Emergency (1975-77): India

This is a collection of articles archived for the excellence of their content. Readers will be able to edit existing articles and post new articles directly |

Contents |

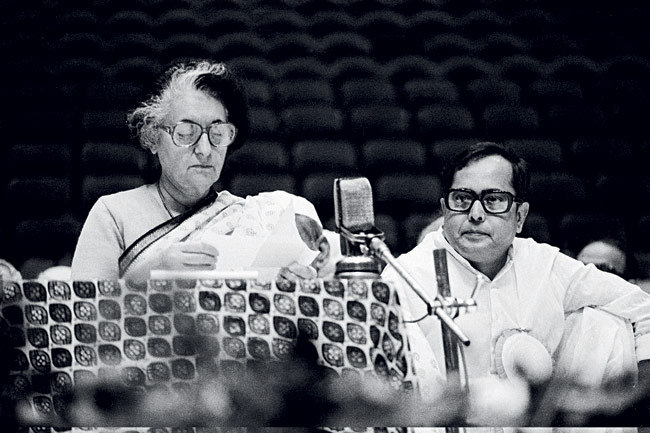

SS Ray led Indira into Emergency

Pranab Mukherjee, December 12, 2014

The 1975 Emergency was perhaps an “avoidable event” and Congress and Indira Gandhi had to pay a heavy price for this “misadventure” as suspension of fundamental rights and political activity, large scale arrests and press censorship adversely affected people, says President Pranab Mukherjee. A junior minister under Gandhi in those turbulent times, Mukherjee however, is also unsparing of the opposition then under the leadership of the late Jayaprakash Narayan, JP , whose movement appeared to him to be “directionless”. The President has penned his thoughts about the tumultuous period in India's post-independence history in his book “The Dramatic Decade: the Indira Gandhi Years” that has just been released.

He discloses that Indira Gandhi was not aware of the Constitutional provisions allowing for declaration of Emergency that was imposed in 1975 and it was Siddartha Shankar Ray who led her into the decision.

Ironically, it was Ray, then Chief Minister of West Bengal, who also took a sharp aboutturn on the authorship of the Emergency before the Shah Commission that went into `excesses' during that period and disowned that decision, according to Mukherjee.

Mukherjee, who celebrated his 79th birthday on Thursday, says,“The Dramatic Decade is the first of a trilogy; this book covers the period between 1969 and 1980...I intent to deal with the period between 1980 and 1998 in volume II, and the period between 1998 and 2012, which marked the end of my active political career, in volume III.“

“At this point in the book, it will be sufficient to say here that many of us who were part of the Union Cabinet at that time (I was a junior minister) did not then understand its deep and far reaching impact.“

Mukherjee's 321-page book covers various chapters including the liberation of Bangladesh, JP's offensive, the defeat in the 1977 elections, split in Congress and return to power in 1980 and after.

“ The Dramatic Decade: The Indira Years”: Pranab Mukherjee

Harish Khare

January 9, 2015

The partisan in Pranab Mukherjee omits crucial details about the Emergency but the politician in him offers a blue book on recouping political fortunes after a defeat.

The Dramatic Decade

The Indira Gandhi Years by Pranab Mukherjee, he has given us a fascinating history of a turbulent period in the journey of our young nation-state. Apart from two possible exceptions- L.K. Advani and Sharad Pawar-no other active political leader is well equipped as Mukherjee is to throw light on a period that saw the rise, fall and rise, again, of Indira Gandhi.

Mukherjee had been a Mr Minister for almost four decades before he became Mr President. He is a natural when it comes to exercising power and authority in the interests of the nation. Now he has given us a peep into his thoughts and calculations as he became Indira's partisan. It makes for an absorbing read.

There are, however, two glaring-and disappointing-omissions. Mukherjee has made Sanjay Gandhi, the catalyst for the political turbulence, an almost non-person; Indira's younger son's role-before, during and after the Emergency-is referred to only in passing, almost as if he were a minor figure, rather than one of the prime movers, if not the prime mover. This is at variance with all other historical accounts; it would have been useful if Mukherjee had tried to explain whether or not Sanjay's culpability was overstated by the Congress's rivals. Instead, there is a hint or two to suggest that Mukherjee was not uncomfortable with Sanjay's presence and role. There is even admiration at the spunk and spirit that Sanjay displayed in standing up to the Janata Party bullies: "It also became clear that his boys would never leave him and, in times to come, Sanjay Gandhi's boys became the cornerstone of our new movement."

A related glaring omission is the virtual absence of any discussion of the "excesses" of Emergency, which Mukherjee calls a "misadventure". For instance, he mentions that "during the Emergency, a large number of judges had been transferred to other High Courts, so much so that in one instance sixteen judges had been transferred on a single day". Yet there is no suggestion as to who had instigated it. It would have been useful to have his reflections on why these "excesses" took place. He, though, makes a loaded observation: "Interestingly, though not surprisingly, once it was declared, there was a whole host of people claiming authorship of the idea of declaring of Emergency. And, again, not surprisingly, these very people took a sharp about-turn when the Shah Commission was set up to look into the Emergency 'excesses'." Mukherjee is indeed drawing attention to a quintessential Indian democratic conundrum, which we have not yet fully confronted. There is a great yearning for a strong, vigorous executive political authority-yet without its inherent potential for over-zeal and abuse. Perhaps this has something to do with our collective gift for duplicity. Though rhetorically the country has come to abhor the Sanjay Gandhi phenomenon, it remains tantalisingly fascinated with Sanjay Gandhi-like political options.

In the context of the JP movement, Mukherjee draws attention to another democratic dilemma: "which democracy in the world would permit a change of popularly and freely elected government through means other than a popular election? Can parties beaten at the hustings replace a popularly elected government by sheer agitations?" These questions remain valid. We were confronted with a similar painful choice when the Anna Hazare platform was used to make peremptory claims in the name of the Janata.

Mukherjee's book serves another purpose. It makes us think about a slogan of which we have become very fond-the curative potency of "willpower". A student of political economy is left dissatisfied because Mukherjee does not explain why it was not possible for Indira's government-with all the requisite accruements of "willpower", a strong leader, political clarity, a decisive parliamentary majority, a cabinet full of first-class talent-to get on top of the 1973-75 economic crisis.

He does quote C. Subramaniam's 1975-76 budget speech to own up that "we have been ill-equipped to withstand" the impact of virulent global economic forces. These were pre-globalisation days. Since then national economies have become much more interdependent, though we persist in believing that a "strong leader" can solve intractable economic problems by sheer political will.

Mukherjee has alluded to some of these significant political propositions that keep on impinging upon the polity. However, the most enjoyable chunks of the book deal with the turmoil in the Congress. Throughout, Mukherjee remains an Indira loyalist, partisan and admirer.

He gives us a flavour of the 1969 split-how the polity, operated as it mostly was by the Congress bosses, had become dysfunctional and how it was Indira's historic task to initiate a series of moves that would help the "system" break out of the politically created logjam. This also created scope for institutional stand-off. The higher judiciary was not inclined to see the need for change, leave alone see any institutional role for itself in the management of that change. The result was, as Mukherjee puts it, a "strained relationship" between the executive and the judiciary-a subdued confrontation that was to later cost Indira dearly.

Mukherjee has done well to reproduce a letter Indira wrote-a few days after Pakistan's surrender at Dacca-to the chief justice of India. In a masterly formulation, she asks the chief justice to appreciate the need to look beyond the comforting stability of status quo: "... As our nation moves forward and our society gains inner cohesion and sense of direction all our great institutions, Parliament, Judiciary and Executive, will reflect the organic unity of our society.

Legal stability depends as much upon the power to look forward for necessary adjustment and adaptation as to look backward for certainty." And then she makes a telling point: "... Needs and grievances of the people in a democracy cannot be met by repression of their manifestation but by remedying the causes which underline them." Indira was riding high; the judiciary waited for her political fortunes to suffer a decline before settling a score or two with her.

When, after the 1977 defeat, the time came to choose sides, Mukherjee had no doubt or hesitation; he stood by Indira: "everybody knew of my affiliation, and I did not give them reason to believe otherwise till the day she died." No ambiguity there. And when the factional lines got redrawn, Mukherjee enjoyed the role of a factionalist: "I was then working with A.P. Sharma, C.M. Stephen, R. Gundu Rao and Vasant Sathe, and we took an active role against (D.) Barooah. We usually moved in a group and took direction from Kamalapati Tripathi and Indira Gandhi herself." As an Indira loyalist, he knew his tactics. He writes: "I knew there was no way out except to resort to a show of strength." And, again, a few pages later: "(A.R.) Antulay and I were all for the split. We were sure that the Congress could not be revived without a split." Mukherjee's account offers many clues and suggestions on how to recoup political fortunes after an electoral defeat. It is almost a blue book on how to create or take over a political party.

Indira wanted to tax farm income: 1975

From the archives of The Times of India

April 10, 2013

Indira Gandhi was willing to go where politicians today fear to tread. Back in 1975, she wanted to tax agriculture income and the rural rich. It remains a no-go area for policymakers even today. Addressing the Institute for Social and Economic Change in Bangalore, which was reported by the US mission in India, revealed by WikiLeaks, she reportedly asked the states “to overcome the compulsions that have stopped them from taxing agriculture income and the rural wealthy. She particularly deplored subsidies on water and power used for irrigation. She warned the states they would not receive any overdrafts if they overspent.” While these might sound free-market thinking, Gandhi took a different stance by saying `the "income tax department is being asked to intensify its efforts to bring self-employed professionals and traders within the tax net,’ without indicating how this was to be done.” She also warned industrial borrowers that they were being watched closely, justifying the credit squeeze on the private sector.

Fakruddin Ali Ahmed resented Indira

TIMES NEWS NETWORK

April 10, 2013

Fakruddin Ali Ahmed, the rubber stamp President during the Emergency era, may not have been a complete rubber stamp after all. According to a US embassy cable sent on August 6, 1976, the mission said, “We have heard much more reliably (than rumours) that Fakruddin is seriously concerned over the govt’s family planning moves.” The cable said the rumours have been about “some disaffection between the Prime Minister and President Fakruddin Ali Ahmed. The stories vary but have as their central core that Fakruddin is concerned that the PM and her son are pushing too hard on the political and constitutional system of India.”