Kumbh, Maha Kumbh, Ardh Kumbh: Allahabad

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

History, evolution

Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

PRAYAGRAJ: Allahabad has a new name, the city also has a new look.

From the railway station to the civil lines, from Arail village to the Sangam area, about 300 murals have brightened the city’s landscape. Even the trees on the Arail road have been painted in bold, barking colours. Kumbh 2019 is less than a fortnight away and Prayagraj already looks like an open-air art gallery.

The murals are largely Hindu mythological in content. Scenes of Samudra Manthan mentioned in the Puranas have been recreated. In times when building a Ram Mandir in Ayodhya is among the hottest political topics of the season, Ram, Sita and Hanuman are well-represented on the city’s walls. One of them, in flaming red and bold yellow, just says “Jai Shri Ram”. Medieval saints such as Kabir and Sankaracharya also find a place. So do scenes from the common pilgrim’s life: women praying at the ghats, for instance. Buildings have been symmetrically painted to create the feel of a temple in some murals.

The painted trees depict a wide variety of animals. Looking at them a child can be taught to spot a penguin, a zebra, a giraffe, and more. Some are just geometric representations. The angry Hanuman is one of the paintings. The initiative is inventive but it does raise the question whether the paint would end up hurting the trees. “Tree-friendly painting material was used to ensure that their health is not damaged,” says Ashish Kumar Goyal, commissioner, Allahabad.

DM (Kumbh Mela) Vijay Kiran Anand says the idea of “Paint My City” was to ensure community participation. “It was meant to conserve heritage and beautify the city as well as highlight Union government campaigns such as Namami Gange,” he says. Among the flagship programmes of the Narendra Modi government, the project had the ambitious objective of reducing pollution of the river and help its rejuvenation. Quite a few murals carry the Namami Gange logo.

The painting of Prayagraj has generally resonated positively in the city. Interior designer Satyendra Pratap Singh is one of those who appreciates the city’s new look. “The religious paintings give a sense of what Allahabad is, a punya bhoomi. The whole city looks like an ashram,” he says. Harishankar Patel, who runs a sweetshop in Arail village, says the street art has transformed his village even though fretful pigs run amok on a garbage heap next door.

Several organisations, such as Delhi Street Art, took part in the project. “About 100 painters with street art experience from my team alone were involved in the job from October to December. Five of them came from foreign countries such as the UK, Russia and US,” says Yogesh Saini, founder, Delhi Street Art.

However, social scientist Badri Narayan bemoans the lack of representation given to all communities in the murals. “Allahabad was also a seat of Sufi knowledge but that aspect of the city doesn’t find any representation. It would have been nice if poets like Akbar Allahabadi and Firaq Gorakhpuri (real name: Raghupati Sahay) were given space,” says Narayan, director, Gobind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute. Renowned litterateur Harivansh Rai Bachchan is among those who does.

Novelist Neelum Saran Gour points out that the city has three co-existing and interlinked narratives: Indic, Islamicate and European. “However, the walls and the trees show only one of the three. The freedom struggle, to which Allahabad was central and integral, is missing,” she says.

From Harshvardhan’s Magh mela to the Raj-era Kumbh

Avijit Ghosh, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

Academic and author Neelum Saran Gour was born and bred in Allahabad. One of her works is about the culture and history of the city. A professor of English at the University of Allahabad, she speaks with Avijit Ghosh on her memories of the Kumbh mela, the rising politicisation of the festival and the changes it has brought to her city:

What are your memories of the Kumbh mela?

For me as a teenager, Kumbh meant waking up in the winter cold to the sound of endless footsteps. These were thousands of pilgrims coming in from surrounding villages and walking by our home. I was not deeply into the religious side of Kumbh. My husband’s family used to do the kalpawas. You stay by the Sangam for a month and observe certain rules of restraint. They used to rent a tent and carry the entire kitchen with them. Even the dog used to be there. It was something like a picnic.

The Kumbh was something for the city to enjoy. It was religious no doubt. But it was quietly religious. It was dignified and serene; a quiet, spacious and easy affair. Kalpawas was a private choice. Kumbh did not impact the consciousness of the people. The infrastructure of the city remained untouched by the festival. The Kumbh area had tents and lights. But it was all very simple compared to the present.

What’s different now?

In our childhood days, the Kumbh wasn’t an event trumpeting in your eardrums. In 2013, we couldn’t go to the Sangam due to traffic congestions and the detours. It was impossible for the ordinary citizen to visit the festival without getting utterly exhausted. In 1977, we had walked across the Kumbh nagri. We were younger then, but it was also easier to do so. Due to the growing scale, locals like us find it difficult to visit now. We managed to visit the area even during the Ardh Kumbh in 2007. But in 2013, we just could not go. We went when it was all over.

I sensed the political noise for the first time in 2013. The big hoardings talking about Hinduism being in danger. It was the Hindutva forces, the VHP. There was something different and combative in the air. We bought a trident at Kumbh in the 1980s. Today the trident has become a symbol of aggression. It wasn’t before. I like the idea of trident. The yogi plants it before himself when he meditates alone in the wilds of the mountains with the fire burning. It is a symbol separating the life of the saintly solitude from the chaos of the ordinary world. I never looked upon it as a weapon of militancy. Which is why I have never taken it off the wall.

The Kumbh was never called the Kumbh. The whole idea of Kumbh was constructed during the British period by the Prayagwals, the pandas on the banks of the river. Earlier, it was called the Magh mela and King Harshvardhan started it. Although the Magh mela, as attested by Chinese travellers, was a multi-religious conclave for Buddhists, Shaivites and sun worshippers who received generous endowments from Harshvardhan, it also witnessed scenes of sectarian clash and conflict.

Is Kumbh 2019 about making a political statement?

Yes, it is a power spectacle. And I do think that it has something to do with the 2019 election. The festival draws practising Hindus from all over India. It is very convenient to bring them all together at one site. I often think that it is using religion for extra-religious ends. The vast multitude comes for their own purpose. At the same time, if these signals are being thrown from all sides, there may be some impact. If it is there in every hoarding, in every pravachan, there could be an accumulative impact.

The Kumbh preparation has recast Allahabad as a city. What is your take?

The roads have been broadened. It is very good news for a city that is filling up with more and more vehicles every year. But we are not happy about so many trees being felled. Maybe new plantations will replace the lost trees. And one doesn’t know the kind of material being used when there’s a haste to finish projects. So much of historical value has been damaged. A Mughal doorway near Khusro Bagh which had great historic value has been pulled down. That could have been avoided.

In other countries, people are so mindful about heritage. Here there has been a domineering disregard for that. However, I am happy to see the new roads. The illegal encroachments deserved to be pulled down. In all fairness, I am happy to see the different shape being given to the city. I am optimistic that we will find a better city at the end of it.

Missing persons

2019: 1,000 lost pilgrims a day

Sitting in a corner of the ‘Bhoole Bhatke Shivir’, 72-year-old Vindhyawati’s eyes scan the entrance to the tent every few minutes. The resident of Satna in Madhya Pradesh had been looking forward to her pilgrimage to the Kumbh Mela for years, but on that day, February 8, she was separated from her family among the millions assembled on the Ganga’s banks for the largest such gathering in the world.

‘Separated and lost at the Kumbh Mela’ is a recurring, much-referenced and even fond trope of Indian popular culture, including Hindi movies, which in the 1970s used to have entire plots revolving around it. But for pilgrims who actually get lost in the thronging crowds, ranging from the very young to the old and infirm, it is a traumatic experience. The people who man the Bhoole Bhatke Shivir now have technology to help them re-unite families.

A pilgrim was kind enough to bring Vindhyawati to the tent. In a state of shock, the old woman had hardly spoken to anyone at the camp as she kept looking for her kin for two whole days, worried that she might never see them again.

On Sunday that she heaved a sigh of relief when she saw her family members’ faces on a smartphone screen via a video call after a volunteer traced their contact number. Later during the day, a police team accompanied Vindhyawati to Satna.

Camps like Bhoole Bhatke Shivir are run using carefully-maintained manual records, but computerization is also helping. At computerized centres, volunteers keep updating details of lost people, which are then displayed prominently on screens across.

The task is massive: by February 10, the day of the third and last Shahi Snan of Kumbh 2019, volunteers managed to reunite over 24,000 people with their families, according to senior superintendent of police (Kumbh) KP Singh. By then, 14 crore pilgrims had taken part in the holy dip at the Ganga from the day the Mela began on January 15. Which means on any average day, more than 1,000 pilgrims go missing or are separated from their groups.

“We have set up 15 special police teams to take lost persons back to their native states if their fellow pilgrims have already left. This time, we sent 72 people back home. We traced their families after compiling information through various means including biometric details,” SSP Singh said.

Computerized lost-and-found camps was first introduced during the 2013 Mahakumbh, while the traditional camps have been operational since 1946.

In the 2013 Mahakumbh alone over 42,000 lost people were reunited with their families, while the Mela saw 16 crore pilgrims participating. In the 2007 Ardh Kumbh, over 23,000 people were similarly reunited.

Organiser of Bhoole Bhatke Shivir, Umesh Tiwari said, “Once inside our camps, volunteers offer lost pilgrims food and blankets.It could take days to find their families.”

Murals

2018

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 4, 2019: The Times of India

See pictures:

Streets come alive with art in Prayagraj .jpg|Streets come alive with art in Prayagraj

A priest outside a temple at Ram ghat.jpg|A priest outside a temple at Ram ghat

Hanuman adorns a wall.jpg|Hanuman adorns a wall

Trees never looked as colourful...

4 major art spots in Prayagraj

Sculpted figures being put up to create a mythological theme for Kumbh

Gods watch over all...

High-rises too get a splash of colour

Flyovers get a makeover in vibrant colours

Gods watch over all...

Art, life and spirituality converge at Kumbh

2018

Administration

Vegetarian, teetotaller, non-smoking policemen wanted: 2018

Wanted: Men — young, energetic, vegetarian, teetotaller, non-smoker and soft-spoken. This is no matrimonial advertisement, but the qualities the Kumbh Mela administration is looking for in policemen to be deployed during the Mela in Allahabad, starting January 15, 2019.

This apart, the policemen should also have “certified good character” clearances from their seniors. The department has also decided no police official on duty during the Kumbh should belong to Allahabad.

Deployment of security will start by October. More than 10,000 men in uniform, including paramilitary personnel, are expected to be on duty during the Kumbh.

An age limit has been set for various ranks — constables to be assigned duties should be below age 35, head constables below 40 and subinspectors and inspectors below 45 years.

DIG/SSP (Kumbh) K P Singh, said, “We’ve written to the SSPs of Bareilly, Badaun, Shahjahanpur and Pilibhit to verify the character of policemen who have applied for the Mela duty as the department seeks only vegetarian, non-smoking, non-drinking and soft-spoken policemen for the period.”

Starting October 10, police will be assigned duties in four phases. Around 10% will be deployed in the first phase, Singh said, and 40% in the second phase in November. In phases three and four, 25% of paramilitary forces will be deployed in December.

The DIG added that he has written to SSPs to interview policemen personally as officials for the second, third and fourth phases will be coming from western and other parts of the state.

2019

Administrative arrangements

Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 5, 2019: The Times of India

Area and number of visitors

From: Avijit Ghosh and Anindya Chattopadhyay, January 5, 2019: The Times of India

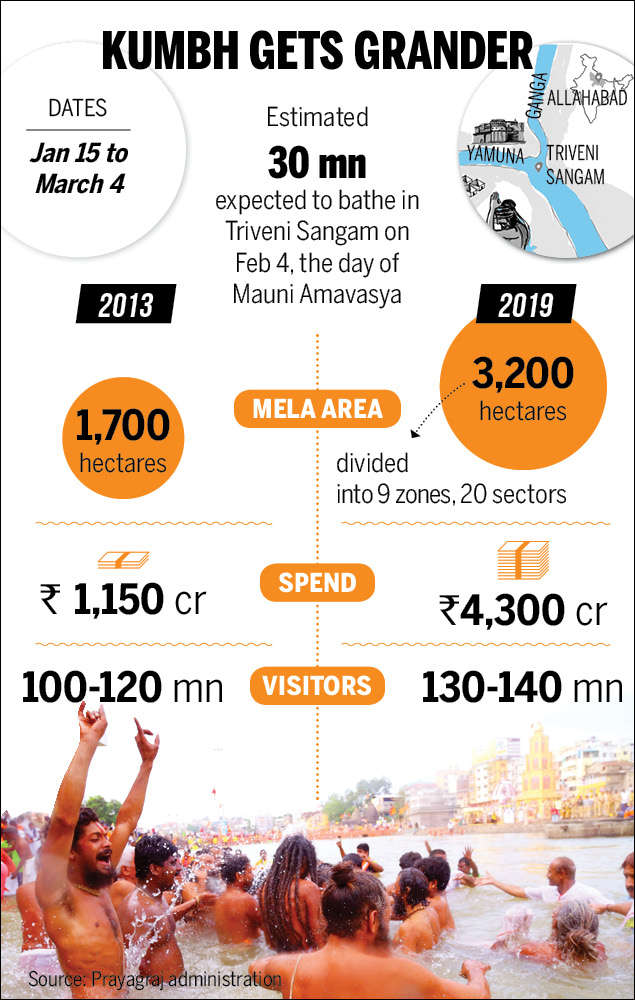

From January 15 to March 4, an estimated 130-140 million pilgrims and tourists are expected to do the same during the Kumbh Mela. For the devout, a holy dip will rid them of their sins, free them from the cycle of life and death. The term Kumbh is contested. Some insist that the 2019 event is Ardh Kumbh, in accordance with the traditional alternating cycle of Kumbh and Ardh Kumbh every six years. But last year Yogi Adityanath’s Uttar Pradesh government rechristened Ardh Kumbh as Kumbh. Kumbh, henceforth, will officially be known as Mahakumbh. Interestingly, Modi described the event as “Ardh Kumbh” in a December 16 speech in the city.

Renaming is the flavour of the season; till last month, Allahabad was the town’s official name. The renaming, especially of the festival, is argued even at the Sangam ghat.

But there’s unanimity that the scale of arrangements is unprecedented. In 2013, the mela was spread over 1,700 hectares; this time it is 3,200. The budget for Kumbh 2019 is Rs 4,300 crore; as per reports, it was about a third in 2013. “ Jo na 2001 mein hua, na 2013 mein hua, aisi vyavastha dekhne ko mil rahi hai (The arrangement is more than 2001 or 2013),” says boatman Ramesh Nishad, referring to the street lights and toilets in the area.

The arrangements were still a work in progress, though. Last Sunday, tractors purposefully carried tons of black sand at Sangam. And one saw hundreds of commodes waiting to be fitted in the mela area.

For the government, sanitation seems to be a key area. Dozens of health department workers in maroon jackets keenly collect any piece of paper or plastic lying about. “In all, 1,22,500 toilets, including 20,000 septic tank toilets, are being laid out,” says AP Paliwal, additional director for health and sanitation (mela).” He talks about an elaborate mechanised system of compactors and tippers for solid waste management. “We don’t want a single drop of sewage to pollute the river.” A special medical unit to track and avert possible break-outs of epidemics has been set up.

Using drones for surveillance, carrying out mock anti-terror drills and setting up an integrated command and control centre with 1,100 cameras for real-time feed — the BJP government seems keen to project Kumbh as a safe and efficiently-managed, high-tech event. Digital screens across the city show films on Kumbh day and night. On social media — Facebook, Twitter and Instagram — the campaign is relentless. The returns, though, are modest. The official Kumbh handle has 8,500 followers while Facebook’s official Kumbh page has 37,000 likes.

Social scientist Archana Singh says the administration has taken a techonological leap in providing traffic information on Google maps and signage in satellite town parking and mobile app, to facilitate pilgrims. “But to enjoy these facilities you need a smartphone. They seem to have overlooked the fact that an overwhelming majority of pilgrims come from rural, technology-challenged backgrounds,” she says.

Singh’s team provides inputs to the local police to improve its efficiency. Arranging e-rickshaws for the physically challenged and having volunteers who speak different languages and dialects to assist the police are among the suggestions provided by them. “We have also organised workshops for police with special emphasis on gender sensitisation,” Singh says.

Outside the mela area, the rest of the city is also getting ready for Kumbh. Broken pavements have either been or are being repaired and upgraded. Road dividers are bringing order to traffic. “Nine railway overbridges have been constructed in and around the city. Six underbridges have been widened,” says Ashish Kumar Goyal, commissioner, Allahabad. He adds, “More than half of the Kumbh budget is for the city’s permanent works.”

For a city that seemed to have regressed with time, infrastructure projects have been fast-tracked due to the Kumbh. “Earlier, Allahabad had an airstrip. Now it has a full-fledged terminal,” Goyal says. PM Modi inaugurated the new terminal last month. SpiceJet will begin a daily flight from Delhi on January 6.

Illegal encroachments, some several decades old, have been removed. Trees, even older, have been felled. About 300 murals have transformed the city into a flamboyant open-air art gallery even though there’s near-amnesia on the city’s Mughal and British past.

There is a flip side to the city’s recasting. Dust hangs over Prayagraj like a thin film of brown smoke. “You would have never seen so many people wearing pollution masks in Allahabad as today,” says Singh.

Social scientist Badri Narayan says there was a need to distinguish between the well-heeled encroacher who expanded his house illegally from the urban poor: the tea sellers, the hawkers. “The administration could have been more sympathetic towards them. Development must have a human face,” says Narayan, who’s the director of Gobind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute.

But Goyal has a different take. He says that even places of worship were shifted by taking locals into confidence. “We have got tremendous public support for removal of encroachments,” he says. Novelist Neelum Saran Gour points out that a Mughal doorway near Khusro Bagh was pulled down. “That could have been avoided,” she says. But adds, “I am optimistic that we will find a better city at the end of it.”

Kumbh is boom time for many small traders and hawkers. The city’s 600-odd boatmen are also expecting a major jump in their income. Boatman Rishi Nishad said: “On an average we earn Rs 300 to Rs 800 per day. During Kumbh, we are expecting to at least triple our income. Not only because of the number of visitors, but also rates will double due to high demand.” Priest Dinesh Pandey also expects a similar raise in his earnings during the seven-week festival.

Many small hawkers are worried, though, that they won’t be able to set up their stalls. Sunil Kumar, who peddles cheap hosiery for a living, says his shop was shifted two km away. He is worried that he might be forced to shift again. “ Chhoti pheriwalon ko bahut pareshaniyan hai (There are lots of problems for small hawkers),” he says.

Not all problems have been resolved yet. But the UP government is working overtime to make the holy festival a success. “We are in the process of applying for three Guinness records in the areas of cleanliness and transport and for the ‘Paint My City’ campaign,” says Goyal.

For most pilgrims, however, the Kumbh has one simple meaning. As a couplet on one of the banners says, “ Anya teerthon mein gyaan, aur Prayag mein moksha ka snan (In other holy places you get knowledge / In Prayag, you get the bath of salvation).

The three shahi snans and Mahashivaratri

The 49-day Kumbh mela drew to a close at the Sangam notching up three world records in the Guinness Book and a footfall of 24 crore people. On Monday, over 1crore faithful took the holy dip on Mahashivaratri, the last of the ‘snans’ that started on January 15.

The Prayagraj Mela Authority secured three world records: over 7,600 people came together to create the world’s fastest handprint painting in eight hours, it mobilized 10,000 individuals to sweep multiple venues at five locations in a single day, and paraded the largest number of buses in the world, a fleet of 503 running a length of 3.2km.

Officials said around 45% of devotees took a dip at the three shahi snans — 2.25 crore at Makar Sankranti on January 15, more than 5.5 crore at Mauni Amavasya on February 4 and 2 crore on Basant Panchami on February 10.

UP minister of state (independent charge) Suresh Kumar Rana said, “The Kumbh Mela hosted delegates from 192 countries.”

An Italian national at the Kumbh, Alasendaro, said, “The atmosphere is rustic yet replete with spirituality and energy. It’s a great experience and can be felt only through physical experience.”

The Kumbh will be officially declared closed on Tuesday by UP CM Yogi Adityanath.