Kistna District , 1908

Contents |

Kistna District, 1908

Physical aspects

(Krishna). — district on the north-eastern coast of the Madras Presidency, lying between 15degree 37' and 17 degree 9' N. and 79 degree 14' and 81° 33' E., with an area of 8,498 square miles 1 . It is bounded on the east by the Bay of Bengal ; on the west by the Nizam's Dominions and Kurnool District; and on the north and south by the Districts of Godavari and Nellore respectively. It is named after the great river which flows along much of its western boundary, and then, turning sharply, runs right across it from north- west to south-east, and forms its most striking natural as oects feature. On the extreme west the District consists of stony uplands, dotted with rocky hills or crossed by low ranges ; the centre and north are a level plain of black cotton soil ; but the eastern portion is made up of the wide alluvial delta of the Kistna river, an almost flat expanse, covered with irrigated rice-fields, and containing some of the most fertile land in the Presidency. These three tracts form three sharply differentiated natural divisions. The coast is fringed with a wide belt of blown sand, sometimes extending inland for several miles. Along the shore the dunes rise to the height of from 30 to 50 feet. The only hills of any note are those in the west of the District. They are outliers of the great chain of the Eastern Ghats, and the Palnad taluk is almost surrounded by them. Besides the Kistna, there are no rivers, except a few fitful hill torrents and three or four minor tributaries of the great river. The Gundlakamma, which rises in Kurnool, traverses a corner of the Vinukonda taluk from west to east and then passes into Nellore. The Colair Lake (Kolleru) lies within the District.

The broad central belt of low-lying country, situated at the foot of the Eastern Ghats and sloping towards the sea, is covered by Archaean gneisses. These consist of a thinner-bedded schistose series (which

1 While this work was under preparation the area ol the District was changed, the taluks of Ellore, Yernagfidem, Tanuku, BhTmavaram, and Narasapur (excluding Nagaram Island) being added to it from Godavari District, and those of Tenali, Guntur, Sattanapalle, Palnad, Bapatla, Narasaraopet, and Vinukonda being formed (with the Ongole taluk of Nellore) into a new Guntur District. The present article refers to the District as it stood before these alterations. includes mica and chloride schists with quartzites), and of more massive granitoid gneisses, all much interbanded and disturbed. They are also pierced by occasional younger dioritic dikes, granite, felsite, and quartz veins. North-west of this Archaean belt comes the more elevated, often plateau-like, country of the Cuddapah and Kurnool series of the Purana group. This is an enormous series (aggregating over 20,000 feet thick) of unfossiliferous, but little altered, sedimentary strata, gently inclined as a whole. They comprise repetitions of quartzitic and shaly sub-series, with occasional conglomerates and limestones, and interbedded traps near the base. The Kurnools overlie the Cuddapahs unconformably, forming numerous plateaux, and possess a basal diamantiferous conglomerate. South-east of the Archaean band are a few scattered outliers of the much younger Upper Gond- wanas, with plant-beds and Jurassic marine shells, a double sandstone series with shales between ; and these in turn underlie a little sub- recent Cuddalore sandstone, and great stretches of coastal and deltaic alluvium with a few patches of lateritic rock.

The flora of the District presents no special characteristics, the plants being mainly the usual cultivation weeds of the Coromandel coast. Along the sandy shore are found the usual sand-binders, Spinifex squarrosus and Ipomoea ; and cashew-nut trees (Anacardium occidentale) occur in scattered nooks. The principal crops and forest trees are referred to later. Generally speaking, the District is very bare of tree-growth.

Wild animals are far from plentiful. Tigers and sambar are found in the Palnad and Vinukonda jungles, on the Medasala Durga ridge, and on the Kondapalli and Kondavid hills. Leopards and an occa- sional bear lurk in the rocky eminences of some of the inland taluks. A few antelope are to be seen in the Bapatla taluk, and wild hog are not uncommon in various parts. Bird life is more prominent. Almost every species of South Indian feathered game, except the woodcock and hill partridge, is to be found in the District. Snipe, duck, and teal abound in the season ; and the Colair Lake is the home of almost all the known inland aquatic birds. It is also fairly stocked with fish.

The climate of the District, although in parts trying owing to the great heat, may be set down as healthy. Fever is on the whole uncommon. Masulipatam (the head-quarters), with a mean tempera- ture of 82", a recorded maximum of 117 , and a minimum of 58 , jses perhaps the most equable climate; and on the coast gener- ally, except for a short time in the month of May, the heat is never unbearable. The temperature of the Palnad, Sattanapalle, Nandigama, and Tiruvur taluks during November, December, and January resembles that of the Mysore plateau, the thermometer falling to 65 ; but the temperature becomes extremely high during May and June. Of the rainfall, nearly two-thirds is usually registered during the south-west monsoon, the first showers of which begin to fall in May. The remainder of the supply is received in the three last months of the year, but the fall in October and November is as a rule much more irregular than in the earlier months. It is at times exceedingly heavy, owing to the cyclones that often visit the coast. The annual rainfall for the District as a whole during the thirty years from 1870 to 1899 averaged 2>Z inches. But this is not evenly distributed ; as elsewhere along this coast, the fall in the coast tracts, such as Masulipatam, Tenali, and Bapatla, is considerably heavier than that in the inland taluks of Palnad, Sattanapalle, and Narasaraopet. Scarcity has been known in one or two bad years, but the pinch of real famine has not been felt since the Kistna irrigation system was completed. Floods, however, are frequent. In 1874, 1875, 1S82, 1895, 1896, and 1903 they did damage which was sometimes very great. All of them were due to the Kistna overflowing its banks. The highest flood on record in the river was in 1903, when the water breached the bank of the main canal and submerged much of the delta. Masulipatam, the District head-quarters, has twice been visited by disastrous tidal waves. In 1779 the sea flowed 12 feet deep through the Dutch factory, a great part of the town was washed away, and at least 20,000 persons were drowned and lay unburied in the streets. In 1864 an even worse wave inundated the place. The sea penetrated 17 miles inland, sub- merging 780 square miles and drowning as many as 30,000 people.

History

The earliest known rulers of the District were the Buddhist dynasty of the Andhras, who built the stupa at Amaravati and whose curious leaden coins are still occasionally found. Following them came, about the beginning of the seventh century a. d., the Brahmanical Eastern Chalukyas, the excavators of the cave temple at Undavalle and other rock-cut shrines. About 999 they in their turn were supplanted by the Cholas. The latter some two centuries later gave place to the Ganpatis of Warangal, during whose rule Marco Polo landed in the District at Motupalle, now an obscure fishing village in the Bapatla taluk. The District then came under a dual sway, the kings of Orissa ruling the northern part, while the south fell into the hands of a line of cultivators who rose to considerable power and are known to history as the Reddi kings. The ruins of their fortresses at Kondavid, Bellamkonda, and Kondapalli are still to be seen. In 15 15 king Krishna Deva of Vijayanagar wrested the north of the District from the Gajapati kings of Orissa ; and it passed, on the fall of the Vijayanagar empire in 1565, to the Kutb Shahi line of Golconda, and was eventually absorbed (on the destruction of that dynasty in 1687) in the empire of Aurangzeb.

In 161 1 the English founded their second settlement in India at Masulipatam, which continued to be their head-quarters until these were finally removed to Madras in 1641. Three years after the found- ing of the English settlement came the Dutch, and in 1669 the French followed. It was not, however, till the year 1750 that any of the European powers exerted any political influence in the District. Two years after that date the Subahdar of the Deccan granted the whole of the Northern Circars to the French, and it was from them that this tract finally passed to the English. On the outbreak of hostilities in 1758, Colonel Forde, who was sent by Clive from Bengal to attack the French in the Northern Circars, defeated them at Condore in Godavari District, and following them to Masulipatam besieged them there. Faced by a strong garrison in front and hemmed in behind by the Subahdar of the Deccan, the ally of the French, his ranks rapidly thinning with disease, Forde, as a counsel of despair, at length made an almost desperate night attack upon the Masulipatam fort and captured it. As a consequence of this victory, first the divisions of Masulipatam, Nizampatam, and part of Kondavld, and later the whole of the Circars, passed, by a grant from the Subahdar of the Deccan (confirmed by the emperor Shah Alam in 1765), to the Company. With the cession of the Palnad in 1801 by the Nawab of Arcot, the entire District finally became British territory. At first it was administered by a Chief and Council at Masulipatam, but in 1794 Collectors directly responsible to the Board of Revenue were appointed at Guntur and Masulipatam. In 1859 these two Collec- torates (except two taluks of the latter) were amalgamated into one District.

The most interesting archaeological remains in the District are its Buddhist antiquities, and the chief of these is the great stupa at Ama- ravati in the Sattanapalle taluk. This was discovered in 1796, and a portion of the sculptured marble rails of the processional circle was sent by Sir Walter Elliot to England, where it now lines one of the staircase walls in the British Museum. The Government Museums at Madras and Calcutta contain other pieces of the work. From inscriptions it is evident that the temple of Amareswara in the same village was origin- ally a Buddhist or Jain sanctuary, and in the neighbourhood are several mounds which may perhaps contain other relics of these faiths. In the Tenali taluk are the ruins of Chandavolu, a place of great antiquity containing a temple and Buddhist mound; and Buddhist stufias exist at JAGGAYYAPETA and GUDIVADA. Gold coins have been found at Chandavolu, and in 1874 some workmen came upon several masses of molten gold as large as bricks. There was formerly a fine Buddhist stupa at Bhattiprolu. Here a curious relic, consisting of a piece of bone (supposed to have been one of Buddha's bones) enclosed in a crystal casket lodged in a soapstone outer case, was found a few years ago. In the Vinukonda taluk stone circles (dolmens) abound and inscriptions are numerous.

Population

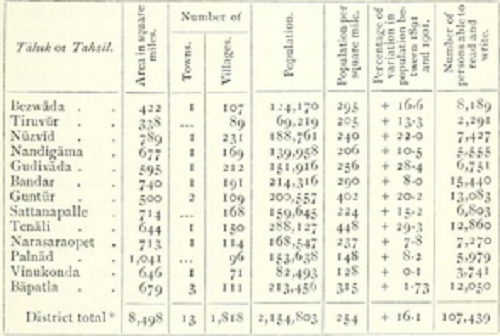

Kistna comprises the thirteen taluks and tahsils of which statistical particulars are given below : —

The area of the new Kistna District is 5,899 square miles, and its population 1,744,1 The head-quarters of the Bandar taluk are at Masulipatam, of Nuzvid at Gannavaram, and of Palnad at Guruzala. Those of the other ten taluks are at the places from which they are named. The population of the District in 1871 was 1,452,374; in 1881, 1,548,480; in 1891, 1,855,582 ; and in 1901, 2,154,803. During the last thirty years it has increased by 48 per cent., which, excluding the exceptional case of the Nilgiris, is the highest rate for any District in the Presidency ; and in the decade ending 1901 its growth was at the rate of 16 per cent., which was more rapid than in any other District. Of the nine taluks in the Presidency which showed the highest rates of increase in that period, four — namely, Tenali, Gudivada, Nuzvid, and Guntur — are in Kistna. Some of this growth is due to immigration, chiefly from Nellore and Vizagapatam. It is most conspicuous in the delta ; but even there, except in Tenali, the density of the population is still much less than in the neighbouring delta of the Godavari, and the rates of increase will probably continue to be high in future. The chief towns are the municipalities of Masulipatam, Bezwada, and Guntur, while Chirala and Tenali are the two most populous Unions. Of the total population, 1,912,914, or 89 per cent., are Hindus; 132,053, or 6 per cent., Musalmans ; and 101,414, or 5 per cent., Christians. The number of these last almost trebled during the twenty years ending 1901, and between 1891 and 1901 advanced by nearly 33,000, a larger increase than in any other District. In 1901 Christians formed a higher proportion of the population than in any other District north of Madras City.

Five per cent, of the people speak Hindustani. Telugu is the vernacular of practically all the rest, and is the prevailing language in every taluk. A peculiarity of the population is that it comprises fewer females than males, there being 976 of the former to every 1,000 of the latter. This characteristic occurs also in six other Districts which form, with Kistna, a fairly compact block of country in the centre of the Presidency. Of the Hindus, 97 per cent, belong to Telugu castes. The Kammas (311,000) and Telagas (cultivators, 148,000) are in greater strength than in any other District ; as also are the Madigas (leather-workers, 142,000), the Telugu Brahmans (106,000), and the Komatis (traders, 81,000). Brahmans of all classes number nearly 6 per cent, of the total Hindu and Animist population, which is an unusually high proportion. Among other castes which are commoner in Kistna than elsewhere may be mentioned the Bogams (dancing-girls), and the three beggar communities of the Bandas, Budubudukalas, and Vipravi- nodis. The latter beg only from Brahmans, and will only do their juggling tricks, for which they are famous, if a Brahman be present. Of the Musalmans, an overwhelmning majority returned themselves as Shaikhs, but Pathans and Saiyids are fairly plentiful, while Mughals are more than twice as numerous as in any other District.

The occupations of the people differ singularly little from the normal. Agriculture, as usual, enormously preponderates. At the Census of 1901 there were 101,414 Christians in Kistna District, of whom 100,841 were natives. The most numerous sect is that of the Baptists (39,027). The Lutheran and allied denominations number 34,877 ; while the Roman Catholic and Anglican communions are fairly equal in strength, possessing 14,511 and 11,157 members respectively.

The pioneers of Christianity in the District belonged to the Roman Catholic Church, being Jesuits who came out to India after the found- ing of the well-known mission at Madura. Little is now on record regarding their operations, but it is clear that their efforts were less continuous and strenuous than in Districts farther south. The suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1773 almost entirely checked their enterprise, and for many years few priests were left in the District, and some of the converts went back to Hinduism. In 1874 matters revived, four priests coming out from Mill Hill; and since then more has been done.

The Protestant missions are of much more recent origin. The best known of their missionaries, the Rev. Robert Noble, came to Masuli- patam in 1841 under the auspices of the Church Missionary Society, and worked there without intermission for twenty years, founding the college at Masulipatam which bears his name. The American Lutheran Mission was started at Guntur in 1842. Its converts are chiefly from the lower castes, and it works at Guntur and Narasaraopet. The Bap- tists began operations in 1866, but their converts outnumber those of any other denomination.

Agriculture

As has been mentioned, the District consists of three dissimilar areas : namely, the Palnad and the neighbouring tracts, where much of the soil is formed of detritus from the hills • the wide plain of the rest of the uplands, where it is black cotton soil ; and the delta, which is for the most part alluvial. Agri- cultural practice naturally differs according to the soil, the lighter land requiring only slight showers, the cotton country needing a thorough soaking, and the delta having to wait until the floods come down the river. There are three general classes of crop, corresponding more or less to the seasons : namely, the punasa, or early crop, sown just after the first burst of the monsoon in May or June ; the pedda, or big crop, between July and September ; and the pedda, or late crop, put down in November. The sowing of the ' wet ' land is principally done from July to October, by the middle of which month more than four-fifths of it should have been completed.

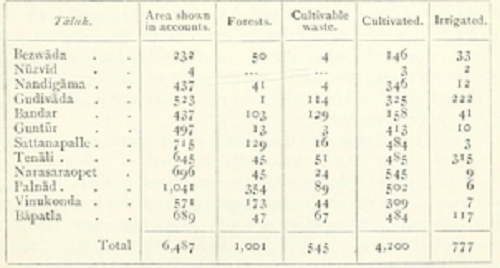

As much as one-fourth of the District consists of zamindari and inam lands. For the former of these no detailed particulars are on record. The area for which accounts are kept is 6,487 square miles, details of which, for 1903-4, are appended : —

The staple crop is rice, which in 1903-4 occupied 860 square miles, or 25 per cent, of the total area under cultivation. This is of two main kinds : white paddy, which is irrigated and transplanted ; and black paddy, which grows with the help of rain alone. The latter is found only in two or three Districts besides Kistna, and is largely exported to Jaffna. Cholam {Sorghum vulgare), which occupied 590 square miles in 1903-4, is the principal ' dry ' cereal crop, and next in importance is cambu (Pennisetum typhoideum). Of industrial crops, cotton, which is chiefly produced in Palnad and Sattanapalle, occupied 377 square miles. The area under indigo has fallen from 180 square miles in 1896-7 to 40 square miles in 1903-4, the decline being attributable to the competition of the synthetic dye. Tobacco, which is largely exported to Burma, was grown on 28,000 acres. Castor occupied 39,000 acres, but the cultivation and trade in this product are gradually falling off.

During the period of thirty-one years from 1872-3 to 1903-4, an increase of 12 per cent, occurred in the total extent of holdings. The most noticeable advance was in the 'wet' cultivation, the extent of which has more than doubled ; the increase in ' dry ' hold- ings was comparatively small. In point of quality, cultivation has probably receded rather than improved since the introduction of irrigation from the Kistna. The delta ryot finds that he can grow a crop sufficient for his needs with little trouble, and ploughing is done in a perfunctory fashion, while weeding is not necessary under the transplantation system. Little advantage has been taken of the Land Improvement Loans Act, the amount advanced in sixteen years ending 1903-4 being only Rs. 28,000. Most of this was, as usual, spent in digging or repairing wells.

The large extent of pasture in the upland regions affords exceptional facilities for rearing stock. Excellent cattle of the Nellore breed are found in the Palnad, Narasaraopet, and Vinukonda taluks. These animals, though very powerful and useful for heavy draught, are slow, and deteriorate quickly if called on to work where the grass is not as good as in their native places. In the delta the want of fodder is severely felt, and the cattle are generally of poor quality. Sheep are fairly plentiful. They have, as a rule, short, coarse, red or brown hair, and are extremely leggy.

The total area irrigated in the District is 777 square miles, as shown in the table given above. Practically the whole of it is in the delta taluks of Tenali, Gudivada, Bapatla, and Bandar, where it depends upon the Kistna river. Nearly 90 per cent, of the irrigated area is supplied from Government canals, only 7 per cent, from tanks, and only '•.. per cent, from wells. The Kistna irrigation is led from the great dam across the river at Bezwada, which is 3,714 feet long and about jo feet above the bed of the stream. It was finished in 1854, and feeds the ten main canals which irrigate the delta and branch off into smaller and smaller channels until they cover every part of it. Vast as is the quantity of water utilized by this great system, a large amount of flood-water still runs to waste over the dam ; but, as the river is not filled by the rains of the north-east monsoon, there is little water in it at the end of the year, and the area that grows two crops is therefore so small as to be negligible. A project to form an enormous reservoir higher up the river, where it runs between very steep, high banks, has accordingly been investigated ; this would not only supplement the supply at the dam at Bezwada, but would also command large areas in the upland taluks above that dam. It is estimated that by this means the irrigable area might be doubled. Even under existing conditions the value of the irrigated crops is estimated at 215 lakhs annually, the greater part of this representing the value of the rice crop.

Among minor irrigation works may be mentioned a dam built across the Muneru at Polampalli, by which 3,400 acres were watered in 1903-4. A dam has also been constructed across the Palleru at Katchavaram in the Nizam's Dominions, which is at present held on lease by private individuals. All the area supplied from it, which is not very great, lies within British territory. In the uplands irrigation is from tanks, but none of them is of any great size and the total area commanded is inconsiderable. A scheme to irrigate 50,000 acres in the Divi Island in the delta by steam pumping has recently been started.

There is now very little real forest within the limits of the District, although the hills in the Palnad and those to the north-west of Vinu- konda are said to have once been covered with trees. The ' reserved ' forests cover about 1,000 square miles, of which more than a third is in the Palnad, and much of the remainder in Vinukonda and Sattanapalle. The most notable species are Pterocarpus, Terminalia, Anogeissus, and Lagerstroemia. Casuarina has been planted by private enterprise on considerable areas of the sandy wastes along the coast. On the Kondapalli hills is found a light wood known as ponuku (Gyrocarpus Jacquini), which is used in the manufacture of the well-known Konda- palli toys. In 1903-4 the forest receipts amounted to Rs. 1,49,000, and the working expenses, inclusive of establishment charges, to Rs. 74,000.

Except building stones, among which the marble used in the Amaravati stupa deserves special mention, the District contains few minerals of economic value. Iron occurs in small quantities and was formerly smelted by native methods ; and copper used to be found in Vinukonda. The most interesting mining operations which have been conducted were those in search of diamonds, before the country came into British hands. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the Sultans of Golconda ruled over Kistna, this mining was carried on extensively at Malavalli and Gollapalli in the Nuzvld country, at Kollur in Sattanapalle, and at Partiala west of Kondapalli. The first two of these mines were still being worked in 1795 wnen Dr. Heyne visited the spot. The earliest trustworthy account of the industry is that of Tavernier, the French jeweller, who visited the Kollur mines in the seventeenth century. He says that 60,000 men were at work in them ; and this would account for the ruins of extensive habitations which are still to be seen on what is now a most desolate spot. He speaks of a great diamond 900 carats in weight being found there and sent to the emperor Aurangzeb. This gem is supposed by some authors to be the famous Koh-i-niir. The Pitt, or Regent, diamond (now among the French crown jewels) is said in one account to have been found at Partiala, but Governor Pitt always kept the history of this stone a close secret.

Trade and communications

Kistna is of importance from an agricultural rather than an industrial point of view, and the arts and manufactures in it are few. All over the District the weaving of coarse cloth from the Ira e an WO ol of sheep and goats is carried on, but the market for the product is purely local. Tape for cots is made in the Palnad and Vinukonda taluks. Rough carpets are manu- factured at Vinukonda, and mats at Ainavolu. In former years fine carpets were exported to England from Masulipatam. The price charged by the exporters ranged from Rs. 8 to Rs. 10 per square yard. The industry has now fallen into decay, the few carpets that are made being of very poor quality. A tannery in the town employs about fifty hands and sends out skins to the value of about Rs. 50,000 a year, while in a rice mill some twenty to thirty persons are engaged. The silk-weaving industry of Jaggayyapeta was once flourishing, but has fallen off in late years, trade now following the line of the Nizam's Railway. The weavers (who number about fifty families) obtain raw silk from Mysore and dye it themselves. An inferior description of cloth for women's saris is largely exported to Ellore and surrounding towns.

At Bezwada the Public Works department workshops employ a daily average of about 180 hands, the maximum rising to 300. At Guntur there are three steam cotton-presses and two hand presses, each employing from twenty-five to thirty hands. A fourth steam press is about to be erected. Five cotton-ginning factories in the town employ about 150 persons, and there are seven ginning factories in other parts of the District. At Kondapalli, toys are largely manufactured from a specially light wood (Gyrocarpus Jacquini) found on the hills. Paper used to be made at Kondavid, but the industry has practically died out since 1857, when the Government offices ceased to use the paper.

Kistna possesses two seaports, Masulipatam and Nizampatam. The latter is unimportant, and the trade of the former has declined since the opening of the railway from Hyderabad to Bombay made that city the port for the Nizam's Dominions. The completion of through railway connexion between Madras and Calcutta was a further blow ; nor has Masulipatam ever fully recovered from the effects of the great inundation of 1864. The sanctioned railway from Bezwada to Masuli- patam may revive its trade to some extent ; but the port cannot be called a good one, large ships being unable to approach within five miles of the shore. In 1903-4 its exports were valued at Rs. 11,85,000 and its imports at Rs. 7,57,000. A large proportion both of the export and the import trade was with foreign countries. Of the former, goods to the value of Rs. 8,17,000 (mainly rice) were sent thither; and of the latter, merchandise valued at Rs. 5,48,000 came from that source, the largest item being European piece-goods.

Cotton is the main export from the District by rail. In 1 900-1 the presses at Guntur sent 19,000 bales (of 400 lb. each) of cotton to Cocanada and Madras, of a value ranging from Rs. 66 to Rs. 48 per 250 lb. In the following year 29,000 bales were dispatched, but the highest price obtainable was Rs. 50 and the lowest Rs. 44^. The largest total of any year during the period 1 882-1 902 was that of 1899- 1900, when 39,000 bales were sent out ; and the smallest that of 1886-7, namely, 17,408 bales. This cotton consists of two grades, known in the market as fair red and machine-ginned red Cocanada. It is especially suitable for manufacture into dyed fabrics, its natural colour taking the dye more easily than the white variety. In addition to its use for weaving, it finds a market for making string, &c.

In 1901 the East Coast Railway carried from Bezwada 27,500 tons of rice, principally to Madras city and stations along the Madras and South Indian Railways. Bezwada does a large trade in hides and skins, the sales of which amount at times to a thousand per day. Practically all of these are first roughly dressed with salt and then sent to Madras. Other exports of the District are castor-seeds, chillies, and tobacco ; and among imports are jaggery (coarse sugar), refined sugar and spirits from the Samalkot distillery, piece-goods from Madras, and kerosene oil from the same city and from Cocanada. The chief mercantile caste are the Komatis, but the skin trade of Bezwada is carried on, as elsewhere, by the Labbais, a mixed race of Musalmans.

The most important railway in the District is the East Coast line of the Madras Railway (standard gauge), which enters it from Nellore at its southern corner at Chinna Ganjam, runs through it in a north- easterly direction for 93^ miles, and then passes on into Godavari. The section from Nellore to Kistna Canal junction was opened in 1897, that on to Bezwada in 1898, and that from Bezwada to Kovvur in 1893. It crosses the Kistna river just below the anicut on a girder- bridge of twelve spans of 300 feet each. Bezwada is also the terminus of the Nizam's Guaranteed State Railway and of the Southern Mahratta Railway. The former line, which was opened in 1889, crosses the District frontier at Gangineni, 2\\ miles from Bezwada. It is also on the standard gauge. The section of the Southern Mahratta Railway (metre gauge) from Cumbum to Tadepalli was opened in 1889, and that from Tadepalli to Bezwada in 1894. The length of the line within the District is 79 miles. A line is under construction from Bezwada to Masulipatam ; and other lines have been projected from Guntur to Repalle via Tenali, and from Phirangipuram on the Southern Mahratta Railway to Guruzala, by way of Sattanapalle.

The length of the metalled roads is 709 miles, and of unmetalled roads 449 miles. With the exception of 22 miles of the latter, which are under the charge of the Public Works department, all are main- tained by the local boards. There are avenues of trees along 694 miles. On the eastern side of the Kistna river the two chief roads are that from Masulipatam to the Hyderabad frontier via Bezwada and Nandi- gama, and that from Masulipatam to Nuzvid via Gudivada ; and these are connected by various branches, partly metalled and partly not. On the western side of the river there are five principal lines, chief of which is the great northern road which runs from Sitanagaram to Madras via Guntur and Chilkalurpet. The southern portion of this part of the District, including portions of the Tenali and Bapatla taluks, is badly in need of metalled roads, and attempts are being made to remedy this defect.

Famine

Since the District came under British administration only one serious famine has been recorded, in 1833. This affected other areas also, but is known as the Guntur famine in consequence of its severity in the old Guntur District, which formerly occupied the south of Kistna District. There 150,000 persons were estimated to have died from want, and the loss of revenue was very great in 1833 and the succeeding years. In the great famine ot 1876-8 Kistna suffered but little in comparison with tracts farther south. The average number of persons on relief was only about 5,000. Including remissions of revenue, the distress cost the state 7^ lakhs. Since the irrigation system from the Kistna was completed, the delta has not only been free from famine itself but has supplied other Dis- tricts with its surplus grain. In the upland tract, however, severe distress may still be caused locally by the failure of the seasonal rains. In 1900 a few relief works were opened in the Vinukonda and Narasaraopet taluks, but no serious scarcity occurred.

Administration

For purposes of administration Kistna is divided into four subdivi- sions: namely, Guntur, Bezwada, Narasaraopet, and Masulipatam 1 .

1 Since the limits of the District were altered (see p. 319), the number of subdi- visions is now five— Ellore, Bezwada, Narasapur, Gudivada, and Masulipatam as shown in the several articles on them. Of these, the two former, which comprise respectively the Guntur, Bapatla, Tenali, and Sattanapalle taluks and the Bezwada, Nuzvid, Nandigama, and Tiruvur taluks, are ordinarily in the charge of Covenanted Civilians. Narasaraopet, which is made up of the Vinukonda, Narasaraopet, and Palnad taluks, is under a Deputy-Collector ; and the Masulipatam subdivision, which contains the head-quarters of the District and the residence of the Collector, and comprises the Bandar and Gudivada taluks, is also under a Deputy-Collector. There is a tahsildar at the head-quarters of each taluk with the exception of Tiruvur, where a deputy-tahsildar is posted ; and, except at Tiruvur, Vinukonda, and Nandigama, there is a stationary sub-magistrate at each of these stations. Deputy-ta/isll- dars are also stationed at Repalle, Ponnuru, Mangalagiri, Macherla, Kaikalur, Avanigedda, and Jaggayyapeta. The superior staff of the District consists of the usual officers, but in addition to the District Medical and Sanitary officer (whose head-quarters are at Masulipatam) a Civil Surgeon is stationed at Guntur. Civil justice is administered by seven District Munsifs, stationed at Tenali, Guntur, Bapatla, Narasaraopet, Gudivada, Masulipatam, and Bezwada ; a Sub-Judge at Masulipatam ; and the District Court at the same place. The District, especially the Bezwada subdivision, abounds in zamlnddris, and consequently the number of rent suits is large. House-breaking, ordinary theft, and cattle theft are the commonest offences, but Kistna is not in any way notoriously criminal. Dacoities are perhaps somewhat more numerous than in the adjoining Districts. In 1 90 1, at Jaggarlamudi in the Bapatla taluk, more than a lakh of rupees worth of property (chiefly cash) was stolen from the house of a Komati woman by a large gang of robbers. Crime is usually the work of the wandering gangs of criminal tribes, which consist chiefly of Kuravans and Lambadis. Latterly scarcity has prevailed for a number of years in Hyderabad, and this has had the effect of driving a number of bad characters from that State into British territory.

Our knowledge of the system of revenue administration followed by the Hindu rulers of the country before the Muhammadan conquest is very limited. Then, as now, there was a headman in each village to collect, and an accountant to record, the items of revenue, but how the assessments were calculated is obscure. Under the Muhammadans, who acquired the country in the sixteenth century, the revenues were at first for the most part collected and accounted for by Hindu officials, save in the case of the haveli land, or tracts in the neigh- bourhood of military posts intended for the maintenance of troops and Muhammadan officers. , When the Muhammadan rule became lax, these Hindu officials, whose posts were usually hereditary, began to call themselves zamlndars and to act as if they were independent princes, and in the course of time they compounded the revenue demand against their respective charges for a fixed sum. The Com- pany's officers, who found these zamlndars in possession when they took over the country, fell into the mistake of regarding them as holders of feudatory estates, paying a tribute to their suzerain, and furnishing troops in times of war. They left them undisturbed, and much mismanagement and oppression resulted.

In 1802, when the permanent settlement was introduced into the District, the peshkash or amount to be paid by each zamindar was fixed at two-thirds of half the gross profits of the land, this half being supposed to be the share paid them by the cultivators. The haveli land was divided into estates, which were sold and similarly brought under the permanent settlement. The Palnad taluk, which, as has been mentioned above, was not acquired till later, was treated differently, the villages being rented out for terms of years until 1820, when this system gave place to a partial ryotwari settlement.

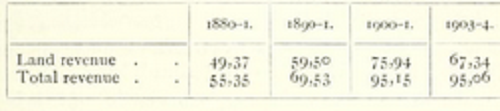

The zamindari system proved an utter failure ; extravagance and litigation on the part of the zamlndars, and in some cases the fixing of the peshkash at too high a figure, led first to the Collector being compelled to assume the management of many of the estates, and then to these being sold and bought in by Government. By 1850 the greater portion of the country was no longer under zamindari tenure. In the estates in the south of the District four different revenue systems obtained: namely, (1) ijara, or rent by auction; (2) makta, or fixed village rents ; (3) the sharing system ; and (4) a system partly makta and partly sharing. The endeavours of Government were directed towards the extension to all parts of the makta system, by which the village demand was fixed on a consideration of the average collections of former years, the ryots themselves arranging the proportion of the total demand that each should bear. The result, as might have been expected, was unsatisfactory and the country deteriorated. In 1857 the ryotwari system, which had already been adopted in Palnad, was introduced in a partial fashion for the 'dry' lands in the southern portion of the District. Between 1866 and 1874 a systematic survey and a settlement were made, and the ryotwari tenure brought into force in all Government land. The survey showed that the areas of the holdings were understated in the accounts by 7 per cent., and the settlement enhanced the revenue by 16 per cent. The settlement in the southern half of the District is now under revision. In this the 1 dry ' rates vary at present from 4 annas to Rs. 4-4 per acre, and the 'wet' rates from Rs. 1-12 to Rs. 7-8, a uniform water rate of Rs. 5 per acre being charged in addition. The average assessment here on ' dry ' land is Rs. 2 and on ' wet ' land Rs. 5 per acre. In the northern half of the District the average assessments are respectively Rs. 1-4 and Rs. 4 per acre. The revenue from land and the total revenue in recent years are given below, in thousands of rupees : —

Owing to territorial changes, the land revenue demand is now about Rs. 65,70,000.

There are three municipalities in the District : namely, Guntur and Masulipatam, both established in 1866, and Bezwada, in 1888. Out- side these towns local affairs are managed by the District board and the four taluk boards of Masulipatam, Guntur, Bezwada, and Narasaraopet, the areas in charge of which correspond with the revenue subdivisions above mentioned. The total expenditure of these bodies in 1903-4 was Rs. 7,81,000, much of which was devoted to the maintenance and construction of roads and buildings. The chief source of income is the land cess. The local affairs of twenty-five smaller towns are managed by Unions established under Act V of 1884. Ten of these Unions are within the limits of the Guntur subdivision, while Bezwada contains six, Masulipatam five, and Narasaraopet four.

The District Superintendent of police has his head-quarters at Masulipatam, and an Assistant Superintendent is stationed at Guntur. There are 84 police stations, and the number of constables is 970, working under 16 inspectors. The reserve police at Masulipatam con- sists of 85 constables and 9 head constables. The total strength of the force is 1,107. The number of talaiyaris, or rural police, is now 1,628 ; but it is proposed to reduce them to 1,478 at the forthcoming revision of the village establishments.

Kistna contains no District jail, convicts being sent to the Central jail at Rajahmundry ; but there are twenty subsidiary jails, with accom- modation for 341 prisoners.

The Census of 1901 showed that 9-2 per cent, of the males and o-'7 per cent, of the females of Kistna were able to read and write. Of the total population, 5 per cent, possessed this accomplishment, and the District takes the thirteenth place in the Presidency in the literacy of its people. Education is most widely diffused in Bandar, the head- quarters taluk, and in Guntur. The actual number of educated persons in Vinukonda and Tiruvur is small, but in proportion to the population the proportion is not lower than in the other taluks. In 1 880-1 the total number of pupils under instruction in the District was 16,5363 in 1890-1, 36,735; in 1900-1, 46,837; and in 1903-4, 54,181, of whom 10,346 were girls. On March 31, 1904, there were in the District 1,895 educational institutions, of which 1,628 were classed as public and 267 as private. Of the former, 1,586 were primary schools, secondary schools numbering 31, and training and other special schools 9. There was an Arts college at Masulipatam and another at Guntur. Nineteen schools were under the control of Government, the municipalities and the local boards managing respectively 22 and 242. Aid from public funds was granted to 817 schools, while 528 were unaided but conformed to the rules of the department. Of the boys of school-going age on March 31, 1904, 22 per cent, were receiving primary instruction; and of the girls of similar age, 6 per cent. For Musalmans alone the corresponding percentages were 42 and 12 respectively. In the same year 5,309 Pan- chama scholars were receiving instruction in 584 schools specially kept up for them. The total expenditure on education in the District in 1903-4 amounted to Rs. 3,36,000, of which Rs. 1,14,000 was derived from fees. Of the total, Rs. 2,07,000 was devoted to primary instruc- tion.

Kistna possesses 14 hospitals and 8 dispensaries. With the excep- tion of the hospitals at Bezwada, Musulipatam, and Guntur, and the dispensary for women and children at Masulipatam, which are municipal undertakings, all these institutions are supported from Local funds. Accommodation is provided for 148 in-patients, and in 1903 there were 1,793 sucn cases, the average daily number in hospital being 80. Counting both in- and out-patients, the number of persons treated was 2 5 7)494) an d the number of operations performed was 6,990. The total expenditure was Rs. 56,000, of which practically the whole was defrayed from Local and municipal funds.

In 1903-4 the number of persons successfully vaccinated was 23 per 1,000 of the population, the mean for the Presidency being 30. Vacci- nation is compulsory in the three municipalities, and has been made so in seven Unions since the beginning of 1903.

[For further particulars see the Manual of the Kistna District, by Gordon Mackenzie (1883).]

This article has been extracted from THE IMPERIAL GAZETTEER OF INDIA , 1908. OXFORD, AT THE CLARENDON PRESS. |

Note: National, provincial and district boundaries have changed considerably since 1908. Typically, old states, ‘divisions’ and districts have been broken into smaller units, and many tahsils upgraded to districts. Some units have since been renamed. Therefore, this article is being posted mainly for its historical value.