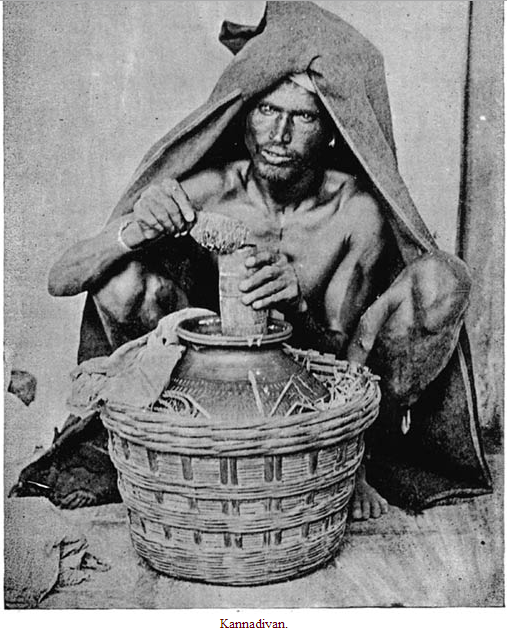

Kannadiyan

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Kannadiyan

The Kannadiyans have been summed up as “immigrants from the province of Mysore. Their traditional occupation is said to have been military service, although they follow, at the present day, different pursuits in different districts. They are usually cattle-breeders and cultivators in North and South Arcot and Chingleput, and traders in the southern districts. Most of them are Lingāyats, but a few are Vaishnavites.” “They are,” it is stated,101 “in the Mysore State known as Gaulis. At their weddings, five married women are selected, who are required to bathe as each of the most important of the marriage ceremonies is performed, and are alone allowed to cook for, or to touch the happy couple. Weddings last eight days, during which time the bride and bridegroom must not sit on anything but woollen blankets.” Some Kannadiyans in the Tanjore district are said to be weavers. For the following account of the Kannadiyans of the Chingleput district I am indebted to Mr. C. Hayavadana Rao.

About twenty miles from the city of Madras is a big tank (lake) named after the village of Chembrambākam, which is close by. The fertile land surrounding this tank is occupied, among others, by a colony of Lingāyats, of whom each household, as a rule, owns several acres of land. With the cultivation thereof, they have the further occupation of cattle grazing. They utilize the products of the cow in various ways, and it supplies them with milk, butter and curds, in the last two of which they carry on a lucrative trade in the city of Madras. The curds sold by them are very highly appreciated by Madras Brāhmans, as they have a sour taste caused by keeping them till fermentation has set in. So great is the demand for their curds that advances of money are made to them, and regular delivery is thus secured. Their price is higher than that of the local Madras curds, and if a Lingāyat buys the latter and sells them at the higher rate, he is decisively stigmatised as being a “local.” They will not even touch sheep and goats, and believe that even the smell of these animals will make cows and buffaloes barren.

Though the chief settlement of the Lingāyats is at Chembrambākam, they are also to be found in the adjacent villages and in the Conjeeveram tāluk, and, in all, they number, in the Chingleput district, about four thousand. The Lingāyats have no idea how their forefathers came to the Chingleput district. Questioned whether they have any relatives in Mysore, many answered in the affirmative, and one even pointed to one in a high official position as a close relation. Another said that the Gurukkal or Jangam (priest) is one and the same man for the Mysore Lingāyats and themselves. A third told me of his grandfather’s wanderings in Mysore, Bellary, and other places of importance to the Lingāyats. I have also heard the story that, on the Chembrambākam Lingāyats being divided into two factions through disputes among the local caste-men, a Lingāyat priest came from Mysore, and brought about their union.

These few facts suffice to show that the Lingāyats are emigrants from Mysore, and not converts from the indigenous populations of the district. But what as to the date of their immigration? The earliest date which can, with any show of reason, be ascribed thereto seems to be towards the end of the seventeenth century, when Chikka Dēva Rāja ruled over Mysore. He adopted violent repressive measures against the Lingāyats for quelling a widespread insurrection, which they had fomented against him throughout the State. His measures of financial reform deprived the Lingāyat priesthood of its local leadership and much of its pecuniary profit. What followed may best be stated in the words of Colonel Wilks, the Mysore historian. “Everywhere the inverted plough, suspended from the tree at the gate of the village, whose shade forms a place of assembly for its inhabitants, announced a state of insurrection. Having determined not to till the land, the husbandmen deserted their villages, and assembled in some places like fugitives seeking a distant settlement; in others as rebels breathing revenge.

Chikka Dēva Rāja, however, was too prompt in his measures to admit of any very formidable combination. Before proceeding to measures of open violence, he adopted a plan of perfidy and horror, yielding to nothing which we find recorded in the annals of the most sanguinary people. An invitation was sent to all the Jangam priests to meet the Rāja at the great temple of Nunjengōd, ostensibly to converse with him on the subject of the refractory conduct of their followers. Treachery was apprehended, and the number which assembled was estimated at about four hundred only. A large pit had been previously prepared in a walled enclosure, connected by a series of squares composed of tent walls with the canopy of audience, at which they were received one at a time, and, after making their obeisance, were desired to retire to a place where, according to custom, they expected to find refreshments prepared at the expense of the Rāja. Expert executioners were in waiting in the square, and every individual in succession was so skilfully beheaded and tumbled into the pit as to give no alarm to those who followed, and the business of the public audience went on without interruption or suspicion. Circular orders had been sent for the destruction on the same day of all the Jangam Mutts (places of residence and worship) in his dominions, and the number reported to have been destroyed was upwards of seven hundred.... This notable achievement was followed by the operations of the troops, chiefly cavalry. The orders were distinct and simple—to charge without parley into the midst of the mob; to cut down every man wearing an orange-coloured robe (the peculiar garb of the Jangam priests).”

How far the husbandmen carried out their threat of seeking a distant settlement it is impossible, at this distance of time, to determine. If the theory of religious persecution as the cause of their emigration has not an air of certainty about it, it is at least plausible.

If the beginning of the eighteenth century is the earliest, the end of that century is the latest date that can be set down for the Lingāyat emigration. That century was perhaps the most troublous one in the modern history of India. Armies were passing and repassing the ghāts, and I have heard from some old gentlemen that the Chingleput Lingāyats, who are mostly shepherds, accompanied the troops in the humble capacity of purveyors of milk and butter. Whatever the causes of their emigration, we find them in the Chingleput district ordinarily reckoning the Mysore, Salem and Bellary Lingāyats as of their own stock. They freely mix with each other, and I hear contract marital alliances with one another. They speak the Kannada (Kanarese) language—the language of Mysore and Bellary. They call themselves by the name of Kannadiyans or Kannadiyars, after the language they speak, and the part of the village they inhabit—Kannadipauliem, or village of the Kannadiyars. In parts of Madras they are known as Kavadi and Kavadiga (=bearers of head-loads).

Both men and women are possessed of great stamina. Almost every other day they walk to and fro, in all seasons, more than twenty miles by road to sell their butter and curds in Madras. While so journeying, they carry on their heads a curd pot in a rattan basket containing three or four Madras measures of curds, besides another pot containing a measure or so of butter. Some of the men are good acrobats and gymnasts, and I have seen a very old man successively break in two four cocoanuts, each placed on three or four crystals of common salt, leaving the crystals almost intact. And I have heard that there are men who can so break fifty cocoanuts—perhaps an exaggeration for a considerable number. In general the women may be termed beautiful, and, in Mysore, the Lingāyat women are, by common consent, regarded as models of feminine beauty.

These Lingāyats are divided into two classes, viz., Gauliyars of Dāmara village, and Kadapēri or Kannadiyars proper, of Chembrambākam and other places. The Gauliyars carry their curd pots in rattan baskets; the Kannadiyars in bamboo baskets. Each class has its own beat in the city of Madras, and, while the majority of the rattan basket men traffic mainly in Triplicane, the bamboo basket men carry on their business in Georgetown and other localities. The two classes worship the same gods, feed together, but do not intermarry. The rattan is considered superior to the bamboo section. Both sections are sub-divided into a large number of exogamous septs or bēdagagulu, of which the meaning, with a few exceptions, e.g., split cane, bear, and fruit of Eugenia Jambolana, is not clear.

Monogamy appears to be the general rule among them, but polygamy to the extent of having two wives, the second to counteract the sterility of the first, is not rare. Marriage before puberty is the rule, which must not be transgressed. And it is a common thing to see small boys grazing the cattle, who are married to babies hardly more than a year old. Marriages are arranged by the parents, or through intermediaries, with the tacit approval of the community as a whole. The marriage ceremony generally lasts about nine or ten days, and, to lessen the expenses for the individual, several families club together and celebrate their marriages simultaneously. All the preliminaries such as inviting the wedding guests, etc., are attended to by the agent of the community, who is called Chaudri. The appointment of agent is hereditary.

The first day of the marriage ceremony is employed in the erection of the booth or pandal. On the following day, the bodice-wearing ceremony is performed. The bride and bridegroom are presented with new clothes, which they put on amid general merriment. In connection with this ceremony, the following Mysore story may not be out of place. When Tipu Sultan once saw a Lingāyat woman selling curds in the street without a body cloth, he ordered the cutting off of her breasts. Since then the wearing of long garments has come into use among the whole female population of Mysore. The third day is the most important, as it is on that day that the Muhūrtham, or tāli-tying ceremony, takes place, and an incident of quite an exceptional character comes off amid general laughter.

A Brāhman (generally a Saivite) is formally invited to attend, and pretends that he is unable to do so. But he is, with mock gravity, pressed hard to do so, and, after repeated guarantees of good faith, he finally consents with great reluctance and misgivings. On his arrival at the marriage booth, the headman of the family in which the marriage is taking place seizes him roughly by the head, and ties as tightly as possible five cocoanuts to the kudumi, or lock of hair at the back of the head, amidst the loud, though not real, protestations of the victim. All those present, with all seriousness, pacify him, and he is cheered by the sight of five rupees, which are presented to him. This gift he readily accepts, together with a pair of new cloths and pān-supāri (betel leaves and areca nuts). Meanwhile the young folk have been making sport of him by throwing at his new and old clothes big empty brinjal fruits (Solanum Melongena) filled with turmeric powder and chunām (lime). He goes for the boys, who dodge him, and at last the elders beat off the youngsters with the remark that “after all he is a Brāhman, and ought not to be trifled with in this way.” The Brāhman then takes leave, and is heard of no more in connection with the wedding rites. The whole ceremony has a decided ring of mockery about it, and leads one to the conclusion that it is celebrated more in derision than in honour of the Brāhmans. It is a notorious fact that the Lingāyats will not even accept water from a Brāhman’s hands, and do not, like many other castes, require his services in connection with marriage or funeral ceremonies.

The practice of tying cocoanuts to the hair of the Brāhman seems to be confined to the bamboo section. But an equally curious custom is observed by the rattan section. The village barber is invited to the wedding, and the infant bride and bridegroom are seated naked before him. He is provided with some ghī(clarified butter) in a cocoanut shell, and has to sprinkle some of it on the head of the couple with a grass or reed. He is, however, prevented from doing so by a somewhat cruel contrivance. A big stone (representing the linga) is suspended from his neck by a rope, and he is kept nodding to and fro by another rope which is pulled by young lads behind him. Eventually they leave off, and he sprinkles the ghī, and is dismissed with a few annas, pān-supāri, and the remains of the ghī. By means of the stone the barber is for the moment turned into a Lingāyat.

The officiating priest at the marriage ceremony is a man of their own sect, and is known as the Gurukkal. They address him as Ayyanavaru, a title generally reserved for Brāhmans in Kannada-speaking districts The main items of expenditure at a wedding are the musician, presents of clothes, and pān-supāri, especially the areca nuts. One man, who was not rich, told me that it cost him, for a marriage, three maunds of nuts, and that guests come more for them than for the meals, which he characterised as not fit for dogs.

Widow remarriage is permitted. But it is essential that the contracting parties should be widower and widow. For such a marriage no pandal is erected, but all the elders countenance it by their presence. Such a marriage is known as naduvīttu tāli, because the tāli is tied in the mid-house. It is usually a simple affair, and finished in a short time after sunset instead of in the day time. The offspring of such marriages are considered as legitimate, and can inherit. But remarried couples are disqualified from performing certain acts, e.g., the distribution of pān-supāri at weddings, partaking in the hārathi ceremony, etc. The disqualifications attaching to remarried people are, by a curious analogy, extended to deformed persons, who are, in some cases, considered to be widowers and widows.

Among the ordinary names of males are Basappa, Linganna, Dēvanna, Ellappa, Naganna; and of females Ellamma, Lingi and Nāgamma. It is said that all are entitled to the honorific Saudri; but the title is specially reserved for the agent of their sect. Among common nicknames are Chikka and Dodda Thamma (younger and elder brother), Āndi (beggar), Karapi (black woman), Gūni (hunch back). In the Mysore Province the most becoming method of addressing a Lingāyat is to call him Sivanē. Their usual titles are Ravut, Appa, Anna, and Saudri.

The child-naming ceremony is a very important one. Five swords with limes fixed to their edges are set in a line with equi-distant spaces between them. By each sword are placed two plantain fruits, a cocoanut, four dried dates, two cocoanut cups, pān-supāri, and kārāmani (Vigna Catiang) cakes. In front of the swords are also placed rice-balls mixed with turmeric powder, various kinds of vegetables and fruits, curds and milk. Opposite each sword five leaves are spread out, and in front of each leaf a near relation of the family sits. The chief woman of the house then brings five pots full of water, and gives to each man a potful for the worship of the jangama linga which he wears. She also brings consecrated cow-dung ashes. The men pour the water over the linga, holding it in the left hand, and smear both the linga and their faces with the ashes. The woman then retires, and the guests partake of a hearty meal, at the conclusion of which the woman reappears with five vessels full of water, with which they wash their hands. The vessels are then broken, and thrown on a dung-heap. After partaking of pān-supāri and chunām (lime), each of the men ties up some of the food in a towel, takes one of the swords in his hand, and leaves the house without turning back. The headman of the family then removes the limes from the swords, and puts them back in their scabbards. The same evening the child is named. Sometimes this ceremony, which is costly, is held even after the child is a year old.

When a death takes place, information is sent round to the relations and castemen by two boys carrying little sticks in their hands. Under the instructions of a priest, the inmates of the house begin to make arrangements for the funeral. The corpse is washed, and the priest’s feet are also washed, and the refuse-water on the ground is poured over the corpse or into its mouth. Among certain sections of Lingāyats it is customary, contrary to the usual Hindu practice, to invite the friends and relations, who have come for the funeral, to a banquet, at which the priest is a guest. It is said that the priest, after partaking of food, vomits a portion of it, which is shared by the members of the family. These practices do not seem to be followed by the Chingleput Lingāyats.

A second bath is given to the corpse, and then the nine orifices of the body are closed with cotton or cloth. The corpse is then dressed as in life, and, if it be that of a priest, is robed in the characteristic orange tawny dress. Before clothing it, the consecrated cow-dung ashes are smeared over the forehead, arms, chest, and abdomen. The bier is made like a car, such as is seen in temple processions on the occasion of car festivals. To each of its four bamboo posts are attached a plantain tree and a cocoanut, and it is decorated with bright flowers. In the middle of the bier is a wooden plank, on which the corpse is set in a sitting position. The priest touches the dead body three or four times with his right leg, and the funeral cortège, accompanied by weird village music, proceeds to the burial-ground.

The corpse, after removal from the bier, is placed in the grave in a sitting posture, facing south, with the linga, which the man had worn during life, in the mouth. Salt, according to the means of the family, is thrown into the grave by friends and relations, and it is considered that a man’s life would be wasted if he did not do this small service for a dead fellow-casteman. They quote the proverb “Did he go unserviceable even for a handful of mud?” The grave is filled in, and four lights are placed at the corners. The priest, standing over the head of the corpse, faces the lamps, with branches of Leucas aspera and Vitex Negundo at his feet.

A cocoanut is broken and camphor burnt, and the priest says “Lingannah (or whatever the name of the dead man may be), leaving Nara Loka, you have gone to Bhu Loka,” which is a little incongruous, for Nara Loka and Bhu Loka are identical. Perhaps the latter is a mistake for Swarga Loka, the abode of bliss of Brāhmanical theology. Possibly, Swarga Loka is not mentioned, because it signifies the abode of Vishnu. Then the priest calls out Oogay! Oogay! and the funeral ceremony is at an end. On their return home the corpse-bearers, priest, and sons of the deceased, take buttermilk, and apply it with the right hand to the left side of the back. A Nandi (the sacred bull) is made of mud, or bricks and mortar, and set up over the grave. Unmarried girls and boys are buried in a lying position. From enquiries made among the Lingāyats of Chembarambākam, it appears that, when a death has occurred, pollution is observed by the near relatives; and, even if they are living at such distant places as Bellary or Bangalore, pollution must be observed, and dissolved by a bath.

Basava attached no importance to pilgrimages. The Chingleput Lingāyats, however, perform what they call Jātray (i.e., pilgrimage), of which the principal celebration takes place in Chittra-Vyasi (April-May), and is called Vīrabhadra Jātray. The bamboo Lingāyats of Chembarambākam send word, with some raw rice, to the rattan Lingāyats of Kadapēri to come to the festival on a fixed day with the image of their god Vīrabhadra. The Gauliyars of Kadapēri and other villages accordingly proceed to a tank on the confines of the village of Chembrambākam, and send word that they have responded to the call of their brethren. The chief men of the village, accompanied by a crowd, and the village musicians, start for the tank, and bring in the Kadapēri guests. After a feast all retire for the night, and get up at 3 A.M. for the celebration of the festival. Swords are unsheathed from their scabbards, and there is a deafening noise from trumpets and pipes. The images of Vīrabhadra are taken in procession to a tank, and, on the way thither, the idol bearers and others pretend that they are inspired, and bawl out the various names of the god. Sometimes they become so frenzied that the people break cocoanuts on their foreheads, or pierce their neck and wrists with a big needle, such as is used in stitching gunny bags. Under this treatment the inspired ones calm down.

All along the route cocoanuts are broken, and may amount to as many as four hundred, which become the perquisite of the village washerman. When the tank is reached, pān-supāri and kadalai (Cicer arietinum) are distributed among the crowd. On the return journey, the village washerman has to spread dupatis (cloths) for the procession to walk over. At about noon a hearty meal is partaken of, and the ceremony is at an end. After a few days, a return celebration takes place at Kadapēri. The Vīrabhadra images of the two sections, it may be noted, are regarded as brothers. Other ceremonial pilgrimages are also made to Tirutāni, Tiruvallūr and Mylapore, and they go to Tiruvallūr on new moon days, bathe in the tank, and make offerings to Vīra Rāghava, a Vaishnava deity. They do not observe the feast of Pongal, which is so widely celebrated throughout Southern India. It is said that the celebration thereof was stopped, because, on one occasion, the cattle bolted, and the men who went in pursuit of them never returned. The Ugādi, or new year feast, is observed by them as a day of general mourning. They also observe the Kāma festival with great éclat, and one of their national songs relates to the burning of Kāma. When singing it during their journeys with the curd-pots, they are said to lose themselves, and arrive at their destination without knowing the distance that they have marched.

In addition to the grand Vīrabhadra festival, which is celebrated annually, the Arisērvai festival is also observed as a great occasion. This is no doubt a Tamil rendering of the Sanskrit Harisērvai, which means the service of Hari or worship of Vishnu. It is strange that Lingāyats should have this formal worship of Vishnu, and it must be a result of their environment, as they are surrounded on all sides by Vaishnavite temples. More than six months before the festival a meeting of elders is convened, and it is decided that an assessment of three pies per basket shall be levied, and the Saudri is made honorary treasurer of the fund. If a house has two or more baskets, i.e., persons using baskets in their trade, it must contribute a corresponding number of three pies. In other words, the basket, and not the family, is the unit in their communal finance.

An invitation, accompanied by pān-supāri, is sent to the Thādans (Vaishnavite dramatists) near Conjeeveram, asking them to attend the festival on the last Saturday of Paratāsi, the four Saturdays of which month are consecrated to Vishnu. The Thādans arrive in due course at Chembrambākam, the centre of the bamboo section of the Lingāyats, and make arrangements for the festival. Invitations are sent to five persons of the Lingāyat community, who fast from morning till evening. About 8 or 9 P.M., these five guests, who perhaps represent priests for the occasion, arrive at the pandal (booth), and leaves are spread out before them, and a meal of rice, dhal (Cajanus indicus) water, cakes, broken cocoanuts, etc., is served to them. But, instead of partaking thereof, they sit looking towards a lighted lamp, and close their eyes in meditation. They then quietly retire to their homes, where they take the evening meal. After a torchlight procession with torches fed with ghī (clarified butter) the village washermen come to the pandal, and collect together the leaves and food, which have been left there. About 11 P.M. the villagers repair to the spot where a dramatic performance of Hiranya Kasyapa Nātakam, or the Prahallāda Charitram, is held during five alternate nights. The latter play is based on a favourite story in the Bhāgavatha, and it is strange that it should be got up and witnessed by a community of Saivites, some of whom (Vīra Saivas) are such extremists that they would not tolerate the sight of a Vaishnavite at a distance.

The Chembrambākam Lingāyats appear to join the other villagers in the performance of the annual pūja (worship) to the village deity, Nāmamdamma, who is worshipped in order to ward off cholera and cattle disease. One mode of propitiating her is by sacrificing a goat, collecting its entrails and placing them in a pot, with its mouth covered with goat skin, which is taken round the village, and buried in a corner. The pot is called Bali Sētti, and he who comes in front of it while it is being carried through the streets, is supposed to be sure to suffer from serious illness, or even die. The sacrifice, filling of the pot, and its carriage through the streets, are all performed by low class Ōcchans and Vettiyāns. The Chembrambākam Lingāyats assert that the cholera goddess has given a promise that she will not attack any of their community, and keeps it faithfully, and none of them die even during the worst cholera epidemics.