Sariska Tiger Reserve, Sarunda

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

The status of tigers and STR itself

2008 – 23

Ajaysingh Ugras, July 16, 2023: The Times of India

From: Ajaysingh Ugras, July 16, 2023: The Times of India

From: Ajaysingh Ugras, July 16, 2023: The Times of India

In May 2005, a CBI report tabled in Rajya Sabha revealed there were no tigers left in Rajasthan’s Sariska Tiger Reserve (STR), although a year earlier a census had estimated their number at around 15. “The entire tiger population seemed to have become extinct primarily because of poaching,” Namo Narain Meena, then minister of state for forests, had told the House.

Almost two decades on, Sariska – the sole tiger reserve in the National Capital Region – has bounced back. “STR has since undergone an extraordinary transformation,” says Sunayan Sharma, retired IFS (Rajasthan), who has written a book about it titled ‘Sariska: The Tiger Reserve Roars Again’.

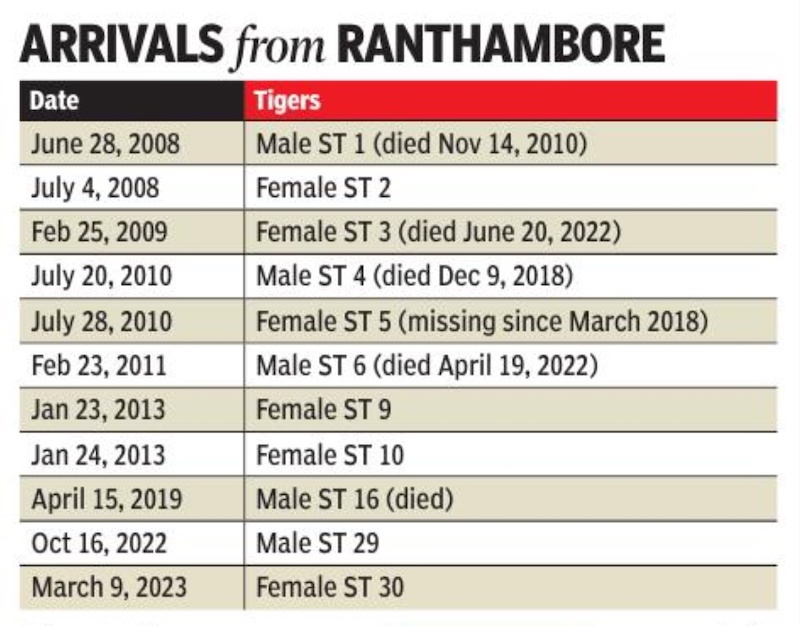

At the last count, STR had 30 tigers – 10 females, 7 males and 13 cubs, of which 17 were born in Sariska. The revival happened after India’s first tiger translocation programme that brought in 11 tigers from Ranthambore. Success seemed unlikely at first when “out of the 11 relocated big cats, two fell victim to poaching, and four females failed to deliver cubs due to human disturbance, rampant mining, and other factors,” says Dinesh Durani Verma, founder of Sariska Tiger Foundation.

“It took over a decade for the tiger population to flourish in Sariska. Since 2020, 17 tigers have been born inside the park, which is a positive indication,” Verma adds.

The STR had to overcome significant challenges to make the turnaround, says Sharma. For example, when the tiger population had plummeted in the 2000s, the local panchayat had started demanding permission to develop plots within the reserve. This would have effectively shut the door on tiger reintroduction.

But now, not only the tiger population but also the reserve’s ecological balance is being restored as the forest department is reintroducing species that had become extinct in the region. A pair of sloth bears has been introduced, as they play a vital role in maintaining the ecosystem. “They are essential for propagating large and seeded tree species. Also, the introduction of more wildlife species is expected to attract a greater number of tourists. Plans are underway to reintroduce wild dogs, which were once native to the reserve,” a senior official told TOI.

Next, the STR will add 600 sq km to its area to provide more protected space to the big cats. The proposal was approved at the first technical committee meeting of the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), and a window was left open for further expansion after feasibility studies.

Demonstrating its commitment to the reserve, the administration has already shifted out four of the 26 villages situated inside it, and is now relocating another village. To ensure the wildlife is not disturbed by traffic, a soundproof elevated road will also be made.

“The reserve has the potential to accommodate over 50 tigers. So, the relocation of villages and remapping of the area should be prioritised,” says R N Mehrotra, former chief wildlife warden of Rajasthan, adding, “The recent shifting of villages has created a secure space for the ti gers, and the results are evident. The Centre should also contribute funds to shift the villages. ”

The new road between Delhi and Sariska will boost tourism as more people will be able to visit the reserve. Experts say this will help garner support for the STR from a wid er group of people. It will also facilitate better monitoring of the reserve and encourage the involvement of the local community.

Luv Shekhawat, owner of a small hotel in Tehla near the STR, says, “With more tigers and improved connections, hotels in the area are thriving. People involved in the reserve are working hard to protect the animals and educate the locals. Our team is creating jobs for villagers and partnering with NGOs to teach skills useful in the reserve. ”

As in 2019

From: Anindo Dey & Ajay Singh Ugras, A gender skew threatens future of tigers in Sariska, March 9, 2019: The Times of India

Park Hit By Fund, Staff Crunch; Shifting In Males May Not Work

It has been a long journey for a soulmate — and a hectic week — for tigress ST-9. From deep within the Sariska Tiger Reserve (STR) at Sarunda, the tigress travelled to Chamari Ka Bera, 25km away near the entrance to the park, in search of a male. But the journey proved futile.

The sole male tiger in the zone, ST-6, is ageing and at least four other females are looking for him. Wildlife experts believe that the tigresses may soon leave the reserve in search of a mate. That would be disastrous for the tiger reserve.

Compared to the flourishing Ranthambore Tiger Reserve (RTR), lack of political will and years of stepmotherly treatment have hit Sariska so hard that if immediate corrective steps are not taken, the dream of seeing its big cat population sustain and grow after the first tiger was relocated in 2008 might just fade away.

“There is an urgent need to relocate a male tiger,” says wildlife enthusiast Abhimanyu Singh Rajvi, a frequent visitor to STR.

Recently, male tiger ST-4 died in a territorial fight with ST-6, the third death after the reserve was repopulated in 2008. ST-1, the first tiger brought from Ranthambore, also a male, died in 2010 after villagers poisoned it. On March 19, 2018, four-year-old male tiger ST-11 died after getting entangled in a barbed wire fence laid by a villager close to a forest post adjoining Sariska.

Currently, the park has three males, eight female tigers and eight cubs, with ST-6 the dominant male.

“If steps are not taken to ensure that the tiger gets regular food, ST-6 may not survive. ST-6 is a famous tiger. After launching one of the worst attacks on the then RTR ranger Daulat Singh Shekhawat, it had gone for a long walk to Uttar Pradesh before returning from Bharatpur. With him gone, we will lose another male,” said Dinesh Verma Durani, founder and general secretary of Sariska Tiger Foundation and a member of the advisory committee for Sariska.

An option is to relocate male tigers from Ranthambore, which has a skewed sex ratio in favour of males, forcing many sub-adults to stray away. But not all think so. “While relocation to Sariska seems a bright idea, we will not be able to monitor the animal with our limited infrastructure. There is no inviolate space for a male tiger as villages have not been relocated from the reserve for long. A new male tiger without a marked territory may also pose a threat to cubs here,” said STR divisional forest officer Hemant Singh Shekhawat.

With 40 home guards that the park had for patrolling having left after not receiving pay for nine months, the park is short of staff and has 11 off-roaders in poor condition to monitor the entire reserve.

In 2005, an empowered committee, headed by the then parliamentarian V P Singh had highlighted more than 20 issues for the welfare and effective monitoring of Sariska. The panel had recommended three guards in one beat. Ideally, there should be 400 guards based on the committee’s suggestion.

Residents of only three of the 29 villages inside the reserve have been relocated, the last one way back in 2013. The post of DFO (relocation) has been vacant since 2014 with people being deputed temporarily for the job.

“The villagers have political patronage. Local leaders were against shifting as it would affect their vote banks. Moreover, the concept of villagers shifting voluntarily does not work,” said a forest official.

According to the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), Rs 7.12 crore was sanctioned in 2018-19 for the reserve. The amount is shared by the NTCA and the state government in a 60:40 ratio. Though the NTCA had handed over its share, the state government has only released Rs 2.56 crore so far. “For the protection of tigers in an area of over 1,250 square km, the government has released less than half the sanctioned funds. How can effective monitoring be done,” said an official.

“For reasons of poor connectivity and lower sightings of tigers, Sariska has its disadvantages as far as tourism is concerned compared to Ranthambore. But to correct this, the forest department should open all dedicated zones to improve the frequency of sightings. That will then go a long way in improving the condition of the reserve,” says Durani.

The apathy of the government is also caused by a strong Ranthambore-based tourism and hotel lobby that sees a flourishing Sariska as a threat to their business. “Tiger T-24 aka Ustad, which was declared a maneater, was earlier proposed to be shifted to Sariska and supposed to stay there in an enclosure. The order was passed and even a vehicle was dispatched to pick up the tiger. But in the last minute, the process was stalled. T-24 in Sariska would have boosted tourism in a big way. Similarly, several requests for relocating a male tiger to Sariska went unheard due to the interference of an influential lobby in the forest department,” Durani added.

“Funds follow performance and Ranthambore has been doing very well compared to Sariska. But sometimes it should also be seen the other way. With better infrastructure, the performance of Sariska will improve. It is high time the state government gives Sariska its due and takes immediate steps for tiger conservation. Ranthambore has the pride of place among all tiger reserves, so there shouldn’t be any fear of competition from Sariska,” said an expert.

Supreme Court orders against illegal mining in the reserve

An The Indian Express history, till 2024 April

Jay Mazoomdaar, May 21, 2024: The Indian Express

The Supreme Court has ordered the Rajasthan government to shutter 68 mines operating within a 1-kilometre periphery of the critical tiger habitat (CTH) of the Sariska reserve. The order, passed on May 15, is the latest of many attempts by the country’s top court since the 1990s to halt the mining of marble, dolomite, and limestone in Sariska in violation of laws.

Both the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and Environment Protection Act, 1986 prohibit quarrying in and around a tiger reserve.

In the 1990s

In May 2005, the SC ordered the CBI to investigate the disappearance of tigers from the reserve in the Aravalli roughly halfway between Delhi and Jaipur. That was almost a decade and a half after the court first took up the issue of illegal mining in Sariska.

In October 1991, in a PIL filed by a local NGO, the SC issued an interim order that “no mining operation of any nature shall be carried on in the protected area” of Sariska, and set up a fact-finding committee under the chairmanship of Justice M L Jain, a retired judge of the High Court.

Based on a “traced map provided by the Forest Department,” the Jain Committee found in 1992 that the protected areas covered “about 800 sq km”. In April 1993, the SC ordered the closure of 262 mines within that area.

In the 2000s

Ten years later, the Central Empowered Committee (CEC) of the SC submitted a damning report on mining around the Jamua Ramgarh Sanctuary which is part of the Sariska tiger reserve. The following year, the NGO Goa Foundation approached the SC with a complaint about a similar situation in Goa.

In September 2005, the SC laid down rules for issuing temporary mining permits in forest areas. In August 2006, it said, “as an interim measure, one-kilometre safety zone shall be maintained subject to the orders that may be made…regarding Jamua Ramgarh Sanctuary”.

But the mines were back in business in 2008 after the Rajasthan government claimed that the sanctuary boundary had been demarcated, and allowed quarries outside the 100-metre periphery of the sanctuary. The state stuck to the 100-metre regulation in its draft Eco-Sensitive Zone (ESZ) notification for Sariska in 2011.

Meanwhile, in January 2002, the Indian (now National) Board for Wildlife had proposed to notify areas within 10 km of national parks and sanctuaries as ESZs. But after several state governments expressed concerns, the Board had asked them, in May 2005, to identify suitable areas and submit proposals for site-specific ESZs.

After many states failed to respond, the SC intervened in December 2006. The court warned that if the states failed to respond within four weeks, it might have to consider the original plan of ESZs of 10-km width.

In the 2010s

In September 2012, the CEC submitted a report on ESZs that went beyond Sariska. In January 2013, it followed up with a supplementary note on the “inordinate delay” in notifying the safety zones.

The SC put its foot down in April 2014. Its judgment in the Goa Foundation case underlined that the August 2006 order “has not been varied subsequently nor any orders made regarding Jamua Ramgarh”, and that “the order…saying that there will be no mining activity within one-kilometre safety zone…has to be enforced”.

But it took another four years for the SC to act on its 2006 order. In December 2018, noting that 21 of the country’s 662 national parks and sanctuaries were yet to submit ESZ proposals even 12 years after the deadline had passed, the court ordered that 10-km belts around them be declared ESZs.

In the 2020s

After the 2003 CEC report, several miners joined the case concerning Sariska’s Jamua Ramgarh sanctuary. The apex court finally ruled on the matter in June 2022. It ordered ESZs of a minimum width of 1 km for all national parks and sanctuaries, but limited it to 500 metres for Jamua Ramgarh sanctuary as a “special case” with some leniency.

After multiple objections to this one-size-fits-all approach, however, the SC modified the 2022 order in April 2023. The modified order left the specifics of ESZs to the Centre and the state, and focussed on mining — prohibiting it within 1 km of national parks and sanctuaries.

On May 15, the SC criticised the Rajasthan government for misinterpreting this order as being not applicable to tiger reserves. The court clarified that the 2023 direction applied to tiger reserves which “stand on a higher pedestal”.

Background of problem

Local people in Sariska have repeatedly demanded the demarcation of forest boundaries on the ground. Villagers have alleged that soft boundaries allow illegal mines to operate legally on paper by showing their locations outside the reserve. Also, to make up for the areas lost to such concessions, revenue villages are alleged to have been arbitrarily included in the tiger reserve, impinging on the rights of residents.

A decade after Sariska became a tiger reserve in 1978, Rajasthan issued mining leases inside the reserve to many who had obtained no-objection certificates (NOCs) from the then field director of Sariska, even though he did not have any authority to issue such NOCs.

In 1993, Rajasthan’s proposal to compensate for these illegal mines by adding 5 sq km of revenue land to the reserve was rejected by the SC. But the ‘swap’ happened anyway, according to two retired forest officials who have served in the Alwar district.

Uncertain boundaries

The area statement records submitted to the SC in 1993 did not tally with the accompanying map. The discrepancies were so glaring that the surveyor was constrained to add a face-saver on the map: “Prepared by me as per the direction of FD (Forest Department), PT (Project Tiger), Sariska.”

In 1999, the Sariska management claimed to have lost several land records. The forest bosses in Jaipur then borrowed the said records from the Revenue Department, which in 2003 claimed these documents were never returned.

In August 2008, when Rajasthan approached the Survey of India to undertake the demarcation work in Sariska, the then state forest head wrote in a letter that “the exact boundary, including the location of pillars, is not known”. Survey of India backed out of the job because Rajasthan failed to provide reliable maps and records.

In the absence of demarcated boundaries, Sariska’s Tiger Conservation Plan could not be finalised until 2014-15 when the state finally prepared a map for “management purposes” with a disclaimer against its legal authenticity.

Another opportunity

A senior official in the Rajasthan Forest Department said the latest SC order was yet another opportunity to thwart illegal mining in the state. “Whatever mistakes were made in the past can be set right by demarcating the no-go zones around Sariska and also other mining-affected reserves of the state,” he said.