North-Eastern India: developmental indicators

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

North-Eastern India: developmental indicators

Only Time Northeast Takes Centre Stage

Day Before Polls In Assam & Tripura, TOI Looks At How Dependent NE Is On Centre But Matters Little To It

Subodh Varma | TIG The Times of India

With only 25 MPs representing eight states, the Northeast doesn’t matter as much for poll pundits and party strategists dabbling in the national calculus. These eight states are sparsely populated with just 4% of India’s population spread over 8% of India’s land area, mostly hilly and forested.

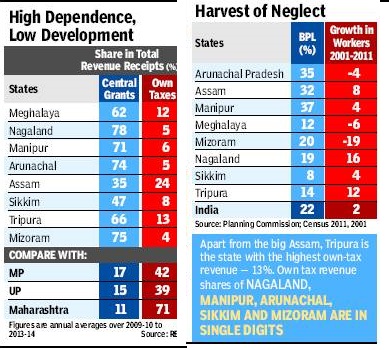

Two forces, often at odds with each other, determine the region’s complex politics. One is ethnic or regional aspirations and the other is their relationship with the Centre. Politics and governance is highly dependent on central largesse. In Nagaland and Mizoram over three quarters of the state’s revenue receipts (income) comes from central grants. The situation is similar in other NE states. Only in Assam, the largest of the NE states having more than two thirds of the population of the region, does the share of central grants drop to 35%.

The other side of the coin is that their own tax generation is very low. Apart from the big Assam, Tripura is the state with the highest own-tax revenue — 13%. Own-tax revenue shares of Nagaland, Manipur, Arunachal, Sikkim and Mizoram are in single digits.

In comparison, Maharashtra gets 11% of its revenue from central grants and as an advanced state raises 71% revenue through its own taxes. Relatively poorer states like Madhya Pradesh and UP get 15%-17% revenue from the Centre, raising 40% resources through own taxes.

But shouldn’t this huge flow of public funds have generated more jobs, better infrastructure over the decades? In three states, including Assam, those below poverty line number more than a third of the state’s population. In two others, every fifth person is BPL. Just Tripura, Meghalaya and tiny Sikkim have poverty ratios below 15%. This, using the very low poverty line fi xed by the Planning Commission.

Jobs: In Arunachal, Meghalaya and Mizoram, total number of workers actually declined between 2001 and 2011, discounting increases from population growth. Lack of industrialization or services sector growth has forced the region to remain bound to subsistence agriculture.