Kalpana Saroj

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. |

Contents |

Kalpana Saroj is...

Anahita Mukherji The Times of India Feb 08 2015, Dalit honcho scripts `historic' buy

Kalpana Saroj is chairperson of Kamani Tubes and winner of a Padma Shri award in 2013.

Kalpana Saroj was born, a couple of years after Dr Ambedkar's death, to a poor Dalit family in rural Vidarbha. Married off at the age of 12 to a man many years older, she was tormented by her in-laws and her marriage fell apart before she turned 13. After a failed suicide bid, she was determined to make something of her life and chose to script her success in Mumbai.

When she first arrived in the city, she worked as a seamstress for Rs 2 a day . She then took a loan, turned entrepreneur and finally worked her way up the ladder. Nearly a decade ago, she took control of Kamani Tubes when the company was sick and turned it around.

Reviving Kamani Tubes

How dalit entrepreneur Kalpana Saroj revived Kamani Tubes Ltd

Naren Karunakaran, ET Bureau Jul 29, 2011 Economic Times

KTL is handed over to workers

Ramjibhai Kamani once rubbed shoulders with Gandhiji and later Pandit Nehru, paving the road for an industrial India, along with the Tatas, Birlas, and the Bajajs. He even stepped out of business for a while, taking to spinning khadi in rural Gujarat.

The fact that, in June 2011, the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) released, Kamani Tubes Ltd (KTL), a company of his group and comatose for decades, to chart an independent course. Ramjibhai’s son Navinbhai Kamani was the chairman of KTL at the time. Navinbhai handed over his embattled company to workers in 1988, after a prolonged spell of labour trouble.

A Supreme Court-directed move, it was then hailed as a bold experiment in worker ownership and management. Unfortunately, KTL, which made non-ferrous metal tubes and pipes, hit the rocks within a decade, with the company retiring sick in 1995.

Kalpana Saroj, who bought the company and nursed it back to health in a daring revival scheme, starting 2006, is a dalit.

Saroj visited Navinbhai many years later to write out a cheque for Rs 51 lakh — his dues, including provident fund, as part of the KTL restructuring exercise. "Navinbhai's financial condition was precarious; and I presume the money did him some good," says Saroj, sitting in her well-appointed office, once the boardroom of the Kamani group, at Kamani Chambers, in Mumbai's Ballard Estate.

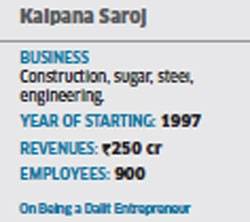

Kalpana Saroj’s journey—and empire

Kalpana Saroj of Kalpana Saroj & Associates (KSA) has traversed quite a distance from Murtizapura, a hamlet in the interiors of Maharashtra.

Today, she presides over varied businesses. The single factory Sai Krupa Sakhar Karkhana in Ahmednagar, in which she holds a substantial stake, is graduating to an integrated sugar complex.

Capacity has been enhanced to 7,500 TCD (tonnes of sugarcane crushed per day), and a 60 KLD (kilo litres per day) distillery is coming up. "We are also building a 35 MW co-generation power plant," she says.

A diversification into steel manufacturing and mining has come about recently. Initial investments of Rs 10 crore for a 100 tonnes per day steel plant has been made at Wada, on the outskirts of Mumbai. A bauxite mining initiative across 1,230 acres in Udgir, along the Maharashtra-Karnataka border, is being drawn out.

Meanwhile, she has also resurrected the Kamani brand in the Gulf through Al Kamani in Kuwait and Kalpana Saroj LLC in Dubai to cater to the huge demand for copper tubes, especially from the water and sanitation sector. "The Arabs are familiar with the brand," recalls Navinbhai. "They would, in my time, often pay a premium for our products."

Into the storm...

Daughter of a police constable, Saroj has had a troubled past. She was married off at 12, and migrated to Mumbai's slums. A broken marriage forced her to return to her village. She couldn't fit in, and therefore, attempted suicide, and survived.

Determined to chart her own destiny, she returned to Mumbai and laboured for Rs 2 a day at a hosiery unit, married again, took over a steel almirah fabrication business on her husband's death, and stumbled into the construction business. From then on, she rode the realty wave.

Alongside, Saroj dabbled in social work, which brought her into close proximity with politicians of all hues. It enabled her to climb the social ladder quickly. Her critics view this as an opportunistic trait, but it's also true that business easily cultivates friends and patrons in high places.

The revival

"My capital has always been people," explains Saroj. Her tryst with KTL was also thrown up by the ecosystem she was in. The company was weighed down by a debt of Rs 116 crore, salary and provident fund dues of over 500 workers, and over 170 court cases. "Takeover suitors would appear, conduct a due diligence and flee for dear life," recalls Ramesh Bondkar, general secretary of Kamani Kamgar Ekta, KTL's workers union.

However, Saroj bid for the company when it was put up for sale by IDBI, the operating agency of the BIFR. In March 2006, her scheme for revival was accepted. She settled all claims by lenders. Workers dues of over Rs 8.5 crore were cleared. "I paid Rs 90 lakh more than what was due to workers as a gesture of goodwill," explains Saroj.

...And through it

The revival, though, wasn't easy. She has had to confront the old Kamani Employees Union (KEU), which accuses Saroj of coming in merely to strip KTL. D Thankappan, now with Delhi's New Trade Union Initiative (NTUI), who earlier piloted the experiment in workers management, has always maintained that Saroj is an interloper, with political contacts; and that, as a builder, she is eying the company's assets. Her counter: except for a 3.75 acre piece of land in Bangalore, the company has no property whatsoever. Even the land on which Kamani Chambers stands is on leasehold land of the Port Trust.

"KEU wants liquidation of the company, and not revival of the company and restoration of workers livelihoods," laments MK Gore, MD, KTL. "It's inexplicable." Even the Bombay High Court, in an order of October 2009, frowned upon the predatory petition-filing antics of the KEU and opined: "...the whole purpose of filing the petition appears to be to create hindrance in the implementation of the scheme..."

Govind Kharatmol and Ramchandra Kadam, workers who survived by driving rickshaws all these years, accuse a ruling KEU clique for ending a wonderful workers initiative by systematically siphoning out money. "They tasted blood then, and now, they want more," says Kharatmol. Saroj maintains this too shall pass. Only two of the KEU affiliated workers now remain on her rolls, and they retire by the year-end. KTL started commercial production in December 2010.

Sales are inching up; it stands at about Rs 1 crore or so. Three new gas furnaces have been installed at KTL's new plant in Mumbai. The company is quickly moving into newer areas of demand. "We are developing cupro-nickel alloy tubes, required in large quantities by power plants," reveals Ashish Deshpande, CEO, KTL. Also on the drawing board are SBP brass wires for ball pen tips. It's powering along, slowly. Few companies in India has had such a chequered history, and fewer still have such a chairperson: a gutsy, at times reckless, dalit; a school drop-out; child-bride; slum dweller; suicide survivor

The house on King Henry Road

In July 2014, Saroj was in Paris to attend a conference organized by the Ambedkar International Mission, a global organization of Dalits around the world. “After the conference, a few of us headed to London. Whenever we're in the city , we make it a point to visit the house where Ambedkar once lived,“ says Saroj, who was accompanied on her visit by R K Gaikwad, Maharashtra's former commissioner for social welfare, and Gautam Chakravarthy of the Federation of Ambedkarites & Buddhist Organizations, UK, among others. “We [noticed that] the house was up for sale,” she says, adding that it cost Rs 40 crore, more than any Dalit organization could afford.

For the next six months, Saroj teamed up with prominent members of the Dalit community in India and the UK and lobbied with the Centre [Government of India ] and the [Maharashtra] state government to bid for the house.

The Maharashtra government agreed and succeeded in buying the house.