to the entrepreneurs who, despite lack of investment, have made a good beginning.

Gurung had his epiphany on a 2014 trip to the Nepal border, where he saw coffee being produced by the neighbouring country. With the geography almost identical, he wondered why they shouldn’t experiment with the popular beverage at home. From that realisation a decade ago, Himalayan Cornerstone this year produced 6,500kg of good coffee. Induction of South Korean coffee expert, Young Gyu Seo, has brought in much-needed expertise in processing and roasting.

Serendipitous Start

For Rishi Raj Pradhan of Himali Highland, it was unplanned destiny. In 2014, he was given four Arabica saplings by coffee expert Llewellyn Tripp of Australia, who’d stayed at Rishi’s homestay in Kalimpong. Owing more to curiousity than to any whiff of opportunity, Rishi saw the plants to maturity in 2017, harvested around 2kg of beans and, with uneducated guesses, blundered through the roasting. Encouraged, he planted more saplings. Today, his home plantation grows 400 Arabica varietals and 1,000 hybrid Chandragiri plants. He produced 650kg of coffee this year. Amazingly, besides regular advice from Tripp, Rishi’s journey has mostly been experiential, his entire knowledge acquired on the internet and from reading the literature and conversations with experts.

Altura’s Vikash Pradhan had an even more compelling reason for plumping for his own coffee setup. The café that he founded along with his two partners, Prayash Pradhan and Raman Shrestha, in the tourist magnet of Darjeeling town had a Lavazza machine. In 2010, it broke down and nothing they did could get either the machine working or the company rushing to remedy the situation. After going without coffee on the menu for a couple of years, a café worker told Pradhan in 2013 that he had a few coffee plants at his home on the outskirts of Darjeeling town. On a lark and relying on YouTube for knowhow, Pradhan and his partners roasted a handful of the locally grown beans. When it passed muster, rather eminently, the thought that they wouldn’t have to rely on imports from the plains urged the group to try their hand at producing coffee themselves.

Even the coffee farmers took to the bean for reasons other than coffee itself. Sunil Subba, who heads the Darjeeling Coffee Committee that oversees the efforts of over 70 households growing coffee, smiles when he says, “I am actually involved in the welfare of the poor tea garden workers, particularly their education and health. With the tea gardens in poor health in recent years, and the cash crops of oranges and cardamom failing frequently, I was looking for ways in which the affected families could supplement their income. Coffee came at an opportune moment.”

Subba’s group began in 2016, with some of them getting trained in growing coffee in Nepal and at workshops in Darjeeling. “It takes around four years for a plant to start producing fruit that can be made into coffee,” he says. This year, they grew 3,500kg of coffee cherries with Subba saying that “from a handful of plants, now our members have 1.7 lakh bushes; next year, our harvest might go up to 8,000kg”.

Way To Grow

In Kalimpong, where the local Gorkhaland Territorial Administration conceived of coffee to replace the outdated cinchona and utilise the vast holdings and the quinine factory infrastructure at Mungpoo, coffee growers had a baptism by fire. GTA, in partnership with the Bengal horticulture department and Directorate of Cinchona and other Medicinal Plants, distributed saplings in 2019, but the enthusiastic farmers found that the plants could not stand the dew. They lost a large portion of the saplings. Starting all over, they are on a better footing today with private processors and roasters buying their cherries.

Arjun Rai, lead farmer at Sangse Busty, says his group brought in 1,100kg of parchment, which is coffee fruit with the fleshy exterior removed. Parchment has to further undergo removal of a layer before its two beans can be extracted for roasting.

Lack of funds has been a problem, but the companies have gamely weathered the storm. Altura’s Pradhan says, “While the bigger players elsewhere are solving problems with capital and investments, we are trying to find innovative solutions within our means.” He talks about how they overcame the problem of the varying ambient temperature in Darjeeling between November and April, which affects fermentation and resulted in differing flavours across batches even with the same fermentation period. “Big players have climate-controlled rooms and vats. All that is beyond us. But we have devised our own system that does not cost much and also makes uniform fermentation possible,” he says.

So does coffee made in a teapot enthuse connoisseurs? “Samples sent across the country and abroad have garnered rave reviews,” claims Gurung. Daammee’s Dutta says, “Since the production is not too big, the costs involved are steep. That could be one of the reasons why things are picking up slowly, though I must say the quality of the Arabica is exceptional.”

As for the future, Vikash Pradhan says coffee can be commodity or specialty, the former a low margin, high-volume crop like in south India, the latter low-volume but high quality. “The quality of a coffee is measured as a cupping score and 80+ is considered specialty,” says Pradhan. “This model requires intensive action and monitoring right from varietal selection to land, growing, processing and roasting. We are looking to have at least one cupping champion in the coming three or four years.

“Arabica coffee, as a crop, loves altitude but a single night of frost can decimate a plantation. We did some research and figured out that the latitude where we belong gives us unique growing conditions. So, as of now, we believe that we need to start labelling our local coffee as ‘High Latitude’ rather than ‘High Altitude’.” Add attitude to that. Can’t you hear Gurung, Vikash Pradhan, Rishi Pradhan, Dutta, Subba, Rai and all the farmers grinning and saying, “Bean there, done that”?

Coffee brand Altura’s founder Vikash Pradhan got going after a worker at his cafe told him in 2013 about some coffee plants at his home on the outskirts of Darjeeling town. Relying on YouTube for knowhow, Pradhan and his partners roasted a handful of the locally grown beans. When it passed muster, the thought that they wouldn’t have to rely on imports from the plains urged the group to try their hand at producing coffee themselves.

Umesh Gurung, a barista and certified coffee roaster, had his epiphany on a trip to the Nepal border in 2014, where he saw coffee being produced by the neighbouring country. With the geography almost identical, he wondered why they shouldn’t experiment with the popular beverage at home. From that realisation a decade ago, Himalayan Cornerstone — the brand he retails online and at his Andante Cafe in Siliguri — this year produced 6,500kg of good coffee.

YEAR-WISE DEVELOPMENTS

2024

Decreased production in key countries leads to high returns for India

ManuAiyappa Kanathanda, April 13, 2024: The Times of India

From: ManuAiyappa Kanathanda, April 13, 2024: The Times of India

Bengaluru: Robusta coffee bean prices, a staple of India’s coffee production and a key ingredient in the creation of instant coffee, have surged to unprecedented heights, reaching an astounding Rs 10,080 per 50 kg bag as of Friday. This is the first time prices have soared to such heights since the inception of coffee estates by the British in the picturesque hills of the Western Ghats (Malnad) region of Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu around the 1860s.

Unlike its esteemed counterpart, the Arabica variety, renowned for its capacity to produce a luxuriously creamy layer atop a shot, the robusta has maintained a comparatively stable price range of Rs 2,500 to Rs 3,500 per 50 kg bag for almost 15 years.

The unprecedented surge in coffee prices has elicited smiles among coffee growers, particularly those with smaller holdings, as they predominantly cultivate the robusta variety due to low input costs when compared to Arabica. These growers have endured a decade-long struggle marked by losses stemming from challenges such as erratic rainfall, crop damage inflicted by wild animals, and escalating input and labour costs.

“Till last year, we were fetching Rs 4,500 per 50 kg bag. By Jan this year, prices had surged to Rs 7,000 to Rs 8,000, contingent upon the outturn (the ratio between harvested coffee and its processed grains). I never imagined, even in my wildest dreams, that prices would reach the Rs 10,000-mark,” said G Nithin, an elated coffee planter in Chikkamagaluru who’s partially sold his stock in anticipation of further price climbs.

Nanda Belliappa, chairman of the Codagu Planters Association, established in 1870, attributed the historic surge in robusta coffee prices to the fundamental principles of supply and demand. He noted that decreased coffee production in key robusta-producing countries like Brazil, Colombia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Honduras, and Ethiopia — due to adverse weather conditions such as drought and frost — as well as changes in cropping patterns, contributed to a windfall for Indian growers. “The increased global demand for coffee, particularly among the younger generation, has also played some small role in driving up prices,” Belliappa added.

Sources within the Coffee Board of India added that the price surge is also attributed to major robusta coffee growers like Vietnam and Indonesia transitioning to different crops such as dragon fruits and avocados, which yield higher profits compared to coffee. Additionally, they noted that coffee is expe- riencing increasing demand in the cosmetics industry. In India, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu collectively contribute to 83% of the coffee production, with Karnataka alone accounting for 70% of the total output.

Within Karnataka, coffee cultivation is concentrated in three districts: Kodagu, Chikkamagaluru, and Hassan. Kodagu a lone constitutes 6 0% of the production, while Chikkamagaluru and Hassan contribute to the remaining 40%.

Over the past decade, coffee plantations in Karnataka have experienced a downward trajectory, with farmers compelled to sell their land to real estate developers or convert it into tourism ventures. This shift can be attributed to diminishing returns, driven by low coffee prices and escalating input costs, which have undermined the profitability of this cash crop. The labour shortage on coffee plantations is a significant driving factor.

“There i s a severe scarcity of skilled workers to tend to the estates, coupled with a steep increase in labour costs. In contrast to the Rs 50 to Rs 150 daily wage offered in the early 2000s, labourers now command Rs 500 to Rs 700 per day, depending on the complexity of the task,” explained Somaiah.

Somaiah elaborated further: “Coffee growers historically relied on local tribal communities for labour, but their population has dwindled over time. This has prompted growers to increasingly depend on migrant labourers from Bengal and Assam, largely because they bring experience from working in tea estates there.”

Planters have contended with losses inflicted by wild animals due to their proximity to forests. “While elephants & bisons stray into the estates in search of food and water, damaging the coffee plants, swarms of monkeys and giant squirrels enter the plantations and pluck the berries to suck the sweet pulp,” lamented A C Ponnappa, a planter from Kodagu, highlighting the challenges posed by wildlife.