Nurses: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Availability of nurses, the state of the profession

2000-2022

August 24, 2024: The Times of India

From: August 24, 2024: The Times of India

I chose nursing because everyone said it was an ideal fit for my personality. My mother is a nurse, too,” says 28-year-old Rusha Shrestha, a nurse who graduated in 2019 from a Gurgaon college. She started work in the middle of the pandemic and is now set on a career abroad, like “almost all the others”, she says.

After Covid, as many countries seek to expand nursing capacity, Indian nurses have gladly filled these spots. “Nursing students now are very clear that their study is an investment for a job abroad. So, half of them will go to the Gulf for work experience, then after a few years, move to the West, which is always the real goal. This is step-migration, in the way one might have a layover in Dubai for a trip to the US,” says migration scholar Irudaya Rajan. Last year, 29,000 nurses from Kerala alone got placed in jobs abroad, says Jibin TC, president of the United Nurses Association.

To move to these destinations, they have to take tests like the OET and IELTS, and the NCLEX for the US and Canada, the Pearson CBT, and so on. Specialised recruitment agencies match aspiring nurses to hospitals and health agencies abroad. Applying abroad takes time and money, with exam fees, verification of credentials and so on — “about Rs 3-4 lakh and one or two years,” estimates Shrestha. But the rewards are worth it. “In Germany, a nurse makes the equivalent of Rs 4 lakh a month, in the US they make at least $75,000 a year,” says Rajkumar Kannaiyan, founder of Metier Training Academy which trains nurses for competitive exams and migration opportunities. “In India, a nurse works 72 hours a week, while in the UK it is 38-42 hours plus overtime and paid holidays,” says Jibin.

“India is a global player in the nursing care market, it is neck and neck with the Philippines, and can even surpass it,” says Rajan. “India’s export of skilled nurses will not only improve women’s work participation, and give them economic and social mobility, it will also bring in higher remittances,” he adds.

Spotting this opportunity, the govt has encouraged nurses to seek global jobs, easing bureaucracy, doing away with emigration clearance requirements (ECR), signing agreements with other countries to mutually recognise qualifications. The National Skill Development Corporation has recently committed to helping nurses learn foreign languages like Japanese and German, to facilitate their job-search.

It All Began In Kerala

In India, modern nursing has its roots in missionary work, and Malayali Christian women were the earliest adopters. Dai or midwife had traditionally been a caste occupation, and the stigma of ‘body’ work and working outside the home made it off-limits for higher caste Hindus and Muslims. It began to be seen as a suitable or desirable career only around the 1980s, says Sreelekha Nair, a social scientist who has studied nursing and migration networks.

While nurses from Kerala and the south were once the majority, the picture is more geographically balanced now. There is also a substantial presence of men, especially in the emergency and critical care areas, where nurses might have to physically lift or move patients.

To meet this growing global demand, there has been an explosion of private nursing colleges across India. As of 2022, there was a total of 5,162 approved institutions, offering GNM and ANM courses, or BSc and postgraduate degrees. Many young people take loans to finance their education.

India Facing Nurse Shortage

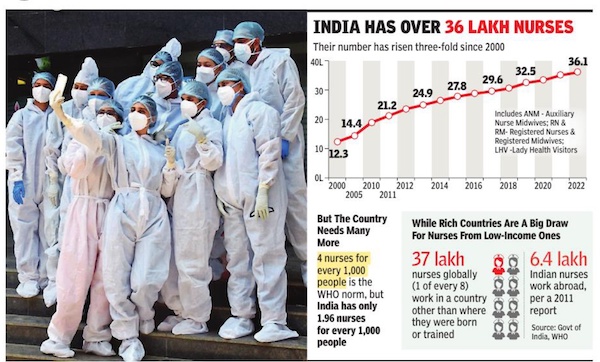

And yet, for the lakhs of nurses it produces every year, India has too few nurses to meet its own needs. India has only 1.96 nurses and midwives per 1,000 people; WHO norms call for four per 1,000. While the Covid pandemicbrought new public attention and applause for nurses, their pay and professional environment are still subpar or actively exploitative here. “People clap for nurses and call them angels, but that isn’t going to feed a family,” says Jibin.

Unsurprisingly, the biggest draw for Indian nurses are govt hospitals. Salaries start at Rs 80,000 and go up to Rs 2.5-3 lakh, says Roy K George, president of the Trained Nurses’ Association of India. There is paid leave, pension, and other benefits, including housing. One can move from nursing officer to assistant superintendent, su- perintendent and chief nursing officer.

But “about 2.5 lakh nurses graduate every year from diploma and degree programmes, and there are only eight central government hospitals,” points out T Dileep Kumar, president of the Indian Nursing Council. One post at Delhi’s Safdarjung Hospital would get an avalanche of applications, he says.

Many states have made nursing positions contractual because they don’t want to pay pensions and other benefits. This means that often, even nurses in state facilities are only paid Rs 7,000-8,000, says Kumar. Some district hospitals have only one nurse for 20 or 30 patients, he adds. Even in a state like Kerala, a nurse makes only about Rs 700 a day, says Jibin. But even otherwise, govt is a small part of the healthcare sector in India: 70% is in the private sector. “When they join the private sector, doctors’ salaries jump dramatically but nurses’ salaries fall,” says Kannaiyan.

Nursing is a skilled job, and a physically, mentally and emotionally demanding one. But starting salaries at private hospitals are often less than what construction workers or porters might make, say some nurses. Attrition is high, but there’s always a steady supply of young nurses who want to leverage the experience for a job abroad. “Even after spending Rs 6 lakh on a BSc course, we can only expect a maximum salary of Rs 35,000 after years of working. Most of us are doing it only for a short time. The only people who can stay on in nursing jobs in India are those whose husbands have financial security, or who want to stay in a particular place for their families,” says Shrestha. In 2016, the Supreme Court had directed the govt to set up a committee on pay and conditions for nurses in private hospitals. The Jagdish Prasad committee had recommended a salary floor of Rs 20,000 in small hospitals, and parity with the public sector in bigger ones. Pri- vate hospitals have been fighting this order and finding ways around it.

New Norms In Offing

The National Nursing and Midwifery Commission is set to be instituted soon, and will have better norms and coordination, bringing all nursing-related matters under central regulation, says Indian Nursing Council president Kumar.

Investing in nurses can be key to our public health workforce crisis. Nurse-led healthcare has been tried out in the US, Australia and the Netherlands. After advanced training, they take medical decisions and perform procedures, combining clinical expertise with health management and disease prevention skills. Evidence shows it is as effective as physicianled care, and more comforting for patients. India has recently approved a nursepractitioner programme but incorporating it into the healthcare system may take a while and face resistance, says Kumar.

More public investment in the health workforce, and making sure private providers are held to better standards, are the only means to getting Indian nurses to work in India, and for India.

Migration

2010-16

The Times of India, May 09 2016

Sumitra Deb Roy

Nursing brain drain in Maha as emigration hits 5-yr high

At a time when the Indian government has locked horns with doctors over their right to settle in the US permanently , emigration among nurses in Maharashtra has touched a T five-year high in 2015-16. d The last financial year saw a 93% jump in the number of nurses leaving for an international placement when compared to 2010-11.

Statistics collated by the Maharashtra Nursing Council (MNC) that issues NOCs to nurses taking up global placements revealed around 1,567 nurses left the country in 201516, as against 814 five years ago or 920 in 2013-14. It has also emerged that the US and the UK are no longer the most favoured destinations since a significant majority of them took up jobs in Ireland, Aus tralia and New Zealand that offered annual pay packages in the range of Rs 30-50 lakh.

Estimates suggest 25,000 trained nurses across India leave every year for better pay ing jobs.Even the Centre's noti fication of April 2015 banning private agencies from recruit ing nurses for overseas jobs failed to make a significant im pact in Maharashtra. The or der has hit even traditional hubs like Kerala, which saw over a 60% decline in international placements last year.

Maharashtra, too, witnessed a slowdown like Kerala, but not a drastic dip. It managed to register a 2% annual rise in nurses accepting foreign jobs in 2015-16 (1,567) from 2014-15 (1,532), though in previous years the year-onyear increase in international placements ranged from 1770%. “There was a temporary slowdown in recruitments due to the order from the Centre but nurses from Maharashtra still got good offers,“ said Ramling Mali, president of MNC. “The UK has started asking for a higher TOEFL score (English proficiency test) of 7.5 instead of previous 6.5. Many nurses in Maharashtra are finding it difficult to clear the test,“ said Mangala Anchan, registrar of MNC.

Salaries, working conditions

In Delhi, 2019; 2011-19

Rema Nagarajan, Dec 5, 2019 Times of India

From: Rema Nagarajan, Dec 5, 2019 Times of India

Employing an electrician or plumber in Delhi for less than Rs 17,000 a month would be illegal, but most private hospitals and nursing homes in Delhi pay nurses less. Even the biggest hospitals pay less than half of what the Delhi government pays its nurses.

The minimum monthly wage for skilled workers in Delhi is Rs 16,962. The big corporate hospitals barely pay this to entry level nurses while smaller ones pay as little as Rs 12,000-Rs 15,000. The basic salary of a newly recruited nurse in central and Delhi government facilities is now about Rs 45,000 plus house rent, transport and dearness allowances, adding up to anything between Rs 60,000 and Rs 70,000.

An expert committee appointed on Supreme Court direction and headed by the Director General of Health Services recommended in 2016 that hospitals with more than 200 beds should pay nurses the same salary as government hospitals and those with less than 50 beds a minimum of Rs 20,000 for a freshly recruited nurse. In its order, the apex court had said, “We feel that the nurses who are working in private hospitals and nursing homes are not being treated fairly in the matter of their service conditions and pay.” It left it to the committee to look into the specifics.

“Forget the consolidated salary, these hospitals are not ready to match even the basic pay of a government nurse. The high attrition rate in private hospitals, and thus poorly trained nurses and substandard nursing services, is because they refuse to pay decent living wages. That is why most of them also run nursing colleges because student nurses provide cheap labour,” said Rince Joseph, national working president of United Nurses Association (UNA).

Nurses’ unions point out that nurses are not merely skilled labourers but professionals and hence actually ought to be paid more. The BSc nursing degree is a four-year course open only to those who have scored at least 50% in physics, chemistry and biology in Class XII. Diploma courses are for three years and have more relaxed entry criteria.

The Association of Healthcare Providers (India), whose members are 47 big hospitals (100 to 650 beds), including the biggest corporate chains, has filed cases in Delhi high court to prevent the implementation of the expert committee’s recommendations. The association told the court that its members were ready to pay nurses Rs 20,000 per month.

According to UNA, some corporate hospitals, which were paying Rs 16,000 earlier, raised it to Rs 19,800 after Delhi government raised minimum wages a couple of months back. However, they simultaneously raised hostel fees for the nurses, thus negating much of the raise.

After issuing an order in June 2018 seeking implementation of the recommendations within three months, Delhi government has failed to pursue the matter, stated UNA. The AHPI’s repeated attempts to get the Delhi government order stayed have failed as Delhi high court upheld it. “We have tried peaceful protest at Jantar Mantar. Now we have no option but to step up the agitation,” said Joseph.