Lucknow: P-R

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

This article was written in 1939 and has been extracted from

HISTORIC LUCKNOW

By SIDNEY HAY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ENVER AHMED

With an Introduction by

THE RIGHT HON. LORD HAILEY,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E.

Sometime Governor of the United Provinces

Asian Educational Services, 1939.

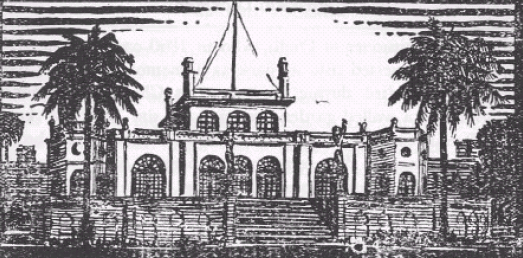

Qadam Rasul

In The Horticultural Gardens opposite the Carlton Hotel stands a small domed building upon a high artificial mound, known as the Qadam Rasul. Qadam means a step. It was erected during the reign of Nasir-ud- Din Haider, between 1827 and 1837, to house a sacred relic, an impress of the Prophet’s foot in stone brought by a pilgrim from Arabia.

During the Mutiny the relic was removed, and the native forces, wishing to outwit the British, used the Qadam Rasul as a powder magazine. The besieged force incurred heavy losses from snipers stationed in mosques overlooking the Residency, which mosques the engineers wished to destroy. Sir Henry Lawrence was adamant in his reply: “Spare the holy places, and private property, too, as much as possible.”

The mutineers knew the respect that the British had for religious places and trusted in this to keep intact their powder magazine. During the second relief, the fierce battle of the Sikandar Bagh was fought on November 16. After a short rest the relieving force advanced towards the Residency, but they had only gone about four hundred yards when they met with resistance from the Qadam Rasul. Standing on a mound, it looked formidable, but the nerve of its handful of defenders had been badly shaken by the fate of their comrades at the Sikandar Bagh, and the position was easily taken by the 2nd Punjab Infantry, part of Greathead’s brigade.

Early the next year many posts had to be retaken. On March 11, Medley and Lang, two engineers, went on a personal reconnaissance. They found the Qadam Rasul and the Shah Najaf empty, so they called up their men and ordered them to throw up defences and earthworks so that when Sir E. Lugard advanced he was able to seize them both without opposition.

The building has been condemned, as unsafe, but a flight of steps leads to the top which affords an unexpectedly good view of the Khurshaed Munzil. It is still possible to make one’s way round the outside of the cracked and crumbling dome.

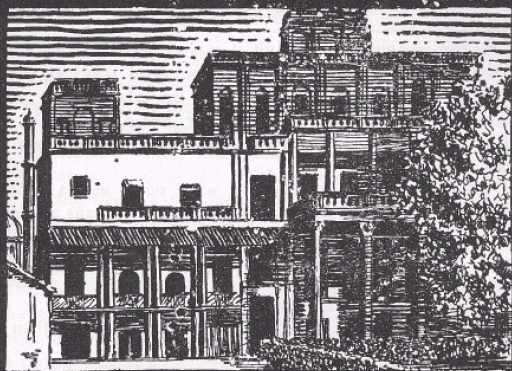

Roshan-Ud-Doulah Kothi

The Roshan-Uddoulah Kothi lies behind the Kaiser Bagh quadrangle. Approaching from Hazratganj, turn into the road leading down the centre of the Kaiser Bagh, go beneath the centre gateway on the right and turn immediately to the left. The Roshan-ud-Doulah confronts you.

Roshan-ud-Doulah who built it was minister to King Nasir-ud-Din Haider after the dismissal of the great reformer Hakim Mehdi in August, 1832. At that time the salary of the prime minister was Rs. 25,000 a month. Over and above this he took five per cent of the revenue, which made his picking about six lakhs a year.

Roshan-ud-Doulah possessed a wily mind and a smooth tongue. He resented the power wielded by Europeans at Court.

One day he suggested to the King that they showed lack of respect when they entered the royal presence without removing their shoes, hoping by this means to bring them into disfavour. The King was equal to him.

“Roshan-ud-Doulah,” said he, “am I a greater man than the King of England ?” “It is not for your majesty’s servant to say that anyone is greater than his lord.” “Listen to me, Nawab, and you, General, listen to me. The King of England is my master and these gentlemen would go into his presence with their shoes on. Shall they not come into mine, then ? Do they come before me with their hats on ? Answer me, Your Excellency.” “They do not, Your Majesty.”

“No, that is their way of showing respect. They take off their hats, and you take off your shoes. But, come now, let us have a bargain. Wallah, but I will get them to take off their shoes and leave them without, as you do, if you will take off your turban and leave it without, as they do.”

The Nawab said never another word. The King and his minister would disguise themselves in European clothes and wander about the bazaars, listening to the general conversations after the manner of the caliphs of ancient Baghdad.

Some years later the Roshan-ud-Doulah Kothi was turned into Government offices, which function it still fills. The lofty centre chamber is filled with clerks sitting cross-legged at their little sloping desks a few inches high. Through many rooms and up a narrow winding stair is a flat roof. There perches a little iron statue of a famous dacoit, which was slightly injured by the earthquake of 1933.

This dacoit performed many deeds of daring. So cunning was he that the authorities could never catch him. One day he sent a message to say that he would visit the Roshan-ud-Doulah Kothi on a certain date at a certain time. Many were the preparations and traps set to catch him, but he evaded them and paid his call in safety. He was never caught to the day of his death, and to his memory this iron statue was erected.

Roshan-ud-Doulah also built the Qaiser Pasand which occupies a similar position to the Roshan-ud-Doulah Kothi on the opposite side of the Kaiser Bagh. After the death of Nasir-ud-Din Haider Wajid Ali Shah confiscated it and gave it to his favourite concubine, Mashuq-us-Sultan.

In 1857, some of the refugees from Sitapur were captured and confined to the lower rooms of the Qaiser Pasand, where they were comparatively well treated until their captors were repulsed from an attack upon the Alam Bagh. On September 24, they were dragged out and murdered in a nullah not far from the gate of the Chini Bazaar upon Neill Road, where a memorial has since been raised.

Somewhere between the Roshan-ud-Doulah and the Qaiser Pasand a giant mulberry tree spread its shade over a marble platform.

Once a year the Kaiser Bagh was thrown open to the public for a great fair. The trunk of the mulberry tree was then painted a vivid scarlet. Upon the marble platform sat King Wajid Ali Shah dressed in the saffron robes of a fakir, while his subjects streamed past him. Besides the more humble pleasure seekers, “mounted cavaliers in rich clothes, embroidered with gold, preceded by attendants carrying gold and silver sticks, swords, spears and wands of office passed to and fro in a continuous stream. Dignitaries seated in open palanquins richly painted and gilded, mingled with the throng, followed by armed retainers and mounted escort, others reclined gracefully in curved howdahs, some of which were of silver, upon the backs of elephants.

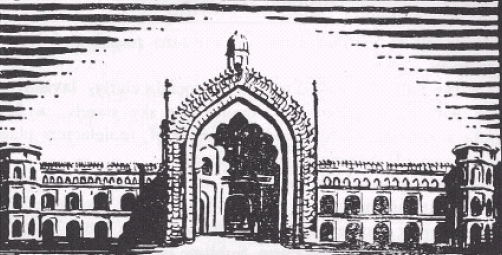

The Rumi Darwaza

Beyond The Great Imambara and at right angles to it stands the Rumi Darwaza, or Turkish Gate which turns its finest architectural face to Husainabad. From the Great Imambara it is seen as a massive structure with a tiny aperture in the base to admit the traffic. The best view is obtaind by driving about a hundred yards beyond, until a road leads left to Victoria Park. There turn round and look at the gateway.

It is the half of a vast dome cut perpendicularly, lavishly encrusted with ornamentations. Against the sky stands a frieze of knobs suggesting, so it is said, the heads of malefactors placed there by way of warning to their friends.

The gateway was built in 1784 at the same time as the Great Imambara at the instance of Asaf-ud-Doulah. It was relief work during the great famine which lasted from 1784 to 1786. Tradition says that it is a copy of the Porte Sublime in Istambul. No gateway of like design exists there to-day although there may have been one before 1453, when Muhammad II conquered the city. Gate and Imambara harmonise with each other.

Just beyond the Rumi Darwaza a low white wall surrounds rising ground shaded by trees. In this peaceful spot lie buried those who dwelt and died in the Machhi Bhawan when it had been rebuilt after its destruction in 1857. It was the fashion at that period to indulge in flights of poetic fancy, though the final results do not always inspire the emotion intended by the author.

Over the remains of Sergeant Lawrence Byrne, his loving wife states in jaunty measure— “Passing stranger call it not A place of dreary gloom. I love to linger near the spot It is my husband’s tomb.”

—which cannot surely have been quite the impression she intended to convey. Another occupant of a tomb, Gunner Martin, complacently says in the course of a lengthy verse—

“I know you felt it hard to part With me the darling of your heart.” They are not all in this strain. One pathetic stone was raised by the parents of four children, three of whom died at the age of two and a half, while the fourth struggled on only to die when she was eight.

Opposite the gate of this little graveyard a road runs down one side of the Husainabad Garden. A little way beyond this, on the left hand side, is another tiny cemetery, badly overgrown and in a sorry state of disrepair. In it are ten tombstones, several unlettered, but probably belonging to a Mission. One name is striking—that of Mr. J. Fieldbrave.

It has been suggested that this may possibly have been the name given to an Indian Christian as a reward for an act of gallantry performed during the Mutiny. Records of the American Methodist Episcopal Mission show that a branch was established in Husainabad in the winter of 1858, the two missionaries living in the Asafi and Kala Kothis until 1866. This must have been their ultimate resting place, for one stone records the death of Eldore Noyes Messmore who died in 1869 aged five.

The Rev. J. Messmore, who was a missionary in Lucknow for many years, erected the English Church in Lal Bagh.

After 1866 the Mission moved to Lal Bagh and Inayat Bagh ; for, when the ground surrounding the Machhi Bhawan was cleared, the local population naturally decreased. The Victoria Park near here is one of the many “lungs” where Lucknow prides herself that her citizens may breathe air less congested than that of the narrow and tortuous streets of the city.

Green lawns shaded by fine trees now undulate in all innocence where once broken ground and narrow alleys and courts concealed dark crimes and their perpetrators. Here thief met thief to plan assault upon rich and unsuspecting citizens. Here they met again to compare notes and to argue through the night upon division of the loot. In 1890 the trustees of the wealthy Husainabad Endowment Fund took over the ground to convert it into a park. There now stands a bronze statue of Queen Victoria erected in her Jubilee year.

Beyond the park lies the Chowk entered by the Gol Darwaza which once bore great elephants upon either flank. Asaf-ud-Doulah built the Chowk at the end of the 18th century. This is a typical Indian bazaar street, furrowed and rutted, the houses unbelievably narrow and rising to a height out of all proportion to the width. Here jewellers and silver filigree workers ply their trade; pearl merchants unwrap from tiny scraps of rag dozens, nay hundreds, of fine pearls and the finest of soft silks set off with golden embroidery.

Through the ages an Indian bazaar never changes. It is, as it always has been, simply a collection of shops, generally in a narrow street, and for the most part containing similar articles. It is a lane full of small shops, with open fronts, where its men expose their wares and invite the passers-by to try them. The shops appear small from the confined frontage. Yet enter one of them and you discover room after room filled with merchandise. You go upstairs and downstairs to the right hand and to the left, and find nothing but goods, save a salesman who is ready to take his oath on “Ganga ka pani” that the worst article in his shop is the best of its kind.