Dietary-/ Eating-/ Food- habits: India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Deficiencies

2019 – 21 WHO study

Malathy Iyer, Oct 23, 2024: The Times of India

Mumbai : The diet of over three-quarters of India’s children aged between 6-23 months is poor and lacks “diversity” as defined by WHO, new research has found.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), children in the six-to 23-months bracket should have minimum dietary diversity (MDD) and consume five out of the eight recommended food groups. Children who have less than five of these food groups are considered as minimum dietary diversity failures (MDDF).

However, the study, published in National Medical Journal of India a publication of AIIMS also had something to take heart from. “There was a slight improvement in MDDF from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS)-3, when 87% of this age group were MDDF, to 77% as per NFHS-5 conducted in 2019-2021,” said author Gaurav Gunnal from International Institute for Population Sciences, Deonar.

Eight states including Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Gujarat had a high MDDF of over 80%. Only 95 districts in the south, east, and the North-East out of India’s 707 districts had a low prevalence of dietary failure at 60% or lower.

“Dietary failure was higher among kids who were females, from lower socioeconomic groups, did not receive food from anganwadi centres, and were born to younger mothers,” said Gunnal and co-author Dhruvi Bagaria from Indian Institute of Public Health in Gandhinagar.

Dietary diversity helps combat deficiency of micronutrients that play an important role in development and growth. Poor nutrition increases risks of delayed motor and cognitive development, weak learning, low immunity, poor metabolism, memory, and increased susceptibility to infections.

According to NFHS-5, one in every three children is ‘underweight and stunted’, while one in every five children is ‘wasted’ in India.

‘What India eats’

As in 2019

October 12, 2020: The Times of India

From: October 12, 2020: The Times of India

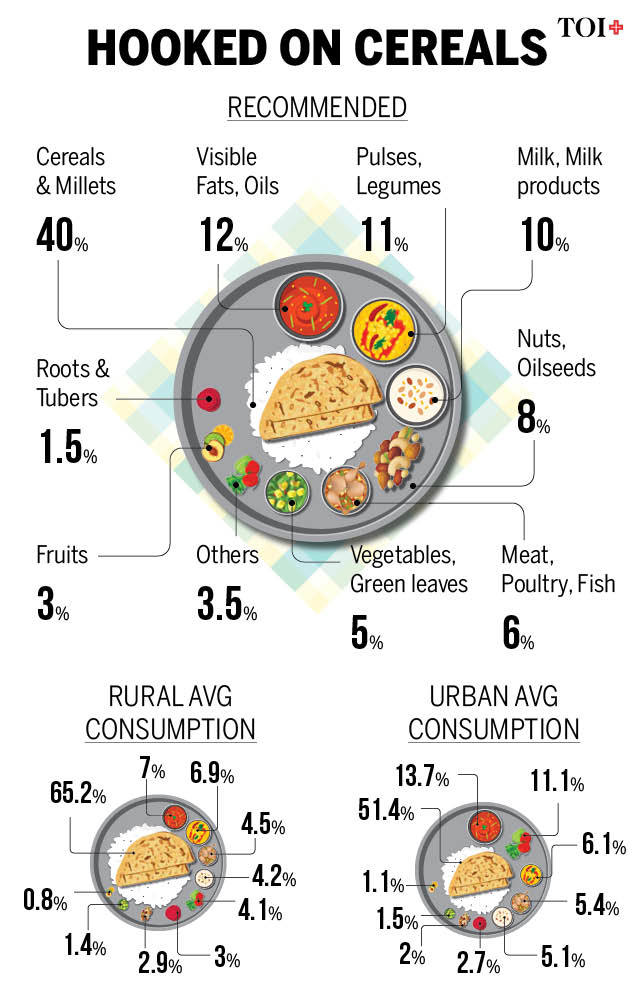

A healthy diet is the first line of defence against disease, but while most find it hard to stick to a balanced diet, nutritional deficiencies are especially stark in India, says a survey by Indian Council of Medical Research-National Institute of Nutrition (ICMR-NIN). Missing out on key foods can lead to diseases like diabetes or heart disease, which are big risk factors for Covid.

ICMR-NIN recommends a 2,000-calorie diet for adults, and the actual intake is 1,943 calories in urban areas across the country and 2,081 calories in the rural areas. But these calorifically adequate diets actually conceal major deficiencies, says the report, which presents the first-ever break-up of the energy Indians derive from different food groups.

DIET AFFECTS HEALTH

The urban North has high obesity and abdominal obesity rates that match its high fat intake. Rural parts of central India, where cereal use far exceeds recommended levels, has the highest prevalence of chronic energy deficiency (CED). While the report says its recommendation does not represent a “therapeutic diet”, consumption of foods at prescribed levels and regular physical activity can boost the immune system and reduce risk of illness.

NORTHEAST TOPS IN CALORIE COUNT

Beyond their over-dependence on cereals, diets across India reflect great variety. Each region relies on certain foods more than the others. Calorie intake also varies by region, from 2,909 calories in the Northeast to 1,723 calories in the urban areas of North India. Data not given for rural consumption in North and Northeast

MORE FAT IN THE NORTH, PROTEIN IN SOUTH, NORTHEAST

Here’s how urban diets look in the different regions of India for the six key food groups that make up more than 80%, or four- fifths, of the recommended daily mix.

Cereals

Average diets in urban North India are the closest to the recommended level for cereals. Urban areas in both the East and NE get close to 60% of their daily energy from cereals

Meat

Pulses and legumes, and meat, poultry and fish are interchangeable in diets and together should make up 17% of total energy intake

Milk

Indian diets crimp on milk and milk products, too, with East and NE most deficient

Pulses

More than 10% of daily energy should come from pulses and legumes, but most diets are lacking in dals and beans. The Northeast is better than the other regions in this respect

Veggies For a country known to love its veggies, their low consumption is surprising. Eastern India fares best among regions

Fats The urban North has the highest fat intake while South has the least

Source: 'What India Eats', report by ICMR-National Institute of Nutrition

What do Indians eat the most

Chandrima Banerjee, May 20, 2022: The Times of India

What do Indians eat the most?

Dal, green vegetables and milk. Across age, gender, economic background, religion, caste — nothing changes this pattern. Nearly half of India has them every day. For every other type of food, more Indians say they have them weekly or occasionally.

This is not surprising. All three are found easily and are relatively more value-for-money than, say, meat.

In 2005, the third NFHS asked both women and men about their food habits for the first time (before that, the second survey had only asked women). When the numbers are compared, the changing preferences are evident.

More people, for instance, have fruits at least once a week now than they did 15 years ago (40% then vs 50% now for women, and 47% then vs 56% now for men). The numbers have not changed for the richest (72-74% both times). How has the jump happened then? It is because the poorest have fruits more often now (27% women and 37% men) than they did in 2005 (16% women and 19% men). The gap is terribly wide but the trajectory is towards a narrower one.

The other big jump has been in the share of people who have milk. In 2015, just 55% of women and 67% of men said they had milk once a week. Now, the shares are up to 72% women and 80% men. Again, while the increase in share has been the highest for the poorest (31% to 53% for women, and 43% to 62% for men), it’s because they had more ground to cover in the first place. But the relatively low consumption of both in economically disadvantaged households has been flagged in the latest survey as “deficiencies in the diet”. So, while there may have been an increase, it is still not enough.

So, who eats non-vegetarian food?

About 85% men and 72% women. In the survey, 17% men and 29% women said they have never had fish, chicken or any other meat. That leaves 83% men and 71% women as non-vegetarians (which the survey report also says). But it does not take into account the share of people who have eggs. Among women, 28% said they have never had eggs (leaving 72% who had) and among men, 15% did (leaving 85% non-vegetarians).

Among both women and men, more Christians have meat regularly than Muslims. If fish is also taken into account, the numbers change but the pattern remains the same. In fact, besides the Jain community, the Sikh community has the lowest share of non-vegetarians by far.

The caste breakup also dispels a myth — of vegetarianism among dominant castes. Because while men (60%) and women (48%) from the Scheduled Caste have the highest share who eat fish, chicken or meat, the dominant caste group is a very very close second (59% men and 47% women).

Among states, the most widespread meat consumption habits are in Kerala for men and Andhra Pradesh for women. For fish, women and men in Goa (both 92%) take the lead. And when it comes to having eggs at least once a week, women (83%) and men (88%) in Andhra Pradesh are at the top.

If the question is widened to ask if people have either fish or meat, then Goa (93% women and 94% men) has the highest share of non-vegetarians.

But overall, just 45% of women have fish or meat once a week while among men, that’s 57%.

What do women eat then?

The same things that men do, but less often. Fruits, for instance. Most women said they have it occasionally. But most men said they have it weekly.

Then, it’s also about how food is perceived. If it’s a discretionary purchase (good to have but not essential), then power dynamics determine who gets access to it. Fried food and aerated beverages are good examples.

Just 16% of women have aerated beverages once a week (among men, it’s 25%). It’s a massive drop since 2005, when 24% of women did. It might seem like a healthy trend but there’s more to it. Because with wealth — 11% of the poorest against 21% of the richest — the share of women who have them goes up. The same goes for fried food.

Does this change when women are pregnant or breastfeeding? A tiny bit for the first and not at all for the second. In fact, fewer breastfeeding women have fruits or milk than women who are neither pregnant nor breastfeeding.

What does all of this translate into? Nutritional deficiency, it seems. Across India, 25% men have anaemia, caused by deficiencies in iron, folate, and vitamins B12 and A. For women, that share is 57%.

(Lead illustration: Sajeev Kumarapuram)