Dupatta

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Dupatta

Dupatta: a statement of style

By Zahra Shahid Hussain

From the pristine white cotton dupattas of yore to flowing chiffons from France, this piece of garment has become more than just a cover and cultural more. Dupatta is both a fashion statement and an adornment

“Ooday baadal kay saye men lehraey gee, bul khaey gee jaisay nadia deewanee, chundria dhani,” sings Bilal Maqsood of Strings, in the words of poetess Zehra Nigah and we can immediately picture the green dupatta fluttering in the breeze under the shade of purple clouds, and see the rippling tie and dye effects of purple and green orhnis, chundris or dupattas.

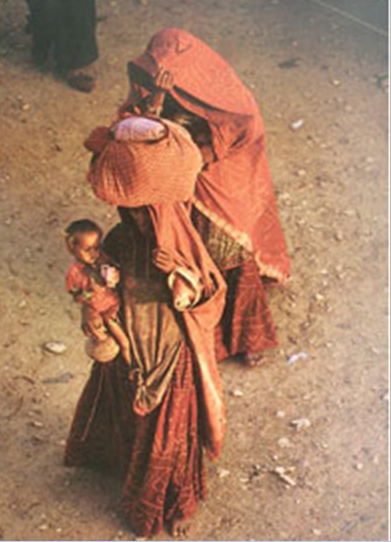

Dupatta is ubiquitous; it knows no hierarchy and is worn by girls and women of all ages, class and status. Princesses wear it as well as their maids. Dancing girls use it provocatively and women cover themselves with it during prayers. Young and old, wealthy and poor have worn it for centuries and continue to wear it. However, the only difference is in the material used and the embellishment, if any.

Dupattas are made of all varieties of fabrics, natural and man-made. They are made of coarse and loosely woven cottons and the finest muslins, of delicate chiffons and shimmering silks. They are woven using intricate weaving and colouring methods such as ikats, jamawars, jamdanis, etc., or embroidered with silks of many hues and gold and silver threads, beads, sequins, shells, spangles and more. The designs, techniques and methods are innumerable and modified and changed only according to the maker’s skills and the wearer’s fancy.

From the harsh and barren desert have come the most intricate and colourful fabric decorating and dyeing techniques from block printing to tie and dye and bandhinis. These dupattas are prepared in myriads of colours and then often starched and gathered into tiny pleats whilst held taut by toes to become chunna hua dupattas. These ripple and move to reveal the different colours with each movement.

The original kalamkari, sanganeri and Mughal designs amongst many others derived from far and wide and were brought to the subcontinent by waves of travellers and invaders. They have been very successfully replicated by the many dress designers in Pakistan, and subsequently by the various textile mills that now reproduce them in millions at a fraction of the original cost.

Along with its many designs and fabrics, dupatta has as many meanings and uses. It is as inextricably intertwined with our joys and sorrows, our celebrations and various rites of passage in our lives as it is with the clothes we wear. What began as a shoulder mantle or wrap for protection against the sun and cold soon found other uses as well.

As societies matured and concepts of property and ownership developed, male domination grew and women were also regarded as property and therefore had to be confined and denied access to other males. Dupatta, or a long piece of cloth to wrap round the head, face and body, was useful in allowing movement and at the same time concealed the body. Over the centuries, with the development of textile manufacturing and designing it also became part of the cultural and social life of its users.

There are different dupattas worn at different occasions, such as the various wedding ceremonies, from the yellow and green of the mayoon and mehndi, to the glorious red of the bridal dress. While on serious occasions such as funerals and religious gatherings, the more sober and unadorned shades such as white and black are preferred.

Dupattas are used in conservative societies as a shield of honour and protector of modesty. No woman would willingly remove it from her head and face. Its forceful removal is taken as the height of insult to the woman and her family. The dupatta has been worn for centuries in both Muslim and non-Muslim communities. It is used to denote reverence and covers the wearer during prayer time and solemn occasions, and as a form of hijab.

Since Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim state came into being, women have been wearing what they consider an appropriate according to their religious norms. However, over the years it has undergone many transformations and changes.

From the pristine white cotton dupattas of the early years to flowing chiffons from France, this piece of garment has become more than just a cover and cultural more. It became a fashion statement and an adornment. Till then it was used to cover the breasts and heads of women from the gaze of lustful men and ensure their modesty. Then came a veritable explosion of designs and colours.

Pierre Cardin came from Paris to design the uniform for the PIA air hostesses and suddenly all young and bold enough to emulate, were wearing slim flared pants and tailored scarf-like dupattas over form-fitting tunics.

France started production of silks and chiffons in the same designs and Pakistani women began to wear patterned chiffon dupattas with their matching silk outfits. The idea was taken up by local designers, and block printed outfits with beautifully patterned dupattas were in great demand.

Fabrics of all hues, colours and designs were being used. Designs which were considered ethnic and indigenous to their regions of origin became popular and fashionable all over the world and finding expression in dupattas worn by girls in cities and urban centres.

How did the dupatta originate? Where did it come from? What were its predecessors? These are some of the questions which come to mind. It is safe to assume that ever since our ancestors, the hunters and gatherers of food, discovered agriculture, gave up their nomadic existence and settled down in one place, their prime concerns were the production of adequate food and shelter and protection both from the elements and the environment and the dangers lurking therein.

Along with its many designs and fabrics, dupatta has as many meanings and uses. It is as inextricably intertwined with our joys and sorrows, our celebrations and various rites of passage in our lives as it is with the clothes we wear. What began as a shoulder mantle or wrap for protection against the sun and cold soon found other uses as well.

These early settlers soon discovered that fibre could be made from plants, trees and animal hair, and began the manufacture and use of cotton, wool, hemp and jute for their clothing and items of daily use, such as rugs and floor coverings. The first and most skilled of these were the people of the Indus Basin, our present-day Pakistan.

The textile traditions of these early settlers have their roots in the pre-historic communities of Neolithic farmers and herders who lived and traded in small settlements along the banks of the river Indus and its tributaries.

One of the most well known proofs of textiles from Mohenjo-Daro can be seen on a small stone sculpture of a man with a patterned cloth thrown over one shoulder --- known as the Priest King ---- dated about 2700BC. The pattern consists of circular designs and trefoils and the patterned cloth is either woven, embroidered or printed, difficult to say which, but evidently indicative of a well advanced textile tradition, one which favoured embellishment.

At the time of these excavations, spindles, probably used to wind weft thread when working on wooden looms, were also found at the site; and the presence of bronze needles also suggest that this Bronze Age civilisation embellished its woven cloth. From this evidence we can easily conclude that the people of the Indus Basin were at least two or three millennia more advanced in the production and use of cotton and dyes than the Europeans.

As most of the material for textiles was bio-degradable, it is unfortunate that in spite of this region being more advanced than other civilisations, very little actual evidence has been taken from excavation sites. There has, however, been enough to gauge that along with cotton, jute and wool, silk was also known to the early inhabitants of the Indus Basin.

The silk thread has been found inside copper beads and impressions on pottery and clay are clear indicators that silk was used if not manufactured. This means that silk was coming to the subcontinent from China where it originated. Other sources of indirect evidence and information are ancient Sanskrit and Buddhist texts which refer to the use of veils and textiles.

Ajrak, a traditional cloth of Sindh, dates back to this time and has remained almost unchanged except for the fact that chemical dyes are now substituted for natural ones. The making and printing of ajrak is an integral part of the culture of Sindh, and is immersed in its mystic and Sufi traditions. And it is the factor which has ensured its continuity and production.

Though initially, ajrak was worn by Muslim men on important ceremonial and religious occasions, its designs are now very popular and found in outfits and dupattas of women as well.

It is widely surmised that in spite of well-developed textile manufacturing techniques, garments and clothing in this region were largely unstitched and worn draped, tied and folded over the body, until the advent of the Muslims to the subcontinent. The warm and humid climate allowed the inhabitants the freedom of minimum clothing, and the rich fertile, easily cultivable land provided them with abundant sustenance and, consequently, the leisure to develop and enhance their skills and crafts.

The origins of dupatta can surely be found in the old unstitched garments such as the shawls made from wool and camel hair and the saris, lungis, and shoulder mantles made from muslin and cotton. It is most likely that the dupatta came to be known as such as unlike the saris, lungis, dhothis or sarong, both ‘pats’ or ends were left to flow freely, hence dupatta. In some communities amongst Muslims, they are also called izzat, synonymous with honour.

The women of these communities cannot be seen without their dupatta. In conservative societies, it offers mobility to women of a lower economic class. They can cover themselves and move out of the confines of their four walls. The wealthier women in older days could travel inside covered palanquins or carriages and afford to wear fine shimmering dupattas, used more for decoration and glamour than as a badge of honour.

The subcontinent is probably the only place on earth where the national dress is worn as a matter of course and has not been completely replaced by western garb. The dupatta is an integral part of the costume of the women of the subcontinent and an essential fashion accessory as well. It is an accessory that has been adopted by fashionable women in other parts of the world, too. One of the customs amongst women here, connected with dupatta, is the fact that exchange of dupattas between two friends is a declaration and seal of sisterhood. The uncovering of the veil to look at the face inside is symbolic reference to spiritual revelation and knowledge.

It is said that many centuries ago the wife of a mighty Chinese emperor was intrigued by the formation of cocoons by white worms in the mulberry trees of the imperial garden. Suddenly, one of the cocoons fell into the cup of hot tea she was drinking and began to unravel. Thrilled by the discovery, she immediately had more cocoons collected and unravelled by immersing them in hot water. The thread was then used to weave the most beautiful cloth seen so far.

The fabric was soft and smooth and shimmered with an unequalled and thus began the story of the charming cloth that is silk. The secret was jealously guarded, and the moths, worms and cocoons were more protected than the most valuable nuclear formula these days. Death was the punishment meted out to anyone attempting to take the technique out of China and it was only the cunning and duplicity of Christian missionary travellers that enabled them to smuggle a few cocoons out of China in hollowed out walking sticks, and the rest of the world also came to know of the glorious fabric.

The use of cotton, wool and silk fibres and the development of various styles of clothing in the earliest urban centres became the foundation of later textile traditions of the Indus Valley and South Asia.

Most of the garments continued to be made from unstitched cloth and the next stage of urbanism in the period came when long distance trade networks were established between China, Iran, Central Asia, Egypt and the Mediterranean. This led to cultural migration and the cross fertilisation of ideas, technologies and cultural styles. Ancient texts and excavation finds provide evidence of the use of many different types of fabrics, many of which are still in use.

Though the Indus Valley is the repository of the oldest and finest textile traditions, the stitched garment came with the Muslims around the 13th century. The unstitched fabric denoted purity and could be used in a variety of ways. Remnants of fibre and yarn have been found even at the site of Mehergarh, which is dated about 8000BC.

The romance of the dupatta must surely be attributed to the Mughals, as from being a practical form of comfort, protection and covering, it acquired a glamorous and decorative facet. Under the practice begun by Emperor Akbar, a patron of the arts and crafts, and encouraged and carried on by his descendants and the nobles of the court, the textiles of the subcontinent reached almost legendary levels of perfection. Muslins, so fine that they became invisible when wet and could not be seen by the naked eye, were woven on hand looms for the ladies of the royal household. A whole roll could pass easily through a lady’s ring. This fine art was brutally constrained by the British to negate competition for the mills in England.

It is said that when once Aurangzeb, the austere Mughal ruler, admonished his daughter Zaibunnissa on her revealing dress, she gently informed him that she was wearing eight layers of clothing. The Empress Nur Jehan was greatly instrumental in introducing various articles of clothing and embroideries to the already elaborate repertoire of clothing existing then in the court and the dupatta took on alluring and tantalising aspects.

Who can deny the deliciously teasing seduction of a sideways glance from kohl-laden eyes over the edge of a gossamer fine gold trimmed aanchal or peeping mischievously through a shimmering ghoongat? Many a film director has used the scene to their benefit.

Faiz Ahmad Faiz has also said: “Un ka aancal hai kay rukhsar ka perahen hay, kuch to hay jis say hoi jaatee hai chilman rangeen.”

The dupatta is omnipresent and also perennial. It has been around from time immemorial and taken on a multitude of hues and shades. The number of fabrics used to make dupattas has increased vastly through the ages, but the everlasting favourites will always be silk and cotton, and will remain that way.

Views of young women

It is a symbol of femininity; it signifies modesty; it enhances the beauty of the attire — it is a hindrance in the way of freedom of movement and signifies inequality between the genders: the youth of today seem to be greatly divided on how they perceive dupatta. They are also equally divided on how it should be worn, if at all.

Traditionally, dupatta is worn with its centre resting on the chest like a garland with both ends thrown loosely over each shoulder. Many a times, its one end is used to cover the head. While many stick to tradition, there are those who feel it is more fashionable to wear dupatta hanging from one shoulder or tightly clung around the neck. There are yet others who would rather be rid of the garment altogether – each group having its own reasons for the choice.

“I don’t see the point of wearing a dupatta,” says Sana, a 16-year-old student. “It is a hassle as it constantly slips of the shoulders. It is possible to look decent even without it,” she claims. Mariam, another young student, thinks differently. “Dupatta is a sign of modesty – a quality that our religion teaches us,” she says, “I have recently started to wear it over my head like a scarf and have noticed a considerable amount of difference in the way I see myself and the way others perceive me. I have started to feel more respectable now.”

There are many who feel strongly not only about wearing a dupatta but also about how it is worn. Kiran, a young working woman states, “It should not be worn at all, if all it’s going to do is hang around the side.” She, like many others, feels that those who do not wear dupatta in the traditional way make a mockery out of it.

However, there are still those who like to wear a dupatta merely for aesthetic reasons. “It looks pretty and colourful,” says an enthusiastic teenager, “Shalwar kameez looks so incomplete without it.” However, in spite of the strong inclination towards fashion, the cultural and modesty factor is still very prominent amongst many teenagers. Dupatta is also seen as a representation of culture and tradition. In fact, there is a recent trend of wearing a dupatta with western clothes like skirts and pants in order to give it a more ethnic touch.

The way young girls wear dupatta is usually a matter of personal choice. Having a very balanced view on the subject, Uzma, a 19-year-old student says, “While taking a dupatta is every woman’s prerogative, no woman should be forced to wear it or, for that matter, be criticised for her choice of wearing it in whichever way she pleases.” In either case, dupatta continues to be a very important part of most eastern dresses. — Raabia Hirani

The filmi dupatta

"Hawa mein urta jaye mera lal dupatta malmal ka, ho ji, ho ji" crooned a young Lata Mangeshkar for the movie Barsaat (1950), which was the maiden assignment for composers Shanker-Jaikeshan, who had a long and fruitful career in store. The song was not picturised on Nargis or debutante Nimmi, the two leading ladies of the movie, but on a starlet Vimla. And you know why the dupatta didn’t appear red on the screen? The answer is simple: the movie was in black-and-white.

About the same time, Noor Jehan starred in a Pakistani movie called Dupatta, produced and directed by her first husband, Shaukat Husain Rizvi. The film had a lilting score by Feroz Nizami. There was a song which referred to flying but it had nothing to do with Noor Jehan’s dupatta. It was just that the singing star wanted to fly like a kite. The song that I am referring to is Mein bunpatang ur jaon, hawa ke sang lehraon.

While on film songs, one may like to add that there have been a number of dupatta ditties, but with terms like orhni, chunri, chunarya and aancha. The most melodious was Lata’s number in Dulhan Eik Raat Ki – Mein ne rang li aaj chunarya sajna tore rang mein. Only composer Madan Mohan could have made it as mellifluous. On the other hand, the most impish number in the genre was Chor do aanchal zamana kya kahega, a duet by Kishore Kumar and Asha Bhosle. Then there was Mehnaz’s song Aei shokh hawa anchal na urra, from the Lahore film Aaj ka insaan, but Runa Laila, on the other hand, didn’t seem to be bothered about the breeze lifting her dupatta in the song Hawa aanchal urrati hai, urrane do, from the Karachi film Jhuk Gaya Aasman.

Punjabi films also had similar songs. In a rare duet that Melody Queen sang with Nazeer Baig (actor Nadeem), she tells him to stop holding her dupatta Mundya, dupatta chad mera.

The other Punjabi song that I can recall is Chunri kesari te gotey di dharyan (the chunri is saffron-coloured, while the borders are adorned with gota). A Poorbi folk song is interesting too. It says Koi jug mug, jug mug howat hai / koi chunarya orhe sowat hai (The poet’s lady love is sleeping with the chunri all over her torso and the chunri is bright and dazzling). Truly a rough translation! In the movies of the good old days (pardon me for the convenient cliché), the heroine and her best friend often used to exchange their dupattas to establish sisterhood between the two.

The question: why don't they do it now? Simple. Nowadays girls don’t wear dupattas in the movies.

Aanchal is incidentally a favourite subject of Urdu poets, too. An unusual stand was taken by Majaz Lucknavi, when he advised a young woman to make a flag of her dupatta, Tere chehre pe ye aanchal bohat khoob hai lekin; tu is aanchal ko parcham bana deti to achcha tha.

A typical hyperbole, highlighting self-pity, a luxury that our traditional poets indulged in quite often, is reflected in the couplet Na tawan hoon kafan bhi ho halka; Dal do saya apne aanchal ka.

Sahir Ludhianvi, too, indulges in self-pity when he writes "Ashk behte rahein khamosh nigahon se aur tere reshmi anchal ka kinara na mile". The poem was later turned into a film song and velvety-voiced Talat Mahmood, whose voice was as silky as a silk dupatta, imparted poignance to the number from the movie Sone ki chirya. He was accompanied by Asha Bhosle, who hummed beautifully as Talat crooned his heart out. —Asif Noorani