Lambādi

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Lambādi

The Lambādis are also called Lambāni, Brinjāri or Banjāri, Boipāri, Sugāli or Sukāli. By some Sugāli is said to be a corruption of supāri (betel nut), because they formerly traded largely therein. “The Banjarās,” Mr. G. A. Grierson writes, “are the well-known tribe of carriers who are found all over Western and Southern India. One of their principal sub-castes is known under the name of Labhānī, and this name (or some related one) is often applied to the whole tribe. The two names appear each under many variations, such as Banjāri, Vanjārī, Brinjārī, Labhāni, Labānī, Labānā, Lambādi, and Lambānī. The name Banjāra and its congeners is probably derived from the Sanskrit Vānijyakārakas, a merchant, through the Prakrit Vānijjaāraō, a trader. The derivation of Labhānī or Labānī, etc., is obscure. It has been suggested that it means salt carrier from the Sanskrit lavanah, salt, because the tribe carried salt, but this explanation goes against several phonetic rules, and does not account for the forms of the word like Labhānī or Lambānī. Banjārī falls into two main dialects—that of the Panjab and Gujarat, and that of elsewhere (of which we may take the Labhānī of Berar as the standard).

All these different dialects are ultimately to be referred to the language of Western Rajputana. The Labhānī of Berar possesses the characteristics of an old form of speech, which has been preserved unchanged for some centuries. It may be said to be based partly on Mārwāri and partly on Northern Gujarātī.” It is noted by Mr. Grierson that the Banjārī dialect of Southern India is mixed with the surrounding Dravidian languages. In the Census Report, 1901, Tanda (the name of the Lambādi settlements or camps), and Vāli Sugrīva are given as synonyms for the tribal name. Vāli and Sugrīva were two monkey chiefs mentioned in the Rāmāyana, from whom the Lambādis claim to be descended. The legend, as given by Mr. F. S. Mullaly, is that “there were two brothers, Mōta and Mōla, descendants of Sugrīva. Mōla had no issue, so, being an adept in gymnastic feats, he went with his wife Radha, and exhibited his skill at ‘Rathanatch’ before three rājahs. They were so taken with Mōla’s skill, and the grace and beauty of Radha, and of her playing of the nagāra or drum, that they asked what they could do for them. Mōla asked each of the rājahs for a boy, that he might adopt him as his son. This request was accorded, and Mōla adopted three boys.

Their names were Chavia, Lohia Panchar, and Ratāde. These three boys, in course of time, grew up and married. From Bheekya, the eldest son of Ratāde, started the clan known as the Bhutyas, and from this clan three minor sub-divisions known as the Maigavuth, Kurumtoths, and Kholas. The Bhutyas form the principal class among the Lambādis.” According to another legend, “one Chāda left five sons, Mūla, Mōta, Nathād, Jōgdā, and Bhīmdā. Chavān (Chauhān), one of the three sons of Mūla, had six sons, each of whom originated a clan. In the remote past, a Brāhman from Ajmir, and a Marāta from Jōtpur in the north of India, formed alliances with, and settled among these people, the Marāta living with Rathōl, a brother of Chavān. The Brāhman married a girl of the latter’s family, and his offspring added a branch to the six distinct clans of Chavān. These clans still retain the names of their respective ancestors, and, by reason of cousinship, intermarriage between some of them is still prohibited. They do, however, intermarry with the Brāhman offshoot, which was distinguished by the name of Vadtyā, from Chavān’s family. Those belonging to the Vadtyā clan still wear the sacred thread. The Marāta, who joined the Rathōl family, likewise founded an additional branch under the name of Khamdat to the six clans of the latter, who intermarry with none but the former. It is said that from the Khamdat clan are recruited most of the Lambādi dacoits.

The clan descended from Mōta, the second son of Chāda, is not found in the Mysore country. The descendants of Nathād, the third son, live by catching wild birds, and are known as Mirasikat, Paradi, or Vāgri (see Kuruvikkāran). The Jōgdās are people of the Jōgi caste. Those belonging to the Bhīmdā family are the peripatetic blacksmiths, called Bailu Kammāra. The Lambāni outcastes compose a sub-division called Thālya, who, like the Holayas, are drum-beaters, and live in detached habitations.”

As pointing to a distinction between Sukālis and Banjāris, it is noted by the Rev. J. Cain that “the Sukālīlu do not travel in such large companies as the Banjārīlu, nor are their women dressed as gaudily as the Banjāri women. There is but little friendship between these two classes, and the Sukāli would regard it as anything but an honour to be called a Banjāri, and the Banjāri is not flattered when called a Sukāli.” It is, however, noted, in the Madras Census Report, 1891, that enquiries show that Lambādis and Sugālis are practically the same. And Mr. H. A. Stuart, writing concerning the inhabitants of the North Arcot district, states that the names Sugāli, Lambādi and Brinjāri “seem to be applied to one and the same class of people, though a distinction is made. The Sugālis are those who have permanently settled in the district; the Lambādis are those who commonly pass through from the coast to Mysore; and the Brinjāris appear to be those who come down from Hyderabad or the Central Provinces.” It is noted by Mr. W. Francis that, in the Bellary district, the Lambādis do not recognise the name Sugāli.

Orme mentions the Lambādis as having supplied the Comte de Bussy with store, cattle and grain, when besieged by the Nizam’s army at Hyderabad. In an account of the Brinjāris towards the close of the eighteenth century, Moor writes that they “associate chiefly together, seldom or never mixing with other tribes. They seem to have no home, nor character, but that of merchants, in which capacity they travel great distances to whatever parts are most in want of merchandise, which is the greatest part corn. In times of war they attend, and are of great assistance to armies, and, being neutral, it is a matter of indifference to them who purchase their goods. They marched and formed their own encampments apart, relying on their own courage for protection; for which purpose the men are all armed with swords or matchlocks.

The women drive the cattle, and are the most robust we ever saw in India, undergoing a great deal of labour with apparent ease. Their dress is peculiar, and their ornaments are so singularly chosen that we have, we are confident, seen women who (not to mention a child at their backs) have had eight or ten pounds weight in metal or ivory round their arms and legs. The favourite ornaments appear to be rings of ivory from the wrist to the shoulder, regularly increasing in size, so that the ring near the shoulder will be immoderately large, sixteen or eighteen inches, or more perhaps in circumference. These rings are sometimes dyed red. Silver, lead, copper, or brass, in ponderous bars, encircle their shins, sometimes round, others in the form of festoons, and truly we have seen some so circumstanced that a criminal in irons would not have much more to incommode him than these damsels deem ornamental and agreeable trappings on a long march, for they are never dispensed with in the hottest weather.

A kind of stomacher, with holes for the arms, and tied behind at the bottom, covers their breast, and has some strings of cowries, depending behind, dangling at their backs. The stomacher is curiously studded with cowries, and their hair is also bedecked with them. They wear likewise ear-rings, necklaces, rings on the fingers and toes, and, we think, the nut or nose jewel. They pay little attention to cleanliness; their hair, once plaited, is not combed or opened perhaps for a month; their bodies or cloths are seldom washed; their arms are indeed so encased with ivory that it would be no easy matter to clean them. They are chaste and affable; any indecorum offered to a woman would be resented by the men, who have a high sense of honour on that head. Some are men of great property; it is said that droves of loaded bullocks, to the number of fifty or sixty thousand, have at different times followed the Bhow’s army.”

The Lambādis of Bellary “have a tradition among them of having first come to the Deccan from the north with Moghul camps as commissariat carriers. Captain J. Briggs, in writing about them in 1813, states that, as the Deccan is devoid of a single navigable river, and has no roads that admit of wheeled traffic, the whole of the extensive intercourse is carried on by laden bullocks, the property of the Banjāris.” Concerning the Lambādis of the same district, Mr. Francis writes that “they used to live by pack-bullock trade, and they still remember the names of some of the generals who employed their forebears. When peace and the railways came and did away with these callings, they fell back for a time upon crime as a livelihood, but they have now mostly taken to agriculture and grazing.” Some Lambādis are, at the present time (1908), working in the Mysore manganese mines.

Writing in 1825, Bishop Heber noted that “we passed a number of Brinjarees, who were carrying salt. They all had bows, arrows, sword and shield. Even the children had, many of them, bows and arrows suited to their strength, and I saw one young woman equipped in the same manner.”

Of the Lambādis in time of war, the Abbé Dubois inform us that “they attach themselves to the army where discipline is least strict. They come swarming in from all parts, hoping, in the general disorder and confusion, to be able to thieve with impunity. They make themselves very useful by keeping the market well supplied with the provisions that they have stolen on the march. They hire themselves and their large herds of cattle to whichever contending party will pay them best, acting as carriers of the supplies and baggage of the army. They were thus employed, to the number of several thousands, by the English in their last war with the Sultan of Mysore. The English, however, had occasion to regret having taken these untrustworthy and ill-disciplined people into their service, when they saw them ravaging the country through which they passed, and causing more annoyance than the whole of the enemy’s army.”

It is noted by Wilks that the travelling grain merchants, who furnished the English army under Cornwallis with grain during the Mysore war, were Brinjāris, and, he adds, “they strenuously objected, first, that no capital execution should take place without the sanction of the regular judicial authority; second, that they should be punishable for murder. The executions to which they demanded assent, or the murders for which they were called to account, had their invariable origin in witchcraft, or the power of communication with evil spirits. If a child sickened, or a wife was inconstant, the sorcerer was to be discovered and punished.”

It is recorded by the Rev. J. Cain that many of the Lambādis “confessed that, in former days, it was the custom among them before starting out on a journey to procure a little child, and bury it in the ground up to the shoulders, and then drive their loaded bullocks over the unfortunate victim, and, in proportion to their thoroughly trampling the child to death, so their belief in a successful journey increased. A Lambādi was seen repeating a number of mantrams (magical formulæ) over his patients, and touching their heads at the same time with a book, which was a small edition of the Telugu translation of St. John’s gospel. Neither the physician nor patient could read, and had no idea of the contents of the book.” At the time when human (meriah) sacrifices prevailed in the Vizagapatam Agency tracts, it was the regular duty of Lambādis to kidnap or purchase human beings in the plains, and sell them to the hill tribes for extravagant prices. A person, in order to be a fitting meriah, had to be purchased for a price.

It is recorded that not long after the accession of Vināyaka Deo to the throne of Jeypore, in the fifteenth century, some of his subjects rose against him, but he recovered his position with the help of a leader of Brinjāris. Ever since then, in grateful recognition, his descendants have appended to their signatures a wavy line (called valatradu), which represents the rope with which Brinjāris tether their cattle.

The common occupation of the Lambādis of Mysore is said to be “the transport, especially in the hill and forest tracts difficult of access, of grain and other produce on pack bullocks, of which they keep large herds. They live in detached clusters of rude huts, called thandas, at some distance from established villages. Though some of them have taken of late to agriculture, they have as yet been only partially reclaimed from criminal habits.” The thandas are said to be mostly pitched on high ground affording coigns of vantage for reconnoissance in predatory excursions. It is common for the Lambādis of the Vizagapatam Agency, during their trade peregrinations, to clear a level piece of land, and camp for night, with fires lighted all round them. Mr. C. Hayavadana Rao informs me that “they regard themselves as immune from the attacks of tigers, if they take certain precautions. Most of them have to pass through places infested with these beasts, and their favourite method of keeping them off is as follows. As soon as they encamp at a place, they level a square bit of ground, and light fires in the middle of it, round which they pass the night. It is their firm belief that the tiger will not enter the square, from fear lest it should become blind, and eventually be shot.

I was once travelling towards Malkangiri from Jeypore, when I fell in with a party of these people encamped in the manner described. At that time, several villages about Malkangiri were being ravaged by a notorious man-eater (tiger). In the Madras Census Reports the Lambādis are described as a class of traders, herdsmen, cattle-breeders, and cattle-lifters, found largely in the Deccan districts, in parts of which they have settled down as agriculturists. In the Cuddapah district they are said to be found in most of the jungly tracts, living chiefly by collecting firewood and jungle produce. In the Vizagapatam district, Mr. G. F. Paddison informs me, the bullocks of the Lambādis are ornamented with peacock’s feathers and cowry shells, and generally a small mirror on the forehead. The bullocks of the Brinjāris (Boiparis) are described by the Rev. G. Gloyer as having their horns, foreheads, and necks decorated with richly embroidered cloth, and carrying on their horns, plumes of peacock’s feathers and tinkling bells. When on the march, the men always have their mouths covered, to avoid the awful dust which the hundreds of cattle kick up. Their huts are very temporary structures made of wattle.

The whole village is moved about a furlong or so every two or three years—as early a stage of the change from nomadic to a settled life as can be found.” The Lambādi tents, or pāls, are said by Mr. Mullaly to be “made of stout coarse cloth fastened with ropes. In moving camp, these habitations are carried with their goods and chattels on pack bullocks.” Concerning the Lambādis of the Bellary district Mr. S. P. Rice writes to me as follows. “They are wood-cutters, carriers, and coolies, but some of them settle down and become cultivators. A Lambādi hut generally consists of only one small room, with no aperture except the doorway. Here are huddled together the men, women, and children, the same room doing duty as kitchen, dining and bedroom. The cattle are generally tied up outside in any available spot of the village site, so that the whole village is a sort of cattle pen interspersed with huts, in whatsoever places may have seemed convenient to the particular individual. Dotted here and there are a few shrines of a modest description, where I was told that fires are lighted every night in honour of the deity. The roofs are generally sloping and made of thatch, unlike the majority of houses in the Deccan, which are almost always terraced or flat roofed. I have been into one or two houses rather larger than those described, where I found a buffalo or two, after the usual Canarese fashion. There is an air of encampment about the village, which suggests a gipsy life.”

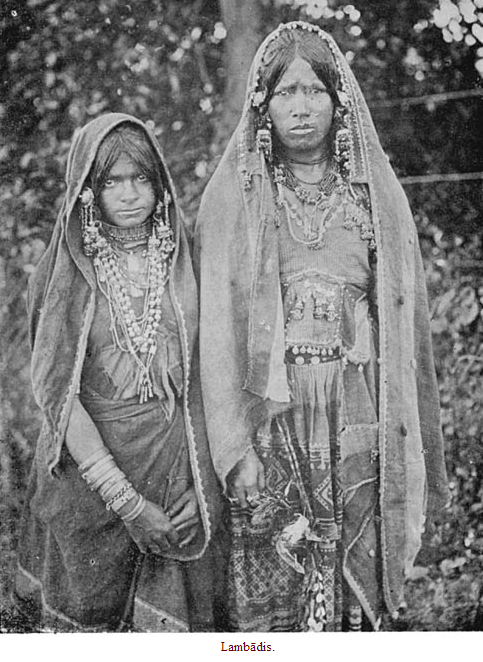

The present day costume and personal adornments of the Lambādi females have been variously described by different writers. By one, the women are said to remind one of the Zingari of Wallachia and the Gitani of Spain. “Married women,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, “are distinguished from the unmarried in that they wear their bangles between the elbow and shoulder, while the unmarried have them between the elbow and wrist. Unmarried girls may wear black bead necklets, which are taken off at marriage, at which time they first assume the ravikkai or jacket. Matrons also use an earring called guriki to distinguish them from widows or unmarried girls.” In the Mysore Census Report, 1901, it is noted that “the women wear a peculiar dress, consisting of a lunga or gown of stout coarse print, a tartan petticoat, and a mantle often elaborately embroidered, which also covers the head and upper part of the body. The hair is worn in ringlets or plaits hanging down each side of the face, and decorated with shells, and terminating in tassels. The arms are profusely covered with trinkets and rings made of bones, brass and other rude materials. The men’s dress consists of a white or red turband, and a pair of white breeches or knicker-bockers, reaching a little below the knee, with a string of red silk tassels hanging by the right side from the waistband.”

“The men,” Mr. F. S. Mullaly writes are fine muscular fellows, capable of enduring long and fatiguing marches. Their ordinary dress is the dhoty with short trousers, and frequently gaudy turbans and caps, in which they indulge on festive occasions. They also affect a considerable amount of jewellery. The women are, as a rule, comely, and above the average height of women of the country. Their costume is the laigna (langa) or gown of Karwar cloth, red or green, with a quantity of embroidery. The chola (choli) or bodice, with embroidery in the front and on the shoulders, covers the bosom, and is tied by variegated cords at the back, the ends of the cords being ornamented with cowries and beads. A covering cloth of Karwar cloth, with embroidery, is fastened in at the waist, and hangs at the side with a quantity of tassels and strings of cowries. Their jewels are very numerous, and include strings of beads of ten or twenty rows with a cowry as a pendant, called the cheed, threaded on horse-hair, and a silver hasali (necklace), a sign of marriage equivalent to the tāli. Brass or horn bracelets, ten to twelve in number, extending to the elbow on either arm, with a guzera or piece of embroidered silk, one inch wide, tied to the right wrist. Anklets of ivory (or bone) or horn are only worn by married women. They are removed on the death of the husband.

Pachala or silk embroidery adorned with tassels and cowries is also worn as an anklet by women. Their other jewels are mukaram or nose ornament, a silver kania or pendant from the upper part of the ear attached to a silver chain which hangs to the shoulder, and a profusion of silver, brass, and lead rings. Their hair is, in the case of unmarried women, unadorned, brought up and tied in a knot at the top of the head. With married women it is fastened, in like manner, with a cowry or a brass button, and heavy pendants or gujuris are fastened at the temples. This latter is an essential sign of marriage, and its absence is a sign of widowhood. Lambādi women, when carrying water, are fastidious in the adornment of the pad, called gala, which is placed on their heads. They cover it with cowries, and attach to it an embroidered cloth, called phūlia, ornamented with tassels and cowries.” I gather that Lambādi women of the Lavidia and Kimavath septs do not wear bracelets (chudo), because the man who went to bring them for the marriage of a remote ancestor died. In describing the dress of the Lambādi women, the Rev. G. N. Thomssen writes that “the sāri is thrown over the head as a hood, with a frontlet of coins dangling over the forehead. This frontlet is removed in the case of widows.

At the ends of the tufts of hair at the ears, heavy ornaments are tied or braided. Married women have a gold and silver coin at the ends of these tufts, while widows remove them. But the dearest possession of the women are large broad bracelets, made, some of wood, and the large number of bone or ivory. Almost the whole arm is covered with these ornaments. In case of the husband’s death, the bracelets on the upper arm are removed. They are kept in place by a cotton bracelet, gorgeously made, the strings of which are ornamented with the inevitable cowries. On the wrist broad heavy brass bracelets with bells are worn, these being presents from the mother to her daughter.” Each thanda, Mr. Natesa Sastri writes, has “a headman called the Nāyaka, whose word is law, and whose office is hereditary. Each settlement has also a priest, whose office is likewise hereditary.” According to Mr. H. A. Stuart, the thanda is named after the headman, and he adds, “the head of the gang appears to be regarded with great reverence, and credited with supernatural powers. He is believed to rule the gang most rigorously, and to have the power of life and death over its members.”

Concerning the marriage ceremonies of the Sugālis of North Arcot, Mr. Stuart informs us that these “last for three days. On the first an intoxicating beverage compounded of bhang (Cannabis indica) leaves, jaggery (crude sugar), and other things, is mixed and drunk. When all are merry, the bridegroom’s parents bring Rs. 35 and four bullocks to those of the bride, and, after presenting them, the bridegroom is allowed to tie a square silver bottu or tāli (marriage badge) to the bride’s neck, and the marriage is complete; but the next two days must be spent in drinking and feasting. At the conclusion of the third day, the bride is arrayed in gay new clothes, and goes to the bridegroom’s house, driving a bullock before her. Upon the birth of the first male child, a second silver bottu is tied to the mother’s neck, and a third when a second son is born. When a third is added to the family, the three bottus are welded together, after which no additions are made.” Of the Lambādi marriage ceremony in the Bellary district, the following detailed account is given by Mr. Francis.

“As acted before me by a number of both sexes of the caste, it runs as follows. The bridegroom arrives at night at the bride’s house with a cloth covering his head, and an elaborately embroidered bag containing betel and nut slung from his shoulder. Outside the house, at the four corners of a square, are arranged four piles of earthen pots—five pots in each. Within this square two grain-pounding pestles are stuck upright in the ground. The bride is decked with the cloth peculiar to married women, and taken outside the house to meet the bridegroom. Both stand within the square of pots, and round their shoulders is tied a cloth, in which the officiating Brāhman knots a rupee. This Brāhman, it may be at once noted, has little more to do with the ceremony beyond ejaculating at intervals ‘Shōbhana! Shōbhana!’ or ‘May it prosper!’ Then the right hands of the couple are joined, and they walk seven times round each of the upright pestles, while the women chant the following song, one line being sung for each journey round the pestle:

To yourself and myself marriage has taken place.

Together we will walk round the marriage pole.

Walk the third time; marriage has taken place.

You are mine by marriage.

Walk the fifth time; marriage has taken place.

Walk the sixth time; marriage has taken place.

Walk the seventh time; marriage has taken place.

We have walked seven times; I am yours.

Walk the seventh time; you are mine.

“The couple then sit on a blanket on the ground near one of the pestles, and are completely covered with a cloth. The bride gives the groom seven little balls compounded of rice, ghee (clarified butter) and sugar, which he eats. He then gives her seven others, which she in turn eats. The process is repeated near the other pestle. The women keep on chanting all the while. Then the pair go into the house, and the cloth into which the rupee was knotted is untied, and the ceremonies for that night are over. Next day the couple are bathed separately, and feasting takes place. That evening the girl’s mother or near female relations tie to the locks on each side of her temples the curious badges, called gugri, which distinguish a married from an unmarried woman, fasten a bunch of tassels to her back hair, and girdle her with a tasselled waistband, from which is suspended a little bag, into which the bridegroom puts five rupees. These last two are donned thereafter on great occasions, but are not worn every day. The next day the girl is taken home by her new husband.”

It is noted in the Mysore Census Report, 1891, that “one unique custom, distinguishing the Lambāni marriage ceremonial, is that the officiating Brāhman priest is the only individual of the masculine persuasion who is permitted to be present. Immediately after the betrothal, the females surround and pinch the priest on all sides, repeating all the time songs in their mixed Kutnī dialect. The vicarious punishment to which the solitary male Brāhman is thus subjected is said to be apt retribution for the cruel conduct, according to a mythological legend, of a Brāhman parent who heartlessly abandoned his two daughters in the jungle, as they had attained puberty before marriage. The pinching episode is notoriously a painful reality. It is said, however, that the Brāhman, willingly undergoes the operation in consideration of the fees paid for the rite.” The treatment of the Brāhman as acted before me by Lambādi women at Nandyāl, included an attempt to strip him stark naked. In the Census Report, it is stated that, at Lāmbadi weddings, the women “weep and cry aloud, and the bride and bridegroom pour milk into an ant-hill, and offer the snake which lives therein cocoanuts, flowers, and so on. Brāhmans are sometimes engaged to celebrate weddings, and, failing a Brāhman, a youth of the tribe will put on the thread, and perform the ceremony.”

The following variant of the marriage ceremonies was acted before me at Kadūr in Mysore. A pandal booth) is erected, and beneath it two pestles or rice-pounders are set up. At the four corners, a row of five pots is placed, and the pots are covered with leafy twigs of Calotropis procera, which are tied with Calotropis fibre or cotton thread. Sometimes a pestle is set up near each row of pots. The bridal couple seat themselves near the pestles, and the ends of their cloths, with a silver coin in them, are tied together. They are then smeared with turmeric, and, after a wave-offering to ward off the evil eye, they go seven times round the pestles, while the women sing:—

Oh! girl, walk along, walk.

You boasted that you would not marry.

Now you are married.

Walk, girl, walk on.

There is no good in your boasting.

You have eaten the pudding.

Walk, girl, walk.

Leave off boasting.

You sat on the plank with the bridegroom’s thigh on yours.

The bride and bridegroom take their seats on a plank, and the former throws a string round the neck of the latter, and ties seven knots in it. The bridegroom then does the same to the bride. The knots are untied. Cloths are then placed over the backs of the couple, and a swastika mark () is drawn on them with turmeric paste. A Brāhman purōhit is then brought to the pandal, and seats himself on a plank. A clean white cloth is placed on his head, and fastened tightly with string. Into this improvised turban, leafy twigs of mango and Cassia auriculata are stuck. Some of the Lambādi women present, while chanting a tune, throw sticks of Ficus glomerata, Artocarpus integrifolia, and mango in front of the Brāhman, pour gingelly (Sesamum) oil over them, and set them on fire. The Brāhman is made a bridegroom, and he must give out the name of his bride. He is then slapped on the cheeks by the women, thrown down, and his clothing stripped off. The Brāhman ceremonial concluded, a woman puts the badges of marriage on the bride. On the following day, she is dressed up, and made to stand on a bullock, and keep on crooning a mournful song, which makes her cry eventually. As she repeats the song, she waves her arms, and folds them over her head. The words of the song, the reproduction of which in my phonograph invariably made the women weep, are somewhat as follows:—

Oh! father, you brought me up so carefully by spending much money.

All this was to no purpose.

Oh! mother, the time has come when I have to leave you.

Is it to send me away that you nourished me?

Oh! how can I live away from you,

My brothers and sisters?

Among the Lambādis of Mysore, widow remarriage and polygamy are said to freely prevail, “and it is customary for divorced women to marry again during the lifetime of the husband under the sīrē udikē (tying of a new cloth) form of remarriage, which also obtains among the Vakkaligas and others. In such cases, the second husband, under the award of the caste arbitration, is made to pay a certain sum (tera) as amends to the first husband, accompanied by a caste dinner. The woman is then readmitted into society. But certain disabilities are attached to widow remarriage. Widows remarried are forbidden entry into a regular marriage party, whilst their offspring are disabled from legal marriage for three generations, although allowed to take wives from families similarly circumstanced.” According to Mr. Stuart, the Sugālis of the North Arcot district “do not allow the marriage of widows, but on payment of Rs. 15 and three buffaloes to her family, who take charge of her children, a widow may be taken by any man as a concubine, and her children are considered legitimate. Even during her husband’s life, a woman may desert him for any one else, the latter paying the husband the cost of the original marriage ceremony. The Sugālis burn the married, but bury all others, and have no ceremonies after death for the rest of the soul of the deceased.” If the head of a burning corpse falls off the pyre, the Lambādis pluck some grass or leaves, which they put in their mouths “like goats,” and run home.

A custom called Valli Sukkeri is recorded by the Rev. G. N. Thomssen, according to which “if an elder brother marries and dies without offspring, the younger brother must marry the widow, and raise up children, such children being regarded as those of the deceased elder brother. If, however, the elder brother dies leaving offspring, and the younger brother wishes to marry the widow, he must give fifteen rupees and three oxen to his brother’s children. Then he may marry the widow.” The custom here referred to is said to be practiced because the Lambādi’s ancestor Sugrīva married his elder brother Vali’s widow.

I am informed by Mr. F. A. Hamilton that, among the Lambādis of Kollegal in the Coimbatore district, “if a widower remarries, he may go through the ordinary marriage ceremony, or the kuttuvali rite, in which all that is necessary is to declare his selection of a bride to four or five castemen, whom he feeds. A widow may remarry according to the same rite, her new husband paying the expenses of the feast. Married people are burnt. Unmarried, and those who have been married by the kuttuvali rite, are buried. When cremation is resorted to, the eldest son sets fire to the funeral pyre. On the third day he makes a heap of the ashes, on which he sprinkles milk. He and his relations then return home, and hold a feast. When a corpse is buried, no such ceremonies are performed. Both males and females are addicted to heavy drinking. Arrack is their favourite beverage, and a Lambādi’s boast is that he spent so much on drink on such and such an occasion. The women dance and sing songs in eulogy of their goddess. At bed-time they strip off all their clothes, and use them as a pillow.”

The Lambādis are said to purchase children from other castes, and bring them up as their own. Such children are not allowed to marry into the superior Lambādi section called Thanda. The adopted children are classified as Koris, and a Kori may only marry a Lambādi after several generations.

Concerning the religion of the Lambādis, it is noted in the Mysore Census Report, 1891, that they are “Vishnuvaits, and their principal object of worship is Krishna. Bana Sankari, the goddess of forests, is also worshipped, and they pay homage to Basava on grounds dissimilar to those professed by the Lingayets. Basava is revered by the Lambādis because Krishna had tended cattle in his incarnation. The writer interviewed the chief Lambāni priests domiciled in the Holalkerē taluk. The priests belong to the same race, but are much less disreputable than the generality of their compatriots. It is said that they periodically offer sacrificial oblations in the agni or fire, at which a mantram is repeated, which may be paraphrased thus:—

I adore Bharma (Bramha) in the roots;

Vishnu who is the trunk;

Rudra (Mahadēv) pervading the branches;

And the Dēvās in every leaf.

“The likening of the Creator’s omnipotence to a tree among a people so far impervious to the traditions of Sanskrit lore may not appear very strange to those who will call to mind the Scandinavian tree of Igdrasil so graphically described by Carlyle, and the all-pervading Asvat’tha (pīpal) tree of the Bhagavatgīta.” It is added in the Mysore Census Report, 1901, that “the Lambānis own the Gosayis (Goswāmi) as their priests or gurus. These are the genealogists of the Lambānis, as the Helavas are of the Sīvachars.” Of the Sugālis of Punganūr and Palmanēr in the North Arcot district Mr. Stuart writes that “all worship the Tirupati Swāmi, and also two Saktis called Kōsa Sakti and Māni Sakti. Some three hundred years ago, they say that there was a feud between the Bukia and Mūdu Sugālis, and in a combat many were killed on both sides; but the widows of only two of the men who died were willing to perform sāti, in consequence of which they have been deified, and are now worshipped as saktis by all the divisions.”

It is said that, near Rolla in the Anantapur district, there is a small community of priests to the Lambādis who call themselves Muhammadans, but cannot intermarry with others of the faith, and that in the south-west of Madakasīra taluk there is another sub-division, called the Mondu Tulukar (who are usually stone-cutters and live in hamlets by themselves), who similarly cannot marry with other Musalmans. It is noted by the Rev. J. Cain that in some places the Lambādis “fasten small rags torn from some old garment to a bush in honour of Kampalamma (kampa, a thicket). On the side of one of the roads from Bastar are several large heaps of stones, which they have piled up in honour of the goddess Guttalamma. Every Lambādi who passes the heaps is bound to place one stone on the heap, and to make a salaam to it.” The goddess of the Lambādis of Kollegal is, according to Mr. Hamilton, Satthi. A silver image of a female, seated tailor-fashion, is kept by the head of the family, and is an heirloom. At times of festival it is set up and worshipped. Cooked food is placed before it, and a feast, with much arrack drinking, singing, beating of tom-tom, and dancing through the small hours of the night, is held. Examples of the Lambādi songs relating to incidents in the Rāmāyana, in honour of the goddesses Durga and Bhavāni, etc., have been published by Mr. F. Fawcett. The Brinjāris are described by the Rev. G. Gloyer as carrying their principal goddess “Bonjairini Mata,” on the horns of their cattle (leitochsen).

It is noted by the Rev. G. N. Thomssen that the Lambādis “worship the Supreme Being in a very pathetic manner. A stake, either a carved stick, or a peg, or a knife, is planted on the ground, and men and women form a circle round this, and a wild, weird chant is sung, while all bend very low to the earth. They all keep on circling about the stake, swinging their arms in despair, clasping them in prayer, and at last raising them in the air. Their whole cry is symbolic of the child crying in the night, the child crying for the light. If there are very many gathered together for worship, the men form one circle, and the women another. Another peculiar custom is their sacrifice of a goat or a chicken in case of removal from one part of the jungle to another, when sickness has come.

They hope to escape death by leaving one camping ground for another. Half-way between the old and new grounds, a chicken or goat is buried alive, the head being allowed to be above ground. Then all the cattle are driven over the buried creature, and the whole camp walk over the buried victim.” In former days, the Lambādis are reputed to have offered up human sacrifices. “When,” the Abbé Dubois writes, “they wish to perform this horrible act, it is said, they secretly carry off the first person they meet. Having conducted the victim to some lonely spot, they dig a hole, in which they bury him up to the neck. While he is still alive, they make a sort of lump of dough made of flour, which they place on his head. This they fill with oil, and light four wicks in it. Having done this, the men and women join hands, and, forming a circle, dance round their victim, singing and making a great noise, till he expires.” The interesting fact is recorded by Mr. Mullaly “that, before the Lambādis proceed on a predatory excursion, a token, usually a leaf, is secreted in some hidden place before proceeding to invoke Durga. The Durgamma pūjāri (priest), one of their own class, who wears the sacred thread, and is invested with his sacred office by reason of his powers of divination, lights a fire, and, calling on the goddess for aid, treads the fire out, and names the token hidden by the party. His word is considered an oracle, and the pūjāri points out the direction the party is to take.”

From a further note on the religion of the Lambādis, I gather that they worship the following:—

• (1) Balaji, whose temple is at Tirupati. Offerings of money are made to this deity for the bestowal of children, etc. When their prayers are answered, the Lambādis walk all the way to Tirupati, and will not travel thither by railway.

• (2) Hanumān, the monkey god.

• (3) Poleramma. To ward off devils and evil spirits.

• (4) Mallalamma. To confer freedom to their cattle from attacks of tigers and other wild beasts.

• (5) Ankalamma. To protect them from epidemic disease.

• (6) Peddamma.

• (7) Maremma.

The Lambādis observe the Holi festival, for the celebration of which money is collected in towns and villages. On the Holi day, the headman and his wife fast, and worship two images of mud, representing Kama (the Indian cupid) and his wife Rati. On the following morning, cooked food is offered to the images, which are then burnt. Men and women sing and dance, in separate groups, round the burning fire. On the third day, they again sing and dance, and dress themselves in gala attire. The men snatch the food which has been prepared by the women, and run away amid protests from the women, who sometimes chastise them.

It is narrated by Moor that “he passed a tree, on which were hanging several hundred bells. This was a superstitious sacrifice by the Bandjanahs, who, passing this tree, are in the habit of hanging a bell or bells upon it, which they take from the necks of their sick cattle, expecting to leave behind them the complaint also. Our servants particularly cautioned us against touching these diabolical bells; but, as a few were taken for our own cattle, several accidents that happened were imputed to the anger of the deity, to whom these offerings were made, who, they say, inflicts the same disorder on the unhappy bullock who carries a bell from this tree as he relieved the donor from.” There is a legend in connection with the matsya gundam (fish pool) close under the Yendrika hill in the Vizagapatam district. The fish therein are very tame, and are protected by the Mādgole Zamindars. “Once, goes the story, a Brinjāri caught one and turned it into curry, whereon the king of the fish solemnly cursed him, and he and all his pack-bullocks were turned into rocks, which may be seen there to this day.”

Lambādi women often have elaborate tattooed patterns on the backs of the hands, and a tattooed dot on the left side of the nose may be accepted as a distinguishing character of the tribe in some parts. My assistant once pointed out that, in a group of Lambādis, some of the girls did not look like members of the tribe. This roused the anger of an old woman, who said “You can see the tattoo marks on the nose, so they must be Lambādis.”

Lambādi women will not drink water from running streams or big tanks.

In the Mysore Province, there is a class of people called Thambūri, who dress like Lambādis, but do not intermarry with them. They are Muhammadans, and their children are circumcised. Their marriages are carried out according to the Muhammadan nikka rite, but they also go through the Lambādi form of marriage, except that marriage pots are not placed in the pandal [232](wedding booth). The Lambādis apparently pay some respect to them, and give them money at marriages or on other occasions. They seem to be bards and panegyrists of the Lambādis, in the same way that other classes have their Nōkkans, Vīramushtis, Bhatrāzus, etc. It is noted by Mr. Stuart33 that the Lambādis have priests called Bhats, to whom it is probable that the Thambūris correspond in Mysore.

The methods of the criminal Lambādis are dealt with at length by Mr. Mullaly. And it must suffice for the present purpose to note that they commit dacoities and have their receivers of stolen property, and that the Naik or headman of the gang takes an active share