Rapes in India: the legal position after 2013

This is a collection of newspaper articles selected for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Changes in the law after February 3, 2013

From ‘Allegation raj’ that burns at stake

Principle of law? Ha-ha

R. BALAJI, IMRAN AHMED SIDDIQUI AND CHARU SUDAN KASTURI

The changing times have fuelled concerns.

The laws that were changed after the December 16, 2012 brutality in Delhi and the backlash that dramatically transformed public discourse may have pushed the country into a tightrope walk between surer justice for the sufferers and a lynchmob presumption that the accused are guilty.

The gist of their views suggests that the cornerstone of law — every suspect is presumed innocent until proven guilty — must be kept in mind always while commenting on such sensitive cases. Besides, police investigation must be allowed to proceed in an environment free of shrill rhetoric on which an “allegation raj” feeds and fattens itself.

Law changes

Tarun Tejpal case

Tarun Tejpal, the Tehelka founder accused of raping a junior during a Goa literary conclave in November 2013, would have been booked for the much weaker charge of sexual harassment under the earlier laws.

Tejpal would have faced the prospect of a maximum of two years in jail and a fine under the earlier laws that described any sexual crime short of rape with the Macaulay-era wording “outraging the modesty of women” and prescribed a uniform punishment.

Under the new law, if convicted, he now faces anything between seven years and life in jail.

Justice Asok Kumar Ganguly case

The new laws will not apply to the charges against Justice Asok Kumar Ganguly because the alleged “unwelcome behaviour of a sexual nature” in December 2012 preceded the legal amendments carried out on February 3, 2013.

Going by the information made public so far, Ganguly, unlike Tejpal, would not have faced the charge of rape even under the new laws. But the punishment for the charges the former judge could face would have been different had the new laws applied, ranging from a year to seven years in prison.

Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act

Subjective terms

Added to this mix of criminal laws is the Sexual Harassment of Women at the Workplace Act that makes it mandatory for offices to set up a grievance redress mechanism to internally evaluate allegations of misconduct followed by a criminal complaint if the charges are found to be sound.

The cocktail of laws, however, is silent on the specifics of what can be viewed as humiliation, interference with work, creating an environment of intimidation and implied and explicit threats — the factors that define sexual harassment at the workplace.

It is equally unclear what constitutes “making sexually coloured remarks” or “unwelcome verbal conduct of a sexual nature” that the new criminal amendment law punishes with a year in jail.

But the rape laws describe in detail what constitutes the offence (see chart: ' The 2013 law vs the earlier position'). The definition of rape has been widened to such an extent that finding evidence to prove some charges would be difficult. In effect, although many feel that the law has been tightened, the task of prosecution may become all the more difficult to establish a charge in court in the absence of material evidence.

The law has yet to be tested in court conclusively but if cases under the new definition of rape are not eventually proved, future complainants may turn reluctant in approaching the police.

Witch-hunt frenzy

However, such questions have been blown away by the blizzard of opinions from those with little respect for the nuances of law that usually follow a complaint.

Senior lawyer K.T.S. Tulsi, who appeared on behalf of Tejpal at Delhi High Court, felt that a witch-hunt of those charged with sexual crimes was leading to premature presumption of guilt by society at large.

“The moment an allegation of sexual crime is made, people presume it to be true and start clamouring for the prosecution of the accused,” Tulsi said. “This is nothing but travesty of justice. Such is the frenzy that people believe in prosecution without following the procedure of law.”

Safeguards

The law does carry safeguards against misuse that in the absence of a public witch-hunt can ensure a fair trial, lawyers said.

Even before the new rape and sexual harassment laws came into being, the victim did not need to personally complain for the police to file an FIR — they could do so themselves. But the police need prima facie evidence to arrest the accused and to seek custody.

The new laws continue to allow the accused to challenge the complainant’s account in court, or during the police probe, senior lawyer Kamini Jaiswal said. “He can challenge the version given by the victim with facts,” she said.

The law continues to retain provisions that allow the accused, if acquitted, to seek damages in court from the complainant and the police for the time he spent in jail or the hurt to his reputation, although there is no provision for safeguarding the identity of the accused as in the case of the accuser.

“He can file a case of malicious prosecution against the complainant and the prosecuting agency and claim damages,” Jaiswal said.

But others have pointed out that such cases take time to conclude and reputations once destroyed are difficult to be restored with a stroke of a pen.

Accuser’s proof

Although the law does not bar complaints made even years after the alleged incident, it does put in place mechanisms to guard against false allegations.

The accuser has to provide details of the incident — the date, the time, place where she was harassed and any witnesses who may have come across the victim in a perturbed state soon after the incident — to substantiate her complaint, Jaiswal said.

The accused can challenge her version by producing alibi to suggest he was elsewhere at the time of the alleged crime.

But if both were present at the same place at the time mentioned — as in the cases of Tejpal as well as Ganguly — their personal accounts and that of witnesses will play a crucial role. Besides, the onus of proving the charges still lies on the prosecution.

The complainant’s version against Tejpal has been backed by three colleagues whom the young journalist had met immediately after the alleged assault. The intern had filed affidavits of three witnesses during her deposition against Ganguly.

A five-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court earlier in 2013 also held that if the complaint is filed late, the investigating officer should conduct a preliminary enquiry and be satisfied with its outcome before registering an FIR.

The 2013 law vs the earlier position

WHAT HAS CHANGED

Sexual harassment

OLD LAW

Section 354, the Indian Penal Code

Definition

• Reference limited to “assault or criminal force on a woman with the intent to outrage her modesty”

• Stalking, verbal abuse with sexual innuendoes, molestation and penile penetration of a woman’s body other than vagina were covered under this law as equivalent crimes

Punishment

Up to two years in jail or/and fine

New LAW

Amended Section 354

Category I

Seeks to explain what constitutes sexual harassment and defines differential punishment

• Physical contact and advances involving explicit sexual overtures

• Demand or request for sexual favours

• Sexually coloured remarks l Forcibly showing pornography

• Any other unwelcome physical, verbal or non-verbal conduct of sexual nature

Punishment

Up to one year in jail and/or fine

Category II

• Act with intent to disrobe a woman

• Watching or capturing a woman in a private act (bathing, naked, semi-naked or in a sexual act); capturing includes recording

Punishment

Between 3 and 7 years in jail and fine

Category III

• Stalking

Punishment

Between 1 and 3 years and/or fine

RAPE

• Section 375, the Indian Penal Code, deals with rape. The old law defined forcible sexual intercourse as rape

• The amended Section 375 defines rape as insertion of any object or body part by a man into any part of the body of a woman. Oral sex also constitutes rape. Forcing a woman to submit herself to the same by another man constitutes rape

• In the amended law, manipulating any body part of a woman that leads to rape as mentioned above will also be treated as rape. This holds gang rape participants accountable if they hold or bind the victim while someone else rapes her

• No change in the definition of forcible. It means against a woman’s will or consent; if the man isn’t her husband but she believes he is; she is intoxicated or drugged and in a state where she is unable to understand the nature and consequences of that to which she gives consent; or she is under 16

Old punishment

7 years to life imprisonment. But state governments frequently freed life convicts after 14 years

New punishment

7 years to life imprisonment. If the victim is reduced to a vegetative state or is seriously disfigured in addition to the rape, the maximum punishment can extend to the “remainder of that person’s natural life”

2014: The effect of “police reforms“

Sex offence cases up after reforms

Somreet Bhattacharya The Times of India Dec 16 2014

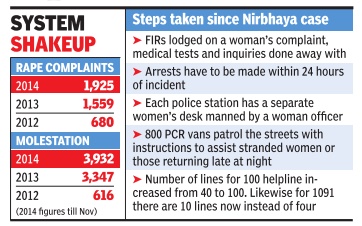

The “police reforms“ that followed the Nirbhaya case led to a free and easy registration of crimes against women. As a result, now the police have to note down a woman's complaint verbatim. Earlier, the police used to modify the complaints. The new system has also done away with medical tests and inquiries prior to the registration of the case.

Police officers admit that this has increased the number of rape cases registered by nearly 150% of what it used to be. At the same time, it has also led to a lot of frivolous rape cases being filed to settle personal scores as well.

Officers say that the free registration has increased the number of FIRs getting registered per year from 680 in 2012 to 1,559 cases in 2013 and 1,925 cases till November this year. The number of molestation cases has also gone up from 615 in 2012 to 3,347 last year and 3,932 cases till November 2014.

According to a police officer, once a woman registers a complaint, the police have to treat it as a statement and arrest the accused within a week. Even activists agree that now women don't have to run from pillar to post to register an FIR. “Once a case is registered, the general perception of the public, including the family members of the victim, tends to question the character of the woman. People start judging the woman first and then the accused,“ said Manisha Goel, an MBA aspirant and an activist.

The police also admit that the increase in the number of cases has resulted in the piling up of cases at each police station, affecting the investigations. Now, in a rape case, the investigating officer has to submit a chargesheet within 20 days of it being registered, which forces them to complete the probe in a hurry . The problem is compounded by the shortage of women staff at police stations as well, police officers claim.

Pending rape cases

Over 31,000 rape cases pending in High Courts

December 17 2014

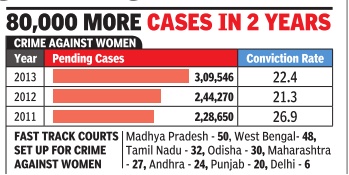

Crimes against women are on the rise, and so is the pendency of such cases in the subordinate and high courts across the country. In the last three years, number of cases relating to sexual harassment, kidnapping and abduction including rape has gone up from 2.28 lakh to 3.09 lakh. Over 31,000 rape cases are pending in high courts alone.

Concerned at increasing pendency of cases of crime against women and children, the law ministry has written to the state governments and the chief justices of HCs to constitute fast track courts for speedy trial of such cases. The conviction rate in these cases, however, came down from 27% to 22% between 2011 and 2013.

After the December 2012 Delhi rape case, the government had asked the state gov ernments to allocateTOTAL (ALL S additional funds for setting up of fast track courts (FTCs) for trials related to crime against women and children.

This has resulted in at least 318 FTCs being set up by various HCs, designating them exclusively for trials of cases related to crime against women. Madhya Pradesh has set up highest FTCs for women and children (50), followed by West Bengal (48).

There are 310 cases of sexual harassment pending in the Supreme Court while it has L STATES) 318 disposed of 1,455 since 2009. In the HCs, the pendency of rape r cases is as high as 31,386 while e 15,453 have been disposed of in the last three years.

See also

Age of consent Crimes against women: India Juveniles, benefits and privileges of Juvenile delinquency in India Especially the section 'Rape by juveniles' Premarital sex

Rapes in India Rapes in India: court verdicts Rapes in India: the legal position after 2013

<>Rapes in India: Compensation and help for survivors