The Tibeto-Burman Sub-Family of Indian Languages

This article has been extracted from |

NOTE: While reading please keep in mind that all articles in this series have been scanned from a book. Invariably, some words get garbled during Optical Recognition. Besides, paragraphs get rearranged or omitted and/ or footnotes get inserted into the main text of the article, interrupting the flow. As an unfunded, volunteer effort we cannot do better than this.

Readers who spot errors in this article and want to aid our efforts might like to copy the somewhat garbled text of this series of articles on an MS Word (or other word processing) file, correct the mistakes and send the corrected file to our Facebook page [Indpaedia.com] Complete volumes of the LSI are available on at least 3 websites (Joao, Archive, UChicago), against which errors can be checked and corrected.

Secondly, kindly ignore all references to page numbers, because they refer to the physical, printed book.

The Tibeto-Burman people

We have seen that the Tibeto-Burman people first of all split into two branches

Branches of the Tibeto- // Burman Sub-Family.

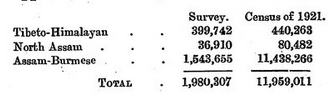

mutual relationship of the three branches one going north and west along the valley of the Sanpo into Tibet, and the other remaining on the south side of the Himalaya to populate Assam and Burma. So early an ethnical division naturally leads us to expect a corresponding division of languages, and such indeed is the case. Philologists have hitherto divided the Tibeto-Burman sub-family into two main branches, the Tibeto-Himalayan, and the Assam-Burmese or Lohitic. To these we must add a third, miscellaneous group, which, for the sake of convenience, we may call the North Assam Branch.So far as up to the present has been ascertained, this last occupies an intermediate position between the two others, and is spoken by tribes whose ancestors appear to have migrated thither independently, and at different times, from the original.

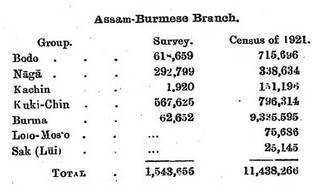

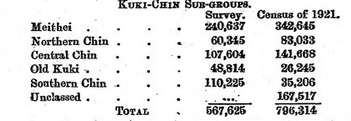

Nidus of the Tibeto-Burman race .On the margin I give the number of speakers recordedfor each branch in the linguistic survey and in the Census of 1921. For the Assam-Burmese are much less than those of t he Census,s.S the former did not cover auything like the whole Assam.-Bu~mese a~. Accessions of territory, or a widening sphere of political interest, accounts for ,the large number of speakers of the North Assam branch recorded in the Census

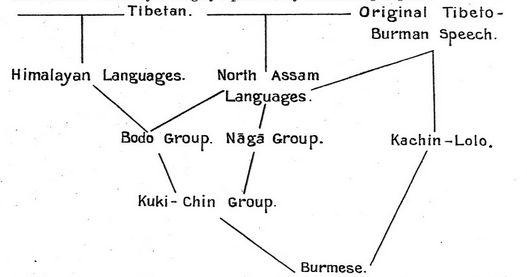

This division of the Tibeto-Burman languages is not, however, so simple as it Mutual relationahip of the seems. The question is oonsidered in detail on pp. lOff. of Volume III, Part i, of this Survey, and here it must suffice to give the broad results so far as we have been able to ascertain them. The most northern representative of the Tibeto-Himalayan Branch is Tibetan. and the most southern representative of the Assam-Burmese Branch is Burmese. Between them lie all the other Tibeto-Burman languages. The two extremes are connected along two distinct linguistic chains. The eastern chain consists of the Kachin and Lolo forms of speech, which connect Tibetan. directly with Burmese. The western chain is at first a pair of chams each beginning in a difterent locality. but joining together lower down, like t he letter Y.

The joint chain then goes on and ends a.gain in. Burmese. The eastern limb of this Y begins .with the miscellaneous forms of speech which m.a.ke up the North. Assam Branch and Continues through dialects of the Naga Hilla into those of the Bodo and Kuki-Chin groups. where it meets the other, western. limb. The latter begins with those dialects •of Tibetan. which have crossed the Himalayan watershed from the North and have occupied the southern face of that range. These also lead us into Bodo and Knki-Chin. The joined .eastern and western limbs then lead us, like Kachin and Lolo, into Burmese. This may be roughly represented by the following diagram :-

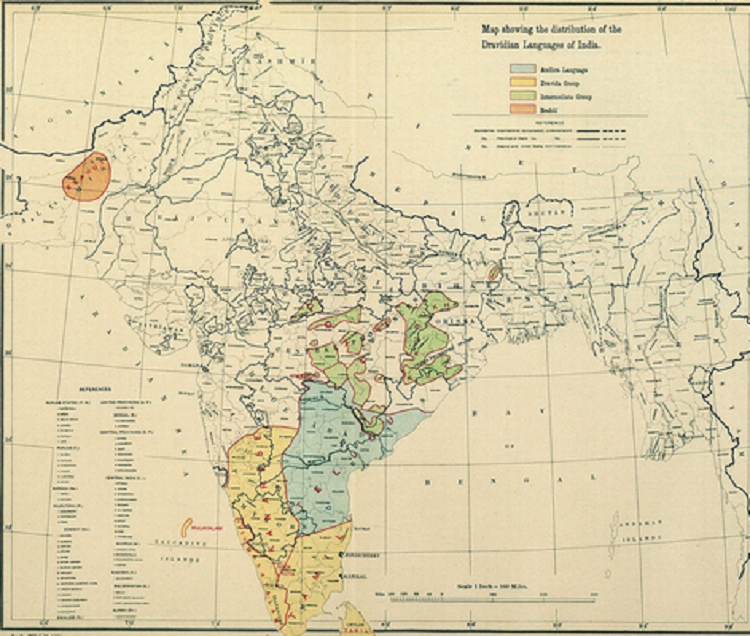

The localities in which these groups are severally spoken are shown in the map facing the preceding page

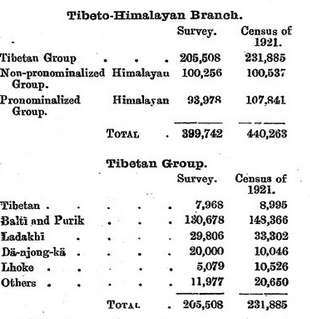

Tibeto-Himalayan Branch.

The Tibeto-Himalayan Branch falls more easily into three well defined groups. The first, or Tibetan, Group consists of those forms of speech which we may call by their general Indianname of ` Bhotia, ' and of which the most prominent representative is Tibetan, or the Bhotia of Tibet.

This last named language hardly concerns us, as the Survey does not extend to Tibet proper, but other forms of Bhotia, which from another point of view may be looked upon as dialects of Tibetan, are found in Baltistan and Ladakh, and have crossed the Himalaya into the northern parts of lahoul, Spiti, Kunawar, the State of Garhwal, Kumaun, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. Tibetan proper Possesses tones, due to the loss of old prefixes, but as we go west wards into Ladakh and "Baltistan we find many prefixes still in vigorous existence. and, as a consequence, no tones in use. Standard Tibetan has a great literature, but the others are mostly corrupt dialects with no written recordes.

'I'he presence of -the few speakers of standard Tibetan in British India is accidental, and need not detain us long. Nevertheless,from the point of view of philology and on acount of its literature,the Ianguage is of great importance, and, though there are so few speaker in India, its connexion with India is intimate. It was from India that Tibet received the Buddhist religion and the scriptures that expIained it.

Tibet's very alphabet is of Indian origin, and its earliest literature, dating from the 7th century A..D., consists mainly of translation of Indian books, many of which are now lost in their ori• ginaLform. It was these translations that changed the rude speech of the Tibetans into a copious litemry Ianguage capable of reproducing the infinite wealth of Sanskrit in a manners at onces litral and faitful to the sprit of the orginal.

The standard form of Tibetan is that spoken in Central Tibet, in the provinces of U and Tsang, and several dialects spoken in other parts of that country have been catalogued in Volume III, Pt. i of this Survey. So far as India is concerned, it will be sufficient to consider two groups of dialects, -- an Eastern and a Western. The Eastern includes Lhoke, the language of Bhutan; Da-njong-ka, the form of Tibetan spoken in Sikkim; Sharpa and Kagate of Nepal, and minor dialects found in Kumaun and the State of Garhwal. In Ladakh and Baltistan we find the Western Group. Ladakhi has been sufficiently studied to have a dictionary, and several texts in the dialect have been published by Mr. Francke and other missionaries stationed at Leh.

Balti, with a peculiar character of its own, now obsolete, owns some hiatorical books, but cannot now be called. a .language with literature.

At the present day, the population being ,Musalman, the Persian character is used for writing it. and in this medium we have translations of the Gospels and & few Christian tracts published in the modern language. Immediately to the East of Balti, between it and Ladakhi, lies the closely allied. Purik, and, for statistical purpose, the two dialects have been treated as one with a joint total for the number of their Speakers. As already stated, Balti and Ladakhi to have large extent retain the ancient prelixes lost by standard Tibetan, and consequently they have not developed tones.

The above Tibeto-Burman languages are all forms of speech which can at once be

Recognized as dialects of the bhotia of Tibet (that is Tibet).several of them have cross the Himalayan water shed and are now spoken of the south side of the great range. Their arrival there must have been at a comparatively .late period, for their speakers still acknowledge the relationship with

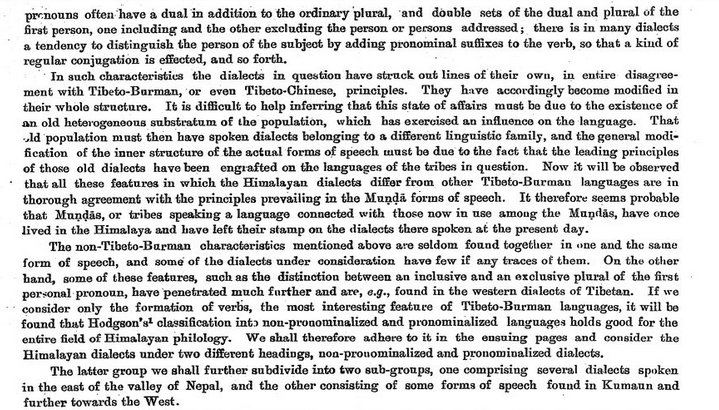

the parent language. But there is an older set of languages of the same sub--family, which must have crossed. the Himalaya from the North before the language of 'tibet had established itself in its present form, and which have, in the sites where we now find them, had their own history and, independenly of Tibetan, their own development, although their more distant relationship with that language cannot be denied.. These are called the" Himalayan" Tibeto -Burman languages, and. their general characteristic are thus described by Professor Konow.-2

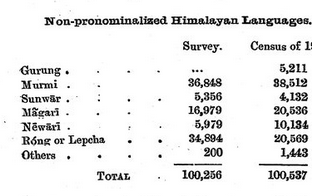

The Non-pronominalized dialects are spoken in Central and Eastern Nepal, and further to the East, in Sikkim and Bhutan.

As most of them are spoken in Nepal, the statistics given on the margin are necessarily' incomplete, for the numbers given represent only those speakers, (mostly soldiers in our Gorkha regiments or immigrants to Darjiling)who were found in india proper .The bulk of the speaker who reside in Nepal,is altogether omitted from considerntion. On the other hand, thanks to the kindness of the Nepal Government, the Survey has been supplied with very complete specimens of most of these languages. and it is possible to give fairly good. accounts of them, even if we do not know how many people speak them.

The influence of the ancient language of the Munda type is not so prominent in these languages as in those of the pronominalized group. There are nevertheless distinct traces of its previous importance, and we may assume with considerable probability that here we have a case of the old influence receding before that of Tibetan and of the Bodo languages spoken immediately to the East. We appear to have a clear example of this in Sunwar. In Hodgson's days it was a pronominalized language, but, if the specimens received for the Survey are to be trusted, it is so no longer. Hodgson's Essay was written in 1847, so that, allowing for the date when the specimens for the Survey were received, this change took place in little more than half a century.

As we know how rapidly Tibeto-Burman languages which have no literature to act as a conservative influence do change, this short period need not surprise us, and it is pretty certain that in all these languages the Munda characteristics were much stronger two or three centuries ago than they are now. On the other hand we also see in these non-pronominalized languages links connecting them with the Bodo Group. Whether they are naturally inherent in the languages or have been borrowed from the neighbouring languages we do not know, but, either way, it is the presence of these links which cause the Himalayan languages to form the western limb of the letter Y alluded to on page 53. The head-quarters of Gurung, Murmi, Sunwar, Magari, and Newari are in Nepal, and most of the speakers recorded for the Survey were found in Darjiling and the neighbourhood, where they formed an overflow from that country. Elsewhere in British India the speakers were chiefly found in Gorkha regiments. Only one of them, Newari, has any literature.

Before the Gorkha invasion the Newars were the ruling race of the country, and the name of the tribe is only another form of the word ` Nepal.' Newari was thus the state language of the country until the overthrow of the Newar dynasty in 1769. Buddhism was introduced into Nepal at a very early date, and, though Sanskrit accompanied it as the language of sacred books, Newari also soon became used for literary purposes. Most Newar books are commentaries on, or translations of, Sanskrit Buddhist works current in Nepal, but from the fourteenth century inscriptions in the language began to appear, ahd we have other survivals in the shape of indigenous dictionaries, grammars, and dramatic works with stage directions in Newari. The oldest Newari book with which we are acquainted was written in the 14th century, and is a historical account of the chief events in Nepal from A.D. 1056 to 1388. The language has an alphabet of its own and has received some study from Russian and German scholars, but the only Englishman who has examined it was Hodgson, and even he did not give it any special attention.

Another interesting language of this group is Rong or, as the Nepalese nickname it, Lepcha.. It is t he principal language of Sikkim, and has an alphabet of its own and a literuture which is said to consist mainly of works on Buddhist theology and connected subjects. As it is spoken within easy rooch of Darjilillg it ho.s nttmcwl the attention of English scholars, and has been provided with a gl'8omIDllof Ilnd dictionary written on European lines.

In the Pronominalized group the influence of the ancient munda language is Himalayan dialects far more apparent. In all of them we notice the characteristic idiom of suffixing personal pronouns to the verb to indicate not only the subject but also, often, the direct and indirect objects. When a Limbu wishes to say ` I strike him,' he turns both the ` I' and the ` him' into suffixes added to the verb. ` Strike' is hip , ` him' is -tu , and ` I' is -ng , so he says hiptung, which it will be remembered is exactly parallel to the Santali example given on page 37. Some of the languages of this group follow the Munda system of courting the higher numbers in twenties. Only two follow the Tibetan system of counting by tens, and the rest have embarrassed comparative philology by borrowing the Indo-Aryan numerals. In Tibetan and the languages allied to it there is a complicated system for expressing pronouns. But the various forms are due to the exigencies of etiquette, and each implies a different degree of politeness, just as in many other oriental languages we hear such expressions as ` this poor slave' used instead of an uncompromisingly egotistical ` I.'

But in these pronomillalized languages, thOugh there• is great variation of pronominal .l forms. this is based on au altogether different principle. Exactly as• in munda, there are three forms indicating number,-a singular, a dual, and a plurall,-for each person, and for the first person we have even greater diversity, there being separate duals for • I and thou,' and < I aud he: and plu.ra.ls for • I and you,' and • I and they:

In some of the Western dialects we even find what might almost be called instances of borrowing of munda words, and a relic of munda or Mon-Khmer pronunciation in the checked final consonants which have been describe on page 37 and 48.

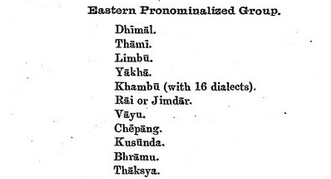

As stated above, these pronominalized languages fall into two groups, an Eastern and a. Western, which, So far a.s the materials available show, are separated from each other by a comparatively wide extent of country. The eastern group is confined to Eastem Nepal and the neighbourhood,-the so-called' kirant 1 country, owing to which they were appropriately named by Hodgson, 'the Kiranti Dialects.' As they all inhabit this tract figures are availa.ble for only flo few of them, and these refer only to settlers in Darjiling and thereabouts aud in no way iudicate the true numbers of the speakers of

these forms of speech. I therefore omit all figures in the list given on t he margin. Those curious in the matter can refer to the incomplete figures given in Appendix I (p. 392) ..

All these languages have been descrilJed by Hodgson, some very briefly, and others,---especially Dhimal, Bbhing (a Khambu dialect), alld Vayn,-at considerable length. LimbO. has 1\ full modern. grammar from the pen of Colonel Senior, but regarding the rest, practically nothing is known beyond the matermls collected by Hodgson and the subsequent informatioll collected for the Linguistic Survey. We know more about the Western Group of the pronominalized languages, as they a.re• all spoken in British. India. They possess all the munda characteristics that distinguish the Eastern Group, and it is

Here in kanauri and a nebighbouring dialect that we find the

languages is the Kana.uri (also written kanawari) spoken in kanawar ,sixty or seventy miles north- east shimla.It has receive some study,and has been given a grammer a vocabulary written by Europeans or compiled under there encouragement. Parts of the Bible have also been translate in to it.Kanashi is a curious

lonely language spoken in an isolated glen in Kulu, to the north-west of Kanauri, with which it has many points of resemblance. Being surrounded on all sides by speakers of Kului, anIndo-Aryan language, it has naturally borrowed from it a portion of its vocabulary, but the character of the language as a whole clearly points to a connexion with Kanauri. Manchati,Chamba Lahuli, Bunan, and Rangloi are spoken still farther to the north-west in the mountainous country of Lahul, Chamba, and Kangra. They have received attention from the Ladakhmissionaries, and gospels have been translated into Manchati and Bunan. The remaining languages of this group are spoken a long way to the east, in the mountain ranges of the north of Kumaun. Nothing is known of them except what is recorded in the Survey, and that is but little ; but, with one exception, it is sufficient to show that they belong to this group. The exception is Janggali, of which the Survey failed to obtain any satisfactory specimens. The name indicates the wildness of its forest speakers, and all that we can say with certainty is that it is a member of the Tibeto-Burman sub-family. It has been classed with the others, for the present, merely on account of its geographical positron.

The above remarks conculude our survey of t he Himala.yan Tibeto-Blurnlau dialects. All previously pointed out, the indica.tionll of the a.ncient munda inftuellce on these forms of speech is a matter of the greatest interest. It connects languages Is spoken in Lahul, J Chamba, and Kaniwar with the munda languages of Central India and through t them, with the Khasi spoken in Assam. and with the Mon-Khmer languages of Further India.

These last lead us On to the tongues of Indonesia. and Polynesia till we arrive at Easter

island. Roughly speaking, we find this Austric Fa.mily of languages extending from

s0° is east longitude to 1100° west longitude. a total of 170 degrees longitude.or very nearly half wa.y round the world. Excepting the Indo-European (which has in modern times spread from Europe to America.) it is the most widely extended of any of the language families of the earth.

North Assam. Branch

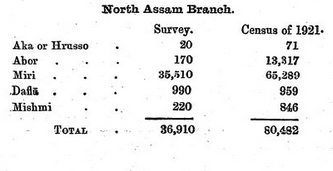

In describing the progress of the migrations of the Tibeto-Burman tribes, I have stated that, after the Tibetan branch had entered Tibet along the course of the Sanpo, some of its members crossed the Himalaya and appeared on the southern slope of that range. Of these, the most eastern are the inhabitants of Bhutan and Towang. East of them, extending fromTowang up to and beyond the extreme eastern corner of Assam, the hills north of the Brahmaputra are occupied by four tribes, the correct classification of whose languages is a matter of considerable doubt. These are, in order, going from west to east, the Akas, Angkas, or Hrusso ; the Daflas ; the Abor-Miris ; and the Mishmis. Most of these people live outside settledBritish territory. Our knowledge of them is therefore incomplete, and the figures shown on the margin in no way represent the real numbers of the speakers, but only those who were found in British territory. The Akas or Angkas, as they are called by their neighbours or Hrusso, as they call themselves, dwell in the hills north of Darrang, in a corner heween Towangand Assam. Of all the North Assam languages we know least about theirs. An attempt was made

to gain further information concerning it f01" the purposes of the Survey. but our oue

authority. the Aka. chief whose presence and help had been

secured, preferred the freedom of his native hills to philology, and disappeared before the work was finished, leaving our information tantalizingly incomplete. Robinson gave us a short vocabulary in 1841, Hesselmeyer a fuller one in 1868, and J. D. Anderson another in 1.896.1 The first differs altogether from the two latter, and is apparently really a corrupt Dafla. The Aka of Hesselmeyer and Anderson is certainly a Tibeto-Burman language, but it appears to have strange and peculiar phonetic laws which cause it to differ widely from the speech of any other language of the branch. Even the numerals and the pronouns have special forms, though, on the other hand, its vocabulary shows points of contact with Dafla, which do not seem to be due to borrowing. There are very few of the tribe, or of the Daflas in British territory. East of the Akas lie the Daflas, east of them the Miris, and east of them, on both sides of the Dihang river, the Abors.

Tbe Miris and th.e Abors speak the same language, with only dialectic variations,and t his is closely connected with Dafla. We know a good deal about Abor-Miri andDafla.

Robinson gave us grammars of both in the middle of the last century, and, to omit mention of less important notices, in later times Mr. Needham has given us a grammar and Mr. J. H. Lorrain a dictionary of the former, and Mr. Hamilton a grammar of the latter. We have seen that Aka and Dafla have points of contact in vocabulary, and at the other end of the chain Abor shows signs of affinity to the nearest form of the Mishmi language.

The Mishmis, who inhabit the hills north of Sadiya, are divided into four tribes, speaking three distinct dialects. The most western are the

Midu (or, as Robinson wrote, Nedu) or Chulikata Mishmis, who occupy the valley of the Dihang with the adjoining hills, and, to their east, the Mithun or Bebejiya (outcaste) Mishmis. These appear to speak the same dialect, or language, but about it we know hardly anything. We have only an imperfect vocabulary collected by Sir George Campbell. Even the indefatigable Robinson failed to get specimens of it. All that he can say is ` they speak a language peculiar to themselves, yet bearing some affinity to that spoken by their neighbours the Abors and Miris.' Bast of the Bebejiyas lie the

Taying or Digaru Mishmis, beyond the Digaru river. The Miju Mishmis are still further east, towards the Lama, valley of Dzayul, a sub-prefecture of Lhassa. Robinson has given us grammars and vocabularies of both of these, and Mr.Needham has also-written a Digaru vocabulary. The two dialects, or languages, are very different. The north assam branch of tibeto burman tongues is,it must be confessed a rather haphazard collection of the languages group on geographical rather on philological principles.our one certain conclution a negative that they can be class neither as Tibeto Himaliyan,nor as Assam Burmes,though they are conncted with both. They territory is a kind of back water over which various waves of Tibato burman immigration have swept,each leaving its record in the speech of the inhabitants .they all show point of agreement with one or other of the two remaining branches tibeto Burman .

speech, and, on the whole, they can be described as links which connect the TibetoHimalayan languages with the Assam-Burmese Bodo, Naga, Kuki-Chin, and Kachin.

Assam Burmese branch

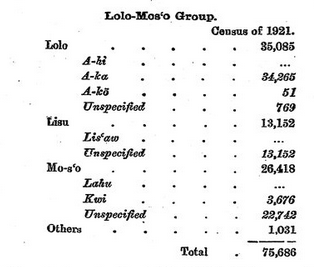

The probable race history of the tribes which employ the forms of speech belonging to the Assam-Burmese branch of the Tibeto-Burman languages has been glanced at in the preceding pages, and more details will ho given further on. This branch is further divided into the following groups : -- the Bodo, the Naga, the Kachin, the Kuki-Chin, the Burma, theLolo-Mos`o and the Sak or Lui. Of these the only groups that have been examined each as a whole in this Survey are the Bodo and the Naga. The Kachin, the Kuki-Chin, the Sak, and the Burma have been partly examined, as some of the languages belonging to them fell within the area of its operations, but by far the greater number of the languages of these four groups belong to Burma, and have not been touched by this Survey at all. Finally, the Survey has not touched any languages at all of the Lolo-Mos`o group.

The gaps left by this Survey will be filled up in due course by the proposed Linguistic Survey of Burma, and, pending its completion, I do not propose, so far as the languages of Burma are concerned, to do more than refer very briefly to them, adopting so far as may be the classification authorized by our very incomplete knowledge. It is quite possible that this classification may have to be seriously altered when the Burma researches are completed. For Bodo and Naga and for some of the Kuki-Chin languages, we are on firmer ground, and. I shall enter into the subject in greater detail. As regards all these groups, we may say that according to our present knowledge, the Bodo and Naga groups are those most closely connected with theTibeto-Himalayan languages, while the Kuki-Chin and Burma groups display more independent characteristics. Between these two extremes lie the Kachin and Lolo-Mos`o groups, the former being more nearly related to Kuki-Chin and the latter to Burmese. The Sak (Lui) group requires separate consideration, and seems to represent the outcome of one of the earliest Tibeto-Burman swarms.

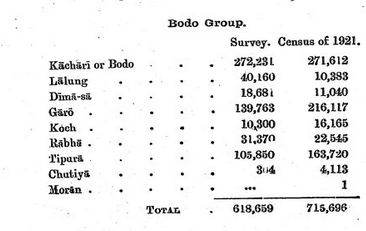

The group of tribes known as Bodo or Bara forms the most numerous and important section of th non-Aryan tribes of the Province of Assam. Linguistic evidence shows that at one time they extended over the whole of the present province west of Manipur and the Naga Hills, excepting only the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, which are inhabited by people speakingKhasi, a language of a different family, -- the Austro-Asiatic. To the north of the Khasi Hills they occupy the whole, or nearly the whole, of thee Brahmaputra Valley. To the west they have made the Garo Hills their own. To the south

they spread over the plains of cachar and, further, over the present State of Hill Tippera. On tbe east their: sphere of influence wa.s bounded by Ma.nipur and the wild tribes of the Nagao Hills. .Between the latter and the Kha.si Hills an important tribe of them were settled in the hills of North Cachar. One branch of the family, popularly known as the Koch, extended their power to far wider limits, and overran the whole of northern Bengal at least as far west as Purnea.

During the co'urse of centuries the members of the Bodo family have suffenrl much from externa.i pressure. From the east, in the year 1228 A.D. there begain the incursion of the Ahoms, a Tai race, who occupied the Bmhmaputra Valley, and ruled it for centuries till we annexed it, so that, in tha.t neighbourhood, we know of powerful KOch kingdoms only in Western Assam and in Cooch, or KOch, Bihar. To the east the Bodo t ribeS sank into insignificance, and, except where the mountainous nature of their homes has enabled them to maintain their independence, their members can now only be identified in communities of a. few hundreds each.

The Bodo country was also invaded from the south, .and this within the last two centuries. Pressed: forwa.rd by the.ir co-tribesmen beyond them, Kuki hordes left the LUshai and Chin Hills and migrated north, settling in Manipur, the Cachar plains, and more especially in the hill country of North Cachar, where the population is now mixed, partly Bodo and partly Kuki.

But the most important invasion Was that of Aryan culture from the west. With its language, it has occupied the plains of Dacca, Sylhet, and Cachar, so tha,t the Bodos of the Garo Hills are now sepated from their kinsmen of Hill Tippera. by a wide tract filled with a. population -speaking an Aryan language. So, too, with the valley of t he Brahmaputra. It is now almost completely Aryanized, and the old Bodo languages are gradually dying out. The ancient kingdom of Cooch Bihar now claims Bengali as it:S language, the old forms of speech surviving only in a few isolated tracts. In Kamrup and Goa.lpam. the former head-qua.rters of t he kingdom of Kima.rupa.. the spenkers of the Aryan Assamese and Eengali are counted by hundreds, while those of Bodo are counted By tens. The very name Koch has lost its original significance, and has now come to mean a Bodo who has become so far Hinduized tha,t he has a.bandoned his proper tongue and is part.ieular as to what .he eats. Na.y, many of those Bodos who still adhere to their old form of speech a.re trilingual. Numbers of them can speak Assamese, and in addition to this they commonly employ, not only 'their own pure racy agglutinative tongue, but also a cmions compound mongrel made up of a. Bodo vo1cabu.Iary expressed in the altogether alienidiom of Assamese.

I have said above that the word" Koch" has lost its original mea.ning, and now signifies a Hinduized Bodo. There ill, however, in t he Madhupur Jungle on the borders of Dacca. and Mymensillgh, in the Garo Hills, and the neighbouring districts of the Assam Valley, a body of people, known as Pani, i .e. Little, Koch, which still speaks It language of the Bodo Group. It iti nevertheless doubtful if they are Koches at all. According to some authorities t hey are Ga.ros who have never got beyond an impelfect stage .of conversion to Hinduism, involving merely the abstinence from beef. It has-been conjectured that they assumed this name of 'Litt l.e', or • Inferior' Koch by !way of propitiating the thoroughly Hindui1.ed KOch power which was predominant on ~there borders. If the specimens of their language

which I have seen are correct, it is a mongrel Garo largely mixed with. Assamese, and is the only form of speech known at the present day by the name of Koch. The traditions of the speakers do not, however, connect their tribe with the Garos. They believe thaf they came from the north-west, i.e., where the Koch kings formerly ruled, and they quite easily represent a tribe which had migrated from there to their present seats. The true Koches are now, at any rate, represented by the Kacharis, who inhabit Nowgong, Kamrup, Goalpara, Cooch Bihar, and the neighbouring country. Towards the east of this tract they call themselves Bara, usually mispronounced " Bodo," and have given this name to the whole group of languages of which their tongue is a member. Towards the wrest they are calledMeches, but everywhere their speech is the same, with a few local peculiarities.

Their language is a fairly rich one, and is remarkable for the great ease with which roots can be compounded together, so as to express the most complex idea in a single " portmanteau " word. For instance, the sentence " go, and. take, and see, and observe carefully " is indicated by a single word in Kachari. Of all the languages of the group it is the most phonetically developed, and here and there shows signs of the commencement of that true inflexion which is strange to most agglutinative languages. Another interesting fact is that in it we see going on before our eyes that process of phonetic attrition which, in all the languages of the family, has turned dissyllables into monosyllables, and has created that characteristic isolating appearance of all Indo-Chinese tongues.

To take an example : -- the word sa means ` person,' and the word fi is a causal prefix. Hence the compound fi-sa means ` a made person,' i.e. ` a child,' for the Tibeto-Burman mind cannot grasp the abstract idea which we connote by the word ` child,' and can think of a child only in reference to its father, the person who made it. But here accent comes in. It is put on the second word of the compound, so that the iof fi is scarcely audible, and we get fisa . This accounts for the origin of the word for ` child' in cognate languages. It is always a monosyllable, fsa , bsa , or something of the sort. Weshould never have known the real meaning of this monosyllable had we not Kachari for our guide. Nay, Kachari itself makes secondary monosyllables in this way. For instance, ranmeans ` to be dry,' but fran , which we now know to be contracted from fi-ran , means ` to make dry.'

Bodo is a language which is fairly well-known.' Besides school-books, we have for the standard Bodo dialect a. grammar by Endle arid an excellent collootioll of folktales:! by Andcrson, while Skrefsmd has given us a grammar of Mech.

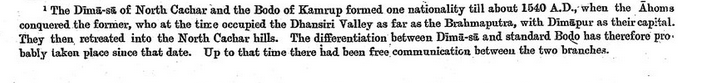

Closely connected with Kachari is the Lalung spoken in south-west Nowgong and the neighbourhood. It forms a link between it and Dima-sa. The last is the bodo language of the North Cachar. The name of the country in which it is spoken has led to its. being called ` Hills Kichari,' but this has the disadvantage of inducing the belief that it and the ` PlainsKachari' of Kamrup are different dialects of the same language1. Really these two are not so nearly connected as French and Spanish.

They both belong to the same linguistic group, and both, no doubt, have a North Cachar. The name of the country in which it is spoken has led to its. being called ` Hills Kichari,' but this has the disadvantage of inducing the belief that it and the ` PlainsKachari' of Kamrup are different dialects of the same language1. Really these two are not so nearly connected as French and Spanish. They both belong to the same linguistic group, and both, no doubt, have a

The name of the country in which it is spoken has led to its. being called ` Hills Kichari,' but this has the disadvantage of inducing the belief that it and the ` PlainsKachari' of Kamrup are different dialects of the same language1. Really these two are not so nearly connected as French and Spanish. They both belong to the same linguistic group, and both, no doubt, have a

common ancestor, but, at the present day, they are quite distinct forms of speech, and it is best to call Hills Kachari by the title which its speakers give to themselves, Dima-sa. Since it was described in the Survey, it has been given a grammar and vocabulary by Mr. Duudas. It has a dialect of its own spoken in south Nowgong called Hojai.

Going stil futher asm valley we find the most eastern of bodo languages,the chutiya which is fast

dying out. It is spoken only by a few Deoris, who form the priestly caste of the Chutiya tribe. They have preserved, in the midst of a number of alien races, the language, religion, and customs which they brought about a hundred years ago from, the country east of Sadiya, and which, we may presume, have descended to them with comparatively little change from a period anterior to the Ahom invasion of Assam. Their present seats are on the Majuli Island in Sibsagar, and on the Dikrang River in north Lakhimpur.

Of all the languages of the Bodogroup, owing no doubt to its religious associations, it appears to have preserved the oldest characteristics, and to approach most nearly the original form of speech from which they are all derived. It and Kachari represent the two extremes, the least developed and the most developed of the group. Like the latter, it exhibits the remarkable. facility for forming compound verbs to which attention has already been drawn. This is probably a characteristic of all the dialects of the Bodo group, but it is only these two which have been thoroughly studied, so that we cannot as yet be certain about the others.

Returning to western Assam, we have next to consider Garo, or, as its speakers call it, Mande Kusik, the language of men. Its proper home is the Garo Hills, but its speakers have overflowed into the plains at their feet, and have even crossed the Brahmaputra into Cooch Bihar and Jalpaiguri. Garo, in. its standard dialect, has received some literary cultivation at the hands of local missionaries, and, besides possessing a version of the Bible, has a printed dictionary, school books, religious and other works. Ithas a number of dialects which bear a strong resemblance to each other, though to a foreigner learning to converse with the natives the differences are striking enough.

That known asAtong or Kuchu presents the greatest variations, and Garos from, other parts of the Gayo Hills can make themselves fairly well understood wherever they go except in the Atongcountry. It is spoken in the lower Someswari Valley which lies south-east of the Garo Hills, and in the north-east of the District of Mymensingh. It appears to approach most nearly the original language from which the various dialects are derived, for we meet typical Atong peculiarities in the most widely separated localities, where Gsro, in a more or less corrupt form, is spoken. A language closely connected with

Garo is Rabha, which has most speakers in the District of Goalpara but which is dying out. Rabha seems to be a Hindu name for the tribe, and many men so called are pure Kacharis.At one time they formed the fighting clan of the Bodo family, and members of it joined the three Assam regiments before they took to recruiting Gorkhas.

The remaining important language of the Bodo Group is Tipura. Its home is the State of Hill Tippersa and the adjoining portion of the Chitta gong Hill Tracts, but speakers of it are also found in Dacca, Sylhet, and Cachar The Chittagong Hill Tracts people call it Mrung. It shows points of connexion with both Dima-sa andGaro, and generally has all the characteristics of the group in which it is included. An interesting point is that the word for ` man' is barak , which is almost identical with the name Bara by which the Kacharis of Kamrup and the neighbourhood call themselves.

To complete the survey of this group, we may mention Moran, a language which is believedd to be now extinct. The Morans were the first tribe conquered by the Ahoms when they entered Assam from over the Patkoi. They became the Gibeonites of their vanquishers, being employed by them as carriers of firewood, and are still found in Sibsagar and Lakhimpur. Their language belonged to the Bodo group, but they have nearly all abandoned it in favour of Assamese.

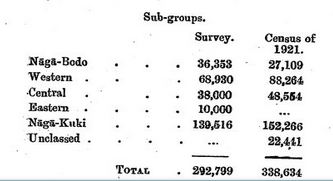

While the number of speakers of languages belonging to the Naga Group is less than half that of hose whose mother speech is Bodo, the number Of Naga languages is more than four times as many.The extra odenary, differnces of language ,not merely the hill country between the patqkoi range on the east, the jantia the hill on the west Bramaputra valley on the north and Manipur on the south ,render it one the most interesting for investigation by philologist . The asam valley proper is bounded south by ramges of hills separated it from

Sylhet and Cachar. At its western end these hills are comparatively low, and under the name of the Garo Hills are inhabited by a people speaking a language of the Bodo Group. Aswe go west they become the Khasi and Jaintia Hills, with summits rising more than six thousand feet above the level of the sea. Then we have a drop into the valleys of the Kapili and the Dhansiri, a country of low hills forming the subdivision of North Cachar. Further east, the general level of the tract rapidly rises up to the Patkoi, including the south of theNowgong, Sibsagar, and. Lakhimpur districts, the whole of the Naga Hills and the north of the State of Manipur.

Here we have a confused mass of mountains, some of them rising to nine or ten thousand, feet, which, as we go eastwards, become ranges running north and south, connected with the Himalaya through the Patkoi and the hills beyond, and extending southwards, through Manipur and the Lushai Hills, until they terminate in the sea at Cape Negrais. It is in this country, between North Cachar and the Patkoi, that the Naga languages are mainly spoken. The inhospitable nature of the land and the ferocity of the inhabitants have combined to foster this diversity of speech. Where communication is so difficult, intercourse with neighbouring tribes is rare, and, in former times, when heads were collected as eagerly as philatelists collect stays and no girl would marry a young fellow who could not display an adequate store of specimens, if a meeting with a stranger did take place, the conversation was sure to be more or less one-sided. Under such circumstances, monosyllabic languages, such as those of the Nagas, with no literature, with a floating pronunciation, with a system of taboo which is ever and anon prohibiting the further use of certain words, and with a number of loosely used prefixes and suffixes to supply the ordinary needs of grammar, are bound to change very rapidly and quite independently of each other. Cases are on record in which Between the Bodo and the Naga languages, there is an intermediate sub-group belonging in the main to the latter, but though in the main it is Naga. Kabui and Khoirao belong to north Manipur. As for the former all that was known about it previous to the Survey was a short vocabulary compiled by Major McCulloch in the middle of the last century. About Khoirao nothing was known till the Survey took it in hand.

The Survey figures for these two languages were very rough estimates, with no census figures on which they could be based. Since they were recorded, these tribes have fallen within the net of two regular censuses, and the figures shown for 1921 should be taken as more accurate than those given by the Survey. possessing distinct points of contact with the former.2 Empeo is the best known of these, as we have a grammar and a vocabulary of it by Mr. Soppitt. It is spoken in North Cachar and in the western Naga Hills, and it shows points of contact not only with Bodo but also with Kuki forms of speech, Turning to the Naga languages proper, we find them falls naturally into three sub groups, a western, a central, and an eastern. Of the western languages, the most important is Angami, with its two dialects, Tengima, and Chakroma, and numerous sub^ dialects of which the principal are Dzuna, Kehena, and Nali. A good deal is known about Tengima.

Beginning in the year 1850, Hodgson, Brown, Stowart, and Butler. all have given us vocabularies, and the descriptions of the tribe by the last two are classics. We have a grammar written by McCabe in the year 1887 and a phrase-book by Mr. Rivenburg in 1905, the latter having appeared subsequently to the Survey account. Then there are the admirable accounts of the language and of the habits and customs of the tribe from the pen of Mr. A. W.Davis, which appeared in the Assam Census Report of 1891, and which have been partly reprinted in Volume III, Part ii of this Survey. Finally in 1921 we have Mr. J. H. Hutton's " The Angami Nagas," which supersedes all previous accounts of the tribe, and on pp. 291ff. of which all our previous knowledge regarding its language has been excellently summarized. To the east of the Angamis are the Kezhamas, to whose north again lie the barbarous and savage semas .North of the Augamis and west of the Semas are the Rengmas. Until the aceount of this Survey was published nothing whatever was known to outsiders about the Kezhama language, and we had only short and incomplete lists o f a few words each of Sema

and Rengma, but since then Mr. Hutton has given us a Sema grammar and vocabulary. The Rengmas call themselves by the name of Unza, which is really the name of one of the two dialects of the language. It may be added that about half a century ago, a number of Rengmas were driven out of their proper home by the constant attacks of neighbouring tribes, and settled on a range of hills lying between the Mikir Hills in the Nowgong District and the forests of the Dhansiri. This portion of the tribe has lost most of its savage customs, and has to some extent taken to the habits of the people of the plains, while the others retain their primitive simplicity. The most characteristic feature which distinguishes these Western Nagalanguages from those of the Central Sub-Group is that in them the negative particle follows the word that it negatives, whereas in the Central Sub-Group it precedes it.

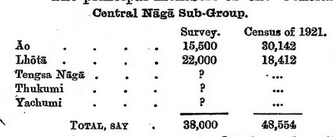

The principal members of the Central Sub-Group of the Naga languages are Ao And lhota.Minor members are tengsa,thukumi and yachumi.We have excellent grammers and vocabalaris of both Ao and lhota prepared by the local missioners .The former is well known and has often been written the literature concerning it is not always easy to find,as it has been described under atleast nine different names,some

appropriate enough, and others due to misapprehension. As an instance of the latter, we may quote the name ` Assiringia.' This is the name of a village inhabited by a ` Naked Naga' tribe, the members of which speak an Eastern Nagalanguage. But Aos often, come down from their homes to the plains through this village, and are hence wrongly given its name by the Assamese. Other names for Ao are again taken from the names of passes through which they come to the plains.

Thus, those who come down through the Dop Duar Pass are called ` Dupdoria,' and those who come down by the Hatigor Duar Pass are called ` Hatigorria.' But these are names and nothing more and connote no distinction of tribe or dialect.Ao has two well-markeddialects, -- Chungli and Mongsen, -- anc is spoken in the north-east of the Naga Hills District. Bhï½®ta is spoken: south of Ao about the centre of the same district, where it abuts onSibsagar. Its speakers are generally known as Lhota or Tsontsu, but they called themselves Kyo, while they are known to the Assarese as Mklai. All these names are also used toindicate the language. Teagsa, Thukumi, and Yachnmi are spoken by tribes beyond the Dikhu, and outside settled British territory. Very little is known about them, but short vocabularies enable us to connect them with Ao and Lhota.

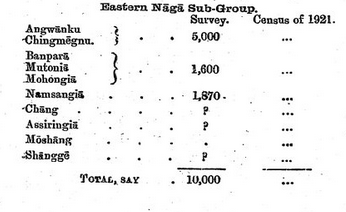

In the Eastern Naga Sub-Group are included the languages of all the other Naga tribes found in the tract east of the Ao country ,extending to the kachin country on the east and bounded on the south by the Patkoi range. Within these limits there are many different tribes ,some of them consisting only of a few villages un intelligible the one to the other .Within twenty miles of the country five or a six dialects are often to be found .the information that we process

they form a group of transition languages bridging over the gulf between the other Naga tongues and Kachin, the great language which lies to their east and regarding the languages spoken in this area is very scanty. but, so far ail our knowledge ° extend at present, a strong--affinity appears to exist among them a ll. There is also a great resemblance in the manners and customs of the Nagas of this trct. They nearly all expose their dead upon bamboo platforms. leaving the body to rot there. the skull being preserVed in the bone-house, which is to be found in nearly every village. In several of the tribes, the womeu go perfectly naked. III others the man. None of t hem bave been recorded in the census of1921.

The most important general point about these Eastern Naga forms of speech is t hat They form a group of transition languages bridging over the•

gu1f between the other Nagi tongues and Kachin. the great

language which lies tcdheir east and south. Another peculiarity which deserves notice is that at least four languages of the sub-group, -- Angwangku, Chingmegnu, Chang, and Namsangia, -- appear to have an organic conjugation of the verb. Eachtense seems to change according to the person of the subject, a state of affairs quite foreign to the other members of the Naga group and to Kachin, and almost foreign to the Bodogroup. The Namsangia verb (while not changing for number) has its three persons for each tense, just like Assamese or Bengali.

'Taking these Eastern Naga. languages from west to east, the first we meet are Angwangku or Tableng, and Chingmegnu or Tamlu. A rough estimate shows that they are spoken each by about 2,500 persons, naked savages who reside (sometimes both in tb,e same village) in t.he hills on both sides of the river Dikhu, before it enters the vallcy of the Brahmaputra. Like so many of these Tibet.o-Bunna-n tribes they call themselves by t heir word for • man ',- Kata. Tableng and Tamlu are the names given to them by the English after villages • in which they live. They call their own languages Angwangku. and Citingmegnu reapectivcly. Politically their main habitat is in).

The extreme north-east of the hills District. Beyound t he Dikhu River, outside settled British territory, we find.. a. language called, by the aos, Mojung, a.nd by its speakers; who u,re doubtfully estimated to beabout•6,500 -in number, Chang. The aus call all trans Dikhu Miri', a.nd hence the chang a.re often alluded to by that name, .which should be avoided, as leading to confusion with the altogether different Miris of the upper waters of the Subansiri. Nea.rly connected with ChAng is Banpara with one dialect called. MutoniA, which is spoken by tribes in western and central Sibsagar to the east of AngwAogku. We have. only & few lists of words belonging to t his language and its daialect. .

At t he eastern extremity of the same district lie the MohongiAs, is also called Borduarias and paniduarias brown writing in the year 1851 says that there languages is the same as namsangias, but this is not borne out by the only available specimen of the language, -- the first ten numerals published by Peal in 1872. Crossing the Sibsagar frontier, we find the Nagas of Lakhimpur, usually known by the name of Namsangias, but also called Jaipuria Nagas after the name of the village through which they mostly descend to the plains. We know more about their language than we do about any others of the Eastern Sub-Group, for Robinson published a grammar and vocabulary of it in the year 1849.

Owen, Hodgson, Peal, Sir George Campbell, and Butler have also given us more or less extended lists of words. Since then nothing seems to have been done regarding them. Indeed at the present day local Europeans seem to know much less about the languages of Sibsagar and Lakhimpur than did their predecessors of two generations ago. Even the Linguistic Survey has failed to obtain any additional information concerning them. The list of Eastern Naga languages is completed by a reference to

Moshang and Shangge, the languages of two tribes in the wild country south of the Patkoi. Further to the east and south we have the great Kachin country, the main language of which is Kachin or Singpho. It forms a link between the Nagaand Tibetan languages on the one side and Burmese on the other, and also leads, through the Meithei of Manipur, from Naga and Tibetan into the Kuki-Chin group.

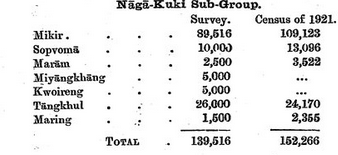

There is , moreover, another chain of Connexion between Nagi. and Kuki, the naga kuki Sub-Group of languages, which, on the other side, corresponds to the Nlagi-Bodo Sub-Group• already mentioned us leading from NagA into Bodo. The most important of these is Mikir, the headquarters of which are now ill the hills tha.t bear the same name in the Nowgong District of Aasum, and which is also spoken in slightly varying dialectic forms in South Ka.mrup, the Khasi &nd J aintia. Hills, north cachar and the naga hills.Small fragment of the tribe are also foun d else where and it ca.nnot• be doubted that in former timee the Mikir& occupied a. compam- tively large tract of country in the lowel" hills and joing low lands of the centel portions of the renge stretching from the Garo Hills to the Patkoi. .As elsewhere, the Mikirs call themselves• by their word for' man;' arleng

Their language has received some attention from the missionaries who work among them. We have a vocabulary and some short pamphlets written in it, and an admirable grammar with selected texts from the pen of the late Sir Charles Lyall. In Volume III, Part ii of the Survey I have classed Mikir as falling within the Naga-Bodo Sub-Group. The language has affinities with Bodo, but subsequent investigation has shown that it is much more closely connected with Kuki, and that it should be classed, as here, as belonging to the Naga-Kuki Sub-Group, in which it occupies a somewhat independent position.:

The remaining Naga-Kuki languages are found chiefly in the State of Manipur. As previously explained, there occurred a backwash from the south of Kuki-Chin tribes into this state, where they found Naga tribes already settled. We thus find here a great number of Kuki tribes, scattered over the country, each speaking a different language, and also a number ofNaga tribes, equally scattered, and all retaining languages of the Naga family in a more or less corrupted condition. The hills of north Manipur lie immediately to the south of the AngamiNaga country, and it is natural that here the Naga characteristics are retained most vigorously. It is in this locality that we find Sopvoma, used by the Nagas of the country road Mao

(whence their alternative name of ` Mao Nagas') on the Manipur Naga Hills frontier, about twenty miles south of Kohima. It is the language o f this sub-group which most nearly approaches the true western Naga speech, its closest relative being Kezhama. South of Mao lie the Marams, inhabiting one large village. The two tribes claim to have a common origin, but are at perpetua1 feud with each other. Both Brown and McCulloch have given us vocabularies of their language, which are sufficient to show that it is different from, but akin to, Sopvoma. In connexion with Maram, we may mention Miyangkhang or Mayangkhong classed by Damant with it and with Sopvoma. Nothing more is known about it.

Here also we may insert Kwoireng or Liyang, of which we have vocabularies by Brown and McCulloch. The tribe which speaks it inhabits the country north of Manipur town, and just south of the great Barail Range which forms the northwestern boundary of the State. Immediately to their south lie the Kabui Nagas, whose speech belongs to the Naga-Bodo sub-group, and their language is intermediate between that and Naga-Kuki. The forms taken by Kwoireng pronouns agree best with the latter, and therefore it is mentioned here, though the geographical position of its speakers would incline one to place it among the Naga-Bodo languages. They are a race possessed of some energy, which developes itself in trade with theAngamis and our frontier districts.

The large and important tribe of the Tangkhuls occupies the north-east of the State. They are sometimes called Luhupa or Luppa from the luhup , or curious helmet of cane worn by members of the northern sections of the tribe when going into battle. But such a name is misleading, as a similar headdress is worn by the Mao Nagas. The number of Tangkhul dialects is said to be very great, almost every village in the interior having its separate form of speech. We may select three as typical, -- Tangkhul proper (spoken in and near the village of Ukrul), Phadang, and Khangoi. Brown has given us three short vocabularies of Tangkhul, and the Linguistic Survey succeeded in obtaining sufficient specimens to compile a short grammar and vocabulary. Since the latter was published, the Rev. W. Pettigrew has compiled a formal Tangkhul grammar and vocabulary. The head-quarters of the tribe are at Ukrul, about forty miles to the north-east of Manipur town, and the same distance

to the south-east of the Mao tract. McCulloch has given us vocabularies of Bhadang and Khangoi. The former closely agrees with Tangkhul, while Khangoi has much more of a Kuki complexion. The latter leads us to Maring, spoken by a Naga tribe inhabiting a few small villages in the Hirok range of hills which separates Manipur from Upper Burma. There is also a small colony of them in the Manipur Valley, about 25 miles south of the capital of the State. It has two dialects, Khoibu1 and Maring proper, which are closely related to each other. It is the one of theNagaKuki languages which most nearly approaches the Kuki-Chin Group. The pronounm of the first person is the same as in Kuki. Both Brown and McCulloch have given us Maringvocabularies, and the Linguistic Survey has succeeded in collecting sufficient materials to compile a short grammar of the language.

The Ka.chin Group hardly concerns WI, as most members of the tribe that speaks the languages composing it dwell in Burma., and the various .forms of Kachin speech will be considered in, connection with

the linguistic Survey of Burma. There are, however, a few Kachin speakers found in

Assam. and they must be my excuse for the Following remarks which so far as Burma is concern must be taken as merely provisional pending the publication of the results of the Linguistic SUrYey, of .Burma. Another name for Kachin is, in Burma., Chingpaw, and, in Assam, Singpho. This, word, in its two different forms, means properly 'a. man of the Kachin t:ribe: and nence 'a. man' generally, The Kachins inha.bit the gretr.t tract of country including t he upper wa.ters of the Chindwin and of the Irrawaddy, which lies to the east. of Assam, a.nd t.o the north, north-east, and north-west of the more settled parts of Upper Burma.. During thelast t.hree qua.rlers of !;to century they have spread a long way. t.o the south into the NO,rthem Shan States and the districts of Bha.mo and Katha.

They would probably •have extended much funher. if we had not annexed Upper Burma. when we did; and indeed at. the present moment there are isolated Ka.chin villag.es far down in the Southern Shan . States and even beyond the Salwin River. Colonies of them appear t.o have entered Assa.m. where they are known as Singphos. something over a cent.ury ago, At any rate. t.heir la.nguage shows that they must have come into that. country after long contact with the' Burmans. Philology and t.he t.rad.itions of their race alike n point to the head-waters of t he Irrawaddy as their original home, from which they have gradually extended. mainly along the river courses, ousting their immigrant predecessors, the Burmese and the Sha.ns, The ltmguage of the Ka.chins varies gretr.tly over the large tract. of country that they occupy. They are essentially a people of the hills.

and almost every hill has. got its peculiar form 'of speech, We may, however. divide all the dialects into three classes-the northern. the Kaori. and that of the southern Kachins. The northen dialects leet, which we know best. in the form in which it is spoken by the Singph0se of Assam, ~ been described in the grammatical ketches of Logan~ Major afterward Brigadier Gcnernl) Macgregorand Mr, Need~am, Southern Ktwhiri. which is that spoken in •the• Bhamo district, is illustrated by those of Messrs. HertZ and Hanson. while the Kaori dialect, which is the langlJaoae of the Kaori Lepais. who inhabit the hills t.o the east ami the south-east of Bhamo, forms the basis of that written by Dr. Cushing. As regards the mutua.l relationship between Kachin and the other Tibeto~Burma.n languages it may be said t.o occupy a somewhat independent position, In, phonology it comes close ' to Tibetan; on the other hand. it iii also intimately relataition :naga and Kuki-Chin languages and to BurmeSe. Amo.ng the NiigA languages. It is nearest affinities are to thoSe that form the Eastern Sub-group. Of the Kuki-Chin languages. it shows. remarkable points, of resemblance to Meithei. Its relationship to Burmese has never been disputed.

The inquiries made during the progress of this Survey show._that Kachin. withont necessarily

being a transition language, forms a connecting link between' Tibetan. on the one

haud.•llolld Nigi. Meithei. and Burmese on the other.

The territory inhabited by the Kuki-Chin tribes extends from the Naga Hills, Cachar, and East Sylhet on the north, down to the Sando

way district of Burma in the south; from the Myittha River in the east, nearly to the Bay of Bengal on the west. It is almost entirely filled up by hills and mountain ridges, separated by deep valleys; we find the tribes also in the Valley of Manipur and in small settlements in the Cachar plains and Sylhet. Both the

Name Kuki' and • Chin , have been given to them by their neighbours

Kuki is an assamese or Bengali term apply ed generally all the hills tribes of these race in there vicinity while chin or khyeing is a Burmese word used to denote those leaving in the country between Burma ans assam .neither of these term is employ by the tribes them selves

The denomination 'Kuki-Chin' for this group of people.

and for the group of languages which they speak. is therefore purely conventional there being no indigenous name covering them all as whole. The tribal languages fall

into two main sub-groups. which we may conveniently ca.1l the ' Meithei' and chin We have already how it is probable that this stock-migrated. from the north or: north-eas t intO the Manipur Valley aad there settled, while another branch of the same stock proceeded further south and filled the Lushai and Chin Hilk Assuming thnt this represents the true facts of the na.tioual movement

Meithei represents the language of the original settlers in Manipur, and Chin that of the more southern migration. In these southern seats the language rapidly developed, partly by its own natural growth and partly by its contact with the Burmese. The development of Meithei, the language of Manipur, has, on the other hand, been slow and independent. TheManipuris are mentioned in the Shan chronicles so early as A.D. 777, and probably owing to the fact that it has in later times developed into a literary language, their present form of speech gives the impression of an archaic character. The language has an alphabet, said to have been introduced from Bengal about two centuries ago, and, written in this character, possesses a series of chronicles, carrying the history of the State as far back as the year 1432.

This character is mow practically obsolete, being ousted from current use by the Bengalialphabet. The language of the chronicles, too, is obsolete and is indeed intelligible only to professed scholars who have made it their business to study it. In Mr Hodson's book ` TheMeitheis ' there is given a long passage in this ancient dialect with the corresponding words in modern Meithei, and there can be no better example of the rapid changes which can be undergone by a Tibeto-Burman language in the course of a few centuries, we have here two different languages with hardly a word in common, and it is difficult to believe that one is the descendant of the other. So far as I am aware, no European has ever studied the archaic dialect, and, for scientific purposes, though it would be of little practical use, a grammar of it would be of considerable value ; for, between Burma and Tibet, Meithei is the only Tibeto-Burman language the history of which it would be possible to trace through at least two hundred years. For the modern language, we have now the Rev. W. Pettigrew's very full grammar, which has appeared since the Meithei section of the Survey saw the light. At the same time further information regarding this interesting language would be very welcome. We do not know if it has any dialects, and it is not improbable that further inquiries on this point would show that the apparent gulf between Meithei and the other KukiChin languages is actually fled up by intermediate forms of speech. At present, this much is certain, that the modern language has preserved many traces of a more ancient stage of phonetic development, and hence sometimes agrees more closely with Burmese, and even with Tibetan, than with the Kuki-Chin languages proper. On the other hand, in certain respects it shows points of common origin with the Naga languages and,

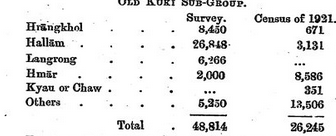

especially with Kachin, being a: connecting link between them and the southern, more developed, forms of speach. The Chin forms of speech include something like forty distinct languages which may be divided into the Northern Chin, the Central Chin, tho Old Ku1ci, a.nd the Southern Chin sub-groupe. The Old Kuki languages are most closely connected with the Centra.l Chin sub group, but. for Historical reason , it will be most convenient to consi4er them first of all. They arc

sixteen in number, most of them arc spoken by tribes now living in Manipur,now leaving in Manipur.

Cachar (especially the northern sub division , Sylhet and hill tipper who migrated to the presnt settlements at different period in these last centuries from their original homes in an about Lushai Land.

Only one tribe, the hmar, remained. in its original seat,in there language is at the present day much mixed with Lushei. The main migrntion to the north was indirectly due to the pressure exeroillOd by the Luslur.is. 'I'hese pressed. the thados from the south, who in their turn pressed the Old Kukis northward8 into their present homes. 'I'he ' thados now occupied the old home of the Old KukiB, but the

irrestistible progress of the Lushais northwards still continued, and the Thados had to

follow th0sQ whom they had disposses Od into almost the sa.me localities; a.nd as their a.rrivtll waa later, they. and their fellows booame popularly known as New Kukis, the earlier immigrants being known ft8 Old Knkis. .. Old Knki" connotess0 di8tinct group of cognate tribes and languages but •• New Kuki" connotes only one tribe, the thados out of five olosely ,.connected ones, the rest of whom still live in the Luahs and Chin Hills. It is therefore best ,to abandon the term " New Kuki," and to call the whole group of dve by the name of .. Northern Chins." The Lushais now occupy the old soat of the Old KukiB, and of,the subsequently, the Thid.os. After disp0ssessing the latter, theystill u.ttempted to progress north, and it was this which brought them tirst into hOfltile contact with the British power.

We thus see that there was a reflex wave of migration of the Kuki-Chin tribes, so that we find Manipur inhabited, not only by speakers of the early Meithei, but also by tribes whose native languages, once the same as an old form of that speech, have developed independently, and, owing to the want of a literature, much faster in a country far to the south.

The principal Old. Kiki languages are Hrangkhol1, with its dialect known as Bete, spoken in Hill Tippera and North Cachar, Hallam spoken in

Sylhet and Hill Tippera, and Langrong, also spoken in the latter State. We have a grammar of Hrangkhol by

Mr. Soppitt, but, till the Linguistic Survey, very little has been known about the others. No less than eleven2 languages are spoken by small Old. Kuki colonies in the State of Manipur. These are Aimol (Census figures, 387), Chiru (1,577), Kolren (600), Kom (2,855), Chote (264), Muntuk (nil), Karum (nil), Purum (1,132), Anal (3,065), Hiroi-Langang (744), and Vaiphei

(2,882). The Chiru and the Anal are mentioned in the Manipur chronicle as far back a the middle of the 16th century, and the Aimol make their first appearance therein in 1723. Regarding the others I have no information as to when they arrived. As already said, Hmar is still spoken in Lushai Land, the tribe having accepting lushai domenation and finally fur to the south, on the banks of the Koladyne, we find Chaw spoken by the descendants of some old Kuki slaves who were offered to a local pagoda by a pious queen of Arakan some three centuries ago.

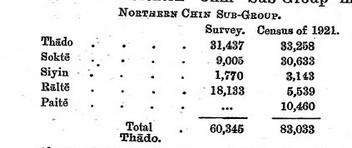

The northern chin sub group includes thado (with its dialects khonzai

Langtung, Jangshen, and Sairang), Sokte, Siyin, Ralte, and Paite. The Thados, who are sometimes, as explained above, called New Kukis, formerly lived in the Lushai and Chin Hills, where they had established themselves after having expelled the old Kuki Hrangkhol and Bete tribes. They were themselves gradually ousted by the Lushais from the former tract and settled down in Cachar and the Naga Hills some time between 1840 and 1850. About the middle of the 18th century the Thados of the Chin Hills were conquered by the Soktes and were driven north into the southern hills of Manipur, where they are now found and are locally known as Khongzais. There are now very few Thado villages left in the Chin Hills. TheSokte tribe, which includes the Soktes proper and the Kamhows (or, as the Burmese call them, the Kanhows) occupy the northern parts of the Chin Hills, and the Siyins the hills immediately to their east, round Fort White. These two last really below to Burma, and will be dealt with in the Burmese Linguistic Survey. They are mentioned here only to complete the tale of the Northern Chins.

The Raltes are principally found in the western parts of the Lushai Hills, but in modern times bodies of them have settled in Cachar, both in the plains and in the hills. The Paites are scattered all over the Lushai Hills, a few being found in almost every village. They have accepted the Dulien domination, but have retained their own language, which, however, like Ralte, is much mixed with Lushei

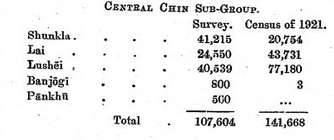

The Central Chin languages are Shunkla or Tashon, Lai, Lushei or Dulien, Banjogi and Pnkhu. These are all closely connected with the northern sub-group, but have a still greater affinity with the Old Kuki forms of speech. The Tashons, who call themselves Shunklas, dwell in the country south of that inhabited by the Siyins and Soktes, and properly fall within the bounds of the Linguistic Survey of Burma. They are mentioned here only for the sale of completing the list. They form a powerful tribe, and their country is the most thickly populated in the Chin Hills. There are several dialects of the language, and at present the only one of which we know more than the name is called Zahao or Yahow. Like the Shunklas, the Lais properly

belong to Burma, although there are colonies of them whose language falls within the purview of this Survey. The Lais inhabit the middle portion of the Chin Hills, their name being said to mean ` Central.' The Burmese call them ` Baungshe' from their fashion of wearing a knot of hair over the forehead. Several dialects of Lai are spoken by the surrounding tribes, and nearly all of them also understand the standard form of that speech. This is also the case with the Shunklas, so that Lai is an important language for the purposes of administration, and has been well illustrated in a grammar prepared by Major Newland. Lakher, one of the dialects, is spoken in the south of the Lushai Hills. Its speakers are called Zao or Zo by the Chins. They are an offshoot of the Tlan-tlang (or, as the Burmese officers say, Klang-klang) Lais, whom the British first met on the Arakan and Chittagong frontier under the name of Shendoos.

As Lai bids fair to become the general means of communication in the Chin Hills, so Lushei has become that of the Lushai Hills. This Lushei. tract has become the scene of various migrations, new tribes at different times pushing the preceding inhabitants westwards and northwards. The Lushais, who are now the prevailing race, seem to have begun to move forwards from the south-east in the early part of the ninteenth century. Between 1840 and 1850 they obtained final possession of the North Lushai Hills, having pressed the former possessors, the Thados, before them into Cachar. In 1840 they made a raid on a Thado village in that district, and for the first time came into contact with us and found their northward progress finally stopped. Our subsequent relations with them are a matter of history.

Their name is commonly spelt ` Lushai,' but the proper mode, which is employed when speaking of their language, is ` Lushei.' They usually call themselves ` Dulien' and their language ` Dulien Tong.' The latter has several dialects of which the best known is Ngente, spoken by a non-Lushai tribe in parts of the South Lushai Hills, in the villages round Demagiri, and in some of the western Howlong villages. Another is Fannai, spoken, also by a non-Lushai tribe, between the eastern border of the South Lushai Hills and the Koladyne. Standard Lushei is comparatively well known. Several grammars have been written of it, the most important being that of the pioneer missionaries, Messrs. Lorrain and Savidge, which is accompanied by a very full dictionary. Banjogi and Pankhu are two unimportant languages spoken in the Chittagong Hill

Tracts LuahCi is the only one of these three langua.ges for

which fairly aceura.te figures are available.

The languages classed as Southern Chin do not, save in two instances, fall within the scope of the Linguistic Survey of India. The two exceptions are Khynng or ShO a.nd

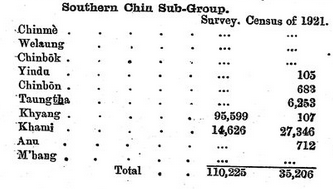

Kami, Khweymi, or Knmi. The language Of the khyange or khyange (the word is mearly the arakan pronouncation of the word chin) hardly concern us there main habitation is ther main country on both side of the arakan yoma in Burma but about a hundred of them are also found in the chittegong hill tracts ,and thus fall witin the present survey.the survey figures(95,599) given

on the margin are those of the Burma Census of 1891, but at that time all the languages of the Sub-Croup except Khami were included under the general name of ` Khyang.'

There language has receive some attention,

mars and vocabularies by Major Fryer and Mr. Houghton, besides word-lists by other writers. They are partially civilized and are hence sometimes known as ` Tame Chins.' They call themselves ` Sho.'

The Khamis, or as the Burmese nickname them ` Khweymis,' ` Dogs' tails', are found in the Chittagong Bill Tracts, and along the River Koladyne in Arakan. They used to live in the Chin Hills, and. came to their present seats only in the middle of the nineteenth century. We have several vocabularies of their language, and a short grammar published in 1866 by the Rev. L.Stilson. This language also properly belongs to Burma, and its inclusion in the Linguistic Survey of India is merely due to the presence of some of the speakers in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. All the other languages of this sub-group are confined to Burma, and will form subjects of the investigations of the Linguistic Survey of that Province. For the sake of provisional completeness I have given in the list in the above marginal note, the names which I have come across, but I cannot assert either that it is complete or even that the names given are correct. It is not as yet even certain that all the languages named are Tibeto-Burman. The Chinmes, who were formerly described as inhabiting the sources of the eastern Mon, and as a connecting link between the Laisand the Chinboks, have been lost sight of since 1901. A similar fate has befallen the welaung Chins, who were formerly described as inhabiting the villages at the head-waters of the Myittha River, and as being bounded on the north by the Lais and on the south by the Chinboks. These last named live in the hills from the Maw River down to the Sawchaung. They are bounded on the north by the Lais and the Welaungs, on the east by theBurmans, on the west by the tribes of the Arakan Yoma, and on the south by the Yindu Chins. The Yindus are found in the valleys of the salinchaung and the northern end of the Mon Valley. The Chinbons inhabit the southern end of the Monchaung and stretch across the Arakan Yoma into the valley of the Pichaung. All these localities, unless otherwise stated are in, or

near, the Pakokku District of Burma. In the same District are found the Taungthas. Anu is spoken in northern Arakan, and M'hang in Akyab. The last named is also reported fromKyaukpyu. This is not the place in which to explain the main points of differentiation which characterize the Kuki-Chin languages: The necessary particulars will be found in volume 3,part3 but i may draw attention peculiraty with admirably illustrates the nature of the tibeto burman construction.it is well known face none of these languages a proper verb.the words which function of our verb in reality in vourble nouns denoting a sate or an action they are for delt with ad nouns and forms corresponding to ore tenses are formed by adding post position,or are compounds the last part of which has the meaning for finishing beging extra .these is peculiarly evident in the chin languages.in most

of them the verbs are never conceived in the abstract, but are always pot into relationship with some other noun which, with us, would be the subject. This is effected in exactly to same way as with ordinary nouns, viz., by prefixing the possessive pronouns, so that the expression. ` my going' is used instead of 'I go.' Thus, in Lushei, when we want to say ` I am', we sayka ni , literally ` my being'; and when we want to say ` thou art,' we say i ni , ` thy being.'

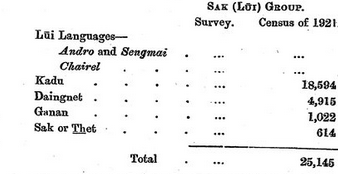

The Sak, or Lui, Group cannot be considered as definitely established till the Linguistic Survey of Burma is completed.

The Luis or Lois are a group of servile tribes found in the Manipur State, and are said both by the Meitheis and by their own traditions to be descendants of the antochthones of the country, who were dispossessed of their fertile lands by the tribes of the Meithei confederacy1. McCulloch, in his Accowtat of the Valley of Munnipore and of the Hill Tribes , gives vocabularies of three languages, -- Andro, Sengmai, and Chairei, -- spoken by Lui tribes, but no such were reported for the Linguistic Survey, and subsequent accounts have shown that they are now nearly extinct. Already in McCulloch's day (1859) they were in course of being superseded by the dominant Meithei. Andro and Sengmai are practically the same language, and they are closely connected with the Kadu mentioned below. Chairel is very different from these three, and I have been unable as yet satisfactorily to affiliate it to any other forms of Tibeto-Burman speech, although it manifestly belongs to that sub-family. Pending further information from the Burma side, I have temporarily put it together with the two other Lei languages, although I cannot suggest any relationship between it and them.

Kadu is spoken in the neighbouring Burma districts of Myitkyina, Katha, and upper chind win , and ganan in the last to of these.Ganan is merely a variant of Kadu, and its speakers as well as those of Kadu call themselves ` A-Sak.' This leads us on to Sajk or Thet, spoken far away, in the Akyab District, which is allied to Kadu. Mr. Taylor

tells us that, according to Burmese history, in early days the Saks inhabited the upper part of the Irrawaddy Valley. Some of these are supposed to have travelled from their original settlement in North Burma in a south-westerly direction into Arakan. He suggests that some of them may have passed on into Manipur and become the ancestors of the Andro andSengmai tribes. Another possible explanation is, however, that the original Kadu-Saks, while still in north Burma, spread also into Manipur, and that the Andro and Sengmai were left behind there, like the Kadus of Myitkyina and the neighbourhood, when the Saks migrated to the South-West. The facts that they were servile tribes, and that they were expropriated by the Meitheis, show that they must have been very early settlers there, and that they were found there by the Meitheis when they conquered the country.

Finally, Daingnet is the language, much corrupted by the Indo-Aryan Bengali; ot the descendants of sak prisoners of war from the Valley of the Lower chindwin, who were captured by King Mindi (If Arakan at the close of the thirteenth century and made to settle in the Akyah District1,

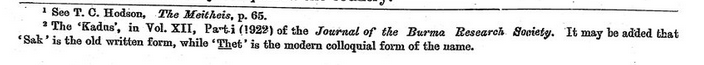

The remaining language of the Tibeto-Burman Sub-Family belong to B urma, and their conncideration must be left to the Burmese Linguistic Survey. Here, for the sake of completeness I shall give little mo~ than a. catalogue as accurate as our present knowledge permits.