Palli or Vanniyan

This article is an excerpt from Government Press, Madras |

Palli or Vanniyan

Writing concerning this caste the Census Superintendent, 1871, records that “a book has been written by a native to show that the Pallis (Pullies or Vanniar) of the south are descendants of the fire races (Agnikulas) of the Kshatriyas, and that the Tamil Pullies were at one time the shepherd kings of Egypt.” At the time of the census, 1871, a petition was submitted to Government by representatives of the caste, praying that they might be classified as Kshatriyas, and twenty years later, in connection with the census, 1891, a book entitled ‘Vannikula Vilakkam: a treatise on the Vanniya caste,’ was compiled by Mr. T. Aiyakannu Nayakar, in support of the caste claim to be returned as Kshatriyas, for details concerning which claim I must refer the reader to the book itself. In 1907, a book entitled Varuna Darpanam (Mirror of Castes) was published, in which an attempt is made to connect the caste with the Pallavas.

Kulasēkhara, one of the early Travancore kings, and one of the most renowned Ālwars reverenced by the Srī Vaishnava community in Southern India, is claimed by the Pallis as a king of their caste. Even now, at the Parthasārathi temple in Triplicane (in the city of Madras), which according to inscriptions is a Pallava [2]temple, Pallis celebrate his anniversary with great éclat. The Pallis of Kōmalēsvaranpettah in the city of Madras have a Kulasēkhara Perumāl Sabha, which manages the celebration of the anniversary. The temple has recently been converted at considerable cost into a temple for the great Ālwar. A similar celebration is held at the Chintādripettah Ādikēsava Perumāl temple in Madras. The Pallis have the right to present the most important camphor offering of the Mylapore Siva temple. They allege that the temple was originally theirs, but by degrees they lost their hold over it until this bare right was left to them. Some years ago, there was a dispute concerning the exercise of this right, and the case came before the High Court of Madras, which decided the point at issue in favour of the Pallis. One of the principal gōpuras (pyramidal towers) of the Ēkāmranātha temple at Big Conjeeveram, the ancient capital of the Pallavas, is known as Palligōpuram. The Pallis of that town claim it as their own, and repair it from time to time. In like manner, they claim that the founder of the Chidambaram temple, by name Swēta Varman, subsequently known as Hiranya Varman (sixth century A.D.) was a Pallava king.

At Pichavaram, four miles east of Chidambaram, lives a Palli family, which claims to be descended from Hiranya Varman. A curious ceremony is even now celebrated at the Chidambaram temple, on the steps leading to the central sanctuary. As soon as the eldest son of this family is married, he and his wife, accompanied by a local Vellāla, repair to the sacred shrine, and there, amidst crowds of their castemen and others, a hōmam (sacrificial fire) is raised, and offerings are made to it. The couple are then anointed with nine different kinds of holy water, and the Vellāla places the temple crown on their heads. The Vellāla who officiates at this ceremony, assisted by the temple priests, is said to belong to the family of a former minister of a descendant of Hiranya Varman. It is said that, as the ceremony is a costly one, and the expenses have to be paid by the individual who undergoes it, it often happens that the eldest son of the family has to remain a bachelor for half his lifetime. The Pallis who reside at St. Thomé in the city of Madras allege that they became Christians, with their King Kandappa Rāja, who, they say, ruled over Mylapore during the time of the visit of St. Thomas. In 1907, Mr. T. Varadappa Nayakar, the only High Court Vakil (pleader) among the Palli community practising in Madras, brought out a Tamil book on the history of the connection of the caste with the ancient Pallava kings.

In reply to one of a series of questions promulgated by the Census Superintendent, it was stated that “the caste is known by the following names:—Agnikulas and Vanniyas. The etymology of these is the same, being derived from the Sanskrit Agni or Vahni, meaning fire. The following, taken from Dr. Oppert’s article on the original inhabitants of Bharatavarsa or India, explains the name of the caste with its etymology:—‘The word Vanniyan is generally derived from the Sanskrit Vahni, fire. Agni, the god of fire, is connected with regal office, as kings hold in their hands the fire-wheel or Agneya-chakra, and the Vanniyas urge in support of their name the regal descent they claim.’ The existence of these fire races, Agnikula or Vahnikula (Vanniya), in North and South India is a remarkable fact. No one can refuse to a scion of the non-Aryan warrior tribe the title of Rajputra, but in so doing we establish at once Aryan and non-Aryan Rajaputras or Rajputs.

The Vanniyan of South India may be accepted as a representative of the non-Aryan Rajput element.” The name Vanniyan is, Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, “derived from the Sanskrit vanhi (fire) in consequence of the following legend. In the olden times, two giants named Vātāpi and Māhi, worshipped Brahma with such devotion that they obtained from him immunity from death from every cause save fire, which element they had carelessly omitted to include in their enumeration. Protected thus, they harried the country, and Vātāpi went the length of swallowing Vāyu, the god of the winds, while Māhi devoured the sun. The earth was therefore enveloped in perpetual darkness and stillness, a condition of affairs which struck terror into the minds of the dēvatas, and led them to appeal to Brahma. He, recollecting the omission made by the giants, directed his suppliants to desire the rishi Jāmbava Mahāmuni to perform a yāgam, or sacrifice by fire. The order having been obeyed, armed horse men sprung from the flames, who undertook twelve expeditions against Vātāpi and Māhi, whom they first destroyed, and afterwards released Vāyu and the sun from their bodies. Their leader then assumed the government of the country under the name Rūdra Vanniya Mahārāja, who had five sons, the ancestors of the Vanniya caste. These facts are said to be recorded in the Vaidīswara temple in the Tanjore district.”

The Vaidīswara temple here referred to is the Vaidīswara kōvil near Shiyāli. Mr. Stuart adds that “this tradition alludes to the destruction of the city of Vāpi by Narasimha Varma, king of the Pallis or Pallavas.” Vāpi, or Vā-api, was the ancient name of Vātāpi or Bādāmi in the Bombay Presidency. It was the capital of the Chālukyas, who, during the seventh century, were at feud with the Pallavas of the south. “The son of Mahēndra Varman I,” writes Rai Bahadur V. Venkayya, “was Narasimha Varman I, who retrieved the fortunes of the family by repeatedly defeating the Chōlas, Kēralas, Kalabhras, and Pāndyas. He also claims to have written the word victory as on a plate on Pulikēsin’s back, which was caused to be visible (i.e., which was turned in flight after defeat) at several battles. Narasimha Varman carried the war into Chālukyan territory, and actually captured Vātāpi their capital.

This claim of his is established by an inscription found at Bādāmi, from which it appears that Narasimha Varman bore the title Mahāmalla. In later times, too, this Pallava king was known as Vātāpi Konda Narasingapottaraiyan. Dr. Fleet assigns the capture of the Chālukya capital to about A.D. 642. The war of Narasimha Varman with Pulikēsin is mentioned in the Sinhalese chronicle Mahāvamsa. It is also hinted at in the Tamil Periyapurānam. The well-known saint Siruttonda, who had his only son cut up and cooked in order to satisfy the appetite of the god Siva disguised as a devotee, is said to have reduced to dust the city of Vātāpi for his royal master, who could be no other than the Pallava king Narasimha Varman.” I gather, from a note by Mr. F. R. Hemingway, that the Pallis “tell a long story of how they are descendants of one Vīra Vanniyan, who was created by a sage named Sambuha when he was destroying the two demons named Vātāpi and Enatāpi. This Vīra Vanniyan married a daughter of the god Indra, and had five sons, named Rūdra, Brahma, Krishna, Sambuha, and Kai, whose descendants now live respectively in the country north of the Pālār in the Cauvery delta, between the Pālār and Pennar. They have written a Purānam and a drama bearing on this tale. They declare that they are superior to Brāhmans, since, while the latter must be invested with the sacred thread after birth, they bring their sacred thread with them at birth itself.”

“The Vanniyans,” Mr. Nelson states, “are at the present time a small and obscure agricultural caste, but there is reason to believe that they are descendants of ancestors who, in former times, held a good position among the tribes of South India. A manuscript, abstracted at page 90 of the Catalogue raisonné (Mackenzie Manuscripts), states that the Vanniyans belong to the Agnikula, and are descended from the Muni Sambhu; and that they gained victories by means of their skill in archery. And another manuscript, abstracted at page 427, shows that two of their chiefs enjoyed considerable power, and refused to pay the customary tribute to the Rayar, who was for a long time unable to reduce them to submission. Armies of Vanniyans are often mentioned in Ceylon annals. And a Hindu History of Ceylon, translated in the Royal As. Soc. Journal, Vol. XXIV, states that, in the year 3300 of the Kali Yuga, a Pandya princess went over to Ceylon, and married its king, and was accompanied by sixty bands of Vanniyans.”

The terms Vanni and Vanniyan are used in Tamil poems to denote king. Thus, in the classical Tamil poem Kallādam, which has been attributed to the time of Tiruvalluvar, the author of the sacred Kural, Vanni is used in the sense of king. Kamban, the author of the Tamil Rāmāyana, uses it in a similar sense. In an inscription dated 1189 A.D., published by Dr. E. Hultzsch, Vanniya Nāyan appears among the titles of the local chief of Tiruchchūram, who made a grant of land to the Vishnu temple at Manimangalam. Tiruchchūram is identical with Tiruvidaichūram about four miles south-east of Chingleput, where there is a ruined fort, and also a Siva temple celebrated in the hymns of Tirugnāna Sambandhar, the great Saiva saint who lived in the 9th century. Local tradition, confirmed by one of the Mackenzie manuscripts, says that this place was, during the time of the Vijayanagar King Krishna Rāya (1509–30 A.D.), ruled over by two feudal chiefs of the Vanniya caste named Kāndavarāyan and Sēndavarāyan.

They, it is said, neglected to pay tribute to their sovereign lord, who sent an army to exact it. The brothers proved invincible, but one of their dancing-girls was guilty of treachery. Acting under instructions, she poisoned Kāndavarāyan. His brother Sēndavarāyan caught hold of her and her children, and drowned them in the local tank. The tank and the hillock close by still go by the name of Kuppichi kulam and Kuppichi kunru, after Kuppi the dancing-girl. An inscription of the Vijayanagar king Dēva Rāya II (1419–44 A.D.) gives him the title of the lord who took the heads of the eighteen Vanniyas. This inscription records a grant by one Muttayya Nāyakan, son of Mūkkā Nāyakan of Vannirāya gōtram. Another inscription, dated 1456 A.D., states that, when one Rāja Vallabha ruled at Conjeeveram, a general, named Vanniya Chinna Pillai, obtained a piece of land at Sāttānkād near Madras. Reference is made by Orme to the assistance which the Vaniah of Sevagherry gave Muhammad Yūsuf in his reduction of Tinnevelly in 1757. The Vaniah here referred to is the Zamindar of Sivagiri in the Tinnevelly district, a Vanniya by caste. Vanniyas are mentioned in Ceylon archives. Wanni is the name of a district in Ceylon. It is, Mr. W. Hamilton writes, “situated towards Trincomalee in the north-east quarter. At different periods its Wannies or princes, taking advantage of the wars between the Candian sovereigns and their European enemies, endeavoured to establish an authority independent of both, but they finally, after their country had been much desolated by all parties, submitted to the Dutch.” Further, Sir J. E. Tennent writes, that “in modern times, the Wanny was governed by native princes styled Wannyahs, and occasionally by females with the title of Wunniches.”

The terms Sambhu and Sāmbhava Rāyan are connected with the Pallis. The story goes that Agni was the original ancestor of all kings. His son was Sambhu, whose descendants called themselves Sambhukula, or those of the Sambhu family. Some inscriptions of the time of the Chōla kings Kulōttunga III and Rāja Rāja III record Sambukula Perumāl Sāmbuvarāyan and Alagiya Pallavan Ēdirili Sōla Sāmbuvarāyan as titles of local chiefs. A well-known verse of Irattayar in praise of Conjeeveram Ēkāmranāthaswāmi refers to the Pallava king as being of the Sambu race. The later descendants of the Pallavas apparently took Sāmbuvarāyar and its allied forms as their titles, as the Pallis in Tanjore and South Arcot still do. At Conjeeveram there lives the family of the Mahānāttār of the Vanniyans, which calls itself “of the family of Vīra Sambu.”

“The name Vanniyan,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes, seems to have been introduced by the Brāhmans, possibly to gratify the desire of the Pallis for genealogical distinction. Padaiyāchi means a soldier, and is also of late origin. That the Pallis were once an influential and independent community may be admitted, and in their present desire to be classed as Kshatriyas they are merely giving expression to this belief, but, unless an entirely new meaning is to be given to the term Kshatriya, their claim must be dismissed as absurd. After the fall of the Pallava dynasty, the Pallis became agricultural servants under the Vellālas, and it is only since the advent of British rule that they have begun to assert their claims to a higher position.” Further, Mr. W. Francis writes that “this caste has been referred to as being one of those which are claiming for themselves a position higher than that which Hindu society is inclined to accord them. Their ancestors were socially superior to themselves, but they do not content themselves with stating this, but in places are taking to wearing the sacred thread of the twice-born, and claim to be Kshatriyas.

They have published pamphlets to prove their descent from that caste, and they returned themselves in thousands, especially in Godāvari, as Agnikula Kshatriyas or Vannikula Kshatriyas, meaning Kshatriyas of the fire race.” “As a relic,” it has been said, “of the origin of the Vannikula Kshatriyas from fire, the fire-pot, which comes in procession on a fixed day during the annual festivities of Draupadi and other goddesses, is borne on the head of a Vanniya. Also, in dramatic plays, the king personæ (sic) has always been taken by a Kshatriya, who is generally a Vanniya. These peculiarities, however, are becoming common now-a-days, when privileges peculiar to one caste are being trenched upon by other caste men. In the Tirupporur temple, the practice of beating the mazhu (red-hot iron) is done by a dancing-girl serving the Vanniya caste. The privilege of treading on the fire is also peculiar to the Vanniyas.” It is recorded by Mr. Francis that, in the South Arcot district, “Draupadi’s temples are very numerous, and the priest at them is generally a Palli by caste, and Pallis take the leading part in the ceremonies at them. Why this should be so is not clear. The Pallis say it is because both the Pāndava brothers and themselves were born of fire, and are therefore related. Festivals to Draupadi always involve two points of ritual—the recital or acting of a part of the Mahābhārata and a fire-walking ceremony. The first of these is usually done by the Pallis, who are very fond of the great epic, and many of whom know it uncommonly well. [In the city of Madras there are several Draupadi Amman temples belonging to the Pallis. The fire-walking ceremony cannot be observed thereat without the help of a member of this caste, who is the first to walk over the hot ashes.

Kūvvākkam is known for its festival to Aravān (more correctly Irāvān) or Kūttāndar, which is one of the most popular feasts with Sūdras in the whole district. Aravān was the son of Arjuna, one of the five Pāndava brothers. Local tradition says that, when the great war which is described in the Mahābhārata was about to begin, the Kauravas, the opponents of the Pāndavas, sacrificed, to bring them success, a white elephant. The Pāndavas were in despair of being able to find any such uncommon object with which to propitiate the gods, until Arjuna suggested that they should offer up his son Aravān. Aravān agreed to yield his life for the good of the cause, and, when eventually the Pāndavas were victorious, he was deified for the self-abnegation which had thus brought his side success. Since he died in his youth, before he had been married, it is held to please him if men, even though grown up and already wedded, come now and offer to espouse him, and men who are afflicted with serious diseases take a vow to marry him at his annual festival in the hope of thereby being cured. The festival occurs in May, and for eighteen nights the Mahābhārata is recited by a Palli, large numbers of people, especially of that caste, assembling to hear it read.

On the eighteenth night, a wooden image of Kūttāndar is taken to a tope (grove), and seated there. This is the signal for the sacrifice of an enormous number of fowls. Every one who comes brings one or two, and the number killed runs literally into thousands. Such sacrifices are most uncommon in South Arcot, though frequent enough in other parts of the Presidency—the Ceded Districts for example—and this instance is noteworthy. While this is going on, all the men who have taken vows to be married to the deity appear before his image dressed like women, make obeisance, offer to the priest (who is a Palli by caste) a few annas, and give into his hands the tālis (marriage badges) which they have brought with them. These the priest, as representing the God, ties round their necks. The God is brought back to his shrine that night, and when in front of the building he is hidden by a cloth being held before him. This symbolises the sacrifice of Aravān, and the men who have just been married to him set up loud lamentations at the death of their husband. Similar vows are taken and ceremonies performed, it is said, at the shrines to Kūttāndar at Kottattai (two miles north-west of Porto Novo), and Ādivarāhanattum (five miles north-west of Chidambaram), and, in recent years, at Tiruvarkkulam (one mile east of the latter place); other cases probably occur.”

The Pallis, Mr. Francis writes further, “as far back as 1833 tried to procure a decree in Pondicherry, declaring that they were not a low caste, and of late years they have, in this (South Arcot) district, been closely bound together by an organisation managed by one of their caste, who was a prominent person in these parts. In South Arcot they take a somewhat higher social rank than in other places—Tanjore, for example—and their esprit de corps is now surprisingly strong. They are tending gradually to approach the Brāhmanical standard of social conduct, discouraging adult marriage, meat-eating, and widow re-marriage, and they also actively repress open immorality or other social sins, which might serve to give the community a bad name. In 1904 a document came before one of the courts, which showed that, in the year previous, the representatives of the caste in thirty-four villages in this district had bound themselves in writing, under penalty of excommunication, to refrain (except with the consent of all parties) from the practices formerly in existence of marrying two wives, and of allowing a woman to marry again during the lifetime of her first husband. Some of the caste have taken to calling themselves Vannikula Kshatriyas or Agnikula Kshatriyas, and others even declare that they are Brāhmans. These last always wear the sacred thread, tie their cloths in the Brāhman fashion (though their women do not follow the Brāhman ladies in this matter), forbid widow remarriage, and are vegetarians.”

Some Palli Poligars have very high-sounding names, such as Agni Kudirai Eriya Rāya Rāvutha Minda Nainar, i.e., Nainar who conquered Rāya Rāvutha and mounted a fire horse. This name is said to commemorate a contest between a Palli and a Rāvutha, at which the former sat on a red-hot metal horse. Further names are Sāmidurai Surappa Sozhaganar and Anjāda Singam (fearless lion). Some Pallis have adopted Gupta as a title. A few Palli families now maintain a temple of their own, dedicated to Srīnivāsa, at the village of Kumalam in the South Arcot district, live round the temple, and are largely dependent on it for their livelihood. Most of them dress exactly like the temple Battars, and a stranger would certainly take them for Battar Brāhmans. Some of them are well versed in the temple ritual, and their youths are being taught the Sandyavandhana (morning prayer) and Vēdas by a Brāhman priest. Ordinary Palli girls are taken by them in marriage, but their own girls are not allowed to marry ordinary Pallis; and, as a result of this practice of hypergamy, the Kumalam men sometimes have to take to themselves more than one wife, in order that their young women may be provided with husbands. These Kumalam Pallis are regarded as priests of the Pallis, and style themselves Kōvilar, or temple people. But, by other castes, they are nicknamed Kumalam Brāhmans. They claim to be Kshatriyas, and have adopted the title Rāyar.

Other titles, “indicating authority, bravery, and superiority,” assumed by Pallis are Nāyakar, Varma, Padaiyāchi (head of an army), Kandar, Chēra, Chōla, Pāndya, Nayanar, Udaiyar, Samburāyar, etc. Still further titles are Pillai, Reddi, Goundan, and Kavandan. Some say that they belong to the Chōla race, and that, as such, they should be called Chembians. Iranya Varma, the name of one of the early Pallava kings, was returned as their caste by certain wealthy Pallis, who also gave themselves the title of Sōlakanar (descendant of Chōla kings) at the census, 1901.

In reply to a question by the Census Superintendent, 1891, as to the names of the sub-divisions of the caste, it was stated that “the Vanniyans are either of the solar and lunar or Agnikula race, or Ruthra Vanniyar, Krishna Vanniyar, Samboo Vanniyar, Brahma Vanniyar, and Indra Vanniyar.” The most important of the sub-divisions returned at the census were Agamudaiyan, Agni, Arasu (Rāja), Kshatriya, Nāgavadam (cobra’s hood, or ear ornament of that shape), Nattamān, Ōlai (palm leaf), Pandamuttu, and Perumāl gōtra. Pandamuttu is made by Winslow to mean torches arranged so as to represent an elephant. But the Pallis derive the name from panda muttu, or touching the pandal, in reference to the pile of marriage pots reaching to the top of the pandal. The lowest pot is decorated with figures of elephants and horses. At a marriage among the Pandamuttu Pallis, the bride and bridegroom, in token of their Kshatriya descent, are seated on a raised dais, which represents a simhāsanam or throne. The bride wears a necklace of glass beads with the tāli, and the officiating priest is a Telugu Brāhman. Other sub-castes of the Pallis, recorded in the Census Report, 1901, are Kallangi in Chingleput, bearing the title Reddi, and Kallavēli, or Kallan’s fence, in the Madura district. The occupational title Kottan (bricklayer) was returned by some Pallis in Coimbatore. In the Salem district some Pallis are divided into Anju-nāl (five days) and Pannendū-nāl (twelve days), according as they perform the final death ceremonies on the fifth or twelfth day after death, to distinguish them from those who perform them on the sixteenth day.19 Another division of Pallis in the Salem district is based on the kind of ear ornament which is worn. The Ōlai Pallis wear a circular ornament (ōlai), and the Nāgavadam Pallis wear an ornament in shape like a cobra and called nāgavadam.

The Pallis are classed with the left-hand section. But the Census Superintendent, 1871, records that “the wives of the agricultural labourers (Pallis) side with the left hand, while the husbands help in fighting the battles of the right; and the shoe-makers’ (Chakkiliyan) wives also take the side opposed to their husbands. During these factional disturbances, the ladies deny to their husbands all the privileges of the connubial state.” This has not, however, been confirmed in recent investigations into the customs of the caste.

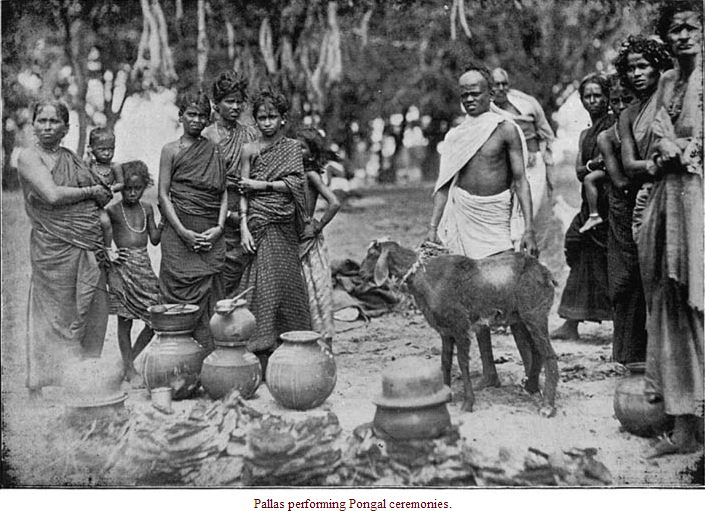

The Pallis are Saivites or Vaishnavites, but are also demonolaters, and worship Mutyālamma, Māriamma, Ayanar, Munēswara, Ankālamma, and other minor deities. Writing nearly a century ago concerning the Vana Pallis settled at Kolar in Mysore, Buchanan states that “they are much addicted to the worship of the saktis, or destructive powers, and endeavour to avert their wrath by bloody sacrifices. These are performed by cutting off the animal’s head before the door of the temple, and invoking the deity to partake of the sacrifice. There is no altar, nor is the blood sprinkled on the image, and the body serves the votaries for a feast. The Pallivānlu have temples dedicated to a female spirit of this kind named Mutialamma, and served by pūjāris (priests) of their own caste. They also offer sacrifices to Māriamma, whose pūjāris are Kurubaru.”

Huge human figures, representing Mannarswāmi in a sitting posture, constructed of bricks and mortar, and painted, are conspicuous objects in the vicinity of the Lawrence Asylum Press, Mount Road, and in the Kottawāl bazar, Madras. At the village of Tirumalavāyal near Āvadi, there is a similar figure as tall as a palmyra palm, with a shrine of Pachaiamman close by. Mannarswāmi is worshipped mainly by Pallis and Bēri Chettis. An annual festival is held in honour of Pachaiamman and Mannarswāmi, in which the Bēri Chettis take a prominent part.

During the festivals of village deities, the goddess is frequently represented by a pile of seven pots, called karagam, decorated with garlands and flowers. Even when there is an idol in the temple, the karagam is set up in a corner thereof, and taken daily, morning and evening, in procession, carried on the head of a pūjāri or other person. On the last day of the festival, the karagam is elaborately decorated with parrots, dolls, flowers, etc., made of pith (Æschynomene aspera), and called pu karagam (flower pot).

The Pallis live in separate streets or quarters distinctively known as the Palli teru or Kudi teru (ryots’ quarter). The bulk of them are labourers, but many now farm their own lands, while others are engaged in trade or in Government service. The occupations of those whom I have examined at Madras and Chingleput were as follows:— • Merchant. • Cultivator. • Bullock and pony cart driver. • Printer. • Lascar. • Sweetmeat vendor. • Flower vendor. • Fitter. • Sawyer. • Oil-presser. • Gardener. • Polisher. • Bricklayer. • Mason. Some of the Chingleput Palli men were tattooed, like the Irulas, with a dot or vertical stripe on the forehead. Some Irulas, it may be noted en passant, call themselves Tēn (honey) Vanniyans, or Vana (forest) Pallis. Like many other castes, the Pallis have their own caste beggars, called Nōkkan, who receive presents at marriages and on other occasions. The time-honoured panchāyat system still prevails, and the caste has headmen, entitled Perithanakkāran or Nāttamaikkāran, who decide all social matters affecting the community, and must be present at the ceremonial distribution of pānsupāri.

The Kōvilars, and some others who aspire to a high social status, practice infant marriage, but adult marriage is the rule. At the betrothal ceremony, the future bridegroom goes to the house of his prospective father-in-law, where the headman of the future bride must be present. The bridegroom’s headman or father places on a tray betel, flowers, the bride-price (pariyam) in money or jewels, the milk money (mulapāl kūli), and a cocoanut. Milk money is the present given to the mother of the bride, in return for her having given nourishment to the girl during her infancy. All these things are handed by the bridegroom’s headman to the father or headman of the bride, saying “The money is yours. The girl is ours.” The bride’s father, receiving them, says “The money is mine. The girl is yours.” This performance is repeated thrice, and pān-supāri is distributed, the first recipient being the maternal uncle. The ceremony is in a way binding, and marriage, as a rule, follows close on the betrothal. If, in the interval, a girl’s intended husband dies, she may marry some one else. A girl may not marry without the consent of her maternal uncle, and, if he disapproves of a match, he has the right to carry her off even when the ceremony is in progress, and marry her to a man of his selection. It is stated, in the Vannikula Vilakkam, that at a marriage among the Pallis “the bride, after her betrothal, is asked to touch the bow and sword of the bridegroom. The latter adorns himself with all regal pomp, and, mounting a horse, goes in procession to the bride’s house where the marriage ceremony is celebrated.”

The marriage ceremony is, in ordinary cases, completed in one day, but the tendency is to spread it over three days, and introduce the standard Purānic form of ritual. On the day preceding the wedding-day, the bride is brought in procession to the house of the bridegroom, and the marriage pots are brought by a woman of the potter caste. On the wedding morning, the marriage dais is got ready, and the milk-post, pots, and lights are placed thereon. Bride and bridegroom go separately through the nalagu ceremony. They are seated on a plank, and five women smear them with oil by means of a culm of grass (Cynodon Dactylon), and afterwards with Phaseolus Mungo (green gram) paste. Water coloured with turmeric and chunām (ārathi) is then waved round them, to avert the evil eye, and they are conducted to the bathing-place.

While they are bathing, five small cakes are placed on various parts of the body—knees, shoulders, head, etc. When the bridegroom is about to leave the spot, cooked rice, contained in a sieve, is waved before him, and thrown away. The bridal couple are next taken three times round the dais, and they offer pongal (cooked rice) to the village and house gods and the ancestors, in five pots, in which the rice has been very carefully prepared, so as to avoid pollution of any kind, by a woman who has given birth to a first child. They then dress themselves in their wedding finery, and get ready for the tying of the tāli. Meanwhile, the milk-post, made of Odina Wodier, Erythrina indica, or the handle of a plough, has been set up. At its side are placed a grindstone, a large pot, and two lamps called kuda-vilakku (pot light) and alankara-vilakku (ornamental light).

The former consists of a lighted wick in an earthenware tray placed on a pot, and the latter of a wooden stand with several branches supporting a number of lamps. It is considered an unlucky omen if the pot light goes out before the conclusion of the ceremonial. It is stated by Mr. H. A. Stuart that in the North Arcot district “in the marriage ceremony of the Vanniyans or Pallis, the first of the posts supporting the booth must be cut from the vanni (Prosopis spicigera), a tree which they hold in much reverence because they believe that the five Pandava Princes, who were like themselves Kshatriyas, during the last year of their wanderings, deposited their arms in a tree of this species. On the tree the arms turned into snakes, and remained untouched till the owners’ return.” The Prosopis tree is worshipped in order to obtain pardon from sins, success over enemies, and the realisation of the devotee’s wishes.

When the bride and bridegroom come to the wedding booth dressed in their new clothes, the Brāhman purōhit gives them the threads (kankanam), which are to be tied round their wrists. The tāli is passed round to be blessed by those assembled, and handed to the bridegroom, who ties it on the bride’s neck. While he is so doing, his sister holds a light called Kamākshi vilakku. Kamākshi, the goddess at Conjeeveram, is a synonym for Siva’s consort Parvathi. The music of the flute is sometimes accompanied by the blowing of the conch shell while the tāli is being tied, and omens are taken from the sounds produced thereby. The tāli-tying ceremony concluded, the couple change their seats, and the ends of their clothes are tied together. Rice is thrown on their heads, and in front of them, and the near relations may tie gold or silver plates called pattam. The first to do this is the maternal uncle. Bride and bridegroom then go round the dais and milk-post, and, at the end of the second turn, the bridegroom lifts the bride’s left foot, and places it on the grindstone. At the end of the third turn, the brother-in-law, in like manner, places the bridegroom’s left foot on the stone, and puts on a toe-ring. For so doing, he receives a rupee and betel.

The contracting couple are then shown the pole-star (Arundhati), and milk and fruit are given to them. Towards evening, the wrist-threads are removed, and they proceed to a tank for a mock ploughing ceremony. The bridegroom carries a ploughshare, and the bride a small pot containing conji (rice gruel). A small patch of ground is turned up, and puddled so as to resemble a miniature field, wherein the bridegroom plants some grain seedlings. A miniature Pillayar (Ganēsa) is made with cow-dung, and betel offered to it. The bridegroom then sits down, feigning fatigue, and the bride gives him a handful of rice, which his brother-in-law tries to prevent him from eating. The newly-married couple remain for about a week at the bride’s house, and are then conducted to that of the bridegroom, the brother-in-law carrying a hundred or a hundred and ten cakes. Before they enter the house, coloured water and a cocoanut are waved in front of them, and, as soon as she puts foot within her new home, the bride must touch pots containing rice and salt with her right hand. A curious custom among the Pallis at Kumbakōnam is that the bride’s mother, and often all her relatives, are debarred from attending her marriage. The bride is also kept gōsha (in seclusion) for all the days of the wedding.

It is noted by Mr. Hemingway that some of the Pandamuttu Pallis of the Trichinopoly district “practice the betrothal of infant girls, the ceremony consisting of pouring cow-dung water into the mouth of the baby. They allow a girl to marry a boy younger than herself, and make the latter swallow a two-anna bit, to neutralise the disadvantages of such a match. Weddings are generally performed at the boy’s house, and the bride’s mother does not attend. The bride is concealed from view by a screen.”

It is said that, some years ago, a marriage took place at Panruti near Cuddalore on the old Svayamvara principle described in the story of Nala and Damayanti in the Mahābhārata. According to this custom, a girl selects a husband from a large number of competitors, who are assembled for the purpose. Widow remarriage is permitted. At the marriage of a widow, the tāli is tied by a married woman, the bridegroom standing by the side, usually inside the house. Widow marriage is known as naduvittu tāli, as the tāli-tying ceremony takes place within the house (naduvīdu).

To get rid of the pollution of the first menstrual period, holy water is sprinkled over the girl by a Brāhman, after she has bathed. She seats herself on a plank, and rice cakes (puttu), a pounding stone, and ārathi are waved in front of her. Sugar and betel are then distributed among those present.

The dead are sometimes burnt, and sometimes buried. As soon as an individual dies, the son goes three times round the corpse, carrying an iron measure (marakkal), wherein a lamp rests on unhusked rice. The corpse is washed, and the widow bathes in such a way that the water falls on it. Omission to perform this rite would entail disgrace, and there is an abusive phrase “May the water from the woman’s body not fall on that of the corpse.” The dead man and his widow exchange betel three times. The corpse is carried to the burning or burial-ground on a bamboo stretcher, and, on the way thither, is set down near a stone representing Arichandra, to whom food is offered. Arichandra was a king who became a slave of the Paraiyans, and is in charge of the burial-ground. By some Pallis a two-anna piece is placed on the forehead, and a pot of rice on the breast of the corpse. These are taken away by the officiating barber and Paraiyan respectively. Men who die before they are married have to go through a post-mortem mock marriage ceremony. A garland of arka (Calotropis gigantea) flowers is placed round the neck of the corpse, and mud from a gutter is shaped into cakes, which, like the cakes at a real marriage, are placed on various parts of the body.

A curious death ceremony is said by Mr. Hemingway to be observed by the Arasu Pallis in the Trichinopoly district. On the day after the funeral, two pots of water are placed near the spot where the corpse was cremated. If a cow drinks of the water, they think it is the soul of the dead come to quench its thirst. In some places, Palli women live in strict seclusion (Gōsha). This is particularly the case in the old Palaigar families of Ariyalūr, Udaiyarpālaiyam, Pichavaram, and Sivagiri.

The caste has a well-organised Sangham (association) called Chennai Vannikula Kshatriya Mahā Sangham, which was established in 1888 by leaders of the caste. Besides creating a strong esprit de corps among members of the caste in various parts of the Madras Presidency, it has been instrumental in the opening of seven schools, of which three are in Madras, and the others at Conjeeveram, Madhurantakam, Tirukalikundram and Kumalam. It has also established chuttrams (rest-houses) at five places of pilgrimage. Chengalvarāya Nāyakar’s Technical School, attached to Pachaiappa’s College in Madras, was founded in 1865 by a member of the Palli caste, who bequeathed a large legacy for its maintenance. There is also an orphanage named after him in Madras, for Palli boys. Gōvindappa Nāyakar’s School, which forms the lower secondary branch of Pachaiappa’s College, is another institution which owes its existence to the munificence of a member of the Palli caste. The latest venture of the Pallis is the publication of a newspaper called Agnikuladittan (the sun of the Agnikula), which was started in 1908.

Concerning the Pallis, Pallilu, or Palles, who are settled in the Telugu country as fishermen, carpenters, and agriculturists, Mr. H. A. Stuart writes that “it seems probable that they are a branch of the great Palli or Vanniya tribe, for Buchanan refers to the Mīna (fish) Pallis and Vana Pallis.” As sub-castes of these Pallis, Vada (boatmen), Marakkādu and Ēdakula are given in the Census Report, 1901. In the North Arcot Manual, Palli is given as a sub-division of the Telugu Kāpus. In some places the Pallis call themselves Palle Kāpulu, and give as their gōtram Jambumāharishi, which is a gōtram of the Pallis. Though they do not intermarry, the Palle Kāpulu may interdine with the Kāpus. Concerning the caste-beggars of the Pallis, and their legendary history, I read the following account. I came upon a noisy procession entering one of the main streets of a town not far from Madras. It was headed by spearmen, swordsmen, and banner-bearers, the last carrying huge flags (palempores) with representations of lions, tigers, monkeys, Brahmany kites, goblins and dwarfs. The centre of attraction consisted of some half dozen men and women in all the bravery of painted faces and gay clothing, and armed with swords, lances, and daggers.

Tom-toms, trumpets, cymbals, and horns furnished the usual concomitant of ear-piercing music, while the painted men and women moved, in time with it, their hands and feet, which were encircled by rows of tiny bells. A motley following of the tag-rag and bob-tail of the population, which had been allured thither by the noise and clamour, brought up the rear of the procession, which stopped at each crossing. At each halt, the trumpeters blew a great and sonorous blast, while one of the central figures, with a conspicuous abdominal development, stepped forward, and, in a stentorian voice, proclaimed the brave deeds performed by them in the days gone by, and challenged all comers to try conclusions with them, or own themselves beaten. I was told that the chief personages in the show were Jātipillays (literally, children of the caste), who had arrived in the town in the course of their annual tour of the country, for collecting their perquisites from all members of the Palli or Padiāchi caste, and that this was how they announced their arrival.

The perquisite levied is known as the talaikattu vari (poll-tax, or literally the turban tax), a significant expression when it is borne in mind that only the adult male members of the caste (those who are entitled to tie a cloth round their heads) are liable to pay it, and not the women and children. It amounts to but one anna per head, and is easily collected. The Jātipillays also claim occult powers, and undertake to exhibit their skill in magic by the exorcism of devils, witchcraft and sorcery, and the removal of spells, however potent. This operation is called modi edukkirathu, or the breaking of spells, and sometimes the challenge is taken up by a rival magician of a different caste. A wager is fixed, and won or lost according to the superior skill of the challenger or challenged. Entering into friendly chat with one of the leading members of the class, I gleaned the following legend of its origin, and of the homage accorded to it by the Pallis. In remote times, when Salivahana was king of the Chōla country, with its capital at Conjeeveram, all the principal castes of South India had their head-quarters at the seat of government, where each, after its own way, did homage to the triple deities of the place, namely, Kamakshi Amman, Ekambrasvarar, and Sri Varadarājaswāmi.

Each caste got up an annual car festival to these deities. On one of these occasions, owing to a difference which had arisen between the Seniyans (weavers), who form a considerable portion of the population of Conjeeveram, on one side, and the Pallis or Vanniyans on the other, some members of the former caste, who were adepts in magic, through sheer malevolence worked spells upon the cars of the Pallis, whose progress through the streets first became slow and tedious, and was finally completely arrested, the whole lot of them having come to a stand-still, and remaining rooted on the spot in one of the much frequented thoroughfares of the city. The Pallis put on more men to draw the cars, and even employed elephants and horses to haul them, but all to no purpose. As if even this was not sufficient to satisfy their malignity, the unscrupulous Seniyars actually went to King Salivahana, and bitterly complained against the Pallis of having caused a public nuisance by leaving their cars in a common highway to the detriment of the public traffic.

The king summoned the Pallis, and called them to account, but they pleaded that it was through no fault of theirs that the cars had stuck in a thoroughfare, that they had not been negligent, but had essayed all possible methods of hauling them to their destination by adding to the number of men employed in pulling them, and by having further tried to accelerate their progress with the aid of elephants, camels, and horses, but all in vain. They further declared their conviction that the Seniyars had played them an ill-turn, and placed the cars under a spell. King Salivahana, however, turned a deaf ear to these representations, and decreed that it was open to the Pallis to counteract the spells of their adversaries, and he prescribed a period within which this was to be effected. He also tacked on a threat that, in default of compliance with his mandate, the Pallis must leave his kingdom for good and ever.

The Pallis sought refuge and protection of the goddess Kamakshi Amman, whose pity was touched by their sad plight, and who came to their aid. She appeared to one of the elders of the caste in a dream, and revealed to him that there was a staunch devotee of hers—a member of their caste—who alone could remove the spells wrought by the Seniyars, and that this man, Ramasawmy Naikan, was Prime Minister in the service of the Kodagu (Coorg) Rāja. The desperate plight they were in induced the Pallis to send a powerful deputation to the Rāja, and to beg of him to lend them the services of Ramasawmy Naik, in order to save them from the catastrophe which was imminent. The Rāja was kind enough to comply.

The Naik arrived, and, by virtue of his clairvoyant powers, took in the situation at a glance. He found myriads of imps and uncanny beings around each of the car-wheels, who gripped them as by a vice, and pulled them back with their sinewy legs and hands every time an attempt was made to drag them forwards. Ramasawmy Naik by no means liked the look of things, for he found that he had all his work cut out for him to keep these little devils from doing him bodily harm, let alone any attempt to cast them off by spells. He saw that more than common powers were needed to face the situation, and prayed to Kamakshi Amman to disclose a way of overcoming the enemy. After long fasting and prayers, he slept a night in the temple of Kamakshi Amman, in the hope that a revelation might come to him in his slumber. While he slept, Kamakshi Amman appeared, and declared to him that the only way of overcoming the foe was for the Pallis to render a propitiatory sacrifice, but of a most revolting kind, namely, to offer up as a victim a woman pregnant with her first child. The Pallis trembled at the enormity of the demand, and declared that they would sooner submit to Salivahana’s decree of perpetual exile than offer such a horrible sacrifice.

Ramasawmy Naik, however, rose to the occasion, and resolved to sacrifice his own girl-wife, who was then pregnant with her first child. He succeeded in propitiating the deity by offering this heroic sacrifice, and the spells of the Seniyars instantly collapsed, and the whole legion of imps and devils, who had impeded the progress of the Pallis’ car, vanished into thin air. The coast having thus been cleared of hostile influences, Ramasawmy Naik, with no more help than his own occult powers gave him, succeeded in hauling the whole lot of cars to their destination, and in a single trip, by means of a rope passed through a hole in his nose.

The Pallis, whose gratitude knew no bounds, called down benedictions on his head, and, falling prostrate before him, begged him to name his reward for the priceless service rendered by him to their community. Ramasawmy Naik only asked that the memory of his services to the caste might be perpetuated by the bestowal upon him and his descendants of the title Jāti-pillay, or children of the caste, and of the privilege of receiving alms at the hands of the Pallis; and that they might henceforth be allowed the honour of carrying the badges of the caste—banners, state umbrellas, trumpets, and other paraphernalia—in proof of the signal victory they had gained over the Seniyars.”