Lucknow: S-U

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

This article was written in 1939 and has been extracted from

HISTORIC LUCKNOW

By SIDNEY HAY

ILLUSTRATED BY

ENVER AHMED

With an Introduction by

THE RIGHT HON. LORD HAILEY,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E.

Sometime Governor of the United Provinces

Asian Educational Services, 1939.

The Sher Darwaza

On The Road Leading From Sa’adat Ali Khan’s tomb to the gardens crowned with the white marble statue of Queen Victoria stands an unpretentious gateway once known as the Sher Darwaza or Tiger Gateway. About a hundred years ago it gave on to a courtyard. A labyrinth of tiny streets and alleys wove around the rickety houses ; crazy steps led to pools of stagnant water. Dirt and disease lurked in every corner. Near the gateway stood a building dedicated to the twelve Imams, the descendants of Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet.

When the British Raj assumed control of Oudh, this net-work of dwellings was swept away leaving only the Sher Darwaza., its name changed by violent circumstances into Neill’s Gateway.

Brigadier-General J. G. S. Neill, C.B., A.D.C. to the Queen, belonged to the 1st Madras Fusiliers. The year 1857 found him with his “Lambs” sent from Calcutta to deal with the recalcitrant inhabitants of Benares, Allahabad and Cawnpore. He finally arrived in Lucknow with the first relief column.

At half past eight on the morning of September 25, 1857, the advance sounded, and Neill’s Brigade, headed by Maude’s Battery and two companies of the 5th Fusiliers, led the column and moved off from the Alam Bagh towards the Yellow House. At Char Bagh they were checked by the canal the bridge over which was strongly held by the rebels. In the confined streets there was only room for two of Maude’s guns to come into action and the gunners suffered heavily under fierce fire. Maude and his subaltern, Maitland, both took active part in firing the guns.

Young Havelock, son of the General and A.D.C. to his father, was standing nearby when Maude called out that he could not hold out much longer. Young Havelock rode over to General Neill with the message, but the General refused to attack without authority, saying, “General Outram must turn up soon.”

The story goes that the son wheeled his horse and galloped in the direction where his father was supposed to be. In a few suspiciously short minutes, he returned, bringing a verbal “message” that General Neill was to carry the bridge at once. Another version says that Colonel Fraser Tytler, D.A.Q.M.G. of the column, persuaded Neill to attack. In any case, the 1st Madras Fusiliers were ordered to assault.

Lieutenant W. D. Arnold dashed on to the bridge closely followed by his own men and a few of the 84th. Tytler and Lieutenant Havelock also galloped up but Tytler’s horse was killed under him. Havelock escaped unscathed although he stood dismounted in the middle of the bridge waving his sword and encouraging his men. Arnold was shot in both thighs, but was made happy in the knowledge that the charge led by him carried the bridge and assured the success of the day.

On Septmber 27, Mr. Thornhill of the Bengal Civil Service, who had been in the Residency all through the siege, volunteered to go and bring in the wounded. He had previously been Assistant Commissioner of Lucknow and knew his way about. Somehow, having collected as many of the wounded as he could he lost his way back to the Residency and by mistake guided the long chain of doolis, filled with helpless wounded men, into the square near the Sher Darwaza. Here they were set upon, many being murdered.

The insurgents set fire to the doolies so that many poor sufferers were burned to death. Directly Mr. Thornhill had realised his mistake he rushed back to stop the rear of the column from entering the square, but as he ran he was wounded for the third time during the siege in the arm and eye. He died on October 12. Lieutenant Arnold, wounded on the Char Bagh Bridge, was lying in one of the carried into Doolie Square, and although he escaped massacre, he died a few days later. Two private soldiers, Ryan and McManus, made heroic efforts to save him, both being awarded the V C. Lieutenant Arnold is believed to have been the son of the famous Dr. Arnold, Headmaster of Rugby.

The next day the site was again the scene of fierce fighting. As the evening wore on, from the top of the Sher Darwaza a shot was fired which mortally wounded General Neill. At the place where he fell stands a small monument inscribed “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori”, with the name of Neill and the manner of his death.

At Ayr where his family trace their descent from the 16th century, a memorial describes him as “a brave, resolute, self-reliant soldier, universally acknowledged as the first who stemmed the torrent of rebellion in Bengal. Over his remains a memorial has been erected in the Residency cemetery to the officers and men of the 1st Madras Fusiliers who fell with him in Lucknow.

Further along Neill’s Road, nearly opposite the Kothi Nur Bakhsh, stands a memorial inscribed with several names.

On June 3, 1857, the 41st Native Infantry mutinied at Sitapur and killed Colonel Birch their commanding officer and other officers, before making off to Fatehgarh. The other regiments in Sitapur immediately followed suit. The Europeans who remained made the best of their way across the river. Fourteen men, women and children reached Lucknow on June 8 and 10, but others who took refuge with Raja Lone Singh at Mitauli were turned out by him on August 6, and wandered about evading capture in the jungles until the end of October, when some three hundred of the Raja’s troops arrested them.

Sir Mountstuart Jackson, aged nineteen, Assistant Commissioner of Sitapur, Captain Patrick Orr and Lieutenant Burnes were loaded with irons. They and the women and children with them, including one of Sir Mountstuart’s two sisters, who had only lately arrived in India, were taken to Lucknow. There they were imprisoned in a tiny hovel within the Kaiser Bagh. On November 16 the men were taken away and shot by some of the deserters from the 71st Regiment.

Mrs. Harris, in her diary of the siege written within the Residency, says on June 27: “Eleven persons, ladies and gentlemen, escaped from Seetapore and are hiding in the jungles protected by a Rajah who is very civil to them, and the two Miss Jacksons and their brother are among them. It was positively asserted that they had been killed at Seetapore, the natives declaring they had seen their bodies, which leads one to hope that others may be found alive some day.”

In 1858 Mrs. Harris added a postscript: ‘Only one of the Miss Jacksons escaped with her brother: the other was taken by a Rajah and has never been since heard of. Sir M. Jackson and his poor sister are still prisoners in Lucknow.”

The Sikandar Bagh

The Sikandar Bagh Is one of the more modern of Lucknow’s historic remains. It was built by Wajid Ali Shah, the last King of Oudh, for his favourite wife Sikandar Mahal Begum.

In the days of its original glories, the Sikandar Bagh was laid out with gaily coloured flower beds, grouped round a pillared baradari, the whole enclosed by a stout wall which still stands save where a road has been driven through.

The three-storeyed entrance gate is in moderately good repair and bears two excellent specimens of the royal fish badge. Under some of the more sheltered archways, traces of richly coloured and finely executed stucco still hint at past glories.

The troops who undertook the first relief of Lucknow under Havelock came within sound of the gun on September 22 and two days later halted to rest after several sharp encounters, while Outram and Havelock discussed the arrangement for further advance. Finally Havelock decided to cross the canal at Char Bagh and to approach the Residency by way of the Sikandar Bagh and the Chatter Munzil. He ultimately accomplished this on September 25, to find that his relieving force was strong enough only to reinforce the besieged ; not to rescue them.

The second relief under Sir Colin Campbell moved off from the Martinière at 8 o’clock on the morning of November 16. They followed the course of the Gumti until they turned up a narrow lane leading to the Sikandar Bagh. Suddenly a murderous fire came from the Sikandar Bagh walls ; for a short time Campbell’s troops were scarcely able to move from the congested space in which they found themselves.

Presently the only company of the 53rd with the column took cover and returned the enemy fire, while Blunt’s horse battery somehow struggled up the steep banks of the lane and galloped into the open. The opposing fire showed no signs of slackening. One bullet which passed through a gunner and killed him, went on to strike Sir Colin in the thigh.

For an hour the troops bombarded the Sikandar Bagh, solid walls stoutly resisting bullets, until a small breach, about three feet square and nearly four feet from the ground, was discerned near one of the corner bastions. Sir Colin ordered the advance. No sooner had the bugle sounded than the 4th Punjab Infantry, the 93rd Highlanders, and the 53rd charged forward in a glorious race to be first through the breach.

It is a moot and much discussed point who actually was first, but it seems generally accepted that Captain Burroughs of the 93rd has good claim to the title. He is said to have jumped clear through the hole, followed by a Sikh of the 4th Punjab Infantry. Highlander and Sikh pressed forward, Lieutenant Cooper, Colonel Ewart, and Lieutenant Gordon Alexander, all of the 93rd, being well to the fore, while the main body of the attackers made for the entrance gates where some of the defenders were holding an earth-work.

The garrison rushed to shut the massive doors, but Mukarrab Khan, a sepoy of the 4th Punjab Infantry, thrust his left arm into the aperture. It was badly wounded, so he thrust his other arm into the space instead, only to have that too almost severed at the wrist. The delay allowed his comrades to collect in sufficient numbers to force the doors. But for his unhesitating bravery the tale of the Sikandar Bagh might have been very different. In the meantime, those who had entered through the breach were engaged in hand to hand fighting, slowly driving the defenders before them. Burroughs was stunned by a sword cut on his head, from which he recovered later in the day, but the others joined Lumsden’s party from the main entrance. Lumsden himself fell dead as he shouted, “Come on, men! For the honour of Scotland !” And Colonel Ewart captured the colours defended by two rebel officers both of whom he killed.

Both sides fought with desperate courage. Although the rebel made a stand as they rallied round the central pavilion, the British soldiers crying, “Remember Cawnpore,” drove them to the corner building. This the rebels succeeded in holding until a gun was brought to force the heavy door and they could offer resistance no more.

The British casualties had been heavy, but the other side lost some two thousand men, all of whom lie buried in a large grave nearby, still distinguishable by the grassy mound covering it. A tablet marks the spot “where the wall of the Sikandar Bagh was breached in the assault on 16th November, 1857,” while just above it is another “erected by the officers of 2nd Battalion Princess Louise’s Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in 1869 to commemorate the part taken by the 93rd (Sutherland Highlanders) in storming this breach.” They also erected a monument a few yards from the breach in memory of the 165 members of the Regiment who were killed during the engagements.

Not far from the wall is another grave in which lies the remains of Lieutenant Francis Dobbs and five privates, all of the 1st Madras Fusiliers, who were killed in action while storming the Shah Najaf immediately after the capture of the Sikandar Bagh. There is a tablet in Christ Church erected by the brother officers of Captain John Tower Lumsden and Lieutenant John Cape, both of the 30th Regiment, Bengal Native Infantry. Captain Lumsden was born in 1823, son of an Aberdeen advocate, and was attached as an interpreter to the 93rd.

Had he lived, Colonel Ewart of the 93rd said that he would have recommended him for the V.C. According to Lord Roberts, Lumsden followed Ewart through the breach in the wall, but on that day of stress and battle who can say clearly what happened? What matters it now, except that many valiant lives were lost on both sides ?

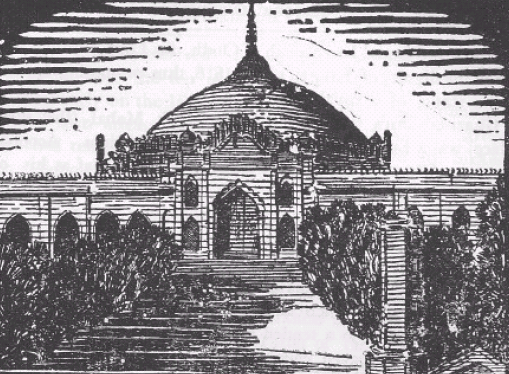

The Shah Najaf

In The Shah Najaf, Opposite the Carlton Hotel, lie the remains of King Ghazi-ud-Din and his wives. It is alternatively known by the name of Najaf Ashraf, Najaf being the name of the town in Iraq where Moslem pilgrims of the Shia sect go to visit the tomb of Ali.

Ghazi-ud-Din Haider who reigned between 1814 and 1827 was the seventh and last Nawab of Oudh, for Lord Hastings raised him to the dignity of King in about 1818, thus promoting Lucknow to the status of a royal city.

Ghazi-ud-Din’s favourite wife Mubarak Mahal (the Blessed Palace) was a European, whose real name was Miriam. According to custom Ghazi-ud-Din Haider built the Shah Najaf as his own mausoleum and his tomb of silver lies in the centre of the building, flanked by the larger and more imposing silver and gold tomb of Mubarak Mahal on one side and by a small tomb of another of his wives on the other. Still another wife is said to be buried in a corner of the main chamber.

Low white walls encircle the Shah Najaf and an imposing entrance opens on to a tended rose garden. In the centre, wide cloisters enclose a paved courtyard, and the entrance to the tomb is on the far side of the court.

At the top of a short flight of white marble steps stand finely carved sheesham wood doors from Burma. Immediately inside hang three contemporary protraits by Mrs. Jopling Rowe, of Ghazi-ud-Din and two of his successors. The walls are decorated with gilt mirrors and old pictures of Ali’s horse, Duldul, drawn in the writing of the Koran.

The King was a rich man and endowed his tomb with a crore of rupees lent in perpetuity to the British Government. Twice a year, at the Moharram festival and on the anniversary of the death of Mubarak Mahal, it is illuminated, special prayers are said and alms distributed to the poor. In 1857 the Shah Najaf was a stronghold of the mutineers and stood in the direct route of the relieving force of Sir Colin Campbell. On the evening of November 15 the look-out man on the Residency Tower received the signal “Advance tomorrow” semaphored from the top of the Martinière.

Accordingly on the 16th, Sir Colin with his force of some three thousand men advanced against about sixty thousand strongly entrenched rebels, and successfully drove them from the Sikandar Bagh. Following a brief halt they advanced on the Shah Najaf. After a three hours’ bombardment even the naval guns of the Shannon could effect no breach in the solid walls. Sir Colin called his men to the charge and the Naval Brigade, the 93rd Highlanders and a detachment of the 90th Foot commanded by Captain (afterwards Field-Marshal Lord) Wolseley, made a gallant effort to scale the walls.

Darkness was falling and success seemed impossible when Sergeant Paton of the 93rd Highlanders found an old breach. In poured the men. As they entered the mutineers bolted out of the far side. The British troops bivouacked there for the night.

Since then the ravages of war have been repaired, and no trace of the savage fighting remains. Indeed, between the mausoleum and the river Gumti lies a little building hung with curious old portraits of former kings and forgotten maulanas and wazirs, which seem to have been there since the day they were painted, so complete is the musty atmosphere of forgotten splendours of the Court of the Kings of Oudh.

Scarce-Remembered Places

Many historical places in Lucknow are too small to be recognised as “protected monuments” though they are none the less interesting for that. They are in peril of sinking into oblivion, if they have not already crumbled literally to dust.

The Wingfield Park owes its conception to Sir George Campbell, Judicial Commissioner of Oudh, who in 1860 caused some eighty acres to be converted into a park as a memorial to Sir Charles Wingfield who died during his tenure as Chief Commissioner.

Originally a walled garden occupied the site and was known as the Banarsi or Benares Bagh because of certain plants brought there from Benares. Where the marble baradari now stands, was a double-storeyed summer-house, and some of the statuary in the park once adorned the Kaiser Bagh Palaces.

Not far away on the left bank of the river stood the Chakkar Kothi or Round House, bombarded in 1858 from a battery erected on the site of the present Race Bungalow, by order of Sir James Outram. Soon after noon, on March 9, 1858, Sir Colin Campbell, who was standing on the roof of Dilkusha Palace, saw to his astonishment the regimental colour of the Bengal Fusiliers floating above the Chakkar Kothi which he believed to be in enemy occupation. It transpired that part of this regiment had taken the house after a short sharp fight.

About an hour later Lieutenant Butler, an officer of the Bengal Fusiliers, swam across the river which was there about sixty yards wide and running with a swift current. He penetrated into the canal works and found evidence of hasty desertion. He mounted the wall which stood exposed to hot fire from both sides. Eventually he attracted the attention of Sir Colin Campbell who was watching developments from the vantage point of the Martiniere and who sent a detachment of the 4th Punjabis to occupy the position. Lieutenant Butler was afterwards awarded the V.C.

The present cantonment was filled with parks and country houses belonging to the King and his courtiers. The house now used as an Officers’ Mess by a British Infantry regiment was once the country residence of the Prime Minister of Oudh. It is characterised by a fine circular domed entrance hall ornamented with stucco designs similar to the mural decorations of La Martinière College.

The Muhammad Bagh was a large walled garden extending over both polo grounds, the present club grounds, and the Presbyterian Church. It adjoined Dilkusha Park near the junction of the present Tombs and Dilkusha Roads, at which corner Sir James Outram caused a battery to be entrenched on March 8, 1858.

On the present Brigade parade ground lay the village of Ghaili where, on December 21, 1875, Outram’s spies informed him that a large force of 4,000 infantry, 400 cavalry and four guns, was drawn up with the intention of surrounding him. Accordingly, Outram divided his force which consisted of 1,200 infantry, 190 cavalry and six guns, into two. To the right lay a column under Colonel Purnell of the 90th Foot: to the left another under Colonel Guy of the 5th Fusiliers. Both advanced simultaneously to the attack, taking the enemy by surprise, routing them completely, and capturing all four guns with scarcely a casualty. The retreating force left some sixty dead on the field.

Jamaita was the name of another village situated on the Mall where the District and Brigade offices stand and extending over the site of the gymnasium. The Char Bagh garden occupied a large area now covered by railway buildings. Clustered around the Kaiser Bagh the remains of many interesting buildings still linger among those of more recent erection. There stood the Kothi Dilruba Munzil, called after Dilruba Mahal, one of Wajid Ali Shah’s wives. It belonged later to a Christian lady who died at Agra, and was occupied for many years by a Government pensioner named Piggott.

Near it the Bait-ul-Insha, or Correspondence Office, was so named by Wajid Ali Shah; but a couplet engraved over the door states that the house was built in 1240 A.H. or 1824 A.D., during the reign of Ghazi-ud-Din Haider. In the same area the Bait-ul-Iqra, or Office of Issue, was named by Wajid Ali Shah.

Within the Kaiser Bagh quadrangle stands the Qasr-ul-Buka, a striking pavilion of white marble. Built by one of the Kings of Oudh, it was originally an imambara, a place where meetings are held to mourn the deaths of Imam Hussain and his followers at Kerbala. The name Qasr-ul-Buka means “house of mourning.” The building now belongs to the British Indian Association. The hall is hung with protraits of successive presidents of the Association and is used for social functions and public meetings.

Sa’adat Ali Khan

1798—1814 . Oudh Was In A Bad Way. Money had run through Asaf-ud-Doulah’s fingers like water. After his death matters continued in the same way during the four months when Wazir Ali sat feebly upon the throne, with no thought for anything but debauchery. Then came Sa’adat Ali Khan, half-brother of Asaf-ud-Doulah.

But matters did not improve. Sa’adat Ali had possibly inherited that same strain of extravagance which had earlier been shown by his brother. Or, perhaps, sudden, access to luxury, a title, and the semblance of wealth, however unsubstantial, went to his head. At any rate, life at the court of Lucknow continued as before.

Ever more pressing and more insistent became the bills and notes of promise. So loud were the voices shouting for payment that they eventually reached the ears of the King himself. Troubles gathered thick and fast about Sa’adat Ali, until he knew not what to do. His troops were useless. There were continual and mutinous mutterings from the sepoys displeased at the abrupt departure of Wazir Ali who had included the army in his distribution of money not his to give.

Sultan Tippu of Mysore and his ally Zaman Shah were turning their thoughts and their armies towards the boundaries of Oudh. Sa’adat Ali looked in his distress to the strongest person he could think of—the Governor-General, Lord Wellesley. The latter declared that the Nawab’s army must be disbanded and replaced by the Company’s troops. The Nawab in his terror gladly agreed, but, as his fears abated, tried to back out of the agreement.

Lord Wellesley stood firm, however, and the place of the unruly rabble was filled by twelve battalions of infantry and four regiments of cavalry, costing fifty lakhs a year to maintain. This increased the annual payment due to the Company to 126 lakhs a year. The Governor- General proposed a scheme whereby the exclusive civil and military government of the state should be transferred to the Company. The Nawab flatly refused to consider this. Rather than be a figurehead, a useless puppet, he would abdicate. The alternative was to cede to the Company territory to yield a substantial part of his revenue.

Finally, in 1801, after much discussion, an agreement was reached whereby Sa’adat Ali Khan should hand to the Company certain of his lands which became known as the Ceded Provinces and which formed the beginnings of the present province of Agra. In addition, the fort of Allahabad was to be used as an arsenal by the Company’s troops.

The solemnity of the proceedings went deep into Sa’adat Ali’s heart, for he made a pilgrimage to the sacred Dargah of Hazrat Abbas in Lucknow. There he made a solemn vow before the shrine to abstain from all indulgence and debauchery of the flesh, and to give his whole attention to the right governing of his country. This vow he kept, and no sovereign of Oudh has conducted the Government with as great ability as he did for the remaining fourteen years of his life.

His portraits show him to be portly, tall and with several chins. He was clean shaven save for a small ferocious moustache. His nose was straight and aquiline and large ears protruded on either side of a wide head illuminated by suspicious-looking hazel eyes. His head-dress was formed of rolls of costly material tightly wound into a sort of hat. He wore a long brocade robe, beneath which soft and full silken trousers fell over his gold shoes with their curved points. About his waist was twisted a broad sash. He carried a long curved scimitar sheathed in purple velvet, the hilt studded with precious stones. Round his neck he wore two or three rows of enormous jewels.

Sa’adat Ali Khan had spent his youth in Calcutta surrounded by Europeans. He had assimilated many of their ideas and methods. Some say that he spoke English perfectly ; others that he could understand, read and write, but not pronounce. In any case, his devotion to, and admiration for, the Company were strong and continued throughout his life. He set about introducing reforms with a right good will. He reorganised the collection of revenue. He made large grants of land to worthy aspirants. He took pains to protect the agriculturists. In spite of his economies, he lived in a manner befitting a King. In 1805 a. lady described his usual way of living.

He kept a table which, both in appointments and in the fare provided, could vie with any belonging to men of rank in England. There were three separate dishes provided for each course. That at the upper end of the table was cooked by an English cook ; that in the centre by an Indian ; and that at the lower end was prepared by a French chef. The Nawab owned a set of Worcestershire china, complete in every detail, for dining-room, bedroom and bathroom.

He and his retainers did not gauge the function of every unit of the sets, with the result that a certain article of bedroom furniture was placed upon the dinnertable filled with milk. The Nawab, knowing that his English guests liked that beverage, could not fathom why they touched none.

Except when he gave splendid and lavish banquets, Sa’adat Ali lived sparingly. His personal habits were frugal and economical, so that he earned a somewhat unjust reputation for parsimony and miserliness. But he gained an entirely new character during the latter and greater part of his reign as being the best administrator and the most sagacious ruler that Oudh had ever seen : a character which stood out the more sharply against a background of the lavish extravagances of his brother , the former Nawab.

Gradually he developed Lucknow towards the east and although “the city of Lucknow, excepting the Nawab’s palaces, is neither so large nor so splendid as that of Benares,” it was he who built the cantonment of Mariaon across the river, his favourite shooting box of Dilkusha, the imposing structures of the Moti Mahal, the great Chaupar stables (Lawrence Terrace), and many other structures which are still preserved to-day.

He himself lived in the Farhat Bakhsh which he purchased from General Claud Martin. As early as 1801 he established a reserve treasury which grew to fourteen crores of rupees at his death.

In 1814, the last year of his reign, Lord Hastings honoured him with a visit. The royal apartments were unpretentious yet they conveyed an air of comfort. Breakfast, in those days a meal to which guests were often invited, was held in a spacious house built in the Saracenic style and protected from the fierce sun by commodious awnings. The meal consisted of tea or coffee, pilau, Indian dishes and ices.

Dancing girls entertained the guests during the meal. The King’s father had insisted that Sa’adat Ali Khan should never touch intoxicants. From the quality of the liquor kept, it seemed fairly certain that the father’s wish was respected. For all his sensible ways, the Nawab had one or two idiosyncrasies. For instance, he refused to repair the noble old stone bridge spanning the Gumti, saying that should he mend it in any way it would cause his death within the year. Similarly, in 1810 he ordered from England an iron bridge, the first of its kind to reach India, but for some reason he refused to erect it and it lay by the side of the river, still in the packing cases in which its sections had travelled from England, for nearly forty years.

Presumably Sa’dat Ali preferred to keep the reins of government within his own grasp, for his little son who had certainly not reached years of discretion was proclaimed Chief Justice. In this capacity he had to escort honoured guests to the Royal banquets. On one occasion the lady whom he came to squire kept him waiting. It was late in the evening, after a hot and tiring day, and the poor child fell asleep in the ante-room. Promptly his attendant gentleman woke him up, took him aside, and whipped him soundly for committing so gross a breach of ceremonial observance.

On July 11, 1814, Sa’adat Ali Khan died by poisoning, aged about sixty. His remains lie in the larger of the two domed mausoleums near Aminabad. Beside him, beneath the lesser edifice, lies his chief wife, Kurshaed Zadi.

Actually when he died the site where he now lies was occupied by his son’s palace, but the son, Ghazi-ud-Din Haider, who succeeded him, declared that it was only meet that, as he had taken his father’s place, his father should have his. Whereupon he pulled down his palace to build his father’s tomb upon the spot.

Sa’adat Ali left behind him nine sons. One died in the same year as his father, but an Oudh paper dated 1837 shows that at that time five of them were still alive in spite of the cruelties of their great-nephew, the notorious Nasir-ud-Din Haider, to whom nothing gave more delight than to torment the aged, the infirm, and the helpless.

Shuja-Ud-Doulah

1753-1775

Safdar Jang Was Succeeded on the throne by his son Shuja-ud-Doulah, famed far and wide for his good looks and military talents which were augmented by Herculean strength. Yet from a full length portrait, judged by modern standards, he would not be deemed an Adonis. His face was long, with fat cheeks terminating in deep lines from nostril to mouth.

A pair of moustaches, which on each side measured some four inches in length, added to his mien an air of ferocity already imparted by a pair of sharp, close-set eyes. Fashions had changed from his father’s day. Although he still wore a full skirt, it was shortened to the calf, showing a pair of top boots. The cut-away coat was trimmed with fur. He wore many fine jewels. His head-dress appears to have been made of fur, secured with a circlet of precious stones. He carried a long thin sword.

About 1760, Shuja-ud-Doulah was made Wazir of the Delhi Empire by the Emperor Shah Alam, thus carrying on the family tradition. He joined forces with the Emperor to march against the British in the name of Mir Kasim, who had been displaced from the office of Governor of Bengal. In November 1763, Mir Kasim had fled to Oudh, where Shuja-ud- Doulah accorded him a warm welcome. At the battle of Buxar on October 25, 1764, however, they were heavily defeated by the Company’s troops under the command of Major Hector Munro.

This battle finally established the supremacy of the East India Company to whom Shuja-ud-Doulah had to surrender. The Company did not then wish to extend its sphere of jurisdiction, and so in 1765 a treaty was concluded at Allahabad by which the Nawab was reinstated in his province with the exception of the districts of Allahabad and Korah. The Company declared that it would assist him with such forces as the exigencies of his affairs might require, but that should such occasion arise, all attendant expenses would be borne by the Nawab-Wazir. This treaty was the result of a personal interview between Lord Clive and Shuja-ud-Doulah. Gradually the state grew more and more dependent upon the military assistance of the East India Company.

As the French menace grew increasingly acute, Oudh clung the closer to her strong English ally; although in 1775 Warren Hastings wrote that under certain conditions nothing could prevent the Marathas laying waste the province of Oudh, in spite of attempts of the European soldiery to stop them. Opinions have been expressed that the East India Company treated Oudh badly by ignoring various treaty clauses, but the fact is that it was doing its best to combat the French, and actually it supported, Shuja-ud-Doulah loyally.

In 1768 the Nawab agreed to keep an army of a strength not exceeding 35,000 men. Five years later Mr. Nathaniel Middleton was appointed as the first British Resident in Oudh, thus virtually asserting British supremacy. At the same time a brigade, consisting of two European and six sepoy battalions and a company of Artillery, was sent to Oudh and maintained at the Nawab’s expense. The troops were stationed at Faizpur Kampu, between two and three miles from Belgram. In 1781, long after the barracks had disappeared, the names persisted in the fields, which were still called the Kamsariat (provisions), Kabarahar (cemetery) and Gendkhana (cricket ground).

Shuja-ud-Doulah lived in Fyzabad where he died in 1775 at the early age of forty-six, There he was buried beneath an imposing mausoleum. Latterly he had lived in Lucknow, as being more central, but it was left to his successors finally to transfer the capital city there from Fyzabad.

Safdar Jang

1739-1753

Famous Throughout India As Safdar Jang, the real name of the second Nawab of Oudh was Abul Mansur Khan, or Ali Mansur Khan. He was the nephew and son-in-law of Sa’adat Ali Khan, his predecessor. The name of his wife was Begum Aliya Sadru.

The Emperor of Delhi, Muhammad Shah, was engaged in a war in Sirhind against Shah Abdali when his commander, Mirza Ahmad, was joined by Safdar Jang and a number of guns; with his aid Shah Abdali was defeated three times.

On the death of the Emperor in 1749 Mirza Ahmad succeeded to the throne of Delhi, whereupon Safdar Jang, then Subadar of Oudh, followed the example of his uncle, displaying his talents at the court to such advantage that he was soon made Wazir of the Delhi Empire, an office which thenceforth became hereditary. It was usual for a Subadar to rule his ‘suba’ in the country, while his duties of Wazir were performed in Delhi by a deputy.

Safdar Jang, being of a militant disposition, warred against the Rohillas. By enlisting Maratha aid he temporarily subdued the Pathans before he took up his abode in Oudh and established his court at Fyzabad.

He continued to rent the palaces taken by his predecessor in Lucknow and finally assumed complete possession by exchanging them with a Sheikh family for seven hundred acres of land in Dugaon. He did not reside permanently in Lucknow, however, until almost towards the end of his life, but his financial ability strengthened his already influential position as ruler of Oudh. As a visible sign of his wealth and power, he built the fort of Jalalabad in the direction of Cawnpore, not far from Lucknow. This fort has lately fallen into complete ruin. It was the scene of sharp fighting in 1858, for it came into the line of defences which also included the Alam Bagh.

On January 12, 1858, the rebels planned a great attack upon General Outram’s force, and a Hindu fanatic who purported to represent Hanuman, the monkey god, led a large body of men against Jalalabad. They were repulsed and left their leader and many of their comrades dead upon the field. Another massed attack was made upon the same line of defences on February 21. This also failed. Soon Jalalabad Fort was abandoned as lacking in strategical importance, for the field of activity of the British narrowed as they succeeded in quelling disturbances. To return to the reign of Safdar Jang, his minister Newal Rai planned the great stone bridge over the Gumti at Lucknow, but died before it could be completed.

Authorities differ as to dates about this time, but it is generally accepted that Safdar Jang died of fever in 1753. His remains were taken to Delhi, where they were interred beneath the world-famous edifice known as Safdar Jang’s Tomb, to this day a place of beauty, whether sparkling in the glory of the mid-day sun, silhouetted against the soft grey half-light of evening, or silent in the mysterious radiance of the moon.

In appearance Safdar Jang was a fine-looking man. Like his uncle he wore a beard and possessed clear-cut features and an aristocratically high-bridged nose. His garments were of the finest material. Although he did not display a great number of jewels, those he wore were large and valuable. In his best-known portrait he is shown as wearing a long white robe with a swinging skirt, not unlike that of a dancing girl.

Girded at the waist was a belt which held his sword in a velvet scabbard, richly ornamented. His corsage was relieved by ropes of precious stones. Over all he wore a richly embossed coat, heavy bracelets jangling at either wrist. The pagri was loosely tied, a long aigrette fastened at the front and curled over his head. This portrait, which was executed some years after his death, contains an anachronism, for in the background is the great Chutter Munzil Palace which was not built until more than half a century later !

Sa’adat Khan

I732-I739

IN 1705 A PERSIAN LAD NAMED Muhammad Amin set forth with his father and brother from Persia to seek fame and fortune in Hindustan. A Saiyid by birth, he claimed to be a direct descendant of the Prophet himself. He came to Delhi where he attracted the notice of the Emperor of Delhi, Muhammad Shah, then much harassed by the activities of two obstreperous brothers, Abdullah and Hussein Ali Saiyids of Barhi.

Muhammad Amin, through his ability and business acumen, soon gained power and influence at the court, having been instrumental in assisting the Emperor to overcome the brothers. As a reward, he was given the rank of Burhan-ul-Mulk. In 1720 he became Governor of Agra with the title of Bahadur Jang, when he also assumed the name of Sa’adat Khan.

His executive ability and ambition made him an excellent ruler. In 1732 he was made Governor of Oudh. There he did all in his power to encourage agriculture, at the same time repressing with a stern hand those who threatened to become uncomfortably strong. A forceful and far-sighted ruler, he was also a great warrior. He slew Bhagwant Singh, the Kichi of Fatehpur, in single combat. Even when his long thick beard was white with the passing of years, in battle he was always to be seen wherever the fight was hottest, spurring his men to victory.

He spent much of his time at Delhi in close communication with the Emperor. He built himself a fort at Ajodhya, near Fyzabad, gradually encouraging the state of Oudh to become self-supporting. In time he was able to declare its independence from the Mogul Empire. Sa’adat Khan decided to visit Lucknow, then called Lakshman Kila, but he met with organised opposition from the Sheikhs, a celebrated and powerful family, several of whom had at one time or another been selected as governors and resented the advent of one with greater authoritative powers.

He therefore approached the Akbari Darwaza at the outer city wall. His entry barred, he was obliged to pitch has camp outside the town. He decided on a ruse. He invited all the Sheikhs to a great banquet and when the feasting was at its height he slipped away and entered the city, taking precautions against possible ejection. Over the main gateway the Sheikhs had hung a drawn sword, beneath which they made visitors bow in token of submission. This sword Sa’adat Khan removed. With it went the power of the Sheikhs. Inside the city were various palaces. Two of these, the Panch Mahal which was five storeys high, and the Mubarak Munzil, or ‘Beautiful House,’ Sa’adat Khan rented, although it is a moot point whether the owners ever received any payment from him.

He built several more palaces and gardens in Lakshman Kila, a name he altered to Machhi Bhawan “The Fish Fort,” to commemorate the Imperial edict which allowed him to assume the now famous fish badge. Beyond the walls of the fort he built Ismailganj, which has since been demolished. Gradually the whole became known as Lucknow, a corruption of Lakshman Kila.

The Nawab-Wazir, as Sa’adat Khan styled himself, was a noble looking man of fine physique, whose flashing eyes brooked no nonsense from his followers. His administrative skill procured him great riches with which to purchase magnificent jewels. He wore upon his head-dress an aigrette mounted upon a superb spray of diamonds. His aquiline nose smelt out any treachery which threatened him. His skin, rippling over the sturdy muscles, was fair. He had tact, ability and courage, but he was cruel and treacherous.

In 1739 he betrayed his benefactor, the Mogul Emperor, to ‘Nadir Shah, joining forces with the latter in Delhi, where he became Wazir of the Delhi Empire the same year. He did not live long to enjoy the fruits of his treachery, for he was poisoned a few months later, either by his enemies, or by his own hand in a fit of remorse. He died in Delhi, where he was buried.

His ally, Nadir Shah, bled him of many large sums of money. In spite of this Sa’adat Khan left his successor a well-filled treasury containing nearly fifteen crores of rupees.

The Residency

The Term “Residency” Now includes a large protected enclosure. Originally it applied only to the large English-looking house, colour-washed in yellow, conceived for the British Residency by Nawab Asaf-ud- Doulah in 1780 and finished by Nawab Sa’adat Ali Khan twenty years later.

The house stands upon what was then the highest point of Lucknow. It boasted three storeys. At one corner a tower projected a foot or two above the roof, bearing the flagstaff from which generations of Union Jacks have proudly waved. Wide verandahs shielded the interior from the sun. Beneath still lies a suite of tykhanas, or underground rooms, which remain dark and cool in the glare of the hottest summer day, although the narrow slits in the upper walls admit of but scant ventilation.

Until Captain John Baillie became Resident at the beginning of the nineteenth century there was no guard over the house. He, however, soon protested against this shortcoming, with the result that the Nawab built a guard house, now famous as the Baillie Gate, to be occupied by a company from Mariaon, five miles across the river.

The Marquess of Hastings records that he dined with Major Baillie at the Residency in 1814. Later the road led up the slope through some folding gates into a close, surrounded by gardens and well built houses, with barracks at the entrance. One of these houses was occupied by the Resident; another was his banqueting hall, containing apartments for his guests ; a third was unusually pleasing and assigned to guests of the King of Oudh. Stables for horses and adequate accommodation for ‘a brave retinue’ were accompanying features of this third house.

For another thirty years., until the outbreak of 1857, the community clustered about these delightful buildings on the little hill, unheeding the fate in store for them.

A brief knowledge of the events of the Mutiny is essential to appreciate the ruins of the historic enclosure. Things began to move imperceptibly many months before the actual outbreak. The first tangible evidence of the Mutiny in Lucknow was on May 2, when the 7th Oudh Irregulars at the Moosa Bagh refused to bite the new cartridge. After that incident the rebels became ever braver until their sense of superiority was complete.

The events of the siege proper could not be better summed up than in the words set upon a tablet on the wall of the women’s quarters, above the tykhanas of the Residency. “On 30th June, 1857 A.D., the day after the battle of Chinhut, the siege began. On the 2nd July, Sir Henry Lawrence was mortally wounded by a shell which burst within the Residency building. The command then devolved on Brigadier J. E. W. Inglis of Her Majesty’s 32nd Regiment. The force within the defence then consisted of 130 officers, British and native, 74 British and 700 native troops and 150 civilian volunteers.

There were 237 women, 260 children, 50 boys of La Martinière College, 27 non-combatant Europeans and 700 noncombatant natives, being a total of 2,994 souls. From the 30th June to the 25th September, for eighty-seven days, they were closely invested, subjected to a heavy artillery fire, day and night, on all sides, and had to sustain several general attacks on the position. On the 25th September, 1857 A.D., Generals Outram and Havelock, with a large force, endeavoured to release the garrison, after having, with great loss, effected a juncture with them.

They were, however, unable to withdraw, and the whole combined force was besieged for a period of fifty-three days, until finally relieved by Sir Colin Campbell on the 17th November, 1857 A.D. There remained of the original garrison, when relieved on the 25th September, a total of 979 souls, including sick and wounded, of whom 577 were European and 402 natives.” So emaciated and weakened was every living thing within the Residency that those camels and horses which had survived when the time came for the final exodus found it scarcely possible to drag one limb after the other.

The first night of freedom was spent at the Secunder Bagh, the weak refugees starting fearfully at every untoward sound. The following day, on crept the pitiful train to Dilkusha, ‘Heart’s Delight’. For these hearts which had suffered so much in those few short months, there can have been little delight.

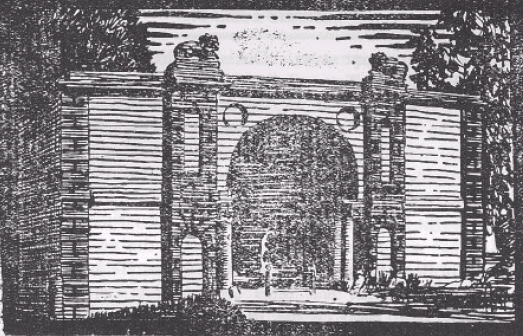

The Baillie Guard Gateway

The Baillie Guard Gateway from which the gate has long since disappeared was, during the siege, effectively banked with earth and sandbags from the inside. To the right a battery of two nine-pounders and an eight-inch howitzer defended the entrance. On September 25, Havelock at the head of his relieving force reached the famous gateway as darkness fell to find the barricade impassable owing to its fortifications.

A gun thrust through a breach was hastily withdrawn, and the troops marched in, Havelock and Outram riding at their head, to receive a welcome that only those who were present could ever fully appreciate. An hour or two later despair fell deeper by sharp contrast, when the beleaguered garrison realised that the force was no relief at all but an added burden, requiring food, accommodation and ammunition, all of which were already at a premium.

As Havelock’s force streamed through the breach, men of his troops, their blood heated to fever point from fighting every inch of their way through the streets of Lucknow, bayoneted by mistake three of the sepoys belonging to the 13th Native Infantry. “Kuch parwa nahin, Kismet hai …Baillie Guard ki jai,” they said. “Never mind. It was fate. Victory to the Baillie Guard.” Although these men had been within speaking distance of the enemy throughout the siege, no threats or cajoloments could persuade them to desert. Lord Canning wrote: “Their courageous constancy under the severest trials is worthy of all honour.” After the Mutiny the three faithful regiments, the 13th, 48th and 71st Native Infantry Regiments were formed into the 16th (Lucknow) Rajput Regiment.

The Treasury

The Treasury stands immediately on the right of the Baillie Guard entrance, the long centre room being commandeered during the siege for the manufacture of Enfield cartridges. Lieut. Aitken commanded the garrison composed of detachments from the 13th and 48th Native Infantry Regiments, to the former of which he belonged. He was assisted by Loughman with whose help they constructed and manned an eighteen-pounder gun. It is recorded that he commanded the sepoys “with signal courage and success”. They had also to garrison the Baillle Gate, holding it against great odds in the assault on July 20. Lieut. Aitken gained the V.C. for various acts of gallantry at Lucknow. Some years later he became Inspector-General of Police in Oudh.

Just above the Treasury is the BANQUETING HALL, also under the command of Lieut. Aitken during the siege. Originally it served the double purpose of Banqueting Hall and Council Chamber. Above the Resident’s offices on the ground floor were luxuriously furnished apartments reserved as guest rooms.

The building made an admirable hospital. One room, on the north side, was set apart for state prisoners, including Mustafa Ali Khan, a brother of the ex-King of Oudh, the Rajah of Tulsipore and two princes related to the Emperor of Delhi. One of the latter, Nawab Nakun-un-Doulah, died during the siege. He was buried at the gate of Ommaney’s post opposite the front entrance to the Residency proper. The enemy knew, through spies, that prisoners were kept in this building and forbore to fire heavily upon it.

Here the Reverend Henry Polehampton, during his ceaseless tending of the sick, was severely wounded on July 8. His devotion was such that “he never swerved from this self- imposed duty and only left the hospital to go to his meals.” He was well on the road to recovery after his wound when he contracted cholera. He died less than a fortnight later. Towards the end of June, he and his wife had moved into a small room in the hospital building where Mrs. Polehampton busied herself with the sick.

DR. FAYRER’S HOUSE stands across the road opposite to the Banqueting Hall. Dr. Fayrer was the Residency surgeon at the time of the Mutiny and showed all the kindness in his power to the poor refugees who crowded into the Residency at the order of Sir Henry Lawrence. Dr. and Mrs. Fayrer were a young couple who had a beautiful baby boy. At the beginning of the siege he was eleven months’ old, and the plaything of all the inmates of the house. By the beginning of August, through lack of good nourishment, poor little Bobby Fayrer was very ill. Never had there been such a sad change in any baby. From being a “lovely cherub of a child” he had shrunk to mere skin and bones and looked like a little wizened old man.

For the women, cooped up in the house, life was extremely monotonous. Each day they rose at four o’clock and sat in front of the house, where they drank a little tea and ate biscuits while such delicacies lasted. At eight o’clock they went indoors and busied themselves with setting their rooms in order. They would then put the finishing touches to their toilet before reading the Psalms and Lessons of the day, and praying.

Breakfast was at ten The rest of the morning they would sit together in the drawing-room, where the temperature was about ninety-three, sewing or playing with the children. They dined at four. When the sun set they emerged from the sheltering stone walls to have tea and ices. Prayers were again said at ninethirty. After that they went to bed in stuffy little rooms even hotter than the drawing-room. The only change or excitement was in the shape of bad news or horrible alarms.

Many of them slept together in the tykhana where they spread mattresses on the floor, lying cheek by jowl so as to reap the maximum benefit from the punkah. The room had nothing but skylights, so they ate their meals by the fitful light of a candle. The normal fare was stew “as being easiest to cook ; It is brought up in a large deckgee so as not to dirty a dish, and a portion ladled out to each person. Of course, we can get no bread or butter, so chupattis are the disagreeable substitute.

Two eighteen-pounders came through the room Emmie and I used to sleep in, and where we have since always gone to perform an alarmed and hurried toilet. We dress now in a tiny barricaded closet out of the dining-room where no balls have come yet. We are all going to sleep in the dining-room to-night. The tykhana is too damp, everyone is ill and the dining-room is tolerably safe.” Mercifully, the summer of 1857 proved a remarkably mild one. Instead of the relentless succession of days of burning sun, sullen clouds shielded the earth from unbearable heat.

When Sir Henry Lawrence was wounded he was removed to Dr. Fayrer’s house where Mrs. Harris, wife of one of the clergymen., stayed upstairs all day to nurse him. He lingered for a day or two in extreme suffering, for “his screams are so terrible I think the sound will never leave my ears.” He died at a quarter past eight on the morning of July 4.

The Fayrers’ house was built on sloping ground so that on the Residency side it had but one storey and on the city side two. Captain Weston of the Oudh Police defended it with sepoy pensioners, for its flat roof encircled by sandbags afforded a point of vantage for sharpshooters. Below was a battery of brass nine-pounder howitzers and an eighteen-pounder gun. SANDERS’ POST was originally the Financial Commissioner’s office, and was a big double-storeyed house manned by men of the 32nd under Captain Sanders of the 13th Native Infantry.

Sago’s House

Sago’s House was another of the front line defence posts which, owing to its salient portion, was particularly vulnerable. It was a small one-storeyed building exposed on three sides to tbe enemy, and formerly belonged to a school mistress, Mrs. Sago. During the siege this house was garrisoned by a party of the 32nd under Lieut. Clery.

Germon’s Post

Germon’s Post was within a stone’s throw of Sago’s House. Transit from one to the other was down a narrow passage and was fraught with much danger. Formerly the Judicial Commissioner’s office, it was commanded by Captain Germon of the 13th Native Infantry and garrisoned by some of his own Sikhs and by uncovenanted civilians. It was a big twostoreyed house which sheltered the families of the uncovenanted civilians. So near were besieged and besiegers that instead of bullets rounds of abuse were often exchanged which may account for the fact that several feet of the walls are still standing.

The Post Office

The Post Office lay behind and to one side of Germon’s Post, and on slightly higher ground. In front of it were placed a couple of mortars and four guns. Now only a pillar remains to mark the position of what was then a building housing a large number of European soldiers and several families. It was an important defence post, an officer constantly remaining on watch upon the roof. The gallant Captain Barnard McCabe of His Majesty’s 32nd Regiment was in command, although the position was the headquarters of both the Royal Engineers and the Artillery. Captain McCabe was mortally wounded when leading his fourth sortie. He died on October 4.

The Thug Gaol

The Thug Gaol was a long narrow building in the second line of defence, in the cells of which many women and children were housed. Some thirty years before the Mutiny, the Hon. Emily Eden noted in her diary that on her flying visit to Lucknow she was taken for a hurried look at the Thug Gaol.

Anderson’s Post

Anderson’s Post was a small double-storeyed house lying upon a slope in what was one of the most exposed positions of the entrenchment. By the middle of July the brick-work had been entirely shot away. Throughout the siege the enemy was never more than forty yards away, keeping up an incessant fusillade. Captain Anderson of the 25th Native Infantry commanded it with a small garrison of nine privates and a sergeant of the 32nd, a subaltern, and eight volunteers, amongst whom was an Italian Signor Barsetelli whose unending sense of humour played no small part in keeping up the courage of his fellows.

The Cawnpore Battery

The Cawnpore Battery, hard by Anderson’s Post, consisted of three field guns, but it was such a dangerous position that the garrison was relieved every day by a Captain and detachment of the 32nd. It commanded a wide area of hostile ground, including two main roads of strategic importance.

Duprat’s House

Duprat’s House was in an open position next to the Cawnpore Battery. Its owner, M. Duprat, was a Frenchman who had come from Calcutta to set up as a merchant, and who became known as a gallant soldier, as well as a popular member of the garrison. He succumbed to a wound in the face during August.

The Martiniere Post

The Martiniere Post was a strongly built house. Underneath it were tykhanas and adjoining it outhouses, the property of an Indian banker named Shah Bihari Lall. It was only thirty feet distant from Johannes House, a point in possession of the enemy. The Martinière Post was garrisoned by a detachment of the 32nd Regiment, the masters, and about fifty of the bigger boys of the Martinière College, under the command of Mr. George Schilling, Principal of the College. The smaller boys, of whom there were about fifteen, were told off to run messages to the hospital, etc., during hostilities. They proved willing little helpers.

Surprisingly, only three boys were wounded during the entire siege, and two died of disease. THE NATIVE HOSPITAL lay behind the Martinière Post which protected it from the enemy’s fire. A mortar was near by.

The King’s Hospital

The King’s Hospital, a little further on, was in the front line of defence. Later, during hostilities, it was known as the Brigade Mess.

Here were quartered the officers of regiments which had mutinied. Here also lived Mrs. (afterwards Lady) Couper, wife of Sir Henry Lawrence’s secretary, in a room some ten feet square, with many other women and children. The building, solid and spacious, gave a good view of the city from the roof. Colonel Master of the 7th Light Cavalry got his nickname of “The Admiral” owing to his habit of hailing from the roof top. The officers found this roof a good vantage point for sniping.

It was largely owing to their good marksmanship that the enemy attacks on August 11 and 18 failed. Known to be a dangerous post, the enemy rained bullets into it on every occasion until, by the end of August, the upper part had become a mere ruin. On September 7 two hundred and eighty round shots were collected from it, varying in size from a twenty-four pounder to a threepounder. At the back were the Brigadier’s quarters and those of Lady Inglis and her children.

Johannes House

Johannes House stood exactly opposite to the Brigade Mess, but outside the line of defences. Previous to the outbreak of hostilities Johannes, an Armenian, was the richest merchant in Lucknow. It had been intended to include his house within the Residency area, but so swift was the debacle after the battle of Chinhut that the enemy occupied it before the British could do so.

The Armenian’s house remained a constant source of trouble until August 12 when a cunningly placed mine exploded and the whole building tumbled to ruins, dragging with it a number of mutineers. Chief amongst its garrison was an African, formerly in the army of the King of Oudh, whom the defenders nicknamed “Bob the Nailer”, for his aim was so accurate that every shot he fired literally “nailed” his man.

The Sikh Square

The Sikh Square consisted of two quadrangular courtyards surrounded by low flatroofed buildings and a horse picket yard for fifty cavalry and artillery horses. It adjoined the Brigade Mess and was garrisoned by the Sikh Cavalry and some Christian drummers under the command of Captain Hardinge of the Oudh Irregular Cavalry and other officers who were relieved in weekly rotation. The loyalty of the Sikhs was a much debated question, but the majority of them remained staunch and proved invaluable as miners. For this hazardous work each man was paid at the rate of two rupees a day.

The Begum’s House

The Begum’s House behind the horse-lines of Sikh Square was a large building on the roof of which the two minarets and three domes of a small mosque still stand. The house was the dwelling of a Mrs. Walters and her elder daughter who was known as Begum Ashraf-ul- Nisa. The younger daughter, under the title of Mukhaddar-i-Ulaya, had married King Nasirud- Din Haider, who reigned from 1827 to 1837.

Ommanney’s House

Ommanney’s House stood close to the Begum’s House some way back from the front line fortified in case the troops should have occasion to fall back upon it. GRANT’S BASTION occupied a prominent position, separated from Sikh Square by a long narrow passage in possession of the enemy, at the blind end of which stood a British mortar.

Gubbins’ Battery

Gubbins’ Battery was an outwork which protected the south-west corner of the position, and was garrisoned by covenanted civilians. Many of their names have since become famous, such as Ommanney, Couper, Martin, Capper Thornhill and Lawrence. GUBBINS’ HOUSE stood not far from Gubbins’ Battery, but scarcely anything except the swimming bath remains of what was once a large house with an imposing front portico. Water was plentiful throughout the siege, and this swimming bath was a great boon.

At first the house was filled to overflowing with ladies and children occupying the upper storey, but towards the end of August it became unsafe from the number of round shot poured into it by the enemy, so all but the garrison vacated it. Details of the 32nd, the 48th Native Infantry, Pensioners and Gubbins’ Levies comprised the garrison under Major Banks, Captain Forbes, 1st Light Infantry, Captain Hawes, 5th Oudh Irregular Infantry, and finally under Major Apthorpe, 41st Native Infantry.

Major Banks was mortally wounded at this post, also Captain Fulton of the Engineers, who by general consent was accorded the palm of merit for his conduct during the defence. Mr. Gubbins was financial secretary of Oudh and he afterwards wrote an illuminating book about the siege.

The Slaughter-House

The Slaughter-House POST lay along part of the west wall of the defences. It is now only marked by pillars, but originally consisted of outhouses belonging to the Residency, including a sheep pen and a slaughter-house. They were held by uncovenanted civilians under Captain Boileau of the 7th Light Cavalry. Nearly every officer who slept there contracted fever owing to the unwholesome and overpowering stench which arose from the decaying entrails of the butcher’s dally victims. These were simply thrown over the parapet as the only means of disposing of them.

St. Mary’s Church

St. Mary’s Church, a handsome Gothic building, had been erected in 1810. Well shaded by trees and surrounded by a wall, it had no churchyard for the good reason that India did not bury her dead near churches in those days. The east window was an imitation, likewise the side aisles which were verandahs where slood the punkah coolies. The church held a hundred and thirty people.

The first to be buried in the church garden were the victims of the surprise attack upon Mariaon. During the siege, the church, standing on a slope, was very exposed. In spite of this, services were regularly held. Artillery horses were picketed in the garden, and stores stowed away in part of the building itself. The vestry and other shelters housed refugees, giving the church a most warlike appearance. At one time the authorities seriously considered blowing it up. The idea, however, was abandoned because it involved the useless expenditure of gunpowder.

Burials were conducted under cover of darkness by two gallant padres, Harris and Polehampton. It was impossible to dig very deep, partly owing to the time factor, and the bodies were merely wrapped in sheets and laid in the ground, with the result that the churchyard developed a most offensive smell, making the wretched clergymen ill. Polehampton died from cholera contracted while convalescing from the effects of a severe wound. His young wife, who had but lately lost her only child, was anxious that her husband should have a coffin, a simple wish that seemed impossible to gratify, for wood was at a premium.

A search was made, however, and an old coffin found, stowed away with some boxes under a staircase at the hospital. He was duly buried in a separate grave. During the siege those who died were normally sewn up in their bedding and buried in one grave. The death of the brave clergyman was a serious loss, for he had been unremitting in his kindness to the sick and wounded in the hospital. He never swerved from a self-imposed duty, and only left the hospital to go to his meals.

Innes House

Innes House stood on an exposed peninsula of ground below the church, and separated from it by a low mud-wall. It was originally occupied by Lieut. James McLeod Innes of the Bengal Engineers. During the Mutiny a party of the 32nd Regiment defended it, augmented by a handful of sepoys of the 13th Native Infantry, and by some uncovenanted civilians, all under the command of Lieut. Longman of the 13th Native Infantry and later of Captain Craydon of the 44th Native Infantry.

The house itself was large and well-built, with a sloping roof and verandahs on two sides. An inside staircase led to the roof. In one corner of the compound stood a small double-storeyed shed, the upper floor being known during the siege as the cockloft, commanding a view of the Iron Bridge spanning the Gumti.

On July 20, a massed attack was launched against the Residency with Innes House as its primary objective. The enemy came within ten yards of the stockade carrying scaling ladders, but met with such a hot reception that they were forced to retire as attack after attack repeatedly failed.

They nearly succeeded, however, in occupying the cockloft. Mr. Ereth, a corporal in the Volunteers, rushed forward through a hail of bullets only to fall mortally wounded in the neck. He was a railway contractor who had been married a bare three months. Such was his self-effacement and keenness that when he lay dying in hospital, he asked whether all was going well at Innes Post. No sooner had he fallen than Mr. George Bailey, another volunteer, doubled up with a few sepoys who succeeded in holding their own in spite of being badly wounded.

The insurgents continued to make isolated attacks on the various outposts during the whole morning, but contented themselves in the latter part of the day with heavy musketry and gun fire. At the diagonally opposite corner of Innes’ enclosure a rebel standard-bearer was actually shot in the ditch of the Cawnpore Battery,, so close had he advanced. In spite of fierce fighting the British losses were only four killed and twelve wounded. Lady Inglis records that “this attack and its complete repulse raised all our spirits and gave us confidence that with God’s help we should be able to hold out till succour arrived. It was the severest assault that the enemy had yet made, and John said the bullets fell like hail.”

The Redan Battery

The Redan Battery stood not far from the Water Gate. It was built during June by Captain Fulton, a Sapper, and a very gallant man. He discovered some Cornish miners in the ranks of the 32nd, and with them conducted all the mining of the siege. There is in Lucknow a picture of him crouched in a mine, revolver in hand, like a terrier at a rat-hole. He was wonderfully brave, and took great risks with supreme modesty.

He was killed on September 14 by a round shot, having won from his comrades the title of “The Defender of Lucknow.” The Redan Battery was the strongest within the defences, having two eighteen-pounders and one nine-pounder with which to rake the riverside. It was manned by men of the 32nd Regiment under one of their own officers, Lieut. Sam Lawrence. Here it was that Mr. Ommanney, the Judicial Commissioner, was fatally wounded by a cannon ball which struck his head. Two enemy attempts were made to blow up the battery, but in vain.

The Taluqdars’ Hall, Clock

Tower And Daulat Khana

Past The Great Imambara, through the Rumi Darwaza, on the right hand side of the road, lies the Husainabad Park wherein are several buildings of interest. The Taluqdars’ Hall, a rectangular red brick building, characterised by ornamental terra cotta-coloured iron pillars, was built by King Muhammad Ali Shah, who reigned from 1837 to 1842.

He it was who slept peacefully in a small room in the Chutter Munzil Palace, while the Begum was trying to install her adopted grandson Moona Jan on the throne, following the poisoning of Nasir-ud-Din Haider that same evening. The building is alternatively known as the Baradari, which means “room with twelve doors”, i. e., a reception room. Interesting are the three high flood marks on the outer wall of the porch, the highest being that of 1923. From the porch a wide flight of steps leads to the interior of the building, where several rooms are now used as offices and record rooms—the largest as an assembly room for the Taluqdars of Oudh.

Round this room hang ten portraits, the work of two artists, depicting the rulers of Oudh, beginning with Nawab Sa’adat Khan and ending with King Wajid Ali Shah, who was deposed and sent to Calcutta where he died in 1887 at the age of sixty-seven. It is interesting to note the changes apparent from generation to generation. Sa’adat Khan was a strong purposeful man with a long cruel nose. Gradually the stature of the rulers dwindled, their countenances became less those of men of character and more of men who led dissolute lives. Each one is loaded with magnificent ropes of pearls and other priceless jewels.

The banqueting hall gives on to a spacious verandah looking out on the Husainabad Tank, a prosaic enough name for the lovely sheet of water. It too was built by Muhammad Ali Shah. It is well stocked with fish. Tradition has it that it was originally connected with the river. Now only occasional pairs of geese or jumping fish disturb its placid green depths.

Reflected on its surface is the Husainabad Clock Tower, an ugly structure built in 1881 at a cost of nearly Rs. 20,000 donated by the Trustees of the Husainabad Endowment from the income on a legacy of thirty-six lakhs of rupees bequeathed by Muhammad Ali Shah for the upkeep of the lesser Imambara. A chime of five bells announces the hour quarters shown by the clock which is said to be the largest in India, and which has an ingenious lighting system.

On the opposite side of the lake, behind a belt of trees, stands an unfinished structure known as the Sat Khanda, or Seven-Storeyed Tower. This also was built by Muhammad Ali Shah, but he died when only four storeys had been completed, so the work on it was abandoned, and it stands to this day an unfinished memorial to this eighth ruler of Oudh, who spent large sums in making the Husainabad a broad and handsome street. Towards the end of his reign he was almost completely bed-ridden. It was his intention to be carried up the circular staircase of the Sat Khanda, now crumbling to dust, and there to lie upon the roof. There he could watch his plans for the beautifying of Husainabad mature.

Within the same little park stands a gateway leading to the Daulat Khana—a name embracing a collection of buildings—which means “Nobleman’s Mansion.” Several of these houses are of handsome aspect and are in good repair, although now surrounded by bazaar hovels. They were the original dwellings of Asaf-ud-Doulah and his court who took up their abode there when they transferred themselves and their capital from Fyzabad to Lucknow in 1775.

This group of buildings escaped the rough passage of the Mutiny, except for the Daulat Khana, which was occupied without resistance on March 17, 1858, by Sir James Outram’s advancing force.

The Tara Wala Kothi

The Tara Wala Kothi, now the Imperial Bank building, was built by direction of Nasir-ud-Din Haider, King of Oudh, who reigned between 1827 and 1837, and under the supervision of Colonel Wilcox, his Astronomer Royal.

It was fitted with astronomical instruments. Colonel Wilcox fulfilled his duties until his death in 1847, when King Muhammad Ali Shah who had succeeded his nephew allowed the post to fall into abeyance. Who Colonel Wilcox was is not known, save that he was a pensioner in Oudh. He was the last person known to have been buried in the old graveyard near Aminabad.

Nasir-ud-Din Haider did not lead a particularly exemplary life. His reign was marked by increasing signs of degeneracy. Several Europeans were in his employ, perhaps the most notorious being the famous barber, de Roussett, who exercised the most pernicious influence over the King. The King made not a murmur even when the barber’s monthly bill measured four and a half yards in length and amounted to more than ninety thousand rupees, then the equivalent of nine thousand pounds.

It may well be imagined that but few records remain of the more sober activities of his time. Some years later the Tara Wala Kothi was used for the local courts of civil justice. Gubbins, who describes it as a handsome and classically designed building, says that it was protected by a regular guard of Native Infantry while several European officials occupied detached residences nearby.

In the insurrection of 1857 one Chimad Ullah Shah, an influential Moulvi of Fyzabad, adopted the Tara Wala Kothi as a meeting place for the rebel parliament. This Moulvi was usually known as Dunka (Drumbeat) Shah, for he employed a man to walk in front of him beating a drum wherever he went.

During the second relief of Lucknow, the Tara Wala Kothi was in the direct line of advance. From the sand-bagged roof the relieving force knew that the enemy were resolved to defend it. The guns of the Shannon forced a passage hard by the 32nd Mess House but the sailor gunners were obliged to retire, owing to heavy musketry fire from the roof of the Tara Wala Kothi. On November 17, however, Sir Colin Campbell’s relieving force made heroic onslaughts upon the 32nd Mess House.

At three o’clock it was captured, as was the Tara Wala Kothi, and volumes of smoke issued from its lofty windows. With the capture of these two buildings the third line, of the enemy’s defence was broken and their courage shaken. About six thousand of them saw that their line of retreat was in danger of being cut off, so they fled towards the Cheenee Bazar and the Kaiser Bagh.

During the Mutiny the astronomical instruments all disappeared. Only hearsay tells that once a brass pillar stood in the central chamber and reared its head through the roof. To this day a pillar stands close to the house, sole survivor of the appliances in use when the building fulfilled its original purpose.

Although the Fyzabad Moulvi does not appear by name in the records of the hand to hand fighting round the Tara Wala Kothi, he is again heard of on February 15, 1858, when he led a strong body of horse and foot against the British forces. Major Olpherts galloped up with two guns and a troop of the military train and repulsed the attack, in which the Moulvi was severely wounded. Soon afterwards he returned undaunted to Lucknow with a large force and two guns, and occupied a strongly fortified position in the city. On March 21, a force consisting of parties of the 93rd Highlanders and the 4th Punjab Rifles was sent against him, and after a hundred and fifty of his men had been killed in a short but exceedingly sharp encounter, he and his remaining men fled. Although they were pursued for about six miles, the Moulvi himself escaped and disappeared into oblivion.

Years later the building, which consists of very few, very large and very lofty rooms, was restored and the existing bank premises were added. Early in October 1923, there were serious floods, and Mr. Davis, the occupant of the house, woke up one night to find that the water had risen half way up the entrance door. Immediately, with the help of two others, he constructed a raft of boxes, in case the water should rise higher before morning. For about a fortnight the building was isolated: staff and clients having to be ferried to and from the Mall by boat.

Wide lawns and shady trees now set off the stately and spacious building, characteristic of the years when the Kingdom of Oudh was of some account in the oriental world, and before the degeneration of luxury signed the death warrant upon the fortunes of the dissolute kings.