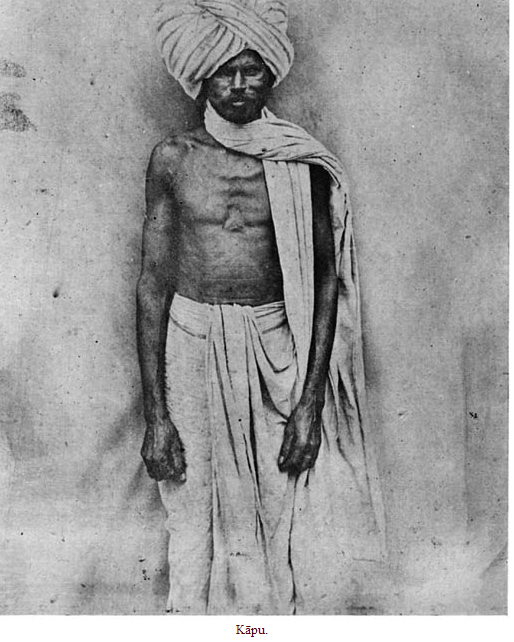

Kāpu

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Kāpu

The Kāpus or Reddis are the largest caste in the Madras Presidency, numbering more than two millions, and are the great caste of cultivators, farmers, and squireens in the Telugu country. In the Gazetteer of Anantapur they are described as being the great land-holding body in the Telugu districts, who are held in much respect as substantial, steady-going yeomen, and next to the Brāhmans are the leaders of Hindu Society. In the Salem Manual it is stated that “the Reddis are provident. They spend their money on the land, but are not parsimonious. They are always well dressed, if they can afford it. The gold ornaments worn by the women or the men are of the finest kind of gold. Their houses are always neat and well built, and the Reddis give the idea of good substantial ryots. They live chiefly on rāgi (grain: Eleusine Coracana), and are a fine, powerful race.” Of proverbs relating to the hereditary occupation of the Reddis, the following may be quoted. “Only a Reddi can cultivate the land, even though he has to drink for every clod turned over.” “Those are Reddis who get their living by cultivating the earth.” “The Reddi who grows arika (Paspalum strobiculatum) can have but one cloth for man and wife.”

“The term Kāpu,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, “means a watchman, and Reddi means a king. The Kāpus or Reddis (Ratti) appear to have been a powerful Dravidian tribe in the early centuries of the Christian era, for they have left traces of their presence at various places in almost every part of India. Though their power has been put down from time to time by the Chālukyas, the Pallavas, and the Bellālas, several families of zamindars came into existence after the captivity of Pratāpa Rudra of Warrangal in A.D. 1323 by the Muhammadan emperor Ghiyas-ud-dīn Toghluk.”

Writing in the Manual of the Salem district concerning the Kongu kingdom, the Rev. T. Foulkes states that “the Kongu kingdom claims to have existed from about the commencement of the Christian era, and to have continued under its own independent kings down to nearly the end of the ninth century A.D., when it was conquered by the Chola kings of Tanjore, and annexed to their dominions. The earliest portion of the Kongu Chronicle (one of the manuscripts of the Mackenzie collection) gives a series of short notices of the reigns of twenty-eight kings who ruled the country previous to its conquest by the Cholas. These kings belonged to two distinct dynasties: the earlier line was of the solar race, and the later line of the Ganga race.

The earlier dynasty had a succession of seven kings of the Ratti tribe, a tribe very extensively distributed, which has at various periods left its mark throughout almost every part of India. This is probably the earliest reference to them as a ruling power, and it is the most southern situation in which they ever held dominion. They disappear in these parts about the end of the second century A.D.; and, in the next historical references to them, we find them high up in the Northern Dakkan, amongst the kingdoms conquered by the Chālukyas about the fourth century A.D. soon after they first crossed the Nerbudda. In the Kongu Chronicle they are stated to be of the solar race: and the genealogies of this tribe accordingly trace them up to Kusha, the second son of Rāma, the hero of the great solar epic of the Hindus; but their claim to this descent is not undisputed. They are, however, sometimes said to be of the lunar race, and of the Yādava tribe, though this latter statement is sometimes confined to the later Rāthors.” According to the Rev. T. Foulkes, the name Ratti is found under various forms, e.g., Irattu, Iretti, Radda, Rāhtor, Rathaur, Rāshtra-kūta, Ratta, Reddi, etc.

In a note on the Rāshtrakutas, Mr. J. F. Fleet writes that “we find that, from the first appearance of the Chalukyas in this part of the country, in the fifth century A.D., the Kanarese districts of the Bombay Presidency were held by them, with short periods of interruption of their power caused by the invasions of the Pallavas and other kings, down to about the early part or the middle of the eighth century A.D. Their sway over this part of the country then ceased entirely for a time. This was due to an invasion by the Rāshtrakuta kings, who, like their predecessors, came from the north.... It is difficult to say when there was first a Rāshtrakuta kingdom. The earliest notices that we have of the family are contained in the western Chalukya inscriptions. Thus, the Miraj plates tell us that Jayasimha I, restored the fortunes of the Chalukya dynasty by defeating, among others, one Indra of the Rāshtrakuta family, who was the son of Krishna, and who possessed an army of eight hundred elephants; and there is little doubt that Āppāyika-Govinda, who, as we are told in the Aihole Meguti inscription, came from the north and invaded the Chalukya kingdom with his troops of elephants, and was repulsed by Pulikesi II, also belonged to this same dynasty.

It is plain, therefore, that in the fifth and sixth centuries A.D. the Rāshtrakuta dynasty was one of considerable importance in central or in northern India. The later inscriptions state that the Rāshtrakutas were of the Somavamsa or lunar race, and were descendants of Yadu. Dr. Burnell seems inclined to look upon the family as of Dravidian origin, as he gives ‘Rāshtra’ as an instance of the Sanskritising of Dravidian names, and considers it to be a mythological perversion for ‘Ratta,’ which is the same as the Kanarese and Telugu ‘Reddi.’ Dr. Bühler is unable to record any opinion as to ‘whether the Rāshtrakutas were an Āryan Kshatriya, i.e., Rājput race, which immigrated into the Dekkan from the north like the Chalukyas, or a Drāvidian family which was received into the Āryan community after the conquest of the Dekkan.’ The earliest inscriptions, at any rate, show them as coming from the north, and, whatever may be their origin, as the word Rāshtrakuta is used in many inscriptions of other dynasties as the equivalent of Rāshtrapati, i.e., as an official word meaning ‘the headman or governor of a country or district,’ it appears to me that the selection of it as a dynastic name implies that, prior to attaining independent sovereignty, the Rāshtrakutas were feudal chiefs under some previous dynasty, of which they have not preserved any record.”

It is a common saying among the Kāpus that they can easily enumerate all the varieties of rice, but it is impossible to give the names of all the sections into which the caste is split up. Some say that there are only fourteen of these, and use the phrase Panta padnālagu kulālu, or Panta and fourteen sections.

The following sub-divisions are recorded by Mr. Stuart as being the most important:—

Ayōdhya, or Oudh, where Rāma is reputed to have lived. The sub-division is found in Madura and Tinnevelly. They are very proud of their supposed connection with Oudh. At the commencement of the marriage ceremony, the bride’s party asks the bridegroom’s who they are, and the answer is that they are Ayōdhya Reddis. A similar question is then asked by the bridegroom’s party, and the bride’s friends reply that they are Mithila Reddis. Balija. The chief Telugu trading caste. Many of the Balijas are now engaged in cultivation, and this accounts for so many having returned Kāpu as their main caste, for Kāpu is a common Telugu word for a ryot or cultivator. It is not improbable that there was once a closer connection than now between the Kāpus and Balijas. Bhūmanchi (good earth).

Dēsūr. Possibly residents originally of a place called Dēsūr, though some derive the word from dēha, body, and sūra, valour, saying that they were renowned for their courage.

Gandi Kottai. Found in Madura and Tinnevelly. Named after Gandi Kōta in the Ceded districts, whence they are said to have emigrated southward.

Gāzula (glass bangle makers). A sub-division of the Balijas. They are said to have two sections, called Nāga (cobra) and Tābēlu (tortoise), and, in some places, to keep their women gōsha.

Kammapuri. These seem to be Kammas, who, in some places, pass as Kāpus. Some Kammas, for example, who have settled in the city of Madras, call themselves Kāpu or Reddi.

Morasa. A sub-division of the Vakkaligas. The Verala icche Kāpulu, or Kāpus who give the fingers, have a custom which requires that, when a grandchild is born in a family, the wife of the eldest son of the grandfather must have the last two joints of the third and fourth fingers of her right hand amputated at a temple of Bhairava.

Nerati, Nervati, or Neradu. Most numerous in Kurnool, and the Ceded districts.

Oraganti. Said to have formerly worked in the salt-pans. The name is possibly a corruption of Warangal, capital of the Pratāpa Rudra.

Pākanāti. Those who come from the eastern country (prāk nādu).

Palle. In some places, the Pallis who have settled in the Telugu country call themselves Palle Kāpulu, and give as their gōtra Jambumāha Rishi, which is the gōtra of the Pallis. Though they do not intermarry with the Kāpus, the Palle Kāpulu may interdine with them.

Panta (Panta, a crop). The largest sub-division of all.

Pedaganti or Pedakanti. By some said to be named after a place called Pedagallu. By others the word is said to be derived from peda, turned aside, and kamma eye, indicating one who turns his eyes away from the person who speaks to him. Another suggestion is that it means stiff-necked. The Pedakantis are said to be known by their arrogance.

The following legend is narrated in the Baramahal Records. “On a time, the Guru or Patriarch came near a village, and put up in a neighbouring grove until he sent in a Dāsari to apprize his sectaries of his approach. The Dāsari called at the house of one of them, and announced the arrival of the Guru, but the master of the house took no notice of him, and, to avoid the Guru, he ran away through the back door of the house, which is called peradu, and by chance came to the grove, and was obliged to pay his respects to the Guru, who asked if he had seen his Dāsari, and he answered that he had been all day from home. On which, the Guru sent for the Dāsari, and demanded the reason of his staying away so long, when he saw the master of the house was not in it. The Dāsari replied that the person was at home when he went there, but that, on seeing him, he fled through the back door, which the Guru finding true, he surnamed him the Peratiguntavaru or the runaway through the back door, now corruptly called Perdagantuwaru, and said that he would never honour him with another visit, and that he and his descendants should henceforth have no Guru or Patriarch.” Pōkanādu (pōka, areca palm: Areca Catechu).

Velanāti. Kāpus from a foreign (veli) country.

Yerlam.

“The last division,” Mr. Stuart writes, “are the most peculiar of all, and are partly of Brāhmanical descent. The story goes that a Brāhman girl named Yerlamma, not having been married by her parents in childhood, as she should have been, was for that reason turned out of her caste. A Kāpu, or some say a Besta man, took compassion on her, and to him she bore many children, the ancestors of the Yerlam Kāpu caste. In consequence of the harsh treatment of Yerlamma by her parents and caste people, all her descendants hate Brāhmans with a deadly hatred, and look down upon them, affecting also to be superior to every other caste. They are most exclusive, refusing to eat with any caste whatever, or even to take chunam (lime for chewing with betel) from any but their own people, whereas Brāhmans will take lime from a Sūdra, provided a little curd be mixed with it. The Yerlam Kāpus do not employ priests of the Brāhman or other religious classes even for their marriages. At these no hōmam (sacred fire) ceremony is performed, and no worship offered to Vignēswara, but they simply ascertain a fortunate day and hour, and get an old matron (sumangali) to tie the tāli to the bride’s neck, after which there is feasting and merry-making.”

The Panta Kāpus are said to be divided into two tegas or endogamous divisions, viz., Peramā Reddi or Muduru Kāpu (ripe or old Kāpu); and Kātama Reddi or Letha Kāpu (young or unripe Kāpus). A sub-division called Konda (hill) Kāpus is mentioned by the Rev. J. Cain as being engaged in cultivation and the timber trade in the eastern ghāts near the Godāvari river (see Konda Dora). Ākula (betel-leaf seller) was returned at the census, 1901, as a sub-caste of Kāpus. In the Census Report, 1891, Kāpu (indicating cultivator), is given as a sub-division of Chakkiliyans, Dommaras, Gadabas, Savaras and Tēlis. It further occurs as a sub-division of Mangala. Some Marātha cultivators in the Telugu country are known as Arē Kāpu. The Konda Doras are also called Konda Kāpus. In the Census Report, 1901, Pandu is returned as a Tamil synonym, and Kāmpo as an Oriya form of Kāpu.

Reddi is the usual title of the Kāpus, and is the title by which the village munsiff is called in the Telugu country, regardless of the caste to which he may belong. Reddi also occurs as a sub-division of cultivating Linga Balijas, Telugu Vadukans or Vadugans in the Tamil country, Velamas, and Yānādis. It is further given as a name for Kavarais engaged in agriculture, and as a title of the Kallangi sub-division of Pallis, and Sādars. The name Sambuni Reddi is adopted by some Palles engaged as fishermen.

As examples of exogamous septs among the Kāpus, the following may be cited:— • Avula, cow.

• Alla, grain.

• Bandi, cart.

• Barrelu, buffaloes.

• Dandu, army.

• Gorre, sheep.

• Gudise, hut.

• Guntaka, harrow.

• Kōdla, fowl.

• Mēkala, goats.

• Kānugala, Pongamia glabra.

• Mungāru, woman’s skirt.

• Nāgali, plough.

• Tangēdu, Cassia auriculata.

• Udumala, Varanus bengalensis.

• Varige, Setaria italica.

• Yeddulu, bulls.

• Yēnuga, elephant.

At Conjeeveram, some Panta Reddis have true totemistic septs, of which the following are examples:— Magili (Pandanus fascicularis). Women do not, like women of other castes, use the flower-bracts for the purpose of adorning themselves. A man has been known to refuse to purchase some bamboo mats, because they were tied with the fibre of this tree.

Ippi (Bassia longifolia). The tree, and its products, must not be touched.

Mancham (cot). They avoid sleeping on cots.

Arigala (Paspalum scrobiculatum). The grain is not used as food.

Chintaginjalu (tamarind seeds). The seeds may not be touched, or used.

Puccha (Citrullus vulgaris; water melon). The fruit may not be eaten.

The Pichigunta vandlu, a class of mendicants who beg chiefly from Kāpus and Gollas, manufacture pedigrees and gōtras for these castes and the Kammas.

Concerning the origin of the Kāpus, the following legend is current. During the reign of Pratāpa Rudra, the wife of one Belthi Reddi secured by severe penance a brilliant ear ornament (kamma) from the sun. This was stolen by the King’s minister, as the King was very anxious to secure it for his wife. Belthi Reddi’s wife told her sons to recover it, but her eldest son refused to have anything to do with the matter, as the King was involved in it. The second son likewise refused, and used foul language. The third son promised to secure it, and, hearing this, one of his brothers ran away. Finally the ornament was recovered by the youngest son. The Panta Kāpus are said to be descended from the eldest son, the Pākanātis from the second, the Velamas from the son who ran away, and the Kammas from the son who secured the jewel.

The Kāpus are said to have originally dwelt in Ayōdhya. During the reign of Bharata, one Pillala Mari Belthi Reddi and his sons deceived the King by appropriating all the grain to themselves, and giving him the straw. The fraud was detected by Rāma when he assumed charge of the kingdom, and, as a punishment, he ordered the Kāpus to bring Cucurbita (pumpkin) fruits for the srādh (death ceremony) of Dasarātha. They accordingly cultivated the plant, but, before the ceremony took place, all the plants were uprooted by Hanumān, and no fruits were forthcoming. In lieu thereof, they promised to offer gold equal in weight to that of the pumpkin, and brought all of which they were possessed. This they placed in the scales, but it was not sufficient to counterbalance a pumpkin against which it was weighed. To make up the deficiency in weight, the Kāpu women removed their bottus (marriage badges), and placed them in the scales.

Since that time women of the Mōtāti and Pedakanti sections have substituted a cotton string dyed with turmeric for the bottu. It is worthy of notice that a similar legend is current among the Vakkaligas (cultivators) of Mysore, who, instead of giving up the bottu, seem to have abandoned the cultivation of the Cucurbita plant. The exposure of the fraud led Belthi Reddi to leave Ayōdhya with one of his wives and seventy-seven children, leaving behind thirteen wives. In the course of their journey, they had [233]to cross the Silānadi (petrifying river), and, if they passed through the water, they would have become petrified. So they went to a place called Dhonakonda, and, after worshipping Ganga, the head of the idol was cut off, and brought to the river bank. The waters, like those of the Red Sea in the time of Pharaoh, were divided, and the Kāpus crossed on dry ground. In commemoration of this event, the Kāpus still worship Ganga during their marriage ceremonies. After crossing the river, the travellers came to the temple of Mallikarjuna, and helped the Jangams in the duties of looking after it.

Some time afterwards the Jangams left the place for a time, and placed the temple in charge of the Kāpus. On their return, the Kāpus refused to hand over charge to them, and it was decided that whoever should go to Nāgalōkam (the abode of snakes), and bring back Nāga Malligai (jasmine from snake-land), should be considered the rightful owner of the temple. The Jangams, who were skilled in the art of transformation, leaving their mortal frames, went in search of the flower in the guise of spirits. Taking advantage of this, the Kāpus burnt the bodies of the Jangams, and, when the spirits returned, there were no bodies for them to enter. Thereon the god of the temple became angry, and transformed the Jangams into crows, which attacked the Kāpus, who fled to the country of Oraganti Pratāpa Rudra.

As this King was a Sakti worshipper, the crows ceased to harass the Kāpus, who settled down as cultivators. Of the produce of the land, nine-tenths were to be given to the King, and the Kāpus were to keep a tithe. At this time the wife of Belthi Reddi was pregnant, and she asked her sons what they would give to the son who was about to be born. They all promised to give him half their earnings. The child grew into a learned man and poet, and one day carried water to the field where his brothers were at work. The vessel containing the water was only a small one, and there was not enough water for all. But he prayed to Sarasvati, with whose aid the vessel was always filled up. Towards evening, the grain collected during the day was heaped together, with a view to setting apart the share for the King. But a dispute arose among the brothers, and it was decided that only a tithe should be given to him. The King, being annoyed with the Kāpus for not giving him his proper share, waited for an opportunity to bring disgrace on Belthi Reddi, and sought the assistance of a Jangam, who managed to become the servant of Belthi Reddi’s wife. After some time, he picked up her kamma when it fell off while she was asleep, and handed it over to Pratāpa Rudra, who caused it to be proclaimed that he had secured the ornament as a preliminary to securing the person of its owner. The eldest son of Belthi Reddi, however, recovered the kamma in a fight with the King, during which he carried his youngest brother on his back. From him the Kammas are descended. The Velamas are descended from the sons who ran away, and the Kāpus from those who would neither fight nor run away.

Pollution at the first menstrual ceremony lasts, I am informed, for sixteen days. Every day, both morning and evening, a dose of gingelly (Sesamum) oil is administered to the girl, and, if it produces much purging, she is treated with buffalo ghī (clarified butter). On alternate days water is poured over her head, and from the neck downwards. The cloth which she wears, whether new or old, becomes the property of the washerwoman. On the first day the meals consist of milk and dhāl (Cajanus indicus), but on subsequent days cakes, etc., are allowed.

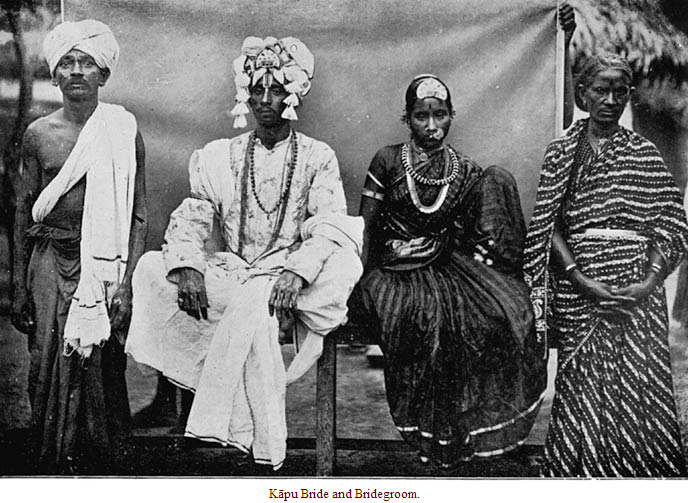

In their marriage ceremonial, the Panta Reddis of the South Arcot and Salem districts appear to follow the Brāhmanical form. In the Telugu country, however, it is as follows. On the pradhānam or betrothal day, the party of the bridegroom-elect go in procession under a canopy (ulladam), attended by musicians, and matrons carrying betel, cocoanuts, date and plantain fruits, and turmeric on plates. As soon as they have arrived at the courtyard of the future bride’s house, she seats herself on a plank. A Brāhman purōhit moulds a little turmeric paste into a conical mass representing Vignēswara (the elephant god), and it is worshipped by the girl, in front of whom the trays brought by the women are placed. She is presented with a new cloth, which she puts on, and a near female relation gives her three handfuls of areca nuts, a few betel leaves, and the bride-price and jewels tied up in a turmeric-dyed cloth.

All these things the girl deposits in her lap. The fathers of the contracting couple then exchange betel, with the customary formula. “The girl is yours, and the money mine” and “The money is yours, and the girl mine.” Early on the wedding morning the bridegroom’s party, accompanied by a purōhit and washerman (Tsākala), go to fetch the bride from her house. The milk-post is set up, and is usually made of a branch of Mimusops hexandra or, in the Tamil country, Odina Wodier. On the conclusion of the marriage rites, the Odina post is planted in the backyard, and, if it takes root and flourishes, it is regarded as a happy omen for the newly married couple. A small party of Kāpus, taking with them some food and gingelly (Sesamum) oil, proceed in procession beneath a canopy to the house of a washerman (Tsākala), in order to obtain from him a framework made of bamboo or sticks over which cotton threads are wound (dhornam), and the Ganga idol, which is kept in his custody. The food is presented to him, and some rice poured into his cloth. Receiving these things, he says that he cannot find the dhornam and idol without a torch-light, and demands gingelly oil.

This is given to him, and the Kāpus return with the washerman carrying the dhornam and idol to the marriage house. When they arrive at the entrance thereto, red coloured food, coloured water (ārathi) and incense are waved before the idol, which is taken into a room, and placed on a settle of rice. The washerman is then asked to tie the dhornam to the pandal (marriage booth) or roof of the house, and he demands some paddy, which is heaped up on the ground. Standing thereon, he ties the dhornam. The people next proceed to the houses of the goldsmith and potter, and bring back the bottu (marriage badge) and thirteen marriage pots, on which threads (kankanam) are tied before they are removed. A Brāhman purōhit ties the thread round one pot, and the Kāpus round the rest. The pots are placed in the room along with the Ganga idol. The bottu is tied round the neck of a married woman who is closely related to the bridegroom.

The contracting couple are seated with the ends of their clothes tied together. A barber comes with a cup of water, and a tray containing rice dyed with turmeric is placed on the floor. A number of men and women then scatter rice over the heads of the bride and bridegroom, and, after, waving a silver or copper coin in front of them, throw it into the barber’s cup. The barber then pares the finger and toe nails of the bridegroom, and touches the toe nails of the bride with his razor. They then go through the nalagu ceremony, being smeared with oil and Phaseolus Mungo paste, and bathe. After the bath the bridegroom, dressed in his wedding finery, proceeds to the temple. As he leaves the house, a Mādiga hands him a pair of shoes, which he puts on. The Mādiga is given food placed in a basket on eleven leaves. At the temple worship is performed, and a Bhatrāzu (bard and panegyrist), who has accompanied the bridegroom, ties a bāshingham (chaplet) on his forehead. From this moment the Bhatrāzu must remain with the bridegroom, as his personal attendant, painting the sectarian marks on his forehead, and carrying out other functions. In like manner, a Bhōgam woman (dedicated prostitute) waits on the bride. “The tradition,” Mr. Stuart writes, “is that the Bhatrāzus were a northern caste, which was first invited south by king Pratāpa Rudra of the Kshatriya dynasty of Warrangal (1295–1323 A.D.).

After the downfall of that kingdom they seem to have become court bards and panegyrists under the Reddi and Velama feudal chiefs.” From the temple the bridegroom and his party come to the marriage pandal, and, after food and other things have been waved to avert the evil eye, he enters the house. On the threshold his brother-in-law washes his feet, and sits thereon till he has extracted some money or a cow as a present. The bridegroom then goes to the marriage dais, whither the bride is conducted, and stands facing him, with a screen interposed between them. Vignēswara is worshipped, and the wrist threads (kankanam) are tied on, the bridegroom placing his right foot on the left foot of the bride. The bottu is removed from the neck of the married woman, passed round to be blessed, and tied by the bridegroom on the bride’s neck. The bride is lifted up by her maternal uncle, and the couple sprinkle each other with rice.

The screen is removed, and they sit side by side with the ends of their cloths tied together. Rice is thrown over them by those assembled, and they are made to gaze at the pole star (Arundati). The proceedings terminate by the pair searching for a finger-ring and pap-bowl in one of the pots filled with water. On the second day there is feasting, and the nalagu ceremony is again performed. On the following day, the bridegroom and his party pretend to take offence at some thing which is done by the bride’s people, who follow them with presents, and a reconciliation is speedily effected. Towards evening, a ceremony called nāgavali, or sacrifice to the Dēvatas, is performed. The bridal pair, with the Bhatrāzu and Bhōgam woman, occupy the dais. The Brāhman purōhit places on a tray a conical mass of turmeric representing Vignēswara, to whom pūja (worship) is done. He then places a brass vessel (kalasam) filled with water, and with its mouth closed by a cocoanut, on a settle of rice spread on a tray. The kalasam is worshipped as representing the Dēvatas. The Brāhman invokes the blessing of all the Gods and Dēvatas, saying “Let Siva bless the pair,” “Let Indra bless the pair,” etc. A near relative of the bridegroom sits by the side of the purōhit with plenty of betel leaves and areca nuts. After each God or Dēvata has been mentioned, he throws some of the nuts and leaves into a tray, and, as these are the perquisites of the purōhit, he may repeat the same name three or four times. The Kāpu then makes playful remarks about the greed of the purōhit, and, amid much laughter, refuses to put any more leaves or nuts in the tray.

This ceremonial concluded, the near relations of the bridegroom stand in front of him, and, with hands crossed, hold over his head two brass plates, into which a small quantity of milk is poured. Fruit, betel leaves and areca nuts (pān-supāri) are next distributed in a recognised order of precedence. The first presentation is made to the house god, the second to the family priest, and the third to the Brāhman purōhit. If a Pākanāti Kāpu is present, he must receive his share immediately after the Brāhman, and before other Kāpus, Kammas, and others. Before it is presented to each person, the leaves and nuts are touched by the bridegroom, and the hand of the bride is placed on them by the Bhōgam woman.

At a Panta Kāpu wedding, the Ganga idol, together with a goat and a kāvadi (bamboo pole with baskets of rice, cakes, betel leaves and areca nuts), is carried in procession to a pond or temple. The washerman, dressed up as a woman, heads the procession, and keeps on dancing and singing till the destination is reached. The idol is placed inside a rude triangular hut made of three sheaves of straw, and the articles brought in the baskets are spread before it. On the heap of rice small lumps of flour paste are placed, and these are made into lights by scooping out cavities, and feeding the wicks with ghī (clarified butter). One of the ears of the goat is then cut, and it is brought near the food. This done, the lights are extinguished, and the assembly returns home without the least noise. The washerman takes charge of the idol, and goes his way. If the wedding is spread over five days, the Ganga idol is removed on the fourth day, and the customary mock-ploughing ceremony performed on the fifth. The marriage ceremonies close with the removal of the threads from the wrists of the newly married couple. Among the Panta Reddis of the Tamil country, the Ganga idol is taken in procession by the washerman two or three days before the marriage, and he goes to every Reddi house, and receives a present of money. The idol is then set up in the verandah, and worshipped daily till the conclusion of the marriage ceremonies.

“Among the Reddis of Tinnevelly,” Dr. J. Shortt writes, “a young woman of sixteen or twenty years of age is frequently married to a boy of five or six years, or even of a more tender age. After marriage she, the wife, lives with some other man, a near relative on the maternal side, frequently an uncle, and sometimes with the boy-husband’s own father. The progeny so begotten are affiliated on the boy-husband. When he comes of age, he finds his wife an old woman, and perhaps past child-bearing. So he, in his turn, contracts a liaison with some other boy’s wife, and procreates children.” The custom has doubtless been adopted in imitation of the Maravans, Kallans, Agamudaiyans, and other castes, among whom the Reddis have settled. In an account of the Ayōdhya Reddis of Tinnevelly, Mr. Stuart writes that it is stated that “the tāli is peculiar, consisting of a number of cotton threads besmeared with turmeric, without any gold ornament. They have a proverb that he who went forth to procure a tāli and a cloth never returned.” This proverb is based on the following legend. In days of yore a Reddi chief was about to be married, and he accordingly sent for a goldsmith, and, desiring him to make a splendid tāli, gave him the price of it in advance. The smith was a drunkard, and neglected his work. The day for the celebration of the marriage arrived, but there was no tāli. Whereupon the old chief, plucking a few threads from his garment, twisted them into a cord, and tied it round the neck of the bride, and this became a custom.

In the Census Report, 1891, Mr. Stuart states that he was informed that polyandry of the fraternal type exists among the Panta Kāpus, but the statement requires verification. I am unable to discover any trace of this custom, and it appears that Reddi Yānādis are employed by Panta Reddis as domestic servants. If a Reddi Yānādi’s husband dies, abandons, or divorces his wife, she may marry his brother. And, in the case of separation or divorce, the two brothers will live on friendly terms with each other.

In the Indian Law Reports it is noted that the custom of illatom, or affiliation of a son-in-law, obtains among the Mōtāti Kāpus in Bellary and Kurnool, and the Pedda Kāpus in Nellore. He who has at the time no son, although he may have more than one daughter, and whether or not he is hopeless of having male issue, may exercise the right of taking an illatom son-in-law. For the purposes of succession this son-in-law stands in the place of a son, and, in competition with natural-born sons, takes an equal share.

According to the Kurnool Manual (1886), “the Pakanādus of Pattikonda and Rāmallakōta tāluks allow a widow to take a second husband from among the caste-men. She can wear no signs of marriage, such as the tāli, glass bangles, and the like, but she as well as her husband is allowed to associate with the other caste-men on equal terms. Their progeny inherit their father’s property equally with children born in regular wedlock, but they generally intermarry with persons similarly circumstanced. Their marriage with the issue of a regularly married couple is, however, not prohibited. It is matter for regret that this privilege of remarrying is much abused, as among the Linga Balijas. Not unfrequently it extends to pregnant widows also, and so widows live in adultery with a caste-man without fear of excommunication, encouraged by the hope of getting herself united to him or some other caste-man in the event of pregnancy. In many cases, caste-men are hired for the purpose of going through the forms of marriage simply to relieve such widows from the penalty of excommunication from caste. The man so hired plays the part of husband for a few days, and then goes away in accordance with his secret contract.” The abuse of widow marriage here referred to is said to be uncommon, though it is sometimes practiced among Kāpus and other castes in out-of-the-way villages. It is further noted in the Kurnool Manual that Pedakanti Kāpu women do not wear the tāli, or a bodice (ravika) to cover their breasts. And the tight-fitting bodice is said to be “far less universal in Anantapur than Bellary, and, among some castes (e.g., certain sub-divisions of the Kāpus and Īdigas), it is not worn after the first confinement.”

In the disposal of their dead, the rites among the Kāpus of the Telugu country are very similar to those of the Kammas and Balijas. The Panta Reddis of the Tamil country, however, follow the ceremonial in vogue among various Tamil castes. The news of a death in the community is conveyed by a Paraiyan Tōti (sweeper). The dead man’s son receives a measure containing a light from a barber, and goes three times round the corpse. At the burning-ground the barber, instead of the son, goes thrice round the corpse, carrying a pot containing water, and followed by the son, who makes holes therein. The stream of water which trickles out is sprinkled over the corpse. The barber then breaks the pot into very small fragments. If the fragments were large, water might collect in them, and be drunk by birds, which would bring sickness (pakshidhōsham) on children, over whose heads they might pass. On the day after the funeral, a Panisavan or barber extinguishes the fire, and collects the ashes together. A washerman brings a basket containing various articles required for worship, and, after pūja has been performed, a plant of Leucas aspera is placed on the ashes. The bones are collected in a new pot, and thrown into a river, or consigned by parcel-post to an agent at Benares, and thrown into the Ganges.

By religion the Kāpus are both Vaishnavites and Saivites, and they worship a variety of deities, such as Thāllamma, Nāgarapamma, Putlamma, Ankamma, Munēswara, Pōleramma, Dēsamma. To Munēswara and Dēsamma pongal (cooked rice) is offered, and buffaloes are sacrificed to Pōleramma. Even Mātangi, the goddess of the Mādigas, is worshipped by some Kāpus. At purificatory ceremonies a Mādiga Basavi woman, called Mātangi, is sent for, and cleanses the house or its inmates from pollution by sprinkling and spitting out toddy.

From an interesting note on agricultural ceremonies in the Bellary district, the following extract is taken. “On the first full-moon day in the month of Bhādrapada (September), the agricultural population celebrate a feast called the Jokumāra feast, to appease the rain-god. The Bārikas (women), who are a sub-division of the Kabbēra caste belonging to the Gaurimakkalu section, go round the town or village in which they live, with a basket on their heads containing margosa (Melia Azadirachta) leaves, flowers of various kinds, and holy ashes. They beg alms, especially of the cultivating classes (Kāpus), and, in return for the alms bestowed (usually grain and food), they give some of the margosa leaves, flowers, and ashes. The Kāpus take these to their fields, prepare cholam (millet: Sorghum) gruel, mix them with it, and sprinkle the kanji or gruel all round their fields.

After this, the Kāpu proceeds to the potter’s kiln, fetches ashes from it, and makes a figure of a human being. This figure is placed prominently in some convenient spot in the field, and is called Jokumāra or rain-god. It is supposed to have the power of bringing down the rain in proper time. The figure is sometimes small, and sometimes big. A second kind of Jokumāra worship is called muddam, or outlining of rude representations of human figures with powdered charcoal. These representations are made in the early morning, before the bustle of the day commences, on the ground at crossroads and along thoroughfares. The Bārikas who draw these figures are paid a small remuneration in money or in kind. The figure represents Jokumāra, who will bring down rain when insulted by people treading on him. Another kind of Jokumāra worship also prevails in this district. When rain fails, the Kāpu females model a figure of a naked human being of small size. They place this figure in an open mock palanquin, and go from door to door singing indecent songs, and collecting alms. They continue this procession for three or four days, and then abandon the figure in a field adjacent to the village.

The Mālas then take possession of this abandoned Jokumāra, and in their turn go about singing indecent songs and collecting alms for three or four days, and then throw it away in some jungle. This form of Jokumāra worship is also believed to bring down plenty of rain. There is another simple superstition among these Kāpu females. When rain fails, the Kāpu females catch hold of a frog, and tie it alive to a new winnowing fan made of bamboo. On this fan, leaving the frog visible, they spread a few margosa leaves, and go singing from door to door ‘Lady frog must have her bath. Oh! rain-god, give a little water for her at least.’ This means that the drought has reached such a stage that there is not even a drop of water for the frogs. When the Kāpu woman sings this song, the woman of the house brings a little water in a vessel, pours it over the frog which is left on the fan outside the door, and gives some alms. The woman of the house is satisfied that such an action will soon bring down rain in torrents.”

In the Kāpu community, women play an important part, except in matters connected with agriculture. This is accounted for by a story to the effect that, when they came from Ayōdhya, the Kāpus brought no women with them, and sought the assistance of the gods in providing them with wives. They were told to marry women who were the illegitimate issue of Pāndavas, and the women consented on the understanding that they were to be given the upper hand, and that menial service, such as husking paddy (rice), cleaning vessels, and carrying water, should be done for them. They accordingly employ Gollas and Gamallas, and, in the Tamil country, Pallis as domestic servants. Mālas and Mādigas freely enter Kāpu houses for the purpose of husking paddy, but are not allowed into the kitchen, or room in which the household gods are worshipped.

In some Kāpu houses, bundles of ears of paddy may be seen hung up as food for sparrows, which are held in esteem. The hopping of sparrows is said to resemble the gait of a person confined in fetters, and there is a legend that the Kāpus were once in chains, and the sparrows set them at liberty, and took the bondage on themselves.

It has been noted by Mr. C. K. Subbha Rao, of the Agricultural Department, that the Reddis and others, who migrated southward from the Telugu country, “occupy the major portion of the black cotton soil of the Tamil country. There is a strange affinity between the Telugu cultivators and black cotton soil; so much so that, if a census was taken of the owners of such soil in the Tamil districts of Coimbatore, Trichinopoly, Madura, and Tinnevelly, ninety per cent, would no doubt prove to be Vadugars (northerners), or the descendants of Telugu immigrants. So great is the attachment of the Vadugan to the black cotton soil that the Tamilians mock him by saying that, when god offered paradise to the Vadugan, the latter hesitated, and enquired whether there was black cotton soil there.”

In a note on the Pongala or Pōkanāti and Panta Reddis of the Trichinopoly district, Mr. F. R. Hemingway writes as follows. “Both speak Telugu, but they differ from each other in their customs, live in separate parts of the country, and will neither intermarry nor interdine. The Reddis will not eat on equal terms with any other Sūdra caste, and will accept separate meals only from the vegetarian section of the Vellālas. They are generally cultivators, but they had formerly rather a bad reputation for crime, and it is said that some of them are receivers of stolen property. Like various other castes, they have beggars, called Bavani Nāyakkans, attached to them, who beg from no other caste, and whose presence is necessary when they worship their caste goddess.

The Chakkiliyans are also attached to them, and play a prominent part in the marriages of the Panta sub-division. Formerly, a Chakkiliyan was deputed to ascertain the status of the other party before the match was arranged, and his dreams were considered as omens of its desirability. He was also honoured at the marriage by being given the first betel and nuts. Nowadays he precedes the bridegroom’s party with a basket of fruit, to announce its coming. A Chakkiliyan is also often deputed to accompany a woman on a journey. The caste goddess of the Reddis is Yellamma, whose temple is at Esanai in Perambalūr, and she is reverenced by both Pantas and Pongalas. The latter observe rather gruesome rites, including the drinking of a kid’s blood. The Pantas also worship Rengayiamman and Pōlayamman with peculiar ceremonies. The women are the principal worshippers, and, on one of the nights after Pongal, they unite to do reverence to these goddesses, a part of the ritual consisting in exposing their persons. With this may be compared the Sevvaipillayar rite celebrated in honour of Ganēsa by Vellāla woman (see Vellāla). Both divisions of Reddis wear the sacred thread at funerals. Neither of them allow divorcées or widows to marry again.

The women of the two divisions can be easily distinguished by their appearance. The Panta Reddis wear a characteristic gold ear-ornament called kammal, a flat nose-ring studded with inferior rubies, and a golden wire round the neck, on which both the tāli and the pottu are tied. They are of fairer complexion than the Pongala women. The Panta women are allowed a great deal of freedom, which is usually ascribed to their dancing-girl origin, and are said to rule their husbands in a manner rare in other castes. They are often called dēvadiya (dancing-girl) Reddis, and it is said that, though the men of the caste receive hospitality from the Reddis of the north country, their women are not invited. Their chastity is said to be frail, and their lapses easily condoned by their husbands. The Pongalas are equally lax about their wives, but are said to rigorously expel girls or widows who misconduct themselves, and their seducers as well.

However, the Panta men and women treat each other with a courtesy that is probably to be found in no other caste, rising and saluting each other, whatever their respective ages, whenever they meet. The purification ceremony for a house defiled by the unchastity of a maid or widow is rather an elaborate affair. Formerly a Kolakkāran (huntsman), a Tottiyan, a priest of the village goddess, a Chakkiliyan, and a Bavani Nāyakkan had to be present. The Tottiyan is now sometimes dispensed with. The Kolakkāran and the Bavani Nāyakkan burn some kāmācchi grass (Andropogon Schœnanthus), and put the ashes in three pots of water. The Tottiyan then worships Pillayar (Ganēsa) in the form of some turmeric, and pours the turmeric into the water. The members of the polluted household then sit in a circle, while the Chakkiliyan carries a black kid round the circle. He is pursued by the Bavani Nāyakkan, and both together cut off the animal’s head, and bury it. The guilty parties have then to tread on the place where the head is buried, and the turmeric and ash water is poured over them. This ceremony rather resembles the one performed by the Ūrālis. The Pantas are said to have no caste panchāyats (council), whereas the Pongalas recognise the authority of officers called Kambalakkārans and Kottukkārans who uphold the discipline.”

The following are some of the proverbs relating to the Kāpus:—

The Kāpu protects all.

The Kāpu’s difficulties are known only to god.

The Kāpu dies from even the want of food.

The Kāpu knows not the distinction between daughter and daughter-in-law (i.e., both must work for him).

The Karnam (village accountant) is the cause of the Kāpu’s death.

The Kāpu goes not to the fort (i.e., into the presence of the Rāja). A modern variant is that the Kāpu goes not to the court (of law).

While the Kāpu was sluggishly ploughing, thieves stole the rope collars.

The year the Kāpu came in, the famine came too.

The Reddis are those who will break open the soil to fill their bellies.

When the unpracticed Reddi got into a palanquin, it swung from side to side.

The Reddi who had never mounted a horse sat with his face to the tail.

The Reddi fed his dog like a horse, and barked himself.